Double taxation sounds like a boring tax phrase. But for founders, it can quietly drain cash, slow hiring, and even scare off investors if it shows up at the wrong time.

In the simplest sense, “double taxation” means the same money gets taxed two times. Not because you made a mistake, but because of how your company is set up and how money moves from the business to a person.

Here’s the part most first-time founders miss: double taxation is not just a “C-Corp problem” or a “later-stage problem.” It can pop up early, especially when you start paying yourself, issuing equity, raising money, selling services, or doing cross-border work. And once you trip into it, it can be annoying to unwind.

So in this guide, I’m going to explain double taxation in plain words, with founder-style examples. No heavy tax language. No “law school” tone. Just what you need to understand so you can make clean choices.

Also, quick note: Tran.vc backs technical founders with up to $50,000 in in-kind IP and patent services, so you can protect what you’re building early and raise with more leverage. If you want help building a real moat, you can apply anytime here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

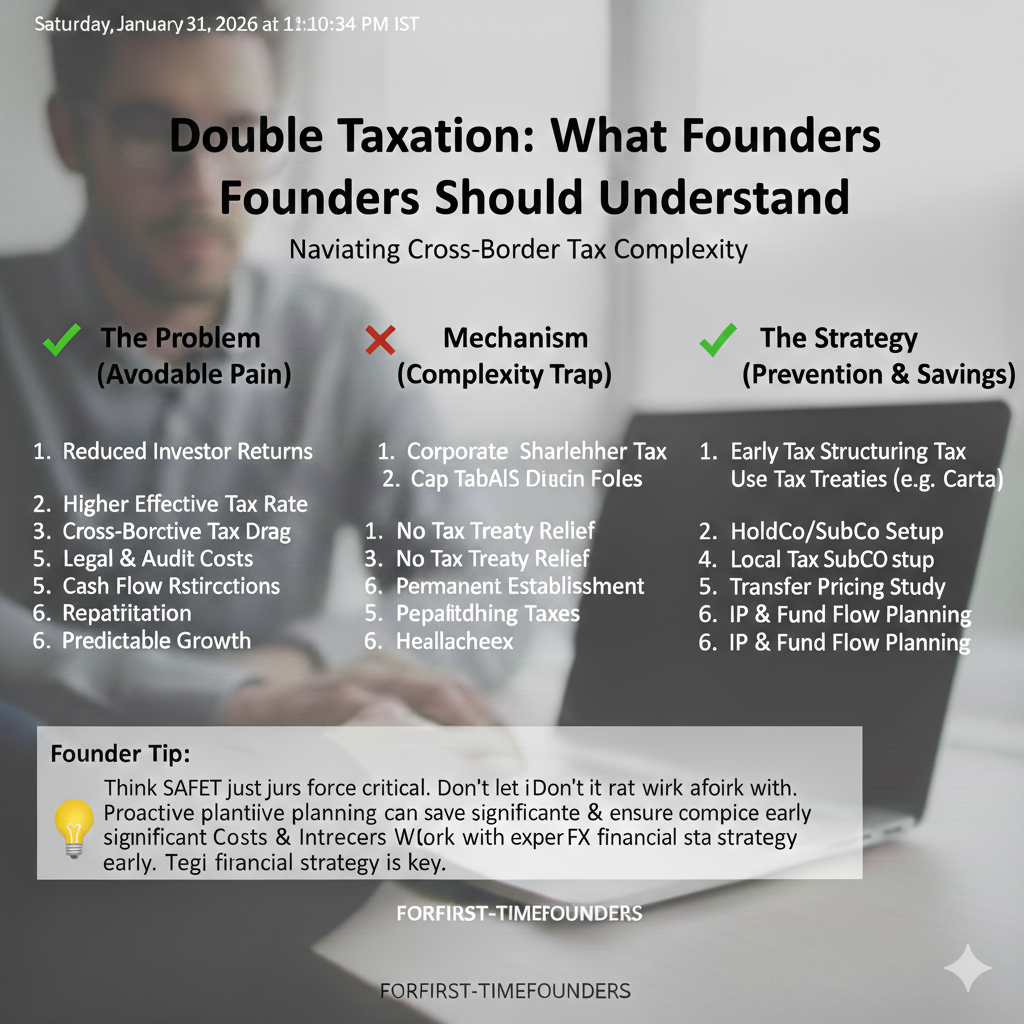

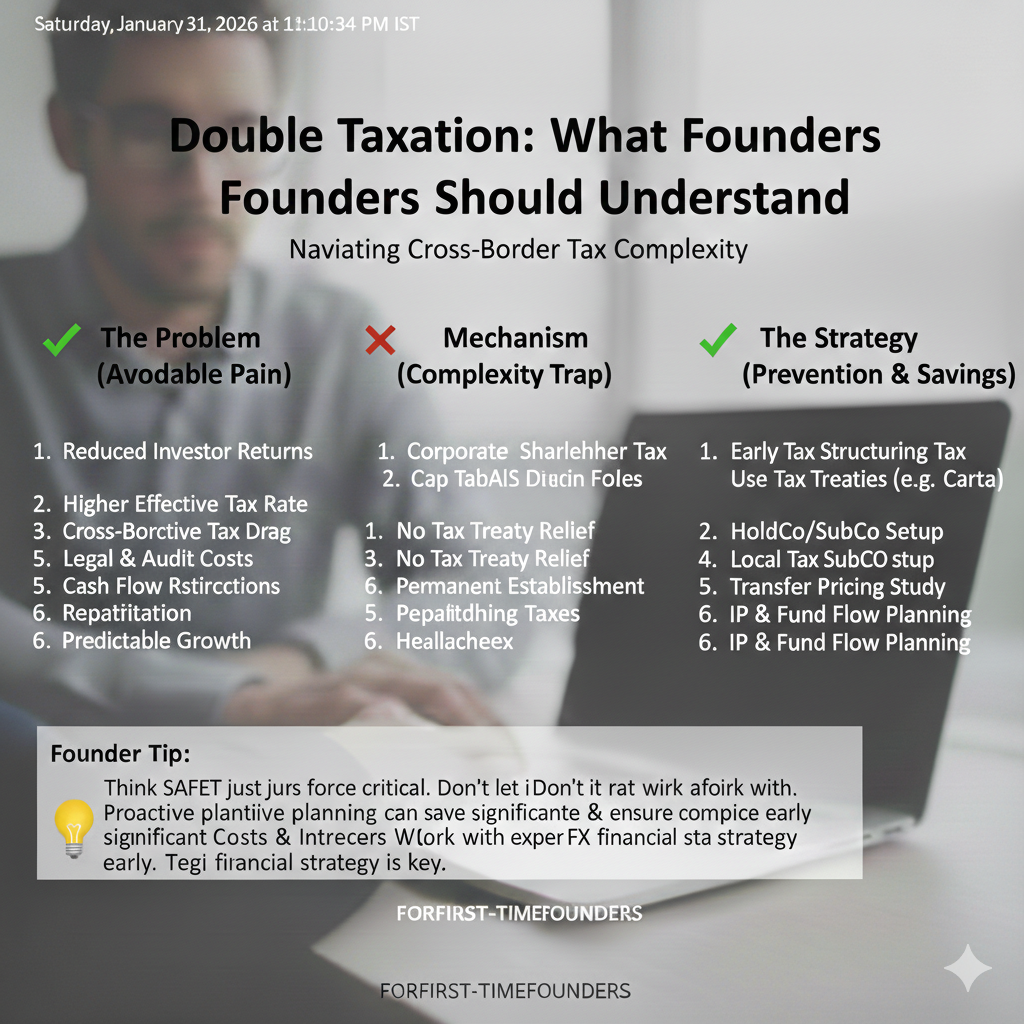

Double Taxation: What Founders Should Understand

Why this topic matters more than you think

Double taxation sounds like a tax term that only shows up once you are “big.” That is not true. It can hit early, right when you start paying yourself, signing contracts, or planning your first fundraise.

Most founders do not get in trouble because they are careless. They get in trouble because tax rules do not match how founders think. You think in products, users, and runway. Taxes think in entities, flows of money, and timing.

When you understand double taxation, you can avoid surprise bills. You can also explain your setup clearly to investors, which builds trust and reduces friction during diligence.

If you are building deep tech, AI, or robotics, you are also building valuable know-how. Tran.vc helps founders protect that know-how with up to $50,000 in in-kind patent and IP services. If you want to build leverage early, you can apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

What “double taxation” actually means

One pool of money, taxed twice

At its core, double taxation means the same earnings are taxed two times at two different levels. First, the company pays tax on its profit. Then, the owner pays tax again when that profit is paid out to them.

This is why founders often hear, “C-Corps get double taxed.” That statement is common, but it is also incomplete. The deeper idea is about where the tax happens and when the money changes hands.

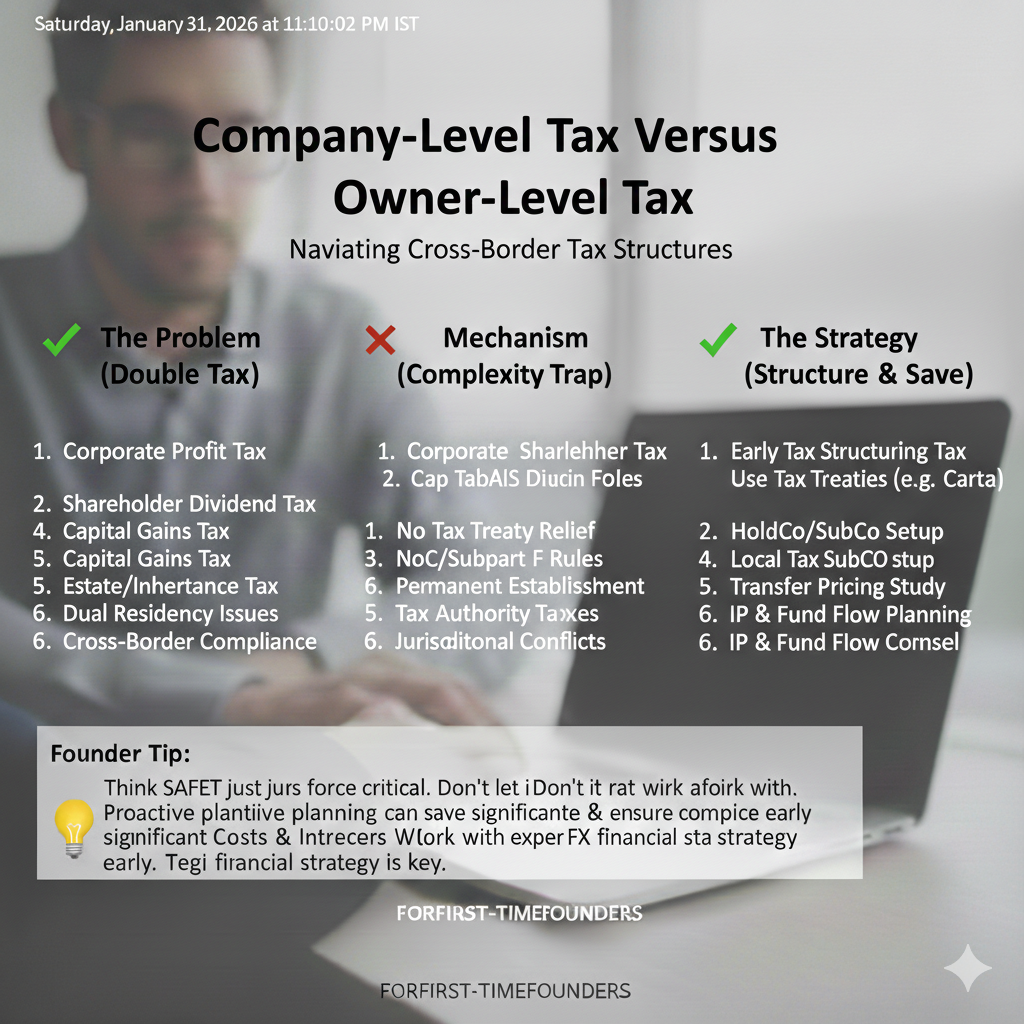

Company-level tax versus owner-level tax

Think of your company as one legal person and you as another legal person. Tax rules treat those “people” as separate. When your company earns income, it may owe tax on that income.

Later, when the company sends money to you in certain ways, the IRS may treat that payment as income to you. That is a second tax event, even if the cash originally came from the same business profit.

Why founders confuse this early

Founders often say, “But it’s my company, so it’s my money.” Emotionally, that makes sense. Legally, it does not work that way for many structures.

Once you form a company, you create separation. That separation is useful, because it can protect you from liability. But it also creates rules about how money moves, and those rules are where double taxation can appear.

The most common place founders see double taxation

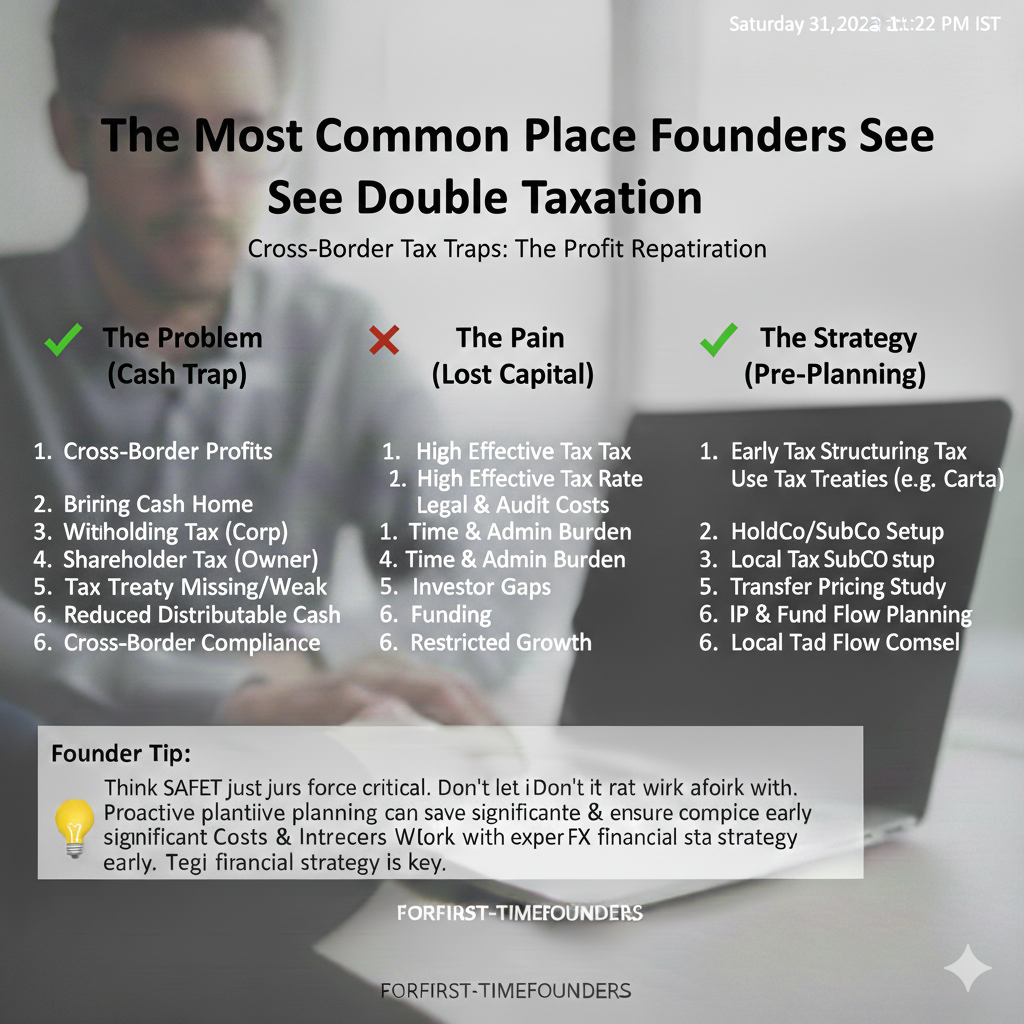

The classic C-Corp profit to dividend path

A C-Corporation is its own taxpayer. If the company makes profit, the company may owe corporate income tax on that profit.

If the company then distributes that profit to shareholders as a dividend, shareholders may owe tax on that dividend. This is the classic “taxed at the company, then taxed again when paid to owners” situation.

Why dividends are not the only trigger

Founders hear “dividends” and think, “We will never pay dividends. We will reinvest.” That is often true early.

But cash can leave the company in other ways. Some of those ways are treated like dividends by tax rules, even if you never call them dividends. That is where founders get surprised.

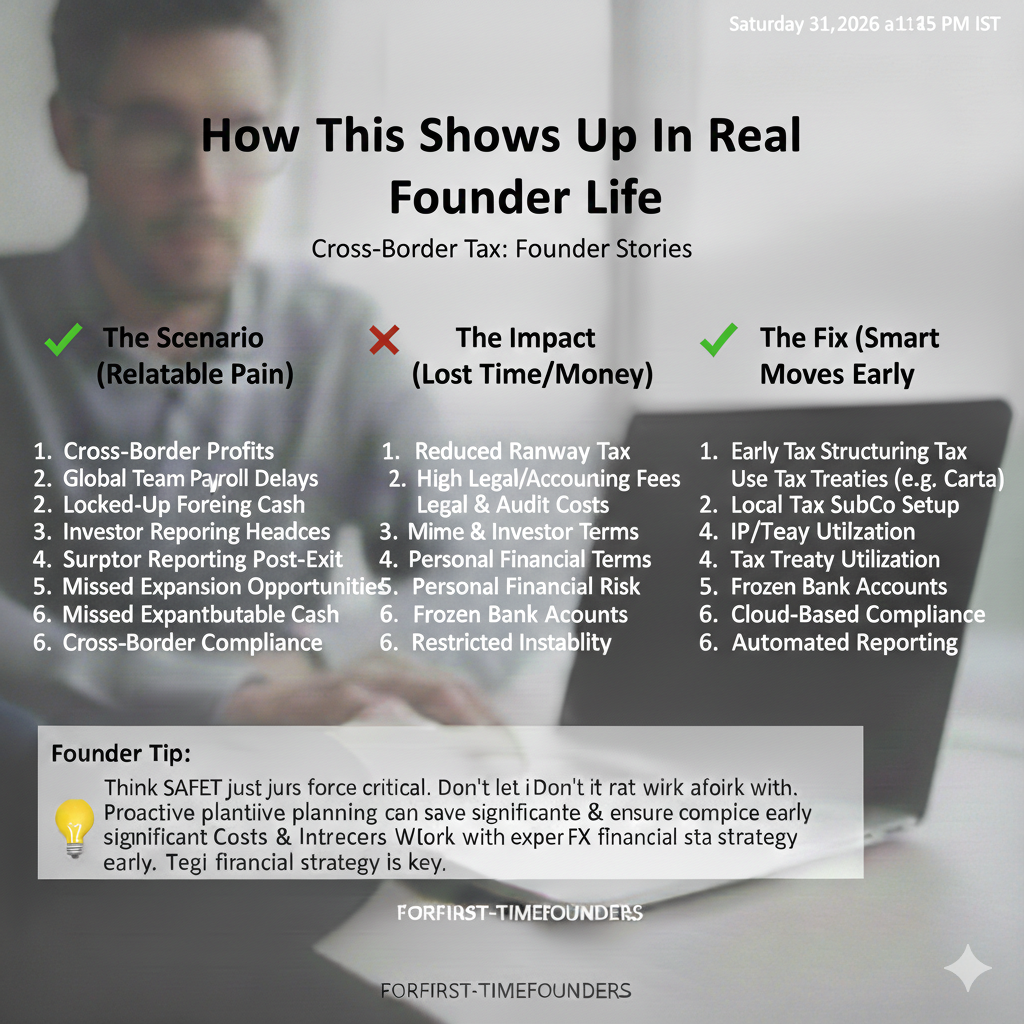

How this shows up in real founder life

Here is a common story. A founder builds revenue. The company has money. The founder wants to take some cash out, so they simply transfer it to their personal account.

If the company is a C-Corp, that transfer is not automatically “fine.” If it is not payroll, and not a documented loan, and not a real expense reimbursement, it can be treated as a distribution. That can create tax at the personal level, even if the company already paid tax on the profit.

The structures that change the double taxation story

C-Corp: the most common venture-backed structure

Most venture-backed startups in the U.S. are Delaware C-Corps. Investors like them for many reasons, including how stock works, how option plans work, and how future financing rounds are handled.

The tradeoff is that the company is taxed separately. So founders must be careful about how they take money out, and how they plan for future exits.

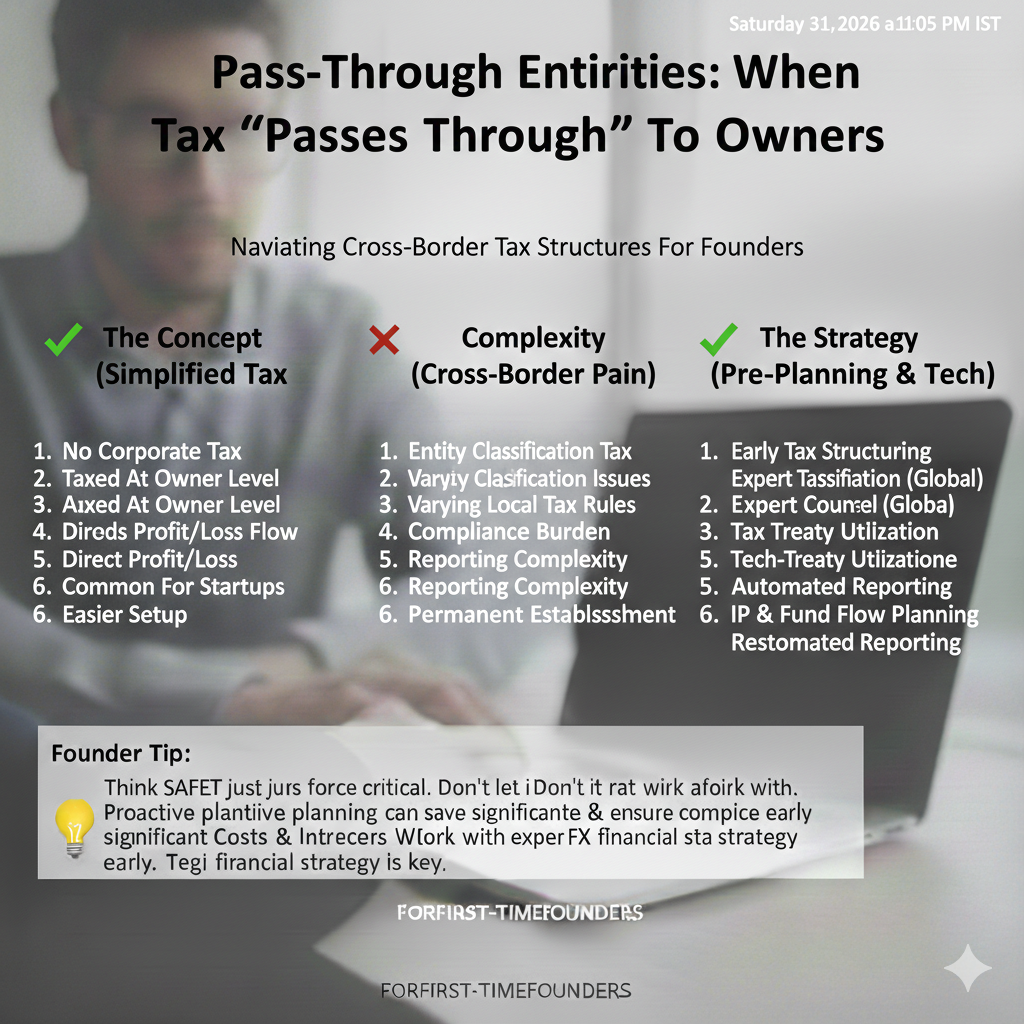

Pass-through entities: when tax “passes through” to owners

In many pass-through structures, the company itself does not pay federal income tax in the same way. Instead, profits “pass through” and are reported on the owners’ personal tax returns.

This changes the double taxation picture. You may not get taxed at the company level, but you can still face tax in ways that feel like “double,” especially when you pay yourself and also owe tax on profits you did not even receive in cash.

Why founders should not choose a structure based only on taxes

Tax is important, but it is not the only factor. Fundraising plans, equity plans, IP ownership, and how clean your cap table is can matter more.

For deep tech founders, there is another critical layer: protecting inventions and building a real moat. Tran.vc focuses on that foundation. If you want help turning your work into defensible IP, apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Double taxation can exist even without dividends

Salary and payroll tax is not “double taxation,” but it feels expensive

When you pay yourself a salary, the company deducts that salary as an expense. That often reduces corporate profit, which can reduce corporate tax.

But you still pay personal income tax on your salary, and there are payroll taxes too. This is not double taxation in the strict textbook sense, because the company got a deduction. Yet it still feels like a big tax bite, so founders often lump it into the same bucket.

The key is to know the difference. Salary is usually the cleanest way to pay founders in a C-Corp, as long as it is documented and reasonable.

Owner distributions that are not documented correctly

If you pull money out without payroll, without a board approval path where needed, and without proper accounting entries, you can create a second tax event.

The IRS cares about labels and documentation. If you treat a payment casually, the IRS may treat it harshly. The fix is simple but strict: use payroll, use reimbursements with receipts, or use properly documented loans with real terms.

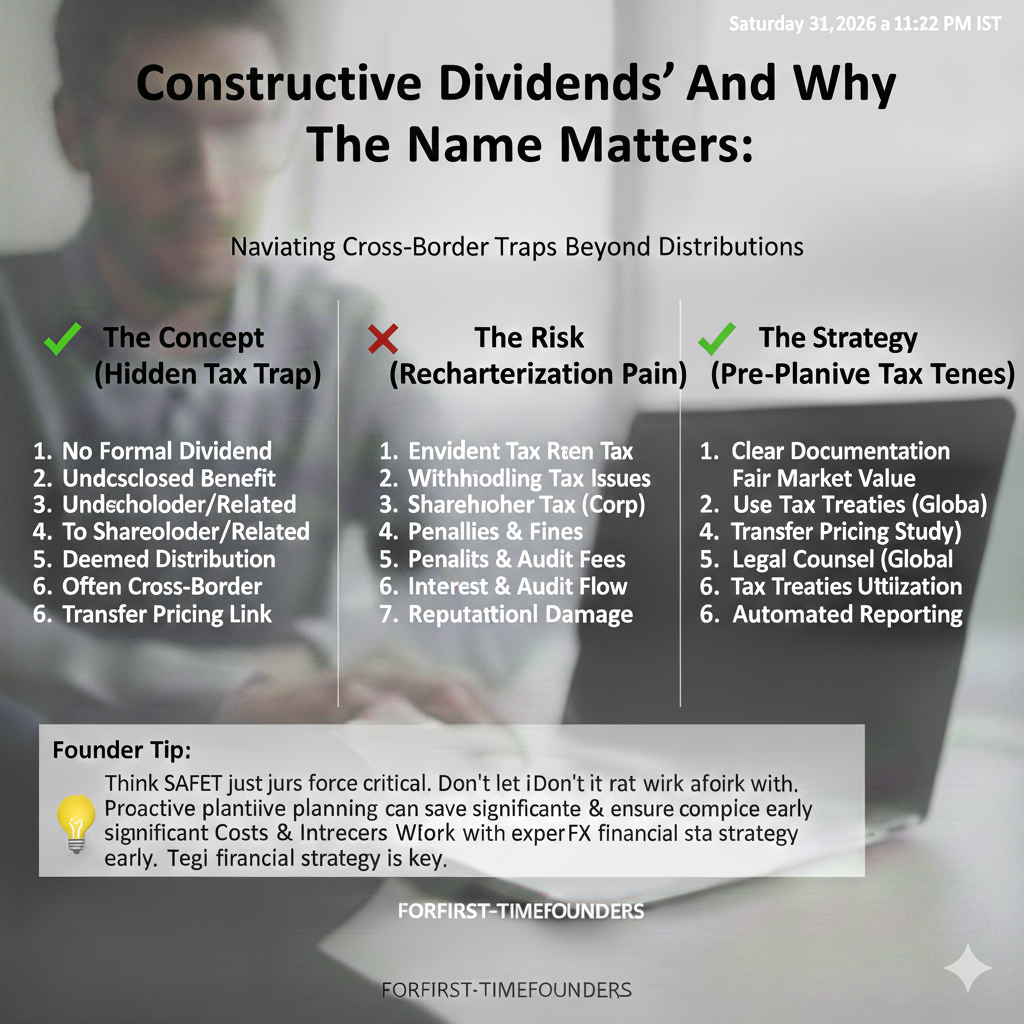

“Constructive dividends” and why the name matters

A constructive dividend is a situation where the company benefits you personally, and tax rules treat that benefit like a dividend.

This can happen when the company pays personal expenses, or gives you use of company assets in a way that is not properly treated as compensation. Founders often do this innocently, especially when cash is tight and boundaries blur.

The safer approach is to set clear policies early. Treat the company like a real company, even when it is just you and a laptop.

How double taxation affects fundraising and exits

Investors care about clean structure and clean flows

Investors do not want tax surprises. They also do not want messy books that create risk during diligence.

If your company has unclear payments to founders, unclear loans, or unclear reimbursements, it can slow down a round. It can also lead to legal cleanup costs, which is time you do not have when you are trying to close.

Exits: where double taxation can become very real

When founders dream, they dream about the exit. But the tax treatment of that exit depends on many things: whether it is a stock sale or asset sale, how the company is structured, and how earnings and IP are held.

In a C-Corp, certain exit paths can result in taxes at the corporate level and then again when proceeds are distributed to shareholders. That can materially change what you take home.

This is one reason it is smart to think ahead early. You do not need to predict your exit. You just need to avoid structures that trap you later.

IP ownership and exit value

For deep tech, IP is often the heart of the value. If IP ownership is messy, it can impact deal terms. It can also impact tax outcomes if assets need to be moved around close to an exit.

Tran.vc helps founders build clean, defensible IP early so that later conversations are easier. If you want to protect what you are building and reduce future friction, apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Where founders accidentally create double taxation

Taking money out “because it’s there”

Startups are stressful, and founders are human. When cash hits the account after a few good months, it is tempting to treat it like a personal cushion.

But business cash needs a clean path to become personal cash. If you do not use a clean path, you can create tax issues and bookkeeping issues at the same time.

A strong habit is to decide, in advance, how founder pay will work. Even if the pay is low, the process should be stable and documented.

Mixing personal and business expenses

This is one of the most common early mistakes. You buy a laptop, pay a bill, book travel, or cover a personal cost with the company card because it is “easier.”

Sometimes that is fine if it is truly a business expense and you keep records. But when personal expenses slip in, the risk grows. Some personal payments can be treated as taxable benefits. Others can be treated like distributions.

The fix is not complicated, but it requires discipline. Separate cards, separate accounts, and clear reimbursements with receipts.

Cross-border founders and tax layers

If you have founders in different countries, or customers in different countries, you can face tax in more than one jurisdiction.

Double taxation can happen across borders too. One country taxes income, another country taxes the same income again. Sometimes treaties reduce this, but treaties are not automatic and paperwork matters.

If you are in this situation, treat it as a design problem. Map where the company is, where the founders are, where the work is done, and where customers pay from. Then get proper advice early instead of reacting later.

What you should do right now, even if you are pre-seed

Set up clean money movement rules

A founder does not need fancy finance systems. But you do need rules. Decide how you will pay yourselves. Decide how reimbursements work. Decide who approves expenses.

When rules are clear, accounting becomes simple. Taxes become more predictable. Investors see maturity, even if the team is tiny.

Keep your books investor-ready, not just “tax-ready”

Many early founders treat bookkeeping as a yearly tax task. That is risky.

If you treat it as an operating tool, you will catch problems early. You will also move faster during fundraising, because the story in your deck will match the story in your numbers.

Build an IP plan that supports your tax and fundraising plan

Founders often treat IP as something they do “later.” But if your company value is tied to inventions, IP is not optional. It is part of the business.

Tran.vc exists to help founders do this early without giving up control or chasing VC too soon. If you want up to $50,000 in in-kind patent and IP services to build a moat around your tech, apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Double Taxation: What Founders Should Understand

How double taxation looks different depending on your company type

When people talk about double taxation, they often talk like there is only one story. In real life, there are a few different stories, and founders get confused because the word “double” sounds like the same thing every time.

It helps to separate the idea into two buckets. One bucket is the classic “company pays tax, then owner pays tax” path. The other bucket is the “I am paying tax on money I did not really feel I received” path. Both can hurt. They just happen for different reasons.

A lot of founders only learn this after they have already picked a structure and started moving money around. The better move is to learn the patterns now, so you can design around them while it is still easy.

C-Corps: where the “two layers” are built into the design

A C-Corp is a separate taxpayer. That is the core fact that drives most of the double taxation story. If the company earns profit, the company can owe tax on that profit.

Then, if the company shares that profit with owners in the form of dividends, owners can owe tax again. That is the second layer. This is why you hear people say “C-Corps get taxed twice.”

But founders should zoom out a bit. The real decision is not only “avoid dividends.” The real decision is “be intentional about how you move value from the company to yourself.” That includes salary, bonuses, equity, loans, benefits, and reimbursements.

If you are building a venture-backed company, you will most likely be in a C-Corp anyway. So the goal is not to fear it. The goal is to use it properly.

Pass-throughs: when you can still feel “double taxed,” even without two layers

Pass-through companies, like many LLCs and S-Corps, often do not pay federal income tax in the same way as a C-Corp. Instead, the profit flows through to the owners’ tax returns.

This can sound great, but it creates a different kind of pain. You might owe personal tax on profits even if you did not take cash out. Founders sometimes call this “double taxation” because it feels like they are paying tax while also leaving cash in the business.

This is not the textbook “two layers” problem, but it is still a cash problem. It can make founders short on personal cash, especially in years when the business reinvests heavily.

The founder takeaway: choose structure for your plan, not for fear

If you are building something investors will want to fund with a priced equity round, the C-Corp path is common for a reason. It fits standard fundraising patterns, option plans, and later rounds.

If you are building a lifestyle business, a consulting firm, or a bootstrapped product with stable profit, a pass-through can make sense for tax reasons. But for many deep tech startups, fundraising norms matter a lot.

This is also where IP strategy matters. In deep tech, your inventions are often the asset investors care about most. Tran.vc helps founders set up that asset early through patent and IP support worth up to $50,000 in-kind. If you want that kind of leverage, you can apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

The most misunderstood word in founder tax: “dividends”

Why founders assume dividends are irrelevant

Founders often think dividends are something that old, public companies do. Many startups never pay a dividend, because profits are reinvested or the company is still in growth mode.

That assumption can be safe, but it can also create blind spots. Tax rules do not care what you intended. They care what happened. And certain transactions can look like a dividend even if you never used that word.

If you remember one idea from this section, let it be this: the IRS has its own language. Your internal language does not matter unless you back it up with documentation that matches tax rules.

Constructive dividends: the dividend you never meant to create

A constructive dividend is a benefit you receive from the company that is treated like a dividend for tax purposes.

This can happen when the company pays personal expenses. It can happen when the company gives you assets for personal use without treating it as compensation. It can happen when rent, travel, meals, or even family expenses get paid through the business without proper structure.

In early startups, these things happen because boundaries are messy. You might work from home, travel for work, and mix personal and business costs in the same week. The problem is not that you have mixed life and work. The problem is when the accounting record does not clearly support the business purpose.

How to reduce the risk without becoming rigid

You do not need to become paranoid. You do need a simple system.

If an expense is business-related, keep proof and a short note on why it was business-related. If an expense is personal, do not run it through the business. If you accidentally do, reimburse the company quickly and record it correctly.

It is boring, but it is one of the easiest ways to avoid creating a tax problem that looks far larger than it really is.

Paying yourself: where founders accidentally create tax pain

Salary is usually the cleanest tool in a C-Corp

If your company is a C-Corp and you work in the business, paying yourself through payroll is often the cleanest method.

This is because salary is a business expense. That means it can reduce corporate taxable income. Then you pay personal tax on your salary, like any worker would.

It is not “free,” because payroll taxes exist. But it is clear. It is easy to defend. And investors like seeing founders paid in a normal, documented way once there is enough cash.

The trap: taking money without a label

A founder sees money in the account and moves it to their personal account. They plan to “sort it out later.” Later becomes months. Then tax time arrives.

The issue is not only tax. It is also governance. Some companies need board approval for certain payments. Some payment types can create legal issues if the company is raising money or has other shareholders.

A simple rule helps: every transfer should have a reason that matches a category. Payroll, reimbursement, loan, or documented distribution. If you cannot label it, do not do it.

What “reasonable salary” means in plain terms

Founders hear “reasonable salary” and imagine a single number. In practice, it is more like a story that needs to make sense.

If your startup has little revenue and short runway, a modest salary can still be reasonable, because the company cannot support more. If the startup is profitable and has stable cash flow, a near-market salary becomes more reasonable.

The goal is to avoid extremes that look suspicious. Paying yourself almost nothing for years while the company prints money can raise questions in certain structures. Paying yourself a huge salary when the company is struggling can also raise questions, and it can upset investors.

A good approach is to pick a salary that fits your cash reality and document why it is set that way. Documentation sounds formal, but it can be as simple as a note in board minutes or a founder agreement.

Why founder pay becomes an investor conversation

Many founders think paying themselves is purely personal. But investors often care, because it affects burn and runway.

If founder pay is too high, runway shrinks. If founder pay is too low, founders burn out or take consulting work on the side, which slows the company.

The best founder pay plan is one that is stable and predictable. Investors do not need it to be perfect. They need it to be thoughtful.

Equity compensation and double taxation risk

Stock and options are not “cash,” but they can create tax events

Equity feels like a paper promise. But taxes can show up even before you sell.

Different equity tools have different tax timing. Some trigger tax when granted, some when vested, some when exercised, and some when sold. If you mix up the timing, you can end up owing tax without having cash to pay it.

This is one of the reasons founders need to understand equity basics early, even if they hate paperwork.

The simple founder view: timing is everything

When you receive equity, ask three timing questions.

When does it become yours in a real way? When does the IRS treat it as income? When can you sell it?

If tax happens before liquidity, you can end up with a personal cash problem. That is not double taxation in the classic dividend sense, but it is still a painful “tax twice” feeling because you pay tax without being able to turn equity into cash.

Why IP and equity planning should match

Deep tech founders often create value through inventions, models, and systems. Those assets should sit inside the company cleanly, with proper assignments and filings where needed.

If IP is unclear, equity value is harder to defend. That can change deal terms and can force messy restructuring later, which can trigger tax issues if assets need to move.

Tran.vc helps founders build clean IP foundations early, with up to $50,000 of in-kind patent and IP services. If you want to protect the core of your tech while you build, apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

The “double taxation” conversation founders should have before raising

Fundraising often pushes you toward C-Corp reality

Many founders start as an LLC because it is fast and cheap. Then an investor says they need a Delaware C-Corp for the round.

That conversion can be smooth, but it can also create tax complexity depending on timing, ownership, and how assets are held. The earlier you plan for your likely fundraising path, the fewer surprises you face.

If you already know you want venture funding, starting clean can save you a lot of cleanup later.

Clean cap table and clean accounting reduce tax risk

Tax risk often hides in messy records. Missing invoices, unclear founder draws, mixed expenses, and undocumented equity grants create confusion. Confusion creates delays. Delays create cost.

A clean system does not mean fancy software. It means consistent habits and clear records.

A simple sanity check founders can run

If you were forced to explain every dollar that left your company last month, could you do it clearly?

If the answer is no, that is not a shame moment. It is a signal. Fix it now while volume is low. Later, fixing it can take weeks and can distract you from shipping product.