If you build AI, you now have a new “silent co-founder”: the European Union AI Act.

Even if your startup is not in Europe, this law can still touch you the moment you sell to an EU customer, partner with an EU company, hire in the EU, or ship a product that lands in the EU market. And it is not a small policy memo. It is a full rulebook for how AI is built, sold, and used—based on risk. The higher the risk, the stricter the rules. (EY)

The AI Act is already “in force” (it started counting down after it was published in the EU Official Journal on July 12, 2024, and it entered into force in early August 2024). But the real obligations come in waves, on a timeline that depends on what you build. (European Parliament) For example, the EU has issued guidance for “general-purpose AI” providers, and those obligations start applying on August 2, 2025. (Digital Strategy EU)

So here is the point for startup builders: this is not “legal later.” This is “design now.”

If you wait until a big customer asks for compliance, you will pay for it with rushed rebuilds, delayed deals, and awkward investor calls. If you build with the Act in mind from day one, you get something better: cleaner product choices, faster enterprise trust, and fewer surprises when you scale.

That is also where IP becomes more than a nice-to-have. The AI Act pushes teams to document what they built, how it works, what data shaped it, how risks were tested, and how humans stay in control. Done well, that work can turn into real assets: strong technical records, clear invention lines, and a patent plan that matches the product roadmap. That is exactly what Tran.vc helps founders do—turn core AI work into defensible IP, without giving up control early. If you want help building an IP-backed foundation while you build the product, you can apply anytime: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

In this guide, I will walk you through what the EU AI Act really means in day-to-day startup life: how to quickly place your product in the right risk bucket, what “high-risk” triggers look like in real products, what changes when you ship a model vs. an app, and how to build a simple compliance habit that does not slow your team down. (Artificial Intelligence Act)

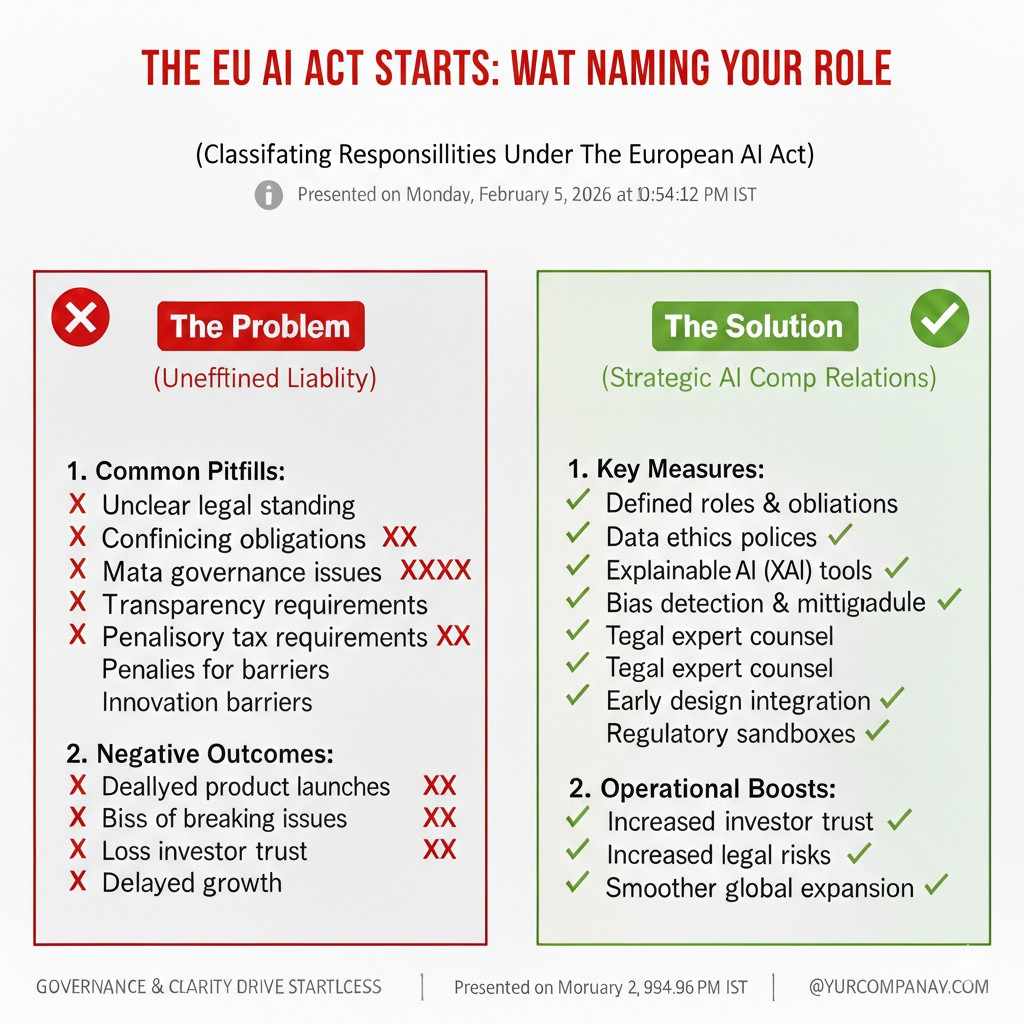

1) The EU AI Act Starts by Naming Your Role

Why your “role label” changes everything

The AI Act does not only ask, “What does the AI do?” It also asks, “What are you to this AI?” That one detail decides who must write the documents, who must test risks, who must answer regulators, and who must fix issues after launch.

Many startups lose time because they assume they are always “the builder,” so all duties land on them. In truth, your role can shift by deal, by region, and even by how your customer uses your system.

Provider: the one who puts the AI on the market

You are a provider when you develop an AI system and make it available in the EU, or when you put it into service under your name. That can mean you sell it, license it, host it, or even offer it as a free tool that supports your product.

If your startup ships an AI feature inside a SaaS app, you are usually the provider of that AI system. If your startup trains a model and offers an API, you are also acting as a provider.

The provider carries the heaviest load in the Act, because the law assumes you are closest to the design choices. You decide what data is used, what guardrails exist, what the AI is meant to do, and what it should never do.

Deployer: the one who uses the AI in real life

A deployer is the company or person who uses the AI system in a work setting. Most of your customers will be deployers. They decide where the AI is used, what inputs go in, and how outputs change decisions.

This matters because deployers get duties too, especially when the AI is high-risk. They may need to train staff, keep logs, watch for drift, and make sure humans can step in.

If you are a startup that uses someone else’s model inside your own internal process, you are acting as a deployer. That is true even if you never sell the tool.

Importer and distributor: the “middle” roles that still carry duties

An importer places an AI system from outside the EU onto the EU market. A distributor makes an AI system available in the EU supply chain without changing it much. Startups often meet these roles through partners.

If you are a US startup and your EU reseller brings your tool into Europe, that reseller may be the importer. But do not assume you are off the hook. Many contracts push compliance work back to the provider, and buyers will still ask you for proof.

Authorized representative: your EU-facing compliance anchor

If you are outside the EU but your AI is used in the EU, you may need an authorized representative. Think of this as a formal “EU mailbox” for compliance topics.

In practice, enterprise customers may ask who your representative is, because it signals seriousness. Early planning here prevents deal delays later.

How to spot your role in two minutes

If your startup controls model training, tuning, system design, release updates, and public claims about what the AI does, you are living in “provider land.” If you mainly use someone else’s AI inside your business process, you are closer to “deployer land.”

Many startups are both. You might be a provider to customers, and a deployer of a foundation model you did not train. The Act allows that reality, but you must keep the duties separate in your head and on paper.

A practical founder takeaway

Before you write a single policy, write one short internal note: “In this product, we are the provider. In this model layer, we are the deployer.” That tiny clarity saves weeks later.

This is also where good IP practice starts. If you can clearly name what you build versus what you use, you can more cleanly claim and protect what is truly yours. If you want help turning your real novelty into patents while staying lean, apply anytime: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

2) The Risk Buckets: The Act’s Real Operating System

The EU does not treat all AI the same

The AI Act is built around risk. The more the AI can harm people, the more the law asks from you. This sounds obvious, but the “harm” the EU cares about is broad.

It includes physical harm, like safety failures, but also life harm, like unfair hiring, unfair lending, loss of rights, and hidden influence. So even a “simple” model can land in a strict bucket if the setting is sensitive.

Unacceptable risk: the zone you must avoid

Some uses are treated as too harmful to allow. Startups should treat this bucket like a cliff edge, not a speed bump.

If your product idea depends on secret manipulation of users, or uses sensitive methods to control people’s behavior, you should assume you are in danger. Even if you think you have good intent, the EU may still view the use as unacceptable.

The key founder move here is to design away from this zone early. A small change in product framing or user control can shift you out of the worst category.

High-risk: the bucket that triggers serious build work

High-risk systems are allowed, but they come with strong duties. This is where many enterprise buyers will focus, because they must also comply as deployers.

High-risk is not only about the model’s power. It is also about the job the AI is doing. If your AI helps decide who gets a job, who gets a loan, who gets a benefit, who is allowed into a school, or how critical services are delivered, you are closer to high-risk.

For a startup, the big point is simple: if your AI touches someone’s life chances, plan for high-risk thinking, even if you are not fully sure yet.

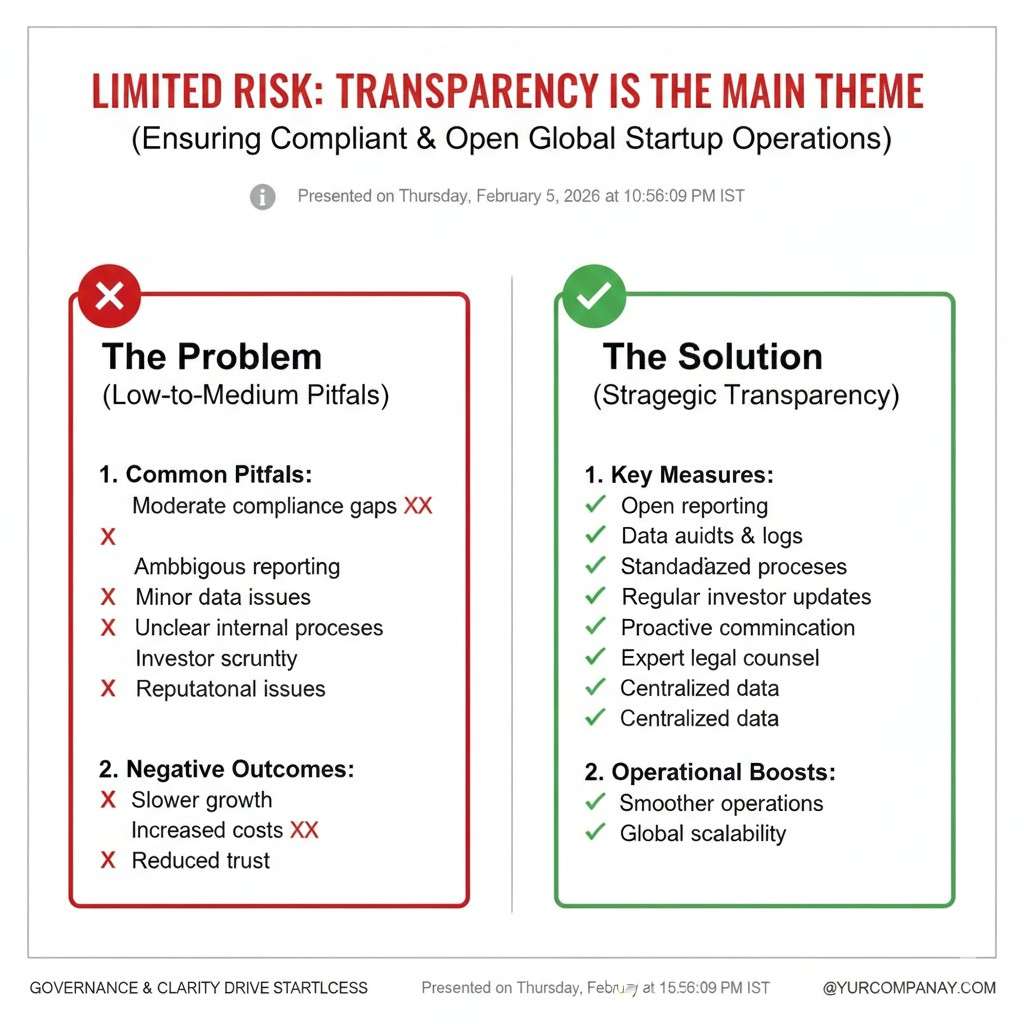

Limited risk: transparency is the main theme

This bucket is often about user awareness. If people can be misled, the law wants clear signals.

For example, if users interact with a chatbot, they may need to be told they are speaking to AI. If you generate media that looks real, you may need to label it in certain cases.

Founders sometimes shrug at this and say, “That’s easy.” It is easy when you plan for it. It becomes painful when your UI, onboarding, and logs were not designed to support it.

Minimal risk: most everyday AI tools live here

Many AI uses are not in sensitive areas and do not have strong duties under the Act. Think of common productivity tools, spam filters, and basic recommendations in low-stakes settings.

But “minimal risk” does not mean “no customer questions.” Big buyers may still request security, privacy, and safety checks. So even when the Act is light on you, your market may not be.

The trap: judging risk by model type, not by use case

Startups often say, “We only use a small model, so we are low risk.” The EU does not see it that way.

A small model used for hiring ranking can still be high-risk. A powerful model used for low-stakes grammar help may be minimal risk. The setting is the lever.

How to map your product without getting lost in law text

A practical way to think is: “If the AI gets it wrong, who pays the price?” If the answer is “a real person’s job, money, freedom, education, health, or safety,” treat it as high-risk until proven otherwise.

That mindset also helps you build a better product. When you face the risk early, you naturally add checks, better data choices, and clearer human control.

A quiet advantage for early teams

Most startups wait until a big customer forces them to do risk work. If you do a light version now, you gain speed later.

You also create strong invention material. Many patents are born from the “how” of safety, controls, and system design. Tran.vc is built for this stage: turning your real engineering work into protected assets while you build. Apply anytime: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

3) Provider vs Deployer Duties: What Each Side Must Actually Do

Why customers will ask you for “your part”

Even when your customer is the deployer, they cannot comply without you. They will ask for details only you know, like how the system was tested and what limits it has.

If you are unprepared, the deal slows down. If you have clean answers, you look mature far beyond your stage.

Provider duties: the core set you should expect

For high-risk systems, providers are expected to do serious groundwork before launch. That includes risk management steps, strong technical notes, data controls, testing, and clear instructions for use.

The spirit is simple: you should know what can go wrong, reduce the risk, and help users use it safely. The paperwork is not the point. The real point is disciplined building.

Deployer duties: the “in the field” responsibilities

Deployers must use the AI the way it was intended, monitor it, and keep humans involved when needed. They also must make sure the people using it are trained and that the AI is not used as a blind decision engine.

This is why your onboarding and admin tools matter. If you make it hard for deployers to comply, they will pick a competitor that makes it easy.

Shared duty zone: logs, transparency, and human control

Some parts are shared by nature. Logging is a good example.

If your system can log key events, it helps the deployer show oversight. If you do not support logging, the deployer cannot prove they used the system responsibly, and they may drop you.

Human control is similar. The deployer must keep humans in the loop, but you must design the product so that humans truly can step in, override, and review.

The mistake that causes late-stage rework

The biggest mistake is building AI outputs straight into automated actions, with no review path.

If your system triggers decisions without a clear review screen, clear reason display, and a “pause and check” step, you will struggle in high-risk settings. Even in lower-risk settings, this can still scare buyers.

A builder’s mental model that works

Think of the provider as the team that must prove the system is safe to sell, and the deployer as the team that must prove it was used safely.

Your job as a startup provider is to make that second proof easy. That is a product feature, not a legal chore.

Quick note before we go deeper

Next, we should talk about a category that changes the game for many startups: general-purpose AI and foundation models, because the Act treats model providers and app builders differently in important ways.

4) General-Purpose AI and Foundation Models: Where Many Startups Get Confused

Why the EU separates models from applications

The AI Act makes a clear distinction between AI systems built for a specific task and AI models built to do many things. This matters because the law assumes different levels of control and risk.

If you build an AI that only does one job, like sorting support tickets, the risk thinking is narrower. If you build a model that can be reused across many tasks, the law assumes wider impact and wider responsibility.

This is why general-purpose AI, often called foundation models, gets special treatment.

What counts as general-purpose AI

General-purpose AI is not defined by size alone. It is defined by flexibility.

If your model can be adapted to many downstream tasks, across many sectors, without retraining from scratch, it likely falls into this category. This includes many large language models, vision models, and multi-modal systems.

Even smaller teams can fall here. A startup that fine-tunes and resells a base model with broad abilities may still be considered a provider of general-purpose AI.

The key split: model provider vs system builder

The Act tries to avoid punishing small teams unfairly, so it separates duties.

If you provide the base model, you focus on model-level risks. If you build a system on top of a model, you focus on use-case risks.

But in practice, many startups do both. You might fine-tune a model and wrap it into an app. That means some duties stack.

Systemic risk: when scale changes expectations

The term “systemic risk” appears when a model is powerful enough, or widely used enough, that failures could ripple across society.

This is not only about today’s size. It is also about expected growth. If your model is designed to scale across many customers and sectors, regulators may look closer.

For founders, the practical point is this: growth plans now affect compliance plans. Scaling fast without structure can backfire.

What model-level duties look like in practice

Model providers may need to document training methods, data sources at a high level, known limits, and major risks. They may also need to test for certain harmful behaviors and explain how they reduce them.

This does not mean revealing trade secrets. The Act allows protection of confidential details. But it does mean being able to explain your design choices clearly.

This is where strong internal technical notes pay off. They serve compliance, customer trust, and future IP filings all at once.

If you build on someone else’s model

Many startups rely on third-party foundation models. That does not remove responsibility.

You still must understand the model’s limits and ensure your use does not create new risks. If you market your system as safe for a sensitive task, you own that claim.

This is why “the base model did it” is not a defense regulators or customers will accept.

A founder-friendly way to think about it

Ask yourself two questions. First, “Could my model be used in many ways I do not control?” Second, “If it fails at scale, could it harm many people at once?”

If the answer is yes, build with model-level discipline early. That discipline often becomes a moat later.

Where IP and compliance quietly overlap

Model documentation, risk analysis, and mitigation techniques often contain novel ideas. Those ideas can be patented.

Tran.vc works with founders at this exact point: helping them separate what must be disclosed from what should be protected, and turning real engineering work into long-term assets. If you want to build that way, you can apply anytime: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

5) High-Risk Systems: What “Compliance” Actually Means Day to Day

High-risk does not mean “slow” if designed right

Founders hear “high-risk” and imagine endless paperwork. In reality, most of the work is good engineering done with intention.

If you already test, log, review, and iterate, you are halfway there. The AI Act simply asks you to do this in a structured and repeatable way.