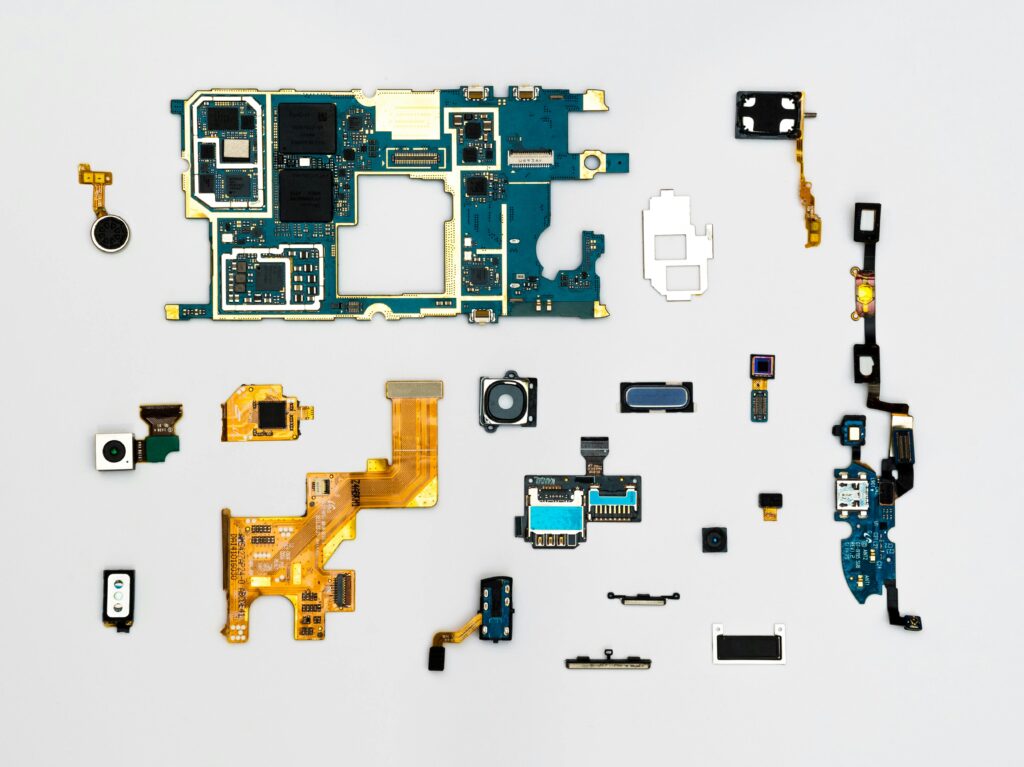

Pitching a hardware startup is a very different game from pitching a pure software or AI idea. Hardware is slower to build, more expensive to produce, and harder to scale in the early days. That means investors look at it with a sharper eye. They’re not just asking if the product works—they’re asking if it can survive the long road to market without running out of money, time, or patience.

Most founders underestimate how much this changes the pitch. They go in with the same slide deck they’d use for a SaaS company and wonder why the conversation stalls. The truth is, hardware investors are looking for different proof, different risk signals, and a much stronger moat from day one.

In this guide, we’ll break down the mistakes that quietly kill great hardware pitches—and how to avoid them. You’ll learn how to position your startup so investors see not just a cool gadget, but a defensible business they can bet on with confidence.

Why Most Hardware Startup Pitches Fail Before They Even Get to the Numbers

If you’ve ever walked out of a meeting with investors feeling like they “just didn’t get it,” there’s a good chance the problem wasn’t your product—it was the way you framed it. Hardware founders often start their pitch too far down the track. They jump into features, tech specs, or a live demo before the investor has even decided if the problem is worth solving.

This is a trap that kills momentum before it starts. In hardware, especially in robotics and AI-powered devices, investors need to be convinced of the why before they’ll care about the how. They know that building physical products is a capital-intensive grind.

They’ve seen too many founders underestimate manufacturing timelines, production costs, and distribution challenges. That means they’re automatically looking for reasons to say no unless you give them a reason to lean in from the first slide.

The first reason pitches fail is a weak problem statement. Many founders assume the product is so obviously useful that they don’t need to spell it out. But usefulness is subjective. What seems urgent to you as the inventor might not register at all with someone outside your niche.

If your startup builds a sensor that monitors soil health in real time, you might think the value is obvious. But until you show the investor how poor soil management costs farmers millions annually and how your device directly prevents that loss, they won’t feel the pain point in their gut.

Another common mistake is focusing too much on the product’s “cool factor” without proving it’s tied to a large, reachable market. Investors might smile at a clever design, but they’re not funding you because your prototype is impressive—they’re funding you because they believe it can sell at scale. This is where many hardware founders lose the room. They talk passionately about engineering breakthroughs but fail to connect them to a clear path to adoption.

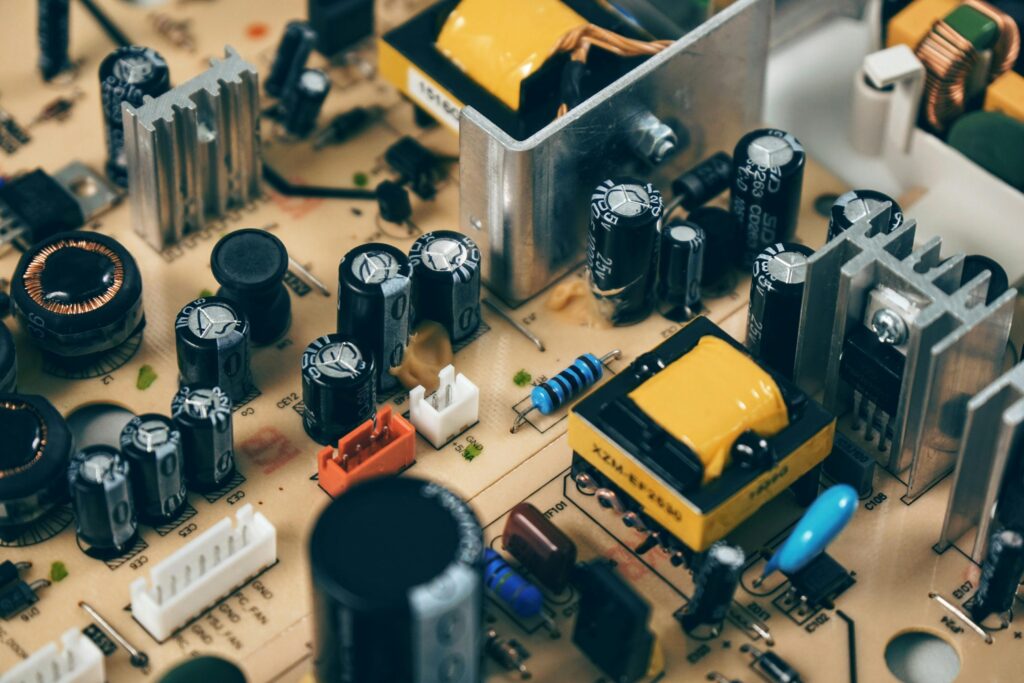

Ignoring the Hardware Reality Check

The other reason pitches fall flat early is that founders skip over the harsh realities of hardware. They either pretend the risks don’t exist or assume investors won’t notice. The truth is, investors are thinking about manufacturing complexity, supply chain fragility, and unit economics from the very beginning. If you don’t address those concerns before they bring them up, they’ll assume you either don’t know or don’t have a plan.

You don’t have to have every detail worked out, but you do need to show you’ve thought about it. If you know that one key component is in short supply globally, acknowledge it—and then explain how you’ve secured multiple suppliers or considered alternative materials.

If your first production run will be expensive, explain why early adopters will pay a premium and how your costs will drop over time. This shows maturity. It makes you look like someone who can navigate obstacles, not just build prototypes in a lab.

One subtle but fatal mistake is underestimating timelines. Hardware founders often claim they can go from prototype to market in under a year. Most investors know that’s unlikely unless you already have manufacturing relationships and a supply chain in place. When they hear unrealistic timelines, they don’t see ambition—they see inexperience. It’s better to give a realistic roadmap and then beat it than to overpromise and underdeliver.

Failing to Protect What You’ve Built

Perhaps the most dangerous pre-pitch mistake is walking into the room without any real moat. In software, speed to market can sometimes be enough to fend off competitors. In hardware, speed alone is rarely enough. If your design, manufacturing process, or integrated AI can be copied, it will be—often by larger, better-funded companies.

Investors know this. When they hear a hardware pitch, one of the first unspoken questions is: “What stops someone else from making this?” If you can’t answer that clearly, you’ve already lost leverage. This is why intellectual property strategy is critical before you pitch. Filing patents on your unique technology, manufacturing methods, or embedded algorithms doesn’t just protect your invention—it sends a signal to investors that you understand the business of hardware.

This is also why working with an experienced partner like Tran.vc before you raise can make such a difference. Instead of walking into the pitch saying, “We have a great product,” you can walk in saying, “We have a great product, and here’s how we’ve locked down the core technology so no one else can replicate it.” That shift in positioning instantly changes the way investors evaluate you.

Not Knowing Who You’re Talking To

Even the strongest hardware idea can die in the wrong room. Many founders make the mistake of pitching to every investor they can get in front of without checking if that investor even funds hardware at their stage. Some VCs focus on capital-light software plays and avoid hardware altogether. Others invest in hardware but only at later stages when the product is already in market.

If you’re pitching an AI-powered drone to a fund that only backs enterprise SaaS, you’re wasting your shot. The investor might be polite, but they’re mentally checking out within minutes. The better approach is to do deep research on each target investor.

Know which hardware companies they’ve funded, what sectors they’re drawn to, and whether they’ve invested in similar supply chain or robotics plays.

When you tailor your pitch to fit their worldview, you stand out. You can reference their portfolio, show how your startup complements it, and even hint at potential synergies with their other investments. This makes the conversation about partnership, not just persuasion.

Letting the Story Get Lost in the Specs

One final early killer of hardware pitches is drowning the investor in technical details before they’re ready. Your engineering team might be proud of the fact that your device uses custom-milled components and a novel thermal management system, but until the investor sees how that solves a big, costly problem, those details are just noise.

Investors buy into stories first, then numbers, then specs. You need to start with a narrative they can repeat to their partners: “This startup is solving X problem for Y market with a product that Z.” If they can’t sum it up in one clear sentence after hearing your pitch, you haven’t done your job.

The technical depth comes later, once they’re already hooked on the opportunity. That’s when they’ll want to know how your embedded AI model outperforms competitors or how your modular design cuts assembly time in half. But if you lead with those details before they care about the outcome, you’re inviting them to get lost in the weeds.

Designing a Hardware Pitch That Preempts Investor Concerns

When you pitch a hardware startup, you’re not just showing off a product—you’re presenting a business that requires capital, infrastructure, and time before it pays back. Investors know this, and they walk into the meeting with a checklist of worries. If you can answer those concerns before they voice them, you change the tone of the conversation. Instead of playing defense, you’re in control.

The best pitches are built like bridges: they lead the investor from curiosity to conviction without giving them a chance to fall into doubt. This happens when every part of your story is anchored in proof, foresight, and clarity.

Starting with the Problem, Not the Product

Most founders begin their pitch by introducing their product. In hardware, this is often a mistake. You need to start with the problem—because that’s what sets the stakes. If the investor doesn’t believe the problem is urgent, they won’t care how clever your solution is.

This doesn’t mean giving a vague market statistic. It means making the problem visceral. If you’re pitching a robotics solution for warehouse automation, don’t open with a diagram of your machine. Open with a moment: a warehouse floor in peak season, workers scrambling to keep up, delays costing millions in missed orders. Let them feel the pressure that your product relieves.

Once the problem is real in their mind, you introduce your solution as the natural answer. This creates a shift—the investor is no longer evaluating your product in isolation, but in the context of a real, high-stakes challenge.

Showing That You’ve Thought Beyond the Prototype

Investors are wary of hardware founders who fall in love with their prototypes but haven’t thought through the path to market. You have to show that your product isn’t just a one-off build—it’s designed for manufacturability, scalability, and long-term viability.

This means addressing production early in your pitch. If you’ve already identified manufacturing partners, secured supplier agreements, or run small-scale production tests, bring those up. If you’ve considered alternative manufacturing methods to reduce risk, explain that too. The goal is to prove that you can take this from a lab bench to a production line without hitting fatal bottlenecks.

It also helps to show that you’ve designed with cost in mind from day one. A gorgeous prototype that costs $5,000 per unit to produce isn’t a business—it’s a hobby. Investors need to see that you’ve mapped out how costs drop over time as you scale, and that your unit economics work even before you hit massive production volumes.

Addressing Time-to-Market Without Overpromising

One of the fastest ways to lose credibility is to claim you can go from prototype to mass production in an unrealistically short time. Experienced hardware investors have seen enough delays to know that’s rarely possible. Instead of making a wild promise, show them a realistic timeline—and the steps you’ve already completed to de-risk it.

For example, you might explain that you’ve already tested component sourcing with two suppliers, you’ve completed regulatory compliance assessments, and your initial pilot customers are lined up for beta testing. This shifts the conversation from “will they get it done?” to “how fast can they move now that the foundation is set?”

When you present your timeline, anchor it in external realities. Mention lead times for critical components, time required for tooling, and the testing cycles for safety or certification. This not only shows honesty but also makes you look like a founder who knows how to manage complexity.

Proving You Own Your Edge

In hardware, a strong moat is everything. If you can’t stop competitors from making a similar product, you’ll be undercut before you can scale. Investors want to see that you’ve locked down your intellectual property before you come to them.

This is where patents, trade secrets, and exclusive agreements become central to your pitch. Don’t just say you’ve filed a patent—explain what it covers and why it matters. If your IP protects a core manufacturing method, a sensor design, or an AI model embedded in your device, make that crystal clear. The goal is to leave the investor thinking, “Even if someone else tries to enter this market, they can’t do it without running into their IP wall.”

If you’re working with an experienced IP partner like Tran.vc, mention that early. It signals that your IP strategy is not an afterthought—it’s part of your growth plan. This instantly reduces perceived risk.

Making the Market Feel Reachable

Investors are wary of “big market” claims that aren’t grounded in reality. If you say your product addresses a $100 billion global market, you need to show the slice you can actually capture first—and how you’ll expand from there.

The best way to make the market feel reachable is to start small and concrete. For example, if your hardware solves a logistics problem, you might target mid-sized regional warehouses in the first 18 months, prove ROI, and then expand to national players. This shows that you’ve thought about adoption in stages, not as one giant leap.

Backing this up with early traction is even better. Pilot programs, letters of intent, and signed contracts give investors something real to hang onto. Even if revenue is small, it’s proof that someone outside your team believes in the product enough to commit.

Showing the Path to Scaling Without Losing Quality

Scaling hardware is a balancing act. Move too fast, and quality slips. Move too slow, and competitors catch up. Investors want to see that you’ve thought about how to maintain quality while increasing volume.

This could mean automating parts of your assembly process, building relationships with multiple manufacturing partners, or setting up in regions with favorable logistics and labor conditions. Whatever your approach, the key is to make it clear that quality control is built into your plan from the start.

When you talk about scaling, include the team you’ll need to make it happen. If you’re the technical founder, show that you know when and how you’ll bring in operations, manufacturing, and sales leadership. This reassures investors that you’re not planning to do everything yourself.

Closing the Loop Before They Can Open It

Every investor comes into a hardware pitch with a mental list of risks. If you can address those risks before they voice them, you flip the dynamic. Instead of them probing for weaknesses, they’re nodding along because you’ve shown you’ve already thought through the hard parts.

By the time you finish, they should feel like most of their questions have been answered without them asking. They’re left with curiosity, not doubt. That’s when you’ve won the room—not by dazzling them with a flashy demo, but by giving them the rare feeling that you are a founder who has already solved half the problems they were worried about.

Mastering the Investor Q&A and Follow-Up Stage

No matter how polished your pitch is, the real test comes when you stop talking and the investor starts asking questions. This is where deals are often won or lost—not because of the answers themselves, but because of how the founder handles the moment. In hardware, where the stakes are higher and the risks are more obvious, Q&A can quickly shift from friendly curiosity to a stress test.

If you want to keep momentum after the pitch, you have to treat this stage as part of the pitch itself, not an afterthought. Every answer is another chance to build trust, show competence, and reinforce that your startup is worth betting on.

Staying Calm When the Hard Questions Hit

The most common mistake founders make in Q&A is treating tough questions as an attack. Investors will ask about your weakest points—that’s their job. If they didn’t care, they wouldn’t bother digging deeper. Getting defensive or rushing through your answer tells them you’re not prepared for the realities of scaling hardware.

When an investor questions your cost assumptions, manufacturing timelines, or IP strategy, take a breath before you respond. A short pause shows control. Then, answer with facts and reasoning, not emotion. If you’ve run multiple cost models or supply chain scenarios, explain them. If you’ve had to adjust timelines based on component lead times, be transparent about it. This signals maturity and realism, qualities investors prize.

Owning the Unknowns Without Losing Authority

You will not have every answer. The difference between a credible founder and an overconfident one is how they handle those gaps. Pretending you know something when you don’t will backfire—hardware investors are often industry veterans who can spot a bluff instantly.

If you don’t know the answer, acknowledge it and commit to following up quickly. A line like, “I don’t have that figure on hand, but I can send you the detailed breakdown by tomorrow,” keeps you in control while showing you’re willing to do the work. When you follow through promptly, you reinforce your reliability.

Anticipating Their Concerns Before They Voice Them

One of the most effective ways to handle Q&A is to predict what will be asked and prepare short, confident responses ahead of time. In hardware pitches, there are a few themes that almost always come up: manufacturing risk, IP defensibility, regulatory hurdles, time-to-market, and customer acquisition costs.

If you can answer those before they even ask, you create the impression that you’ve already been through these conversations with others and emerged stronger. This can be as simple as saying during the pitch, “I know one question that often comes up is about our component supply chain—here’s how we’ve de-risked it.” When they hear you anticipate their thoughts, they start to view you as a peer, not a rookie.

Keeping the Dialogue Strategic

A good Q&A isn’t just about answering—it’s about steering the conversation toward your strengths. If they ask about production costs, answer, but then link it back to your unique cost advantages. If they challenge your market size, acknowledge their concern and use it as a bridge to your go-to-market plan.

The key is to avoid letting the conversation drift into minutiae that don’t drive the investment decision. Hardware is full of technical details, but not all of them are relevant at this stage. Keep pulling the discussion back to why this is a valuable, defensible, and timely opportunity.

Following Up With Purpose, Not Persistence

Once the meeting ends, the clock starts ticking. You want to stay top of mind without becoming noise. The best follow-up is prompt, concise, and directly tied to the conversation you just had.

If they asked for more data, send it within 24 hours. If they wanted to see a prototype in action, schedule that demo right away. If you mentioned a pilot customer, follow up with a short case study showing results. Each touchpoint should feel like you’re adding value, not just “checking in.”

This is where many founders misstep. They either disappear for weeks or flood the investor with minor updates. You want to hit the sweet spot—present enough progress to keep excitement alive, but hold back enough that each update feels meaningful.

Using Momentum to Pull Others In

In many hardware deals, one interested investor isn’t enough. You often need a lead investor to commit before others follow. The post-pitch period is the time to use momentum strategically. If you get strong signals from one investor, you can (carefully) let others know you’re in advanced talks. This creates urgency and positions your round as something they might miss out on.

When done right, this can flip the dynamic—investors start competing for space in your round instead of you chasing them. But it only works if you’re credible, responsive, and consistently showing progress.

Knowing When to Push and When to Let It Breathe

Some deals move fast, others take months. Part of post-pitch success is knowing when to push for a decision and when to give space. If an investor is clearly engaged but needs more proof, focus on delivering that proof rather than forcing an artificial deadline. If they’re stalling without clear reasons, it may be time to redirect your energy toward more serious prospects.

The key is to never let momentum die completely. Even a short update—like securing a new pilot, hitting a production milestone, or filing a new patent—can reignite interest weeks after a meeting.

Building a Hardware Startup Investors See as Inevitable

The most fundable hardware startups don’t start building their pitch the week before a meeting. They’ve been preparing for months—sometimes years—without realizing it. By the time they sit down with an investor, they already look like a company on a trajectory that’s hard to stop.

When investors sense inevitability, the dynamic changes. They stop asking, “Will this work?” and start asking, “How can I be part of this?” Getting to that point requires work in three key areas: credibility, defensibility, and momentum.

Establishing Credibility Before You’re in the Room

Hardware is expensive, slow to iterate, and full of risks. Because of that, investors are selective about which founders they trust with capital. You can’t earn that trust in a single pitch—it has to be built through signals that accumulate over time.

One of the strongest credibility signals is alignment between your background and your product. If you’re building an autonomous agricultural machine and you’ve spent the last decade in precision farming technology, that’s not just relevant—it’s compelling. It tells investors you understand the market from the inside, not as an outsider guessing at the problems.

Another credibility signal is validation from others. This could be early customers, industry awards, or advisors with strong reputations. Even before revenue, a letter of intent from a respected buyer can shift how investors see you. It proves that someone with real decision-making power believes in what you’re building.

You also want to ensure that every public touchpoint tells a consistent story. Your website, LinkedIn, and any media coverage should all present the same clear, concise positioning. Confusion kills confidence. A founder who controls their narrative earns more trust before they ever open a pitch deck.

Locking Down Your Moat Early

In hardware, intellectual property is your armor. Without it, even the best product can be replicated by someone with deeper pockets and faster distribution. Too many founders treat patents as something to think about after they raise funding. By then, it may be too late.

The smartest hardware founders work on their IP strategy alongside their product development. This doesn’t just mean filing a patent—it means understanding which parts of your system create real defensibility and protecting them first. It could be a novel sensor design, a unique manufacturing process, or the AI integration that makes your device smarter than competitors’.

If you can walk into a pitch saying, “Our technology is protected under X patents and covers the following critical functions,” you’re already ahead of most early-stage hardware founders. It changes the tone of the conversation. Now the investor isn’t just evaluating a product—they’re looking at an asset that can’t be easily duplicated.

Partners like Tran.vc are built for this stage. They help founders identify their most valuable IP and turn it into something enforceable and investment-ready—before you’ve even raised your seed round. This preparation means you don’t just look protected; you actually are.

Showing Momentum Without Overstretching

Momentum is one of the most powerful psychological triggers in fundraising. When investors see a company that’s already moving—shipping prototypes, signing pilots, hitting milestones—they feel urgency to join before the window closes.

For hardware founders, building momentum without burning through resources is tricky. This is where smart staging comes in. Instead of trying to tackle full production out of the gate, you run tightly scoped pilots with early adopters. You choose customers who will give you strong feedback and potentially act as reference accounts later.

Document everything. If your device reduced downtime for a customer by 30%, put it in writing. If your pilot user renewed their contract or ordered more units, make that part of your narrative. Each small win builds the perception that you’re progressing toward something inevitable.

Momentum isn’t just about customers—it’s also about product development milestones. Completing your design freeze, securing a key supplier, or passing a safety certification are all moments worth sharing. They show that you’re methodically removing risks from the business, which is exactly what investors want to see.

Designing for Scalability from the Start

Investors think in terms of scale. A beautiful prototype is interesting, but what excites them is a system that can produce thousands of units reliably. If you haven’t built with scale in mind from the start, you may have to rebuild later at great expense.

Designing for scalability means thinking about manufacturing efficiency, modular components, and assembly simplicity even in the prototype stage. It also means considering serviceability—how easy it will be to repair or upgrade units in the field. Products that require costly, complex maintenance drain margins and slow adoption.

If you can explain in your pitch how your design decisions now will make scaling easier later, you’re speaking directly to investor priorities. You’re showing that you understand the full lifecycle of the business, not just the first chapter.

Laying the Groundwork for a Smooth Go-to-Market

Many hardware founders underestimate how hard it is to get from finished product to widespread adoption. Even if the tech is ready, the market may need education, distribution channels may need to be built, and customers may need financing options.

The earlier you start building those pathways, the stronger your pitch will be. This could mean securing early distribution agreements, partnering with industry groups, or exploring leasing models to lower the barrier for customers.

By the time you pitch, you want to be able to say, “We already have our first sales channels lined up, and here’s how we’ll expand from there.” This shifts the investor’s focus from if you can sell to how fast you can grow.

Positioning Yourself as the Founder They Want to Back

At the end of the day, investors fund people as much as products. They want to believe that you can handle the grind of building a hardware company—the delays, the unexpected costs, the constant problem-solving.

This means showing resilience in your story. If you’ve already overcome a major production setback, talk about it. If you pivoted your design after discovering a better approach, explain how you made that call. These moments demonstrate adaptability, which is a non-negotiable trait in hardware founders.

When you combine credibility, defensibility, momentum, scalability, and resilience, you create something rare: a hardware startup that feels inevitable. That’s the point where investors stop needing to be convinced and start figuring out how to get involved.

Conclusion

Pitching a hardware startup is not just about showing a working product. It’s about proving you can take that product through the long, complex journey to market—and defend it once you get there.

When you walk into a meeting with clear credibility, a locked-down moat, real momentum, and a design built for scale, you shift the conversation. Investors stop asking if you can make it work and start asking how they can be part of it. That’s when funding becomes less of a hurdle and more of a natural next step.

Too many hardware founders wait until after they raise money to protect their IP, secure manufacturing pathways, or validate their market. By then, they’ve lost months—and sometimes their edge.

If you’re ready to make your startup feel inevitable to investors, Tran.vc can help you get there. We invest up to $50,000 in in-kind IP and patent services so you pitch from a position of strength, not hope.

Apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/.