When you raise money across borders, the term sheet stops being a “simple” deal summary and starts becoming a translation project.

Not just language. Legal systems. Tax rules. Currency movement. How courts work. How fast you can enforce a contract. Even what a “share” really means in that country.

And here’s the hard truth: most founders do not lose control because they were careless. They lose control because they signed something that sounded normal in one place, but works very differently in another.

If you are building robotics, AI, or deep tech, this risk is even higher. Your value is often in your code, your data, your models, your edge cases, your know-how, and your patents. Cross-border term sheets can pull on those threads in sneaky ways—sometimes without saying “IP” in the headline.

Tran.vc exists for this exact moment. We help technical founders turn real invention into real assets early, so your leverage is not only “future growth.” It’s also “protected value.” If you want help before you sign anything, you can apply anytime here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Below is the short intro. If you want, I’ll continue into the main body right after this, and we will go clause by clause where things get messy.

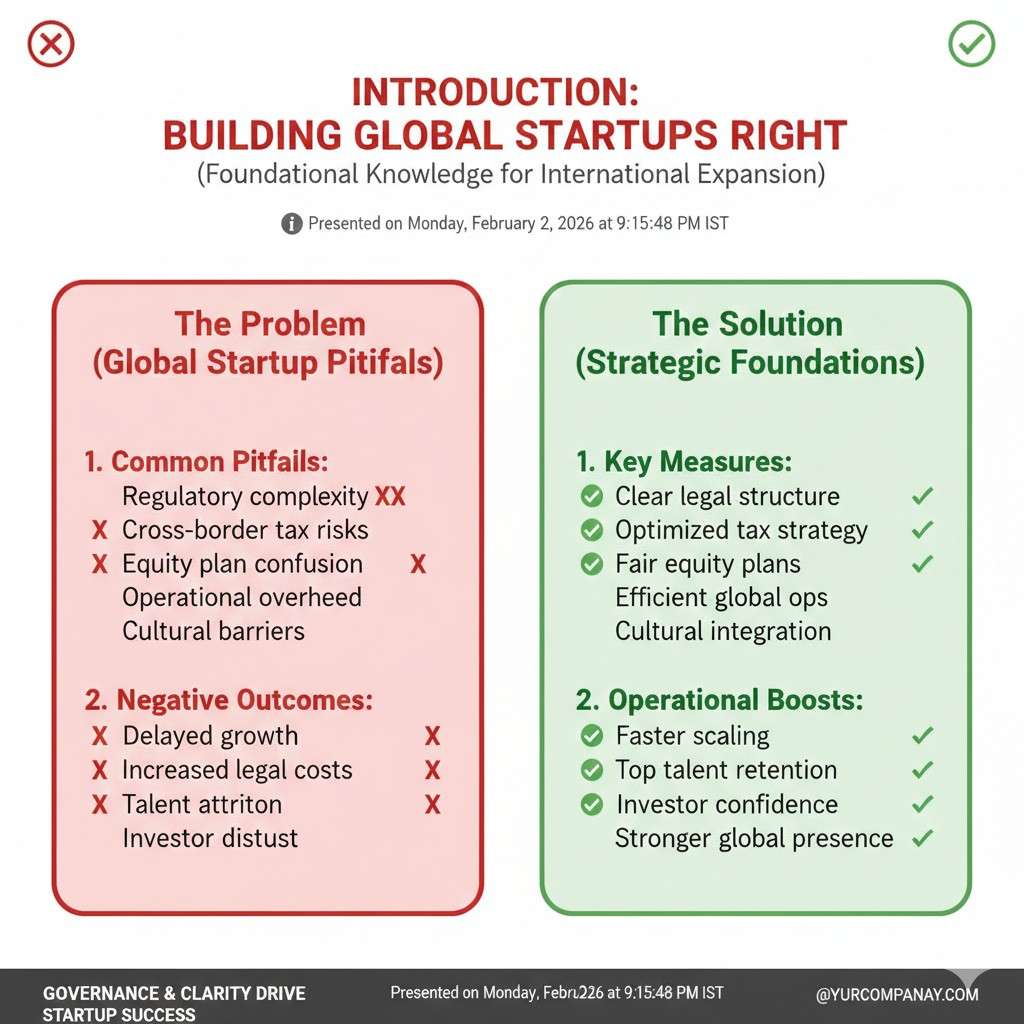

Introduction

A term sheet is supposed to be a handshake on paper. It is not the full contract, but it sets the rules for the full contract. That is why it matters so much.

Now add one more fact: in a cross-border deal, both sides often think the term sheet means what it means “back home.” They nod, they move fast, and they assume the lawyers will sort details later.

That is when trouble shows up.

Because “later” is when the hard parts get locked in. And the hard parts are not always obvious. A small line about governing law can change who wins a fight. A single word in a liquidation clause can shift millions. A “standard” option pool line can create a tax shock in the wrong country. A board seat can trigger a foreign filing duty for your patents. Even a simple right to get information can become a data export issue.

This article is about the clauses that look normal, but get messy when borders are involved. Not in theory. In the real world, where you are trying to ship product, hire, file patents, and close a round without losing months.

If you are raising from an investor in another country, or you are a foreign founder raising in the US, the goal is not to “win the term sheet.” The goal is to understand where the hidden edges are, and remove them before you sign.

If you want Tran.vc to help you build IP leverage early—so you do not walk into these talks empty-handed—you can apply anytime at: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Cross-Border Term Sheets: Clauses That Get Messy

Why this gets hard so fast

A cross-border term sheet feels like a normal term sheet, right up until it doesn’t. You will see familiar words like “preferred,” “pro rata,” “board seat,” and “liquidation preference.” The problem is that each word carries baggage from local law and local habit.

In one country, a “standard” clause is mostly symbolic. In another, that same clause is enforced exactly as written, even if it produces a harsh result. This gap is where founders get surprised, and where investors sometimes get frustrated too.

The fastest way to stay safe is to treat the term sheet like a map of future power. Every clause is either giving someone a lever, or limiting a lever. When borders are involved, those levers can become longer than you expect.

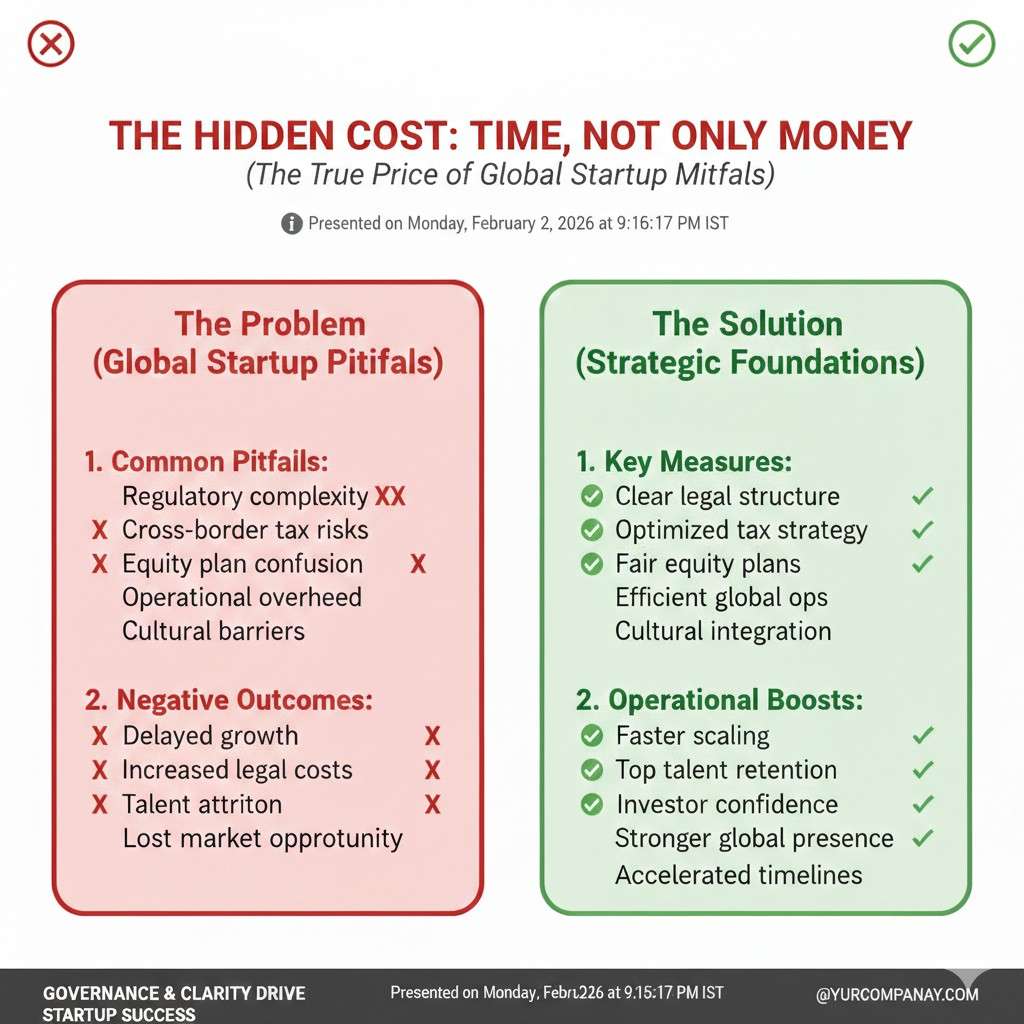

The hidden cost is time, not only money

Most founders worry about valuation and dilution first. Those matter, but cross-border friction often hits you in a different place: time. Deals drag because parties cannot agree on mechanics, filings, approvals, and who owns what under which system.

If you are building deep tech, time is not a soft cost. It affects hiring, product deadlines, patent filing windows, and customer momentum. A “minor” term sheet mismatch can turn into a two-month delay that you never get back.

What this article will do for you

I will walk through the clauses that cause the biggest mess across borders. I will not try to scare you. I will show you where the traps are, why they happen, and what clean wording and clean structure often looks like.

When you know the pressure points early, you can negotiate calmly. You can also avoid late-stage legal surprises that force you to accept worse terms just to close.

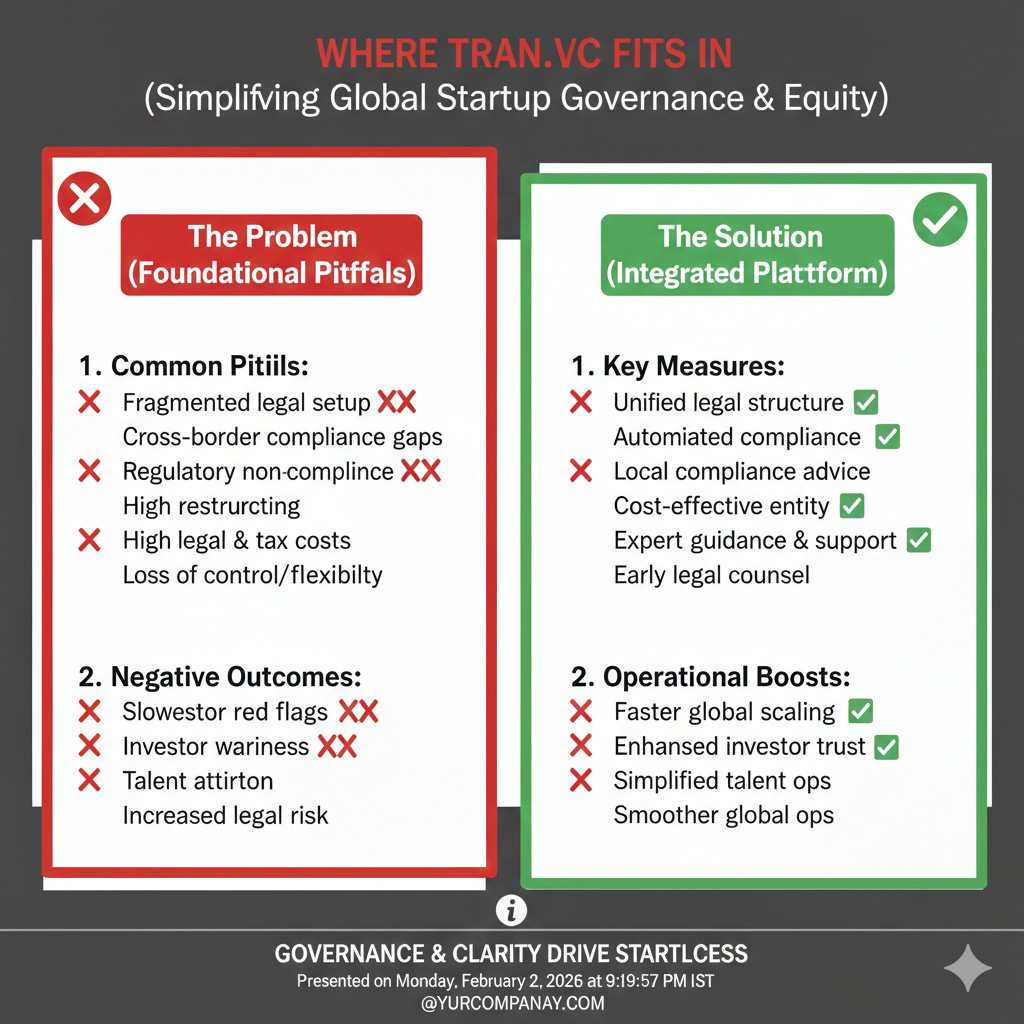

Where Tran.vc fits in

If your company’s edge lives in algorithms, models, robotics design, data flows, or new methods, your IP is part of your deal leverage. Cross-border term sheets often create IP risk without announcing it.

Tran.vc helps technical founders lock down defensible IP early, so you are not negotiating from hope. If you want help shaping your IP plan before you sign a term sheet, you can apply anytime at: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Start with the frame: what “country of the company” really means

Incorporation is not a detail

In a cross-border round, the first “term” is sometimes not even written in the term sheet. It is the assumption about where the company lives. That single fact controls what shares are, how boards work, how exits get taxed, and what investor rights are possible.

A US investor may assume you will be a Delaware C-Corp. A founder in another country may assume they can raise money where they are, keep the entity there, and still get “US-style” terms. Sometimes that works. Many times it does not.

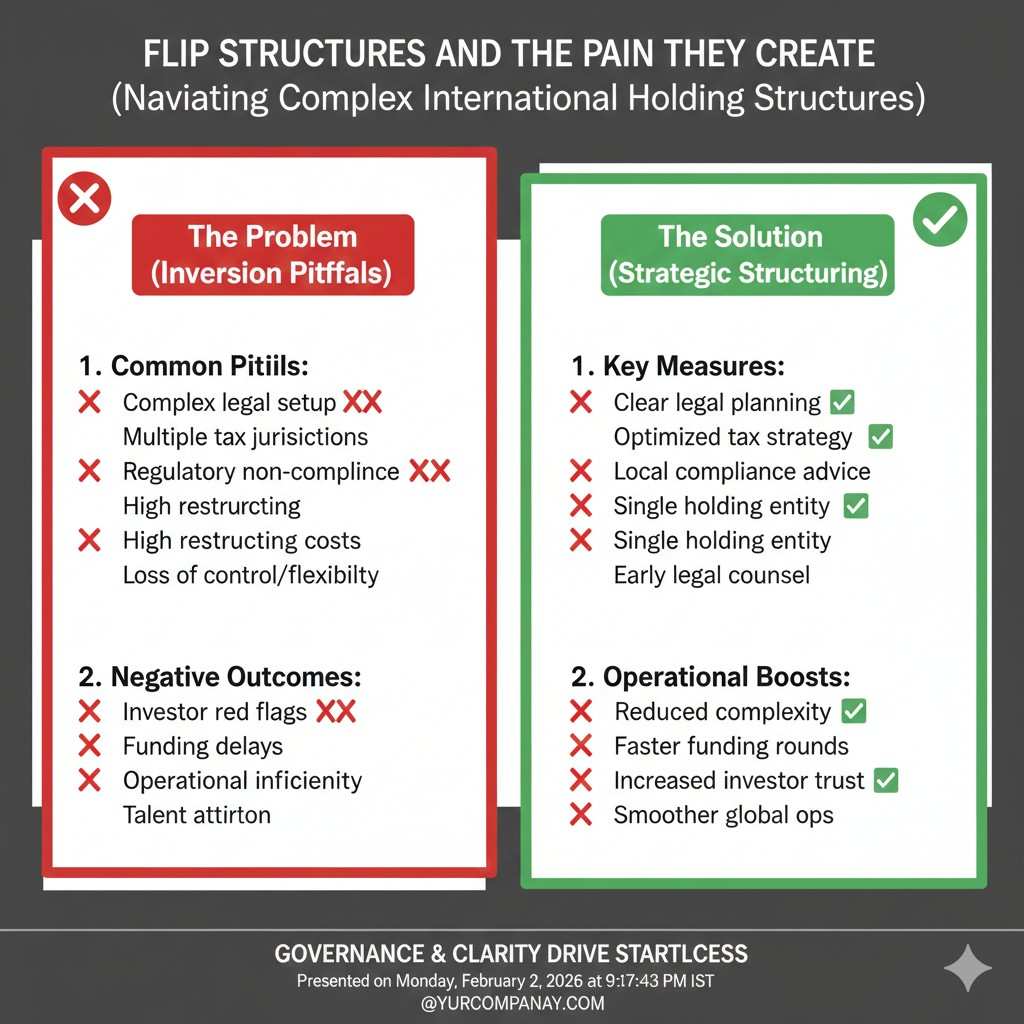

Flip structures and the pain they create

A “flip” is when you create a new parent company in another country and move ownership under it. It sounds simple when people say it quickly. In practice, it can be slow, expensive, and risky if it is done under deadline pressure.

The term sheet may say “closing is conditioned on a flip.” If you accept that line without understanding the steps, you can end up in a closing trap. You are committed to a timeline you do not control, and the investor can use delays to renegotiate.

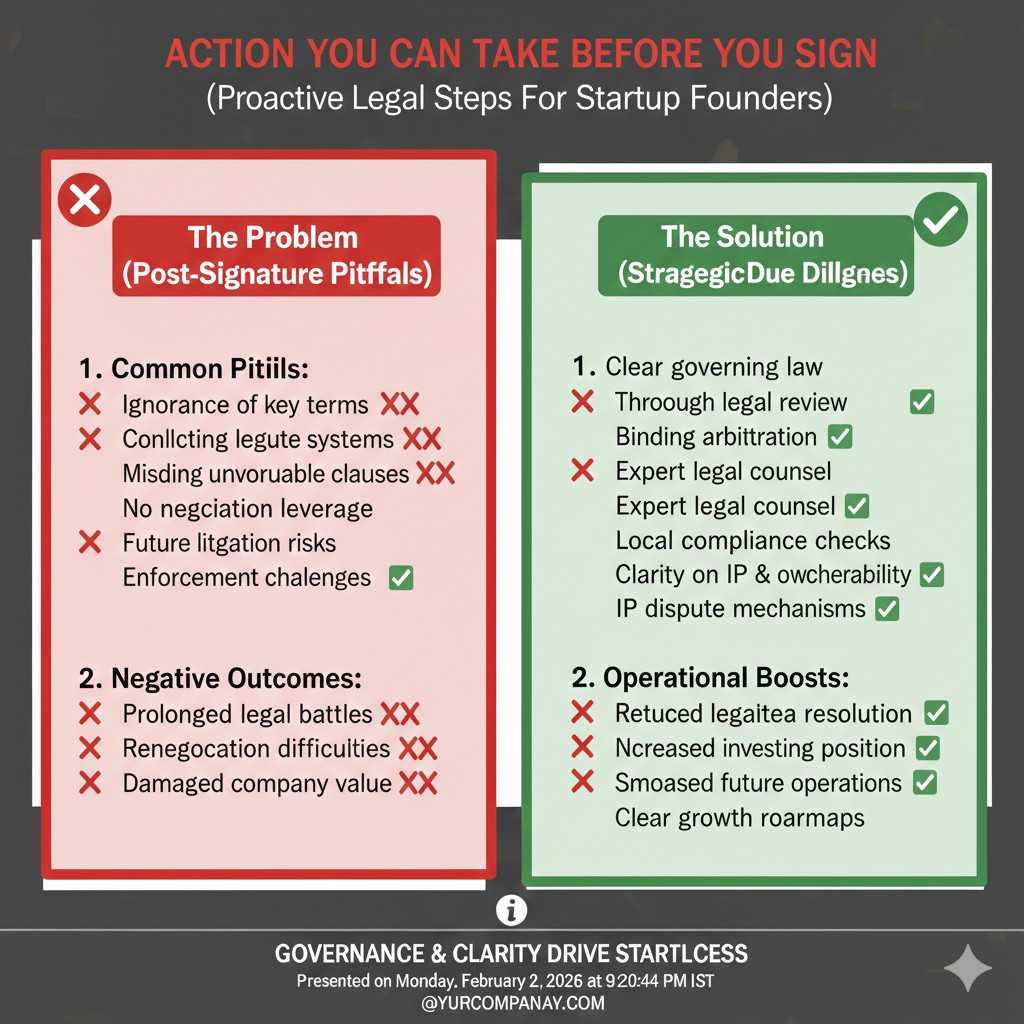

Action you can take before you sign

Before you accept a term sheet, ask for a clear picture of the target structure, not just the word “flip.” You want to know what entity will issue shares, what happens to existing shareholders, and how IP assignments will be handled during the move.

If your IP was created in a different country than the new parent company, get serious about chain of title. If you cannot prove ownership cleanly, you can lose negotiating power at the worst time.

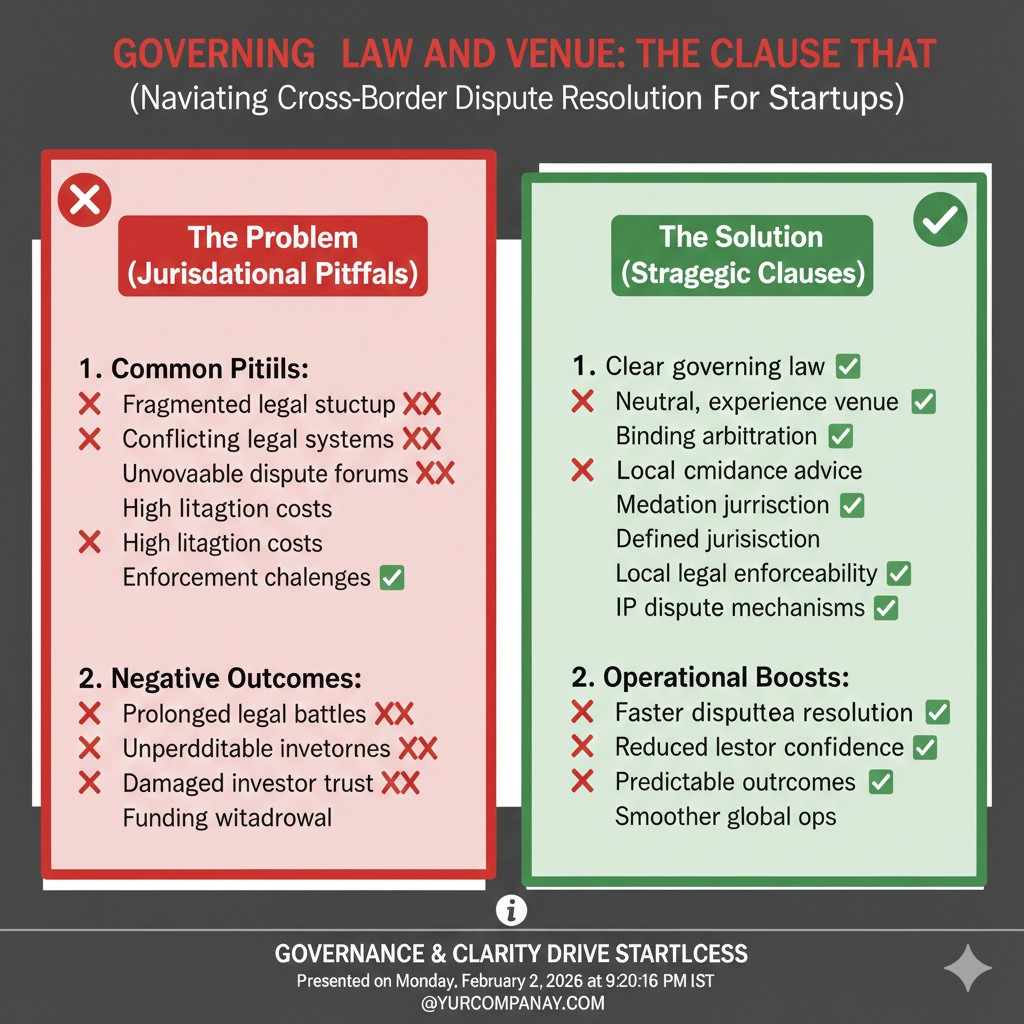

Governing law and venue: the clause that decides who can fight

“Governing law” is not just legal filler

This clause tells you which legal system interprets the deal. Two contracts with the same words can have different meaning under different systems. In some places, courts lean heavily on the written text. In others, courts consider broader fairness arguments.

Founders often skip this clause because it feels abstract. But it controls how safe you are if something goes wrong. If you cannot enforce your rights, your rights are only paper.

Venue matters more than you think

Venue is where disputes are heard. If the venue is far away, expensive, and slow, you may never bring a claim even if you are right. The investor may know that, and it can change how they behave later.

Some term sheets mix court venue with arbitration. Arbitration can be faster, but it can also be expensive, and some arbitration awards are harder to enforce across borders depending on the countries involved.

Action you can take before you sign

Do not argue about law and venue only on principle. Argue on practicality. Ask: if we disagree, where can we resolve it in a way that is real, affordable, and enforceable?

If the investor insists on a home venue, push for a neutral option like arbitration in a neutral seat, or a venue tied to the company’s place of incorporation. The goal is not to “win.” The goal is to avoid a clause that makes you helpless.

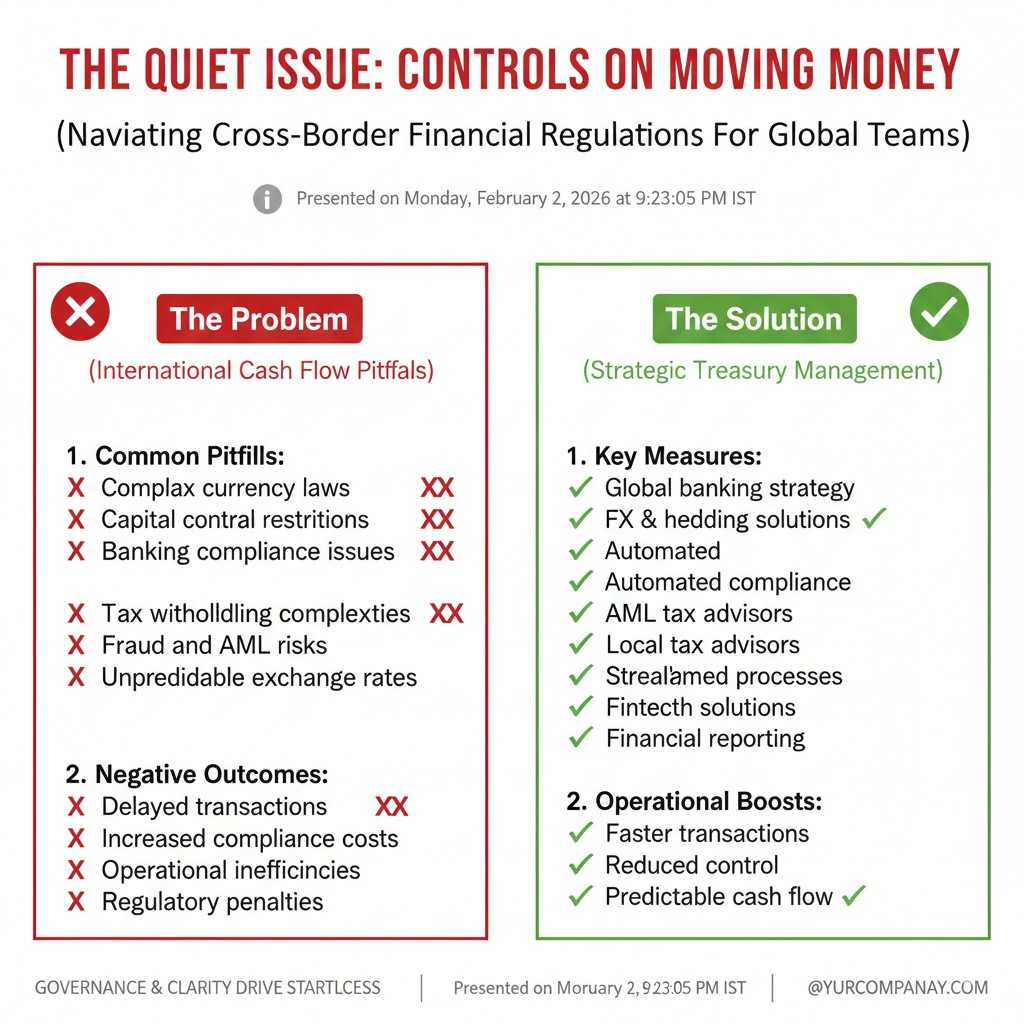

Currency, pricing, and FX: the math that changes after you sign

Cross-border money moves in real life, not in spreadsheets

If an investor is wiring in USD and your team spends in another currency, you have an FX risk. Even if the round is priced in your local currency, investors often think in their home currency.

This becomes messy when the term sheet is silent on how pricing is calculated at closing. A small timing difference between signing and closing can change the effective valuation because the exchange rate moved.

The quiet issue: controls on moving money

Some countries restrict how money comes in and how money goes out. If the investor’s money is stuck in an approval queue, you may miss payroll. If the company cannot send money out easily, paying vendors and contractors across borders becomes painful.

In the worst cases, a term sheet can promise something that local rules do not allow. That leads to last-minute restructuring, which leads to more legal work, which leads to delays and stress.

Action you can take before you sign

Get clear on the currency of the round, the exchange rate reference if needed, and what happens if closing is delayed. If your country has inbound investment filings, build that timeline into the deal plan, not as an afterthought.

Also, be careful with “pay-to-play” type language that assumes investors can fund quickly. If money movement is slow, you may get penalized for delays you did not cause.

Liquidation preference: where “standard” becomes very non-standard

The headline number is not the full story

A “1x non-participating” preference is often treated as founder-friendly in the US. But cross-border term sheets can twist this through definitions, ranking, and payout mechanics that are shaped by local company law.

Sometimes the mess comes from how “liquidation event” is defined. In one market, it might include a sale and a merger. In another, it might also include asset sales, reorganizations, or even certain share transfers.

Preference stacking and seniority disputes

When multiple investors from different places invest over time, they may expect different seniority rules. One investor might assume everyone is pari passu, meaning equal. Another might assume each new round is senior unless it is stated otherwise.

If your term sheet does not state seniority cleanly, you can end up with investors fighting each other at exit. That fight lands on you, and buyers do not like messy cap tables.

Action you can take before you sign

Ask for the preference in plain language examples, not only legal wording. If the investor cannot explain the exit waterfall clearly with numbers, treat that as a warning sign.

Also, ensure the term sheet states whether the new preferred is senior, junior, or equal to existing preferred. This should be explicit, not implied.

Control terms: boards, vetoes, and the “consent list” problem

Board seats can trigger unexpected duties

In some cross-border setups, adding a foreign director can create compliance duties. It can change what filings you must do, and how meetings must be held. It can also affect whether certain tech falls under export or national security review, depending on the countries involved.

Even if the term sheet is silent, the board structure may force changes to how you operate. This is especially true when your product touches robotics, autonomy, advanced sensors, or sensitive data.

The consent list is where founders lose speed

The term sheet may include a list of actions that require investor consent. In one market, this list is short. In another, it becomes a long menu of normal startup moves: hiring executives, signing large contracts, changing budgets, issuing options, or moving IP.

Cross-border investors sometimes ask for broader vetoes because they feel farther away and want comfort. But broad vetoes can slow you down so much that you miss your own goals.

Action you can take before you sign

Focus on narrowing consent rights to truly big items. Tie them to clear thresholds, like “contracts above X,” or “debt above Y,” and keep day-to-day operations in founder control.

Also, define what “budget” means if budget changes require consent. If you do not define it, a normal shift in spending can become a negotiation.

Information rights and inspection: when “transparency” hits privacy and data rules

Investor updates can become a legal problem

Investors want reports. That is normal. But cross-border sharing can trigger data and privacy rules, especially if your reports include customer data, user analytics, or employee info.

Some countries restrict exporting certain data. Some contracts with customers restrict sharing. A term sheet that gives broad inspection rights can force you into a conflict between investor demands and legal duties.

The tricky part is how wide “books and records” can be

“Books and records” sounds like accounting. In some documents, it is defined so broadly that it includes code repositories, model weights, training sets, and internal research notes.

Most investors do not intend to read your source code. But a broad right can still create risk, especially if the investor has other portfolio companies in related areas.

Action you can take before you sign

Limit information rights to what is necessary: financial statements, KPIs, and reasonable operating updates. If inspection rights exist, add guardrails so that sensitive IP and regulated data are protected.

You can also add language that allows redaction or aggregation for privacy and customer obligations. This keeps you compliant without looking secretive.

IP clauses that sneak in through “standard” language

IP is often affected even when the term sheet does not say “IP”

Cross-border term sheets can change IP risk through side doors. A simple clause about assignments, inventions, or confidentiality can be written in a way that conflicts with local employment laws.

For example, in some countries, employee invention rights are not fully assignable by contract. If you assume a US-style invention assignment works everywhere, you can end up with gaps in ownership.

Founder vesting and IP assignment are linked

Founder vesting clauses are common. In cross-border deals, vesting can also be used to pressure founders around IP transfer, especially during restructuring or flips.

If a term sheet makes vesting acceleration depend on investor consent, that consent can become leverage in any later dispute. If your inventions are central to the company, that leverage matters.

Action you can take before you sign

Run an IP ownership check early. Confirm that every founder and key contributor has signed proper invention assignment documents that work under local law.

If you are not sure, fix it now, not during the round. Tran.vc can help you do this the right way and also build a patent plan that supports your next raise. You can apply anytime at: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Option pools and tax shocks: the clause that hurts quietly

Why option pools get weird across borders

An option pool sounds like a simple hiring tool. In many cross-border rounds, it becomes a fight about who pays for future hires. Investors often push for the pool to be “carved out” before the valuation is set, so the dilution hits founders more than investors.

That is not new. The messy part is that the option pool may not even work the same way in your country. In some places, options are hard to issue, slow to approve, or create heavy tax for employees at the wrong time.

If you sign a term sheet that demands a big pool, but your local plan cannot support it cleanly, you will be stuck. You either delay hiring while lawyers rebuild the plan, or you hire and create tax pain that makes people quit.

When the pool size hides a control move

A large pool can also be used to shape control. If the board must approve option grants, and an investor has a board seat plus veto rights, they can influence who gets equity and when.

In a cross-border setup, this can become more intense because investors may want “tight governance” due to distance. They might frame it as risk control, but it can still reduce founder freedom in everyday recruiting.

What to do before you accept the number

Ask what the pool is meant to cover. Is it for 12 months of hiring or 24? Is it for engineers only, or also sales and operations? If the pool is large, ask the investor to show the hiring plan that justifies it.

Also ask how the pool will be implemented in the actual legal system you are using. If you are not sure, do a quick check with counsel who works in that country, not only the investor’s home country.