Closing a cross-border round is not “just fundraising with a few extra emails.” It is fundraising plus banking, tax, law, and paperwork—across at least two systems that do not like each other. The good news is this: if you understand the timeline and the documents early, the close stops feeling scary. It becomes a project you can run like an engineering sprint.

At Tran.vc, we see this pattern a lot with deep tech teams. A robotics founder builds in India, incorporates in the US, sells to global customers, and raises from an angel group in Singapore plus a seed fund in California. Or an AI team has a US parent, but the core engineers sit in Europe. Cross-border is normal now. But “normal” does not mean “simple.”

This article is here to make it simple.

When you read “timeline,” do not think of it as a single date. Think of it as a chain. One link slips, the whole chain moves. The best founders treat the close like a launch: define the path, gather the parts, test the weak spots, then ship.

Also, one important note. Many founders wait to think about IP until the round is almost done. That is a mistake, especially in robotics and AI. Investors may not ask for patents on the first call, but they will ask later, and they will not like vague answers. Strong IP planning also helps you pick the right country structure, the right employee invention clauses, and the right timing for public talks. Tran.vc invests up to $50,000 in in-kind patent and IP services so you can build a real moat early, not after the market copies you. If you want help building that foundation while you raise, you can apply anytime here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Now, let’s start with what a “cross-border close” really means, in plain terms.

A round is “cross-border” when money, people, or company entities sit in more than one country. That can happen in a few common ways.

Sometimes your company is incorporated in one place, but investors are in another. A Delaware C-Corp raising from an Indian angel is cross-border. A Singapore Pte raising from a US fund is cross-border. This is the most common case.

Sometimes your company is in one place, but your team is not. You might have a US parent company, but engineering is in Poland or India. This adds key documents around hiring, invention assignment, and who owns what.

Sometimes your customers, revenue, or regulated product touches other countries. Robotics often does, because hardware ships and gets installed. That can trigger extra checks, like export rules and product compliance. It can also trigger investor questions about where value is created.

And sometimes you have more than one entity. You might have a US holding company and a local operating company. This is common when founders start local, then “flip” to the US later. This can work well, but it creates a document trail investors will want to see.

If any of this sounds like you, the closing will need more than the standard startup paperwork. You will still do the core round documents, yes. But you will also do “bridges” between systems: tax forms, money movement proofs, approvals, and sometimes government filings.

The biggest risk in cross-border rounds is not that the law is impossible. The biggest risk is time. The close can drag, and when it drags, two bad things happen.

First, founders lose momentum. The team feels it. Customers feel it. You stop shipping because you are stuck in docs.

Second, investors lose patience. Not because they are mean, but because they have their own timelines. Their legal team schedules. Their investment committee meetings. Their end-of-quarter targets. When your close misses a window, it creates friction.

So the goal is simple: remove surprises. Most surprises come from missing documents or unclear facts.

Before we get into a clean timeline, you need to understand how closings really happen in practice. Founders imagine a single “closing day” where everyone signs and money hits the bank. That sometimes happens in small local rounds. But in cross-border rounds, it often closes in steps.

You may do a first close with the lead investor, then a second close with smaller investors later. This is called a rolling close. It is normal. It is also useful because your lead’s money can come in while you finish paperwork for the rest.

You may also have “soft circle” and “hard close” moments. Soft circle means people say yes and you agree on terms. Hard close means signed documents and funds received.

When founders say, “We are closing next week,” they often mean “we think everyone will sign next week.” In cross-border rounds, signing is only half the story. Funds have to clear. Banks have to approve wires. Some investors need extra forms before they can send money. Some countries require a filing after the money arrives. If you treat the close as only signatures, you will be surprised.

A better mental model is three tracks running at the same time:

The legal track: term sheet, diligence, final agreements, signatures.

The money track: bank readiness, wire details, approvals, forms, proof of funds.

The compliance track: tax forms, anti-money-laundering checks, foreign investment notices, board approvals, and sometimes local regulator steps.

A founder who wins cross-border closings keeps these three tracks moving together. That means you start some steps earlier than you feel ready to. Not because you are rushing, but because cross-border processes have hidden delays. A bank in one country may take three days to confirm a new beneficiary. A compliance team may take a week to clear a KYC review. A founder who waits until “after the docs” to do money and compliance work loses weeks.

Let’s make this concrete with a realistic timeline.

Assume you are raising a seed round with at least one investor outside your company’s home country. You have a lead investor, plus a few smaller checks from other places. You are not a public company. You are a normal early-stage startup.

A smooth cross-border close often takes six to ten weeks from signed term sheet to money in the account. It can be faster, but you should not plan your runway based on the best case. Plan for a normal case. If it finishes early, you win. If it slips, you are safe.

Here is what happens in those weeks, in human language.

Week 0 is the term sheet. You agree on price, size, basic rights, and who leads. Many founders feel relief at this step. You should feel relief, but you should also switch gears immediately. Term sheet is the start of execution, not the end of sales.

Within the first two days after the term sheet, you want two things done.

First, pick the “document path.” In seed rounds, it is often either a priced equity round or a convertible instrument like a SAFE or note. Some countries and some investors strongly prefer one. If you already have a US company and US lead, SAFEs can be easy. But if you have non-US investors, some will not use SAFEs. Some can, some cannot. A Singapore family office might want a note. A European fund might want equity. Even when they say they are “fine with a SAFE,” their back office may still ask for extra side letters. The point is: decide early so your lawyers draft the right set of papers.

Second, create a single source of truth for diligence. This is usually a data room. It can be a simple folder with clear naming. The goal is not fancy. The goal is fast answers. Cross-border investors will ask the same questions in different ways. If you do not have clean files, you will waste time.

Within the first week, you want to handle “foundation checks.” These are the things that, if broken, will stop the deal later.

The first is company structure. Investors want to know: what entity are they investing in, and does it actually own the business? If you have a US parent and a foreign subsidiary, they will ask: who owns the subsidiary shares, how money moves up, and who owns IP created by the subsidiary team. If you have a “flip” history, they will ask for the flip documents. If you have any side agreements between founders, they will ask to see them. If your cap table has odd items, they will ask why.

The second foundation check is IP ownership. In robotics and AI, this is not optional. If your engineers are in another country, you must be able to show that inventions are assigned to the company. If you have contractors, you must show proper assignment language. If you used open-source software in a core way, you must be able to explain it. This is one area where founders often get hurt because they assume “we built it, so we own it.” Law does not work like that. Paperwork matters.

This is also where Tran.vc often helps early. We build an IP plan that fits your round timeline. We help you decide what to file now and what to hold. We help you make sure your invention assignments, contractor papers, and patent story are clean before investors dig. If you want that support, you can apply here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Now comes the part founders dread: diligence. But if you run it right, it is just structured Q&A.

Diligence has two layers.

There is business diligence: market, product, traction, roadmap, team.

And there is legal and financial diligence: cap table, entity docs, contracts, IP, HR, taxes.

Cross-border adds a third layer: cross-border compliance diligence. Investors want comfort that sending money to you is allowed, that your company can receive it, and that you will not create tax problems for them.

The best way to keep diligence calm is to expect it and pre-answer it. If you wait for questions, you will feel attacked. If you prepare the common documents, you will feel in control.

This is where “timeline and documents” starts to become real. Because documents are not random. They are tied to specific points in time.

Think of it like this: each document exists to answer one fear.

A term sheet answers: “Are we aligned on the deal?”

A cap table answers: “Who owns what?”

An incorporation certificate answers: “Is this company real?”

An IP assignment answers: “Does the company own the invention?”

A stock purchase agreement answers: “Are we buying valid shares?”

A board consent answers: “Did the company approve this?”

A wire instruction letter answers: “Where does the money go?”

A tax form answers: “Will we have withholding or reporting issues?”

In cross-border rounds, fears multiply, so documents multiply. That is why having a clean list matters.

But you asked for an introduction, and this is still the start. So I will close the intro with one practical promise.

If you can do three things early, your close will be much faster.

One, clean cap table and clear entity story.

Two, clean IP chain of title, meaning your company owns what it should own.

Three, bank and compliance readiness so money can move without panic.

If you want Tran.vc to help you get that IP chain clean and investor-ready while you raise, apply anytime here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

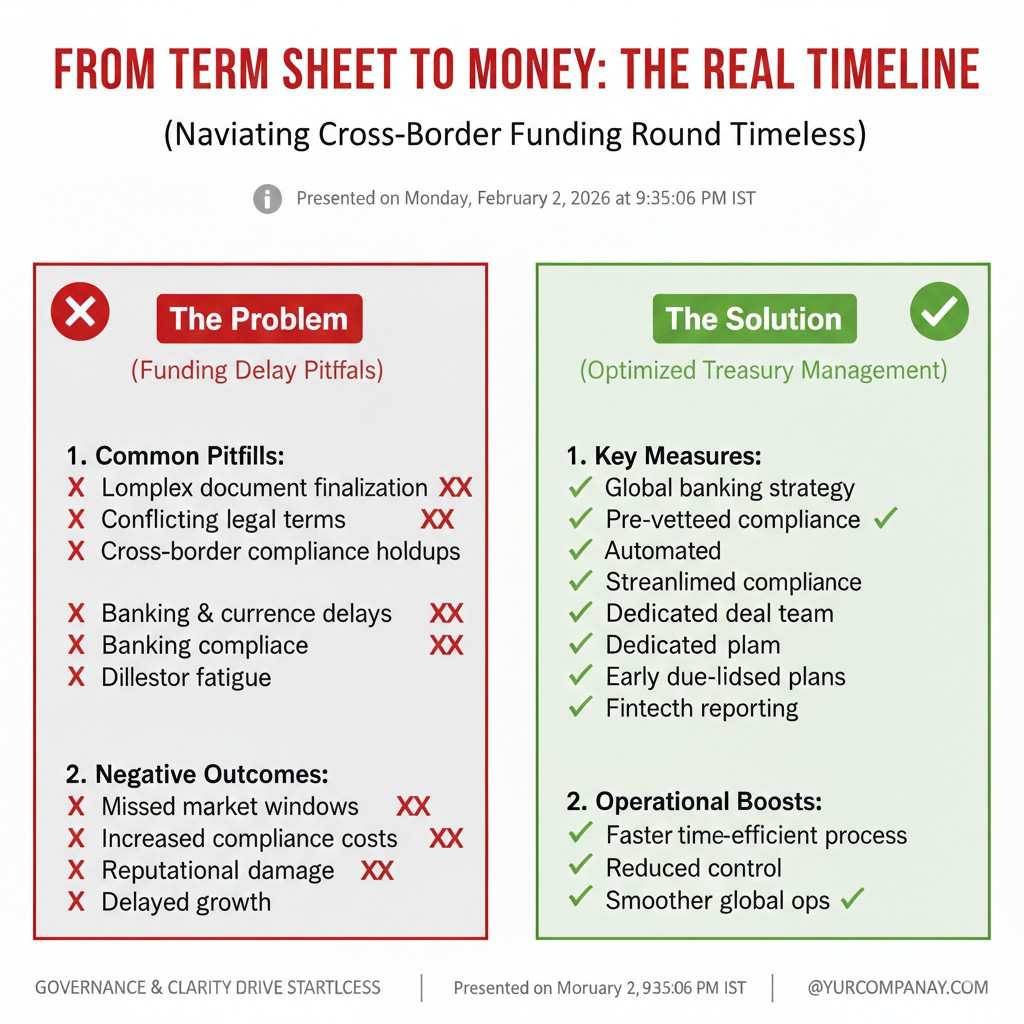

From Term Sheet to Money: The Real Timeline

What “Week 0” Really Means

Once the term sheet is signed, the round is not “almost done.” It has only switched from selling to executing. In cross-border rounds, execution has more moving parts than most founders expect. That is why many closes slip even when the investor is excited.

In practical terms, Week 0 is when you lock the shape of the deal and start preparing the file trail. If you wait until lawyers begin drafting to organize this, you will lose days, then weeks. The fastest closings happen when the founder treats the term sheet like a starting gun, not a finish line.

Your Three Parallel Tracks

A cross-border close runs on three tracks at the same time. Legal is the track founders can see, because it comes with redlines and signature requests. Money is the track founders feel later, because wires can fail without warning. Compliance is the track founders often ignore, until someone’s bank suddenly asks for proof and the close freezes.

If you keep these tracks moving together, the round closes smoothly. If one track lags, it pulls the other two behind it. The goal is not perfection. The goal is removing surprises before they become emergencies.

The One Decision That Changes Everything

Early in Week 0, you must decide the document path. In simple terms, investors either buy equity now, or they invest through a convertible tool that turns into equity later. Different countries and different investor types have strong preferences here, and those preferences are not always negotiable.

If you pick a structure that an overseas investor cannot process, you will discover it late, after legal work is already done. That is painful and expensive. So you want the lead investor and counsel aligned on structure within the first few days, even if some details still evolve.

Tran.vc Note on IP Timing

Many deep tech founders delay IP decisions because they assume investors will not ask. In cross-border rounds, investors almost always ask, because IP is often the main asset that crosses borders. If engineers build in one country and investors fund in another, investors want proof that the company owns the inventions.

Tran.vc helps teams build an IP plan that fits the round timeline, so diligence does not turn into a scramble. If you want that support while you raise, you can apply anytime at: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

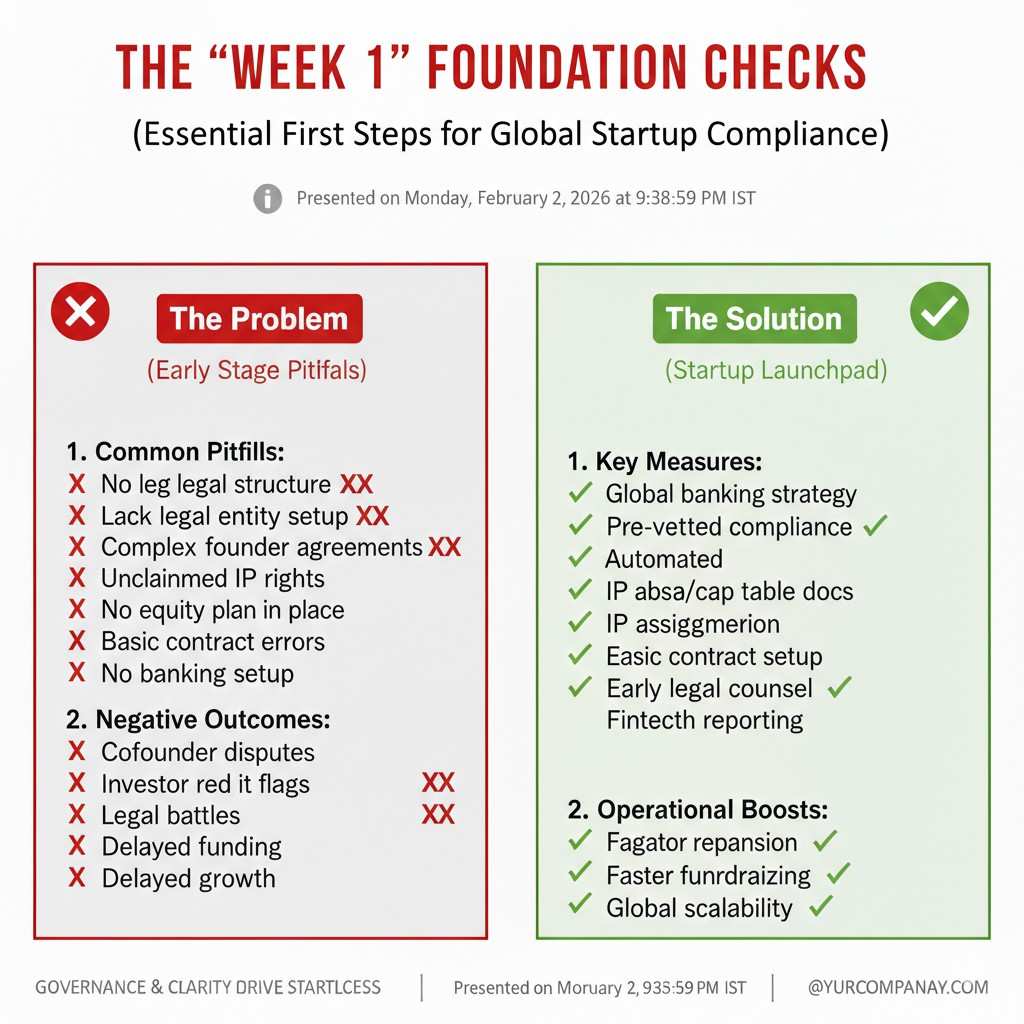

The “Week 1” Foundation Checks

Entity and Ownership Clarity

The first set of checks is about whether the investing entity actually owns the business. Investors are not trying to be difficult when they ask this. They are protecting themselves from a nightmare scenario where they invest in the wrong entity, or where core assets sit somewhere else.

If you have only one company in one country, this is usually straightforward. If you have a parent and a foreign subsidiary, it is more complex. The investor will want to see who owns the subsidiary, how it is controlled, and whether the parent has clear rights over cash and IP.

The Cap Table Must Tell a Simple Story

Your cap table is not just a spreadsheet. It is a narrative of trust. A clean cap table helps investors say yes quickly. A messy cap table creates questions that feel small but take forever to resolve, especially when signatures must come from people in other time zones.

Cross-border deals are more sensitive to cap table confusion because many investors will run extra checks. They may also need to explain the ownership picture to their own compliance teams. If the cap table is unclear, they slow down until it becomes clear.

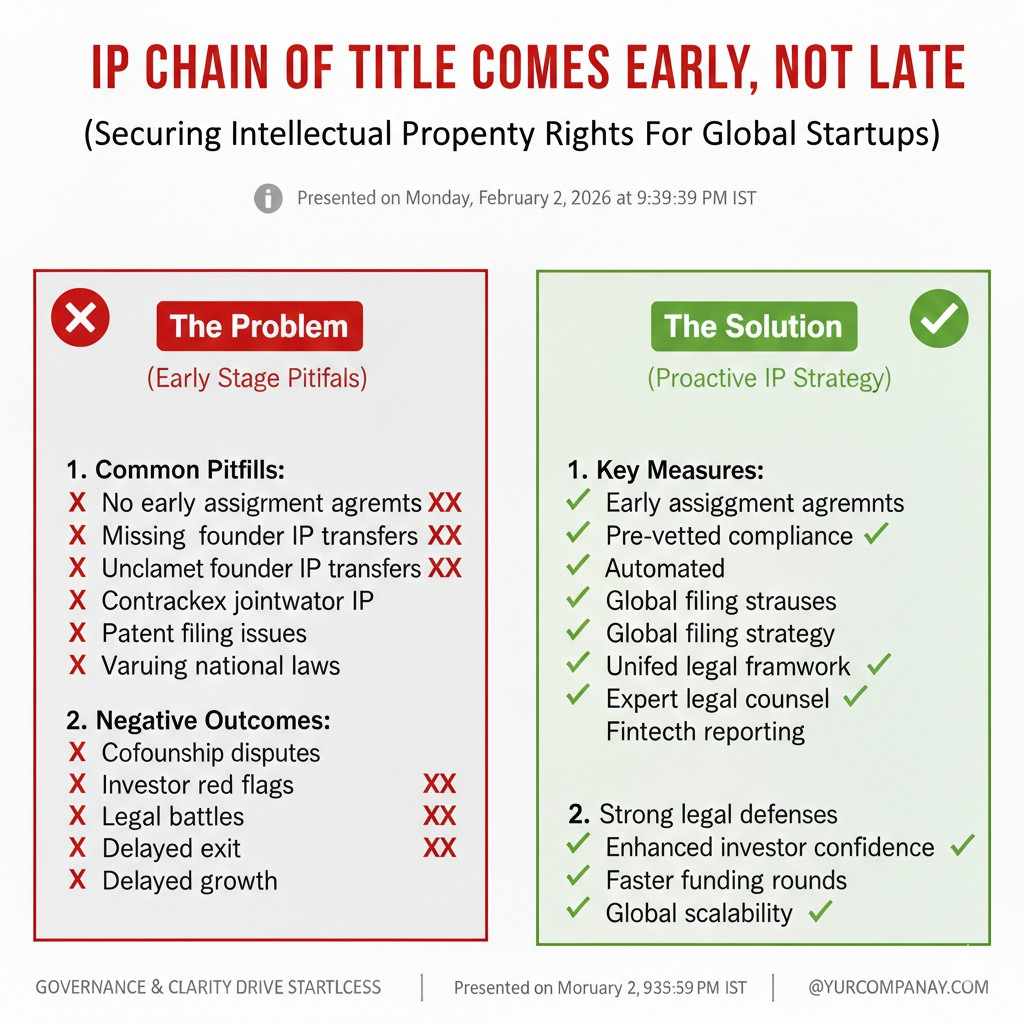

IP Chain of Title Comes Early, Not Late

IP chain of title means one thing: the company owns the inventions it claims to own. Investors want this early because if it is broken, the deal may not be fixable on a tight timeline. This is especially true when the work was done by contractors, or by employees outside the company’s home country.

If you plan to file patents, the chain must be clean before filings as well. Otherwise you risk filing in a way that creates disputes later. For robotics and AI, this is not a “nice to have.” It is the core asset you are raising on.

Employment and Contractor Paperwork Across Borders

In many countries, default ownership rules differ. Some places are more favorable to the employer. Others require very specific clauses to transfer invention rights. Investors know this. That is why they ask for employment agreements, contractor agreements, and invention assignment documents.

Founders sometimes try to solve this with quick templates. That can create gaps, because what works in one country may fail in another. The best approach is to get the paperwork right and consistent across the whole team, so diligence questions end quickly.

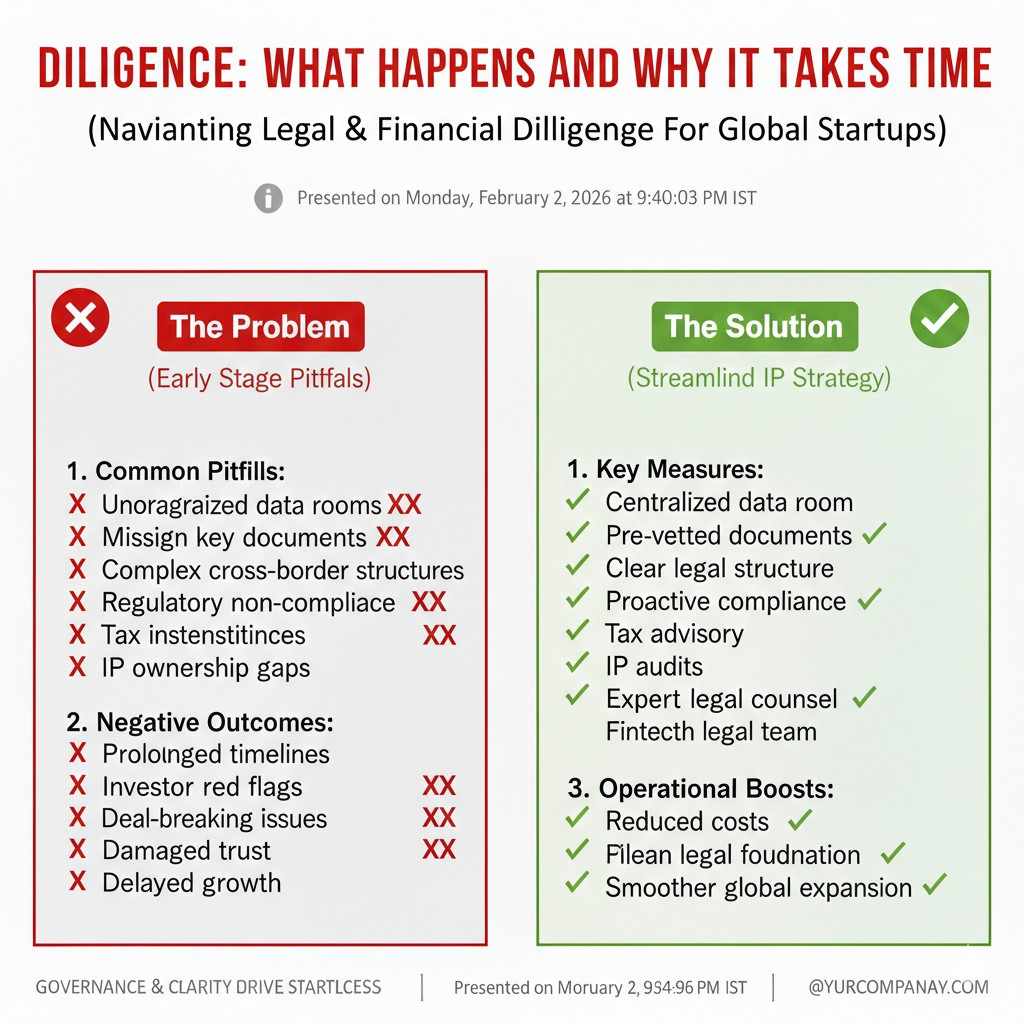

Diligence: What Happens and Why It Takes Time

Diligence Is Structured, Not Personal

Diligence can feel like an interrogation if you are not prepared. But it is mostly a checklist exercise. The investor is trying to confirm facts, and their lawyers are trying to confirm risk boundaries. When you respond quickly and clearly, it becomes calm and routine.

In cross-border rounds, diligence is slower because there are more documents, and because some documents require local context. A US investor may not understand a local employment contract format. A foreign investor may not understand Delaware norms. Your job is to make the story simple for both.

The Data Room Is Your Speed Tool

A good data room reduces back-and-forth. It also prevents version confusion, which is a major hidden cause of delays. If you email documents one by one, someone will open an older copy, comment on it, and waste a day.

You do not need fancy software. You need structure. Clear folder names, clean file names, and one current version of each item. When investors ask for something, you want to send a link, not start searching.

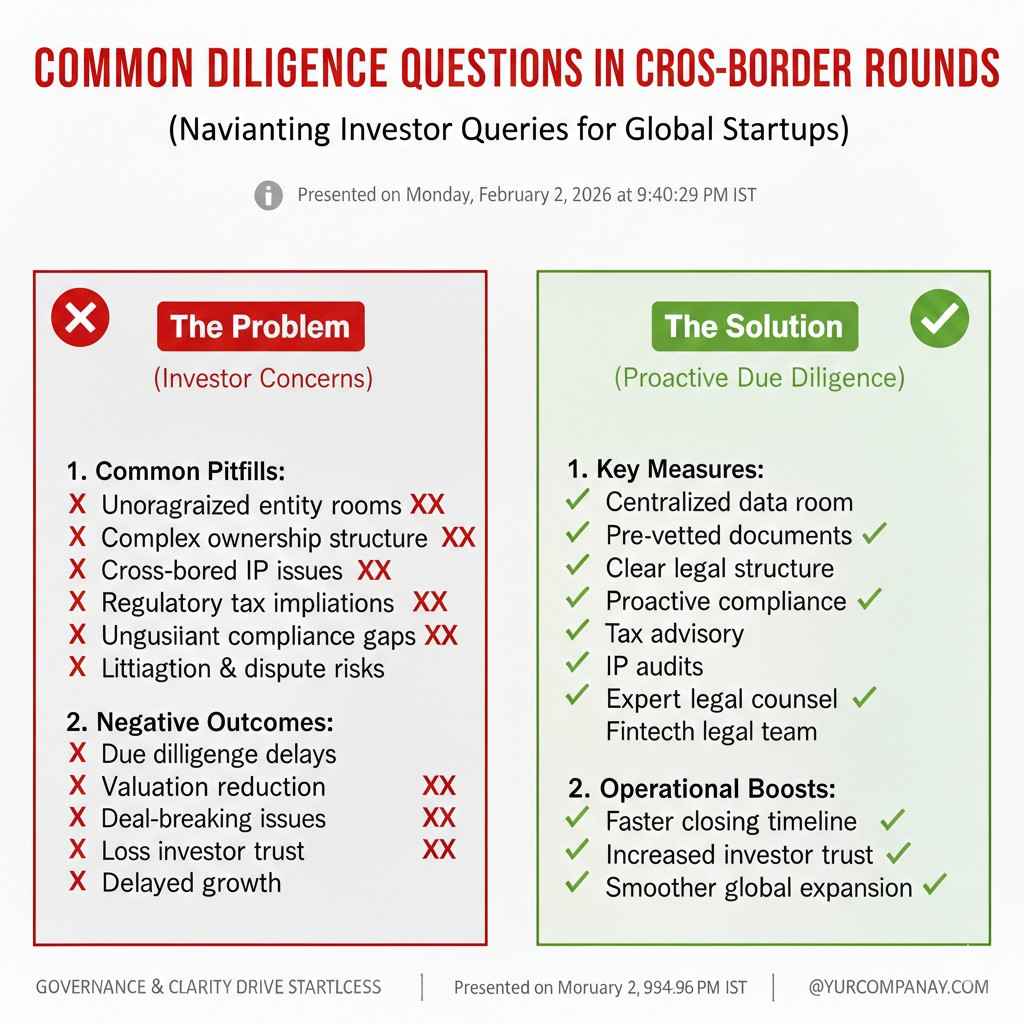

Common Diligence Questions in Cross-Border Rounds

In cross-border closes, investors often ask the same set of questions because they are trying to map legal risk. They ask where the team sits, where IP is created, and how value moves between entities. They ask whether any founders have side obligations in their home countries.

They also ask whether any customer contracts trigger taxes or reporting. They ask whether there are grants, subsidies, or government programs that have conditions. None of this is meant to slow you down. It slows you down only when you have not prepared clean answers.

Drafting and Negotiation: The Middle Weeks

Why Lawyers Take Longer Across Borders

Drafting itself is not the slowest part. The slowest part is aligning assumptions. When a document is drafted under one legal system, but investors operate under another, small phrases create big questions. Lawyers then spend time translating meaning, not just words.

This is why you should expect more redlines than in a purely local round. It does not always mean the investor is being aggressive. Often it means their counsel needs the documents to match their fund rules and their country’s compliance requirements.

The Lead Investor Sets the Pace

If you have a lead investor, their counsel usually drives the document set. That can be helpful because it reduces chaos. It can also create friction if other investors want different templates. In cross-border rounds, smaller investors sometimes request side letters to handle their specific needs.

Your goal as founder is to limit special cases. Every special case adds review time, and review time is the main enemy of a smooth close. You do not want to say yes to every request just to be polite. You want to say yes only when it is truly needed.

Side Letters: Useful but Dangerous

Side letters can solve real issues, like information rights, tax disclosures, or transfer restrictions. But too many side letters create a messy closing binder, and they can create conflicting obligations later.

In a cross-border round, it is better to keep side letters narrow and factual. If an investor wants unusual rights, push those discussions into the main documents or decline them politely. The more custom work you add, the more likely you are to miss your planned closing window.

The Closing Mechanics: Signing Is Not the End

Signatures Happen Fast, Funds Can Be Slow

Many founders think the round closes when everyone signs. In cross-border rounds, signing is only one milestone. The money must clear. Banks must accept wires. Some investors must complete internal approvals after signing before they can release funds.

It is common for wires to take longer than expected because of bank questions. Banks may request invoices, proof of company registration, or confirmation of the purpose of funds. When this happens, founders panic. But it is normal, and it is manageable if you prepared.

Banking Readiness Before You Ask for Wires

A simple way to avoid delays is to ensure your bank account is ready to receive international funds. This includes having clean beneficiary details, matching company names, and a bank contact who can respond quickly.

Cross-border wires fail for basic reasons. A missing middle name. A company address that differs from what the bank has on file. A mismatch between the legal entity name and the operating brand name. These issues can waste days. You want to catch them before investors send money.

Compliance Checks and KYC Requests

Investors, especially institutional ones, must run anti-money-laundering checks and know-your-customer checks. This is not personal, and it is not optional. They may ask for passports, proof of address, and corporate records. If you respond slowly, their compliance queue moves on to other deals.

Some countries also require extra filings when foreign money enters. Whether this applies depends on your jurisdiction and your structure. The key is to know early if any filings are needed, so you can schedule them rather than discover them mid-close.

The Document Set: What You Will Actually Need

Core Deal Documents

Every round has a core set of documents that define the investment. The exact names vary by structure, but the purpose is the same: it states what the investor gets, what the company promises, and what rules apply after the money comes in.

In cross-border rounds, the core documents are often paired with extra schedules and disclosure lists. These schedules feel tedious, but they are where many investors get comfort. If you keep them accurate and clear, redlines drop.

Company Records Investors Always Ask For

Investors want proof that the company exists and that it can legally issue shares or accept investment. This typically includes formation documents, current bylaws or equivalent governance papers, and board approvals that authorize the round.

If you have subsidiaries, investors will want the same records for those entities, plus proof of ownership links. Founders sometimes try to hide complexity, thinking it will scare investors. It usually creates the opposite effect. Clear transparency creates trust.

IP Documents That Matter Most

For robotics and AI, investors want clear invention assignment and evidence that the company owns core work. If patents exist, they want copies and filing details. If patents do not exist, they often want to understand the plan and whether public disclosures have already happened.

This is where Tran.vc can be a strong partner. We invest up to $50,000 in in-kind patent and IP services so your IP story is not a slide. It is an asset you can show. If you want help making your IP investor-ready, apply here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Cross-Border Extras That Show Up Late

This is the category that causes the most delays because founders do not expect it. Tax forms, residency forms, investor declarations, and foreign investment notices often arrive near the end, when everyone thinks the deal is done.

The solution is to anticipate these items as early as possible. If you know you have investors from certain countries, you can prepare the likely forms and details in advance. The close becomes boring, which is exactly what you want.