Most deep tech founders build fast. They ship code, train models, test robots, and chase real-world results. That is good. But IP moves slower than code, and the rules are strict. If you miss the right step early, you may not be able to “fix it later.” The painful part is this: many IP mistakes feel small in the moment, but they can block funding, partnerships, and even your right to sell your own product.

This article will walk through the most common IP mistakes deep tech startups make, in plain language, with clear ways to avoid each one. No fluff. Just what to do, when to do it, and how to stay safe while you move fast.

If you want help turning your inventions into real assets, you can apply anytime here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Mistake #1: Treating IP like paperwork instead of a business tool

A lot of teams think patents are a “later” problem. They see IP as forms, fees, and legal words. So they delay it until they raise. Or until the product is perfect. Or until someone copies them.

But deep tech does not work like that.

In deep tech, the invention is often inside the core. It might be your control loop, your sensor fusion, your training method, your data pipeline, your edge compute trick, your battery approach, your custom hardware stack, or your safety method. These things are not easy to see from the outside, which makes founders feel safe. They think, “No one will know how we do it.”

Then one day you hire a senior engineer from a big company, and they have seen a similar method. Or you show a demo to a customer, and their team learns enough to build around you. Or a big firm files a patent that blocks you, because you never claimed your own work.

IP is not a trophy. It is leverage.

If you raise money, a strong patent plan gives investors comfort that you have something that can last. If you sell to enterprise, IP helps with long sales cycles because buyers fear risk. If you partner with a large company, IP sets rules so you do not get squeezed. If you get copied, IP gives you a real path to stop it or negotiate.

How to avoid this mistake is simple: treat IP like product work. Not a side task.

That does not mean “file a patent for everything.” It means you choose the right inventions, then you protect them at the right time, with the right scope, and a clear reason. You also connect IP choices to business moves. For example, if your go-to-market depends on one large partnership, you protect the piece that the partner would most want to own. If your value is in training a model on rare data, you protect the method and also build trade secret controls around the data.

If you want a practical way to start, here is a clean habit: every two weeks, do a short “invention check.” Not a long meeting. Just 20 minutes. Ask: what did we build that is new, useful, and hard to copy? If the answer is “nothing,” fine. If the answer is “yes,” write one page: problem, old way, your new way, why it matters, and what makes it different. That page becomes the seed of a patent draft later.

Tran.vc does this style of work with founders. It keeps things light, but steady. And it makes IP part of how you build, not something you bolt on later. You can apply anytime: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Mistake #2: Publicly sharing the invention before you protect it

This is one of the most common mistakes, and it happens to good teams.

A founder posts a thread on X explaining their method. A team writes a blog about a new robotics pipeline. Someone gives a talk at a meetup. The deck gets shared. A demo video goes on YouTube. A paper goes on arXiv. A GitHub repo goes public. Or they apply to an accelerator and send a detailed doc to many strangers.

All of these can count as a “public disclosure.”

What is the risk? In many places outside the United States, public disclosure before filing can destroy your chance to patent that invention. In the U.S., there is a limited grace period in many cases, but you do not want to rely on it because it adds risk and limits your options later. Also, if you disclose in a messy way, it can become proof that your invention is not new, which hurts your own patent and can even help others.

Deep tech founders share because they want hiring, traction, and trust. That is normal. But the fix is also normal.

Before you share anything that teaches the “how,” file first. Even a simple provisional patent can give you a filing date. It is not perfect, but it can protect your place in line if it is written well.

Here is the part that many people miss: a weak provisional can be almost as bad as none. If the provisional does not fully describe the invention, it may not protect what you think it protects. Later, if you file the full patent, you may not get the early date for the key parts. That is why you need a good process.

A safe approach looks like this:

You plan your public moments. Product launch, talk, paper, blog, open-source release, customer demo day. For each one, you ask, “Will we reveal the method?” If yes, you file first. If no, you can share outcomes and benefits without exposing the core method.

You can still be public. You just share in the right order.

A practical example: instead of posting your full training loop, share the result, the metrics, the impact, the customer story, and the high-level idea. Then, after you file, you can share more details if you want. Some teams keep the method private even after filing, because patents require some details but not everything, and trade secrets can still matter.

If you are unsure, assume it is a disclosure and protect first. That simple rule saves many teams.

Tran.vc helps founders set this “share safely” rhythm so you can market and hire without stepping on a legal landmine. Apply anytime: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

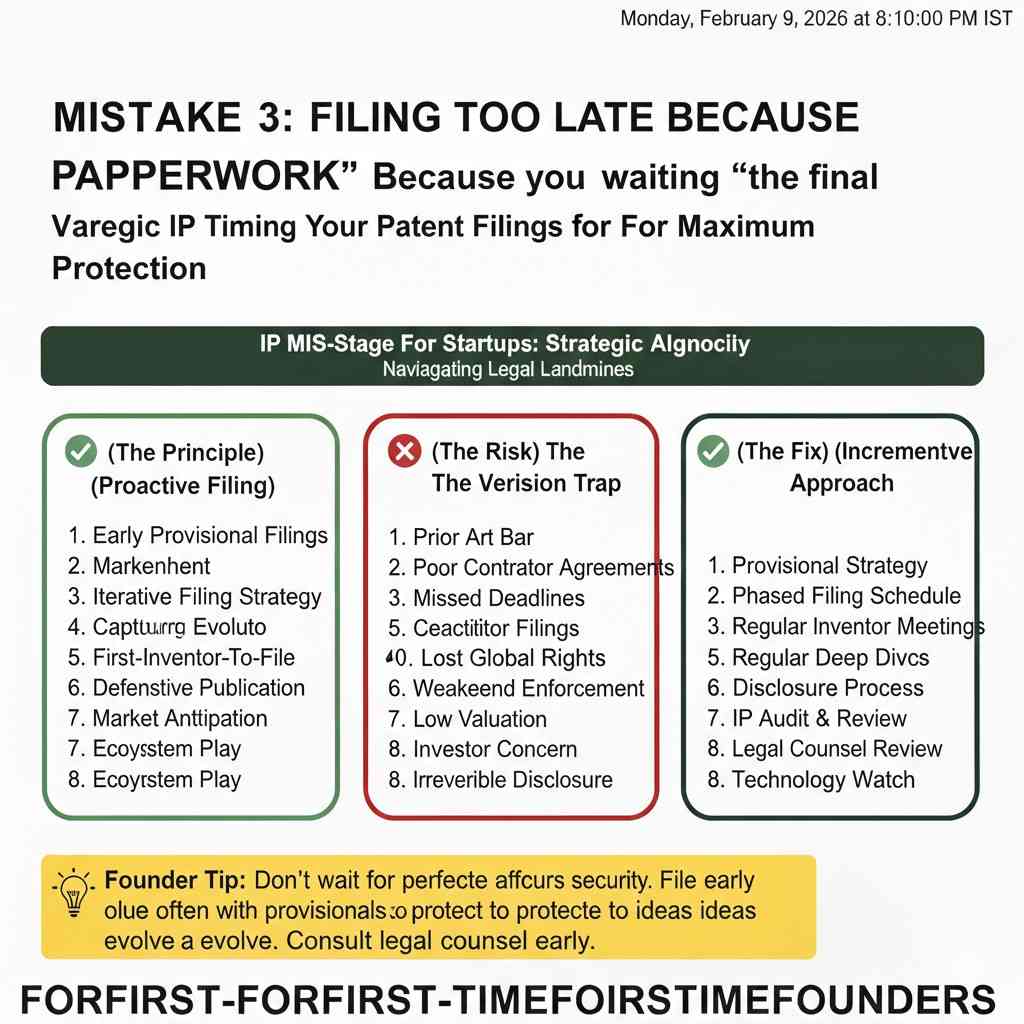

Mistake #3: Filing too late because you are waiting for “the final version”

Deep tech founders are builders. They want to perfect things before they call them “real.” They see the system evolve each week, so they think filing early is pointless.

But patents do not reward “final.” They reward “first to file” in many places and in many practical outcomes.

If you wait for perfection, two bad things can happen.

First, someone else can file around the same idea. They may not copy you. They may simply be working on the same problem. In AI, robotics, sensors, and edge compute, many teams chase the same hard problems. If they file first, you now have a wall to deal with.

Second, you might accidentally disclose before filing, as we discussed. The longer you wait, the more time you have to slip.

The better way is to file in layers.

You file when the core idea is stable enough to describe. Then you file again when you make a real step forward. This is common. It is not wasteful if done right. It builds a “fence” around your space.

Think of it like version control. Your invention has commits. Some commits are minor. Some are major. You do not patent every small commit. You patent the big ones. Early patents capture the base. Later patents capture improvements. This becomes powerful because competitors must avoid the whole chain, not just the latest version.

The key is discipline. You need a process that spots major inventive steps. Here are signs that a step is major:

You changed the method, not just the parameters.

You solved a failure mode that was blocking progress.

You got a result that others in the field struggle to get.

You made it cheaper, faster, smaller, safer, or more reliable in a way that matters.

You found a new way to use hardware or data.

When you see that, you capture it. You do not wait for the “perfect” product.

This is where founders often ask, “But will the patent become outdated?” Even if your product evolves, your early patents still matter because they cover the base idea and key paths. Also, patents can be written to cover a range of versions, not a single narrow implementation. That is why strategy matters.

Tran.vc’s approach is built for this reality: fast teams, fast iteration, and IP that keeps up. If you want that kind of support, you can apply here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Mistake #4: Filing the wrong thing because you do not know what is actually patentable

Many founders assume patents are for hardware only. Or they assume AI can’t be patented. Or they think patents must be a single “big invention,” like a new chip or a new robot arm.

That view is too narrow.

In deep tech, many patentable inventions are in the system design and methods. This can include:

How you collect data.

How you label data.

How you reduce noise.

How you fuse sensors.

How you detect failure.

How you compress models for edge use.

How you schedule tasks on limited compute.

How you handle safety checks.

How you simulate and transfer to the real world.

How you control a robot under uncertainty.

A lot of these can be patentable if they are new and useful, and if they are described well, with clear steps, and not just vague goals.

The mistake happens when founders either file nothing because they assume it is not patentable, or they file the wrong layer because they do not know what creates real protection.

For example, a team might file a patent that says, “We use machine learning to detect defects.” That is too broad and too thin at the same time. It is broad in claim, but thin in detail. It will likely be rejected or easy to design around. It also does not show the specific inventive part.

The fix is to find the “secret sauce” in a structured way.

Ask yourself: what did we do that was not obvious? What choice did we make that others would not pick right away? What small trick unlocked a big result? Where did we fight for weeks, then find a new path?

That is often the patentable part.

Then write it in a way that shows steps and structure. Not just outcomes. Patents protect how you do it, not that you got a good score.

A good way to pressure test an invention is to imagine a smart competitor. If they read your patent, could they change one step and avoid it? If yes, you need broader coverage. If they could avoid it by swapping one model type, you need to focus less on the model and more on the method around it.

Also, do not ignore the value of patenting “workflows” and “pipelines.” Many competitors can copy a model, but they cannot copy a robust system that keeps quality high in real life. Those system methods often create the moat.

Tran.vc helps founders spot the right inventions and avoid spending time on weak filings. Apply anytime: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

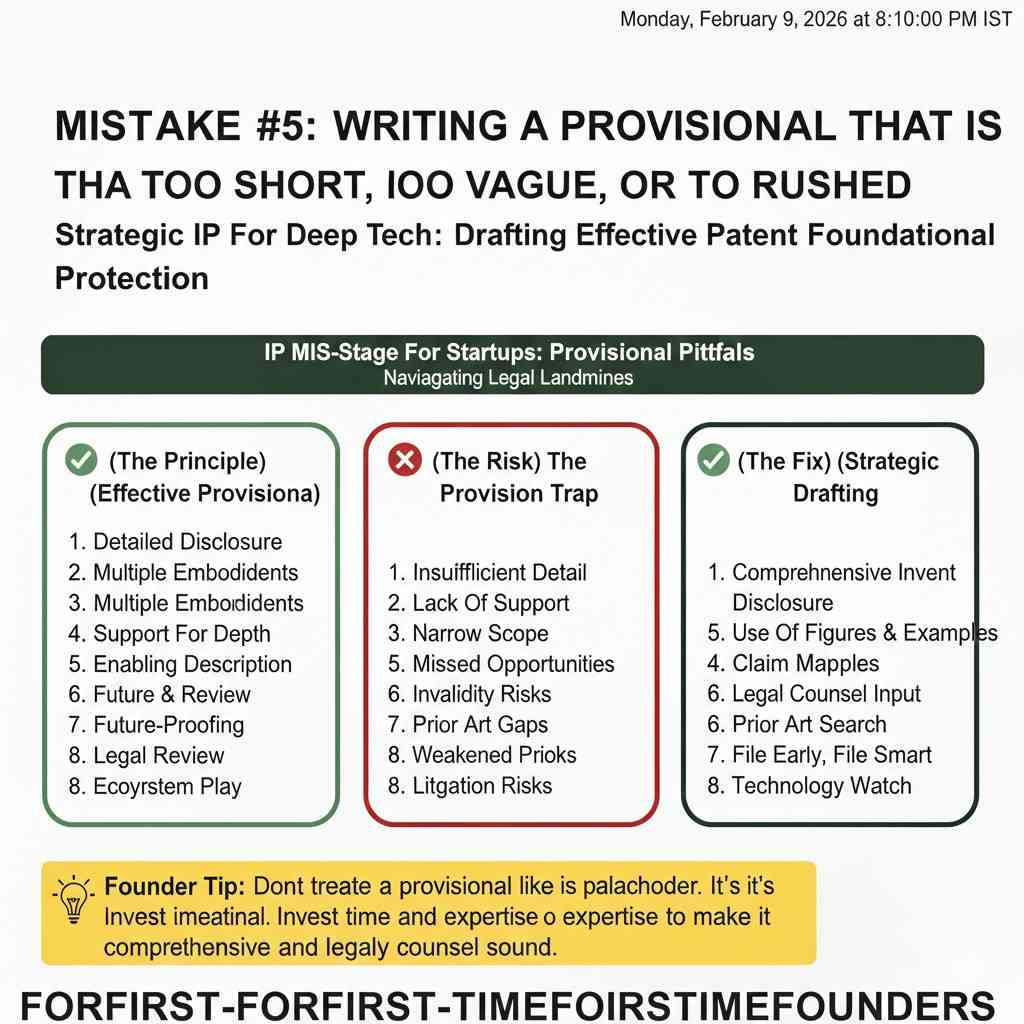

Mistake #5: Writing a provisional that is too short, too vague, or too rushed

A provisional patent sounds simple. It is often sold as a quick, cheap step. Some founders write it in one night, upload it, and feel safe.

This is risky.

A provisional is only useful if it clearly teaches the invention. If it is vague, it may not give you the early priority date you need later. And if it is missing key variations, your later patent might not be able to claim them.

The common pattern is this: a founder writes a one-page description, with a few diagrams, and files. Months later, they work with a patent attorney to file the full application. During review, it turns out the provisional did not include the key method steps, edge cases, or enough detail. Now the filing date for the real invention is later than they thought. If another filing exists in between, the startup can lose.

The fix is not “make it long.” The fix is “make it complete.”

A strong provisional does a few things well:

It explains the problem and why old ways fail.

It gives a clear system description.

It explains the method step by step.

It includes alternatives and variations.

It includes drawings or flow diagrams when helpful.

It includes examples and test cases, even simple ones.

It avoids vague words like “optimize” without saying how.

You do not need fancy writing. You need clear coverage.

If you are moving fast, you can still do this without slowing down. The trick is to build a repeatable capture method. When your engineer solves a hard problem, capture it right away with notes and diagrams. When you have to explain it to a teammate, record the explanation and turn it into a draft. The best patent drafts often come from how engineers already communicate internally.

This is also why an IP partner can help a lot. Founders should not spend their best hours formatting a legal document. They should focus on building. But the invention still needs to be captured correctly.

Tran.vc invests up to $50,000 worth of in-kind IP and patent services so founders can move fast without cutting corners. If that is useful, apply here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Mistake #6: Not knowing who owns the IP

The quiet risk inside “we’re all friends”

Many early teams start with trust. Two founders build together. A third person helps on weekends. A friend designs the first circuit. Someone from a past job gives advice and writes a bit of code. It feels natural and informal.

Later, when money shows up, the question becomes very formal: who owns what? If the answer is unclear, investors get nervous fast. They are not being picky. They know that unclear ownership can turn into lawsuits, blocked deals, or a founder leaving with key rights.

Ownership problems also show up when contractors build important parts. If your contract does not clearly assign the work to your company, the contractor may legally own it, even if you paid them.

What investors and buyers look for

When a buyer or investor does diligence, they want to see clean proof that the company owns the IP. They expect signed invention assignment agreements for founders, employees, and contractors. They also look for proof that old employers do not have a claim.

If you used code from a past job, used a lab’s equipment under their rules, or built part of the invention while still employed, those facts can create a claim. Sometimes the claim is strong. Sometimes it is weak. The issue is that it creates uncertainty, and uncertainty kills deals.

How to avoid it without slowing down

Make ownership a first-week habit, not a “later” fix. Every founder should sign an invention assignment to the company. Every employee and contractor should sign it before they start work. If someone already did work, get the paper signed now, with clear wording that covers past work too.

If you are coming from a university or a prior company, review your old agreements. Many people sign clauses without reading them. A simple legal check early can save months of pain later.

If you want help cleaning this up fast and correctly, Tran.vc can guide the process as part of its in-kind IP support. You can apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Mistake #7: Using open source in a way that hurts your product later

Open source is powerful, but rules still apply

Deep tech startups love open source because it helps you move quickly. That is a smart choice in many cases. But open source is not “free of rules.” Each license is a contract with conditions.

The mistake is not using open source. The mistake is using it without tracking what you used, which license it had, and what that license requires when you ship.

Where this becomes a real problem

Some licenses are permissive and flexible. Others can require you to share your own source code if you distribute software that links or combines with the open-source part in certain ways. This can be a big issue for startups selling enterprise products, edge devices, or robotics systems.

Even when you are not forced to open your source, messy open-source use can block partnerships. Large companies often have strict compliance rules. If you cannot show a clean bill of materials and license plan, procurement can slow down or stop.

How to stay safe while still moving fast

Start simple: maintain a running list of third-party code and licenses. This can be a lightweight file in your repo, updated each sprint. Make it someone’s job to keep it current, even if that person rotates.

Also, separate your core secret parts from common open-source tools. If the core of your advantage depends on code that must be shared later, that is a strategic risk. It might still be fine, but it must be a choice, not an accident.

A practical habit is to add a “license check” step before major releases, customer pilots, or hardware shipments. It does not have to be heavy. It just has to exist.

If you want help setting up a clean IP and compliance workflow that founders can actually follow, apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

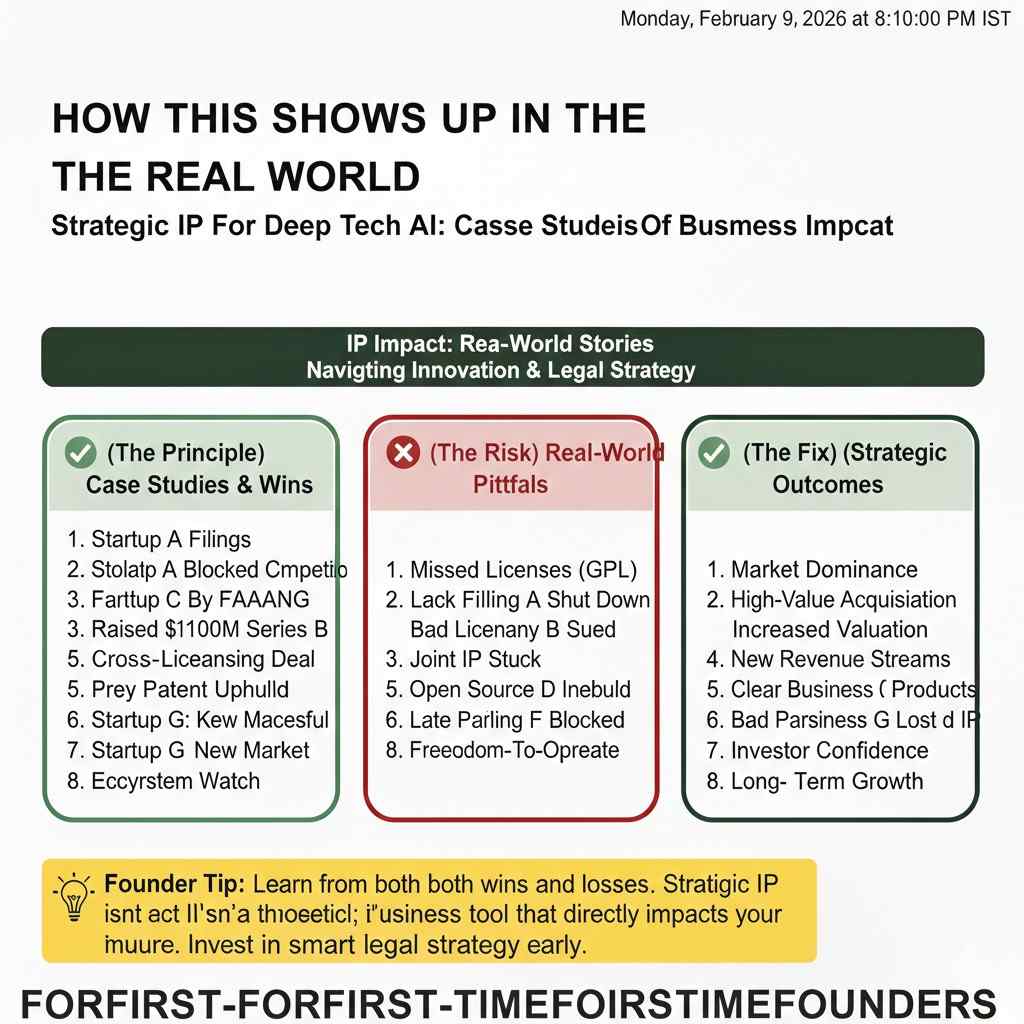

Mistake #8: Filing patents that do not match your business goals

Patents should protect a plan, not a wish

A common trap is filing patents that sound impressive but do not protect what your company needs to win. Some teams file whatever feels “patentable” instead of what creates leverage.

For example, a robotics startup might patent a minor mechanical change while the real advantage is in the control system. Or an AI company might file around a model choice while the real moat is their data method and deployment system.

A patent is not just a document. It is a fence around value. If the fence is built in the wrong place, it does not matter how strong it is.

How this shows up in the real world

This mistake appears later when you pitch investors. They ask what your patents cover. You explain it, and they do not see how it blocks a competitor. You end up with “patents” on paper but not real protection in practice.

It also shows up when a partner asks for certain rights. If your IP does not cover the area the partner cares about, you are weak in that negotiation. You may be forced to accept bad terms or lose the deal.

A better way to decide what to protect

Start with your threat model. Who might copy you? A big company? Another startup? A supplier? A customer building in-house? Each threat pushes you toward different IP choices.

Then map your value chain. Where does value appear? Is it at data capture, training, deployment, hardware design, safety, or integration? Protect the step where you create value and the step where others would try to remove you.

This is why good IP strategy feels like business strategy. When they match, your patents support your pricing, your partnerships, and your fundraising story.

Tran.vc works with founders to align IP with the real go-to-market path so filings become leverage, not noise. You can apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Mistake #9: Being too specific and easy to design around

Narrow patents feel safe, but they can be weak

Technical founders often write in a very exact way. They describe the one architecture they used, the one sensor stack they chose, or the one model family that worked.

If your patent ends up being that narrow, a competitor can often change one part and avoid it. They can keep the same business value while stepping around your claims.

This does not mean you should write vague patents. It means you should capture the concept and also the variations that keep the concept alive.

The “one switch” problem

Imagine your patent says you use camera plus lidar in a certain pipeline. A competitor uses camera plus radar. If your patent only covers lidar, you might lose the ability to stop them, even if the core idea is the same.

Or imagine your patent says you use a transformer model. A competitor uses a different model class but follows the same method steps around it. If your patent is tied to the model type, it is easier to avoid.

How to draft for real protection

A strong patent describes the system in layers. It explains the core steps in a way that is not tied to one brand, one model type, or one sensor only.

It also includes alternatives on purpose. If the invention works with three kinds of sensors, say so. If it works on edge or cloud, say so. If it works with different model types, say so.

This is also why drawings and flow charts help. They let you show the invention as a method, not a single implementation. That creates a wider fence while staying clear and defensible.

Tran.vc’s patent process focuses on coverage that matches how competitors actually copy, not how founders like to code. Apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Mistake #10: Thinking trade secrets and patents are the same thing

You can lose a trade secret without noticing

A trade secret is something valuable you keep private. It can be code, a dataset, a process, a tuning method, a supplier detail, or a testing approach. Trade secrets can be powerful, but only if you protect them.

The mistake is treating trade secrets like they protect themselves. They do not. If you share them widely, store them in messy ways, or allow loose access, you may lose the ability to claim they were secret.

Once a secret becomes public, it is gone. You cannot “unshare” it.