CE marking can feel like a “Europe-only sticker.” For robotics teams, it is not a sticker. It is a launch gate.

If you build a robot and you want to sell it, ship it, lease it, or even put it into service in the European Economic Area, you need to know one thing early: CE marking is proof that your product meets EU safety, health, and environmental rules that apply to it. It is how you show you did the work, kept the records, and can stand behind the design.

And here is the part many teams learn too late: CE work is not something you “do at the end.” For robotics, the big costs show up when you have to redo hardware, rewrite safety logic, change guards, swap sensors, or rebuild your user docs. If you plan for CE from day one, you can avoid painful rework and ship faster with fewer surprises.

This matters even more for early-stage robotics and AI startups. You are moving fast. You are trying to get pilots. You are trying to hit revenue. You do not want a last-minute blocker that forces a redesign right when a customer is ready to buy.

At Tran.vc, we help technical founders protect the core of what makes their robot different. That includes patents and IP strategy, but it also includes building the right “foundation” so you can sell with confidence. If you are building robotics or AI and you want support early, you can apply anytime here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

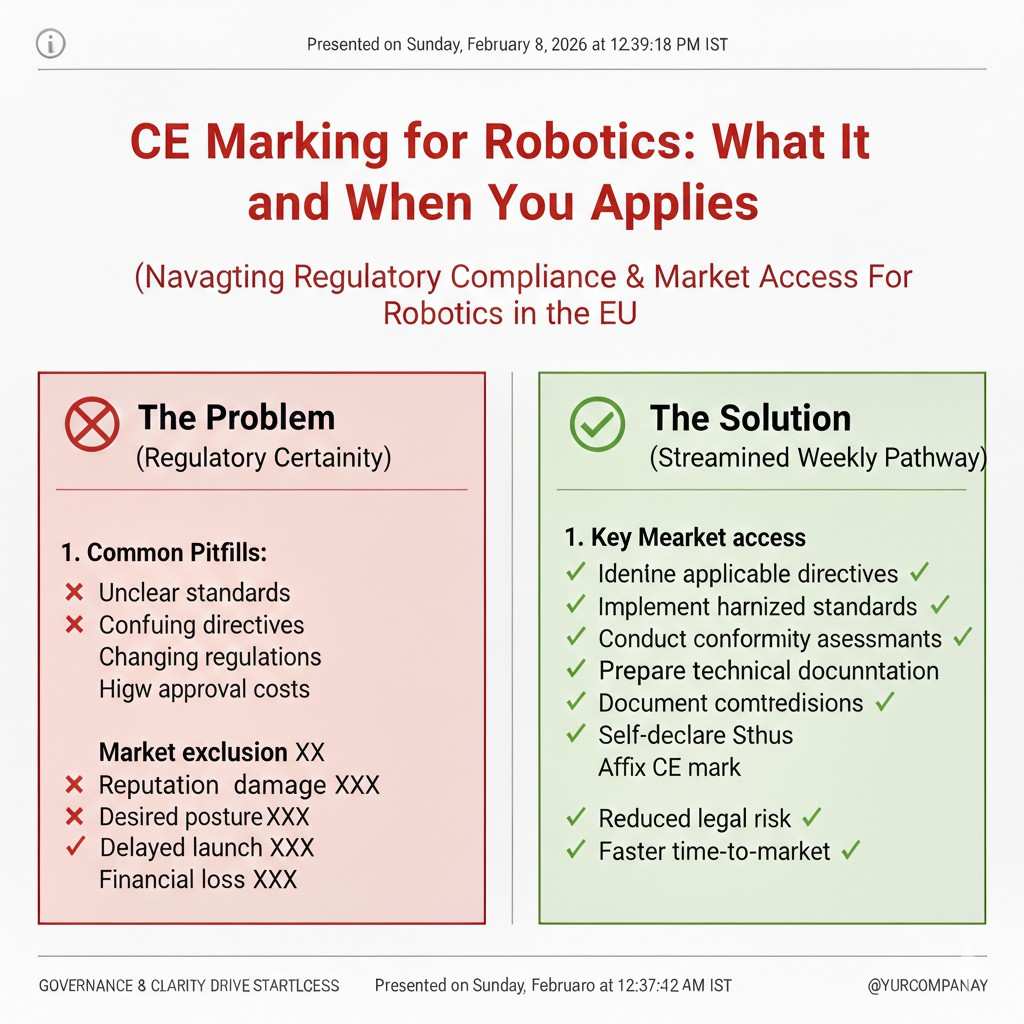

CE Marking for Robotics: What It Means and When It Applies

A quick, clear way to think about CE marking

CE marking is the way the European Union asks one simple question: “Is this product safe enough to be sold and used here?”

When you place a CE mark on a robot, you are saying you checked the right rules, you met them, and you can prove it with real files and test results. You are also saying you will keep that proof ready if a regulator or customer asks.

For robotics teams, the CE mark is not only about one rule. It is usually about a set of rules that overlap. That overlap is what surprises teams who treat compliance like a final checklist.

Why robotics teams get tripped up

Robots are a mix of moving parts, power, sensors, software, and human contact. That creates many safety paths at the same time.

A cobot arm on a shop floor has crush risks, pinch risks, and risks from bad software states. A mobile robot has battery risks, speed risks, and risks from navigation errors near people.

Because robots “act” in the real world, the CE process cares a lot about how the robot behaves in normal use and also in misuse that is easy to predict.

What “placing on the market” really means

A lot of founders think CE marking is only needed when a unit is sold. In the EU, it is broader than that.

If you supply a robot for use in the EU, even if you call it a rental, a lease, or a paid pilot, it may count as placing it on the market or putting it into service. That is often when CE rules start to apply.

So the key is not the label you use. The key is what the robot is doing, where it is being used, and who is responsible for safety.

Why this matters for your sales cycle

EU customers, especially factories and large operators, often ask about CE early. They may ask for your Declaration of Conformity, your risk assessment approach, and your safety design choices.

If you cannot answer with confidence, deals slow down. If your answers sound unsure, buyers may choose a competitor even if your robot is better.

Getting CE-ready thinking into your product plan can help you close faster, because you will sound like a company that can be trusted.

Where Tran.vc fits in early

Compliance and IP are not the same thing, but they are connected in a practical way. When you document your design choices, safety logic, and unique control methods, you often uncover what is truly novel.

That is the kind of clarity that helps with patents and also helps with customer trust. Tran.vc supports robotics and AI startups with up to $50,000 in in-kind patent and IP services, built for early-stage teams.

If you are building a robot and want a strong foundation early, you can apply anytime here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

What CE marking really means for a robot

CE is a legal claim, not a marketing badge

A CE mark on a robot is a legal statement made by the manufacturer. It says the robot meets the EU rules that apply, and that the maker has the technical file to prove it.

In simple terms, you are telling the market: “We designed this safely, we tested what needed testing, and we have the documents that show it.”

This also means your company name is attached to the claim. If something goes wrong, the trail leads back to your design, your files, and your decisions.

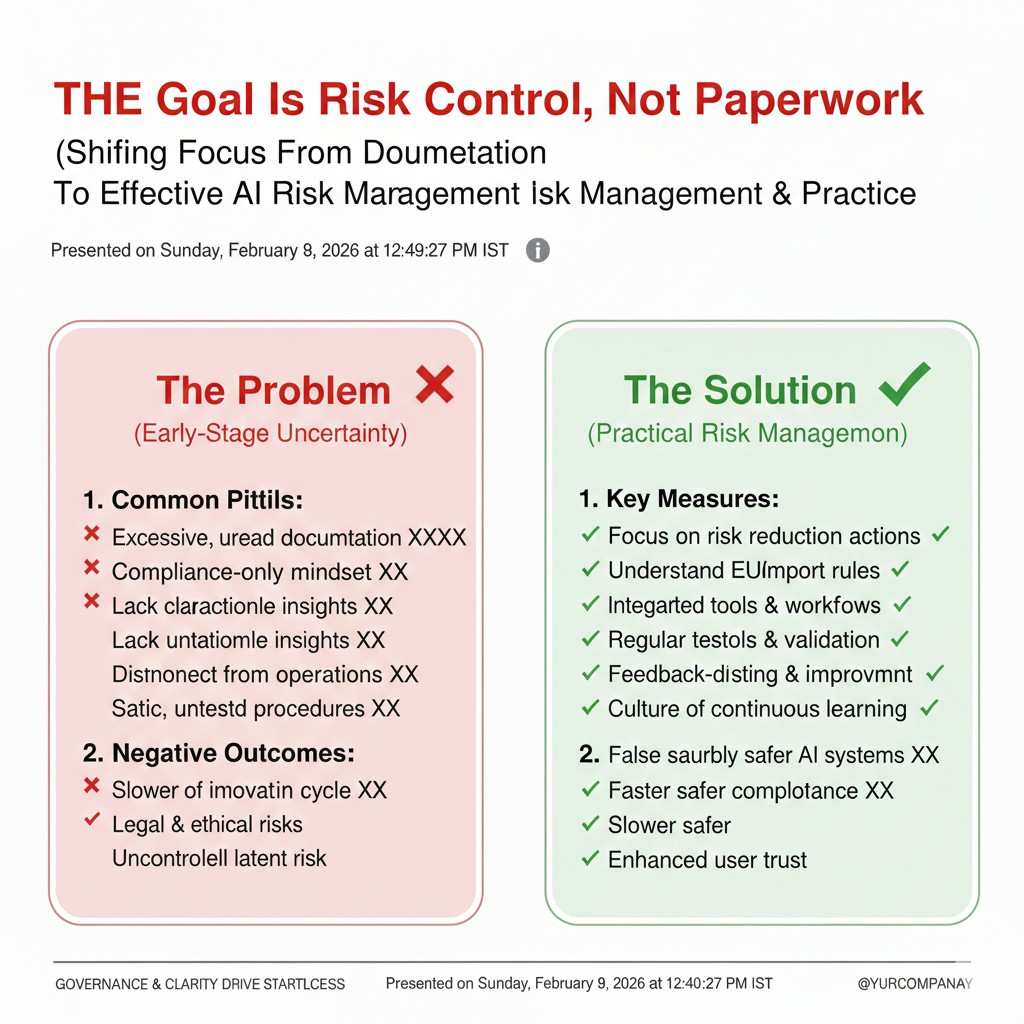

The goal is risk control, not paperwork

People often picture CE as piles of documents. But the heart of CE is not paper. The heart is risk control.

The rules want you to find hazards, judge how bad they can be, and reduce them in a smart order. First you change the design. Then you add guards and safety functions. Only after that do you lean on warnings and training.

If you try to “document your way out,” you usually lose. Robotics is too physical for that. Safety has to be built into the machine and the software.

The technical file is your proof folder

The technical file is where you keep the evidence that you did the work. It is not always submitted to an authority, but it must be ready if you are asked.

For robotics, this file often includes design drawings, safety logic notes, test reports, a risk assessment, and user manuals. It can also include software notes, because software is a key part of how hazards are controlled.

A good technical file is not a burden. It is an asset. It makes audits easier, helps you train new engineers, and supports trust in large sales.

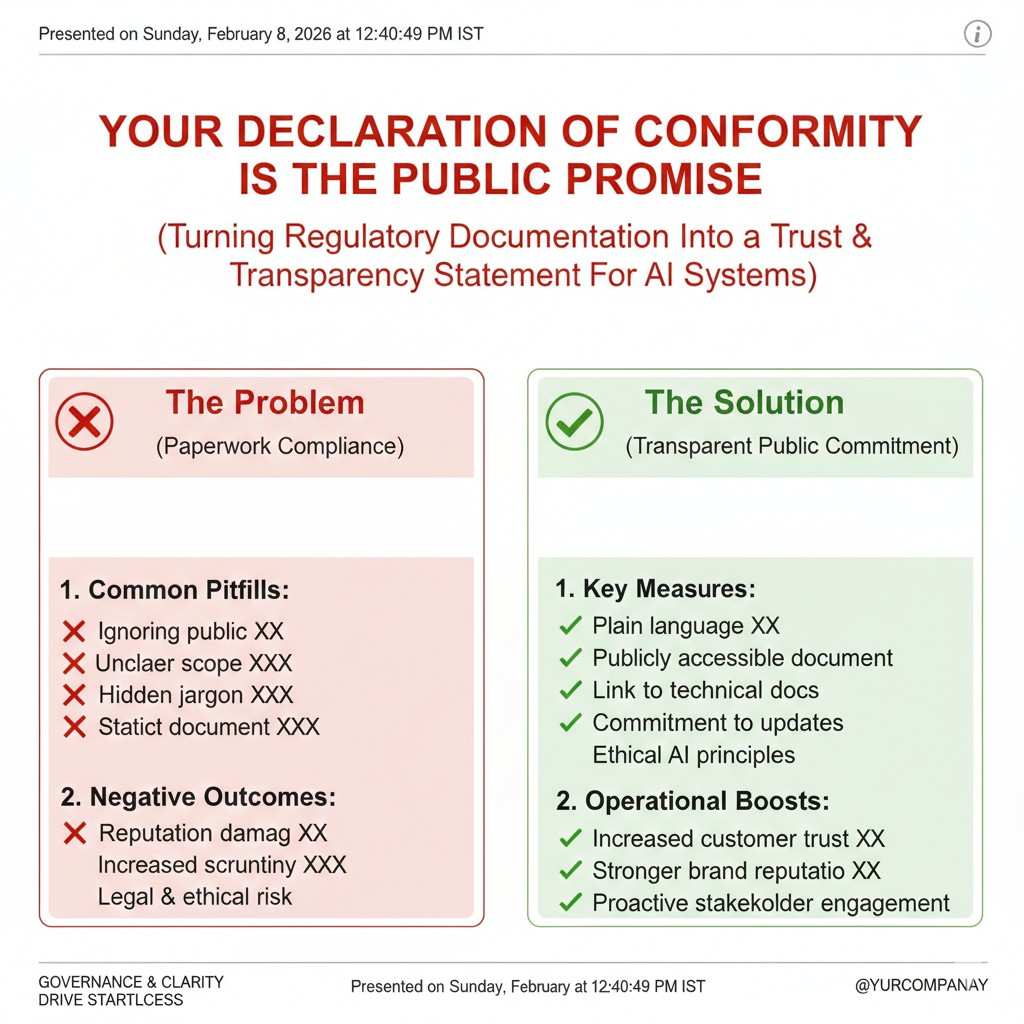

Your Declaration of Conformity is the public promise

The Declaration of Conformity is the signed statement that names the rules you complied with. It is a short document, but it carries weight.

When a customer asks, this is one of the first documents they want. If you hesitate or you list the wrong rules, you lose confidence quickly.

Treat this as a contract with the market. If you sign it, be sure your file can support it.

One robot can trigger several EU rules

Robotics is rarely covered by a single rule set. A robot can fall under machinery safety rules, electrical safety, electromagnetic rules, radio rules, and sometimes more.

This is why CE feels complex. The real job is to map your product to the right set of rules, then plan safety and tests in the correct order.

A good way to stay sane is to treat CE like system design. You identify the “top rules,” then you break down into design controls that satisfy them.

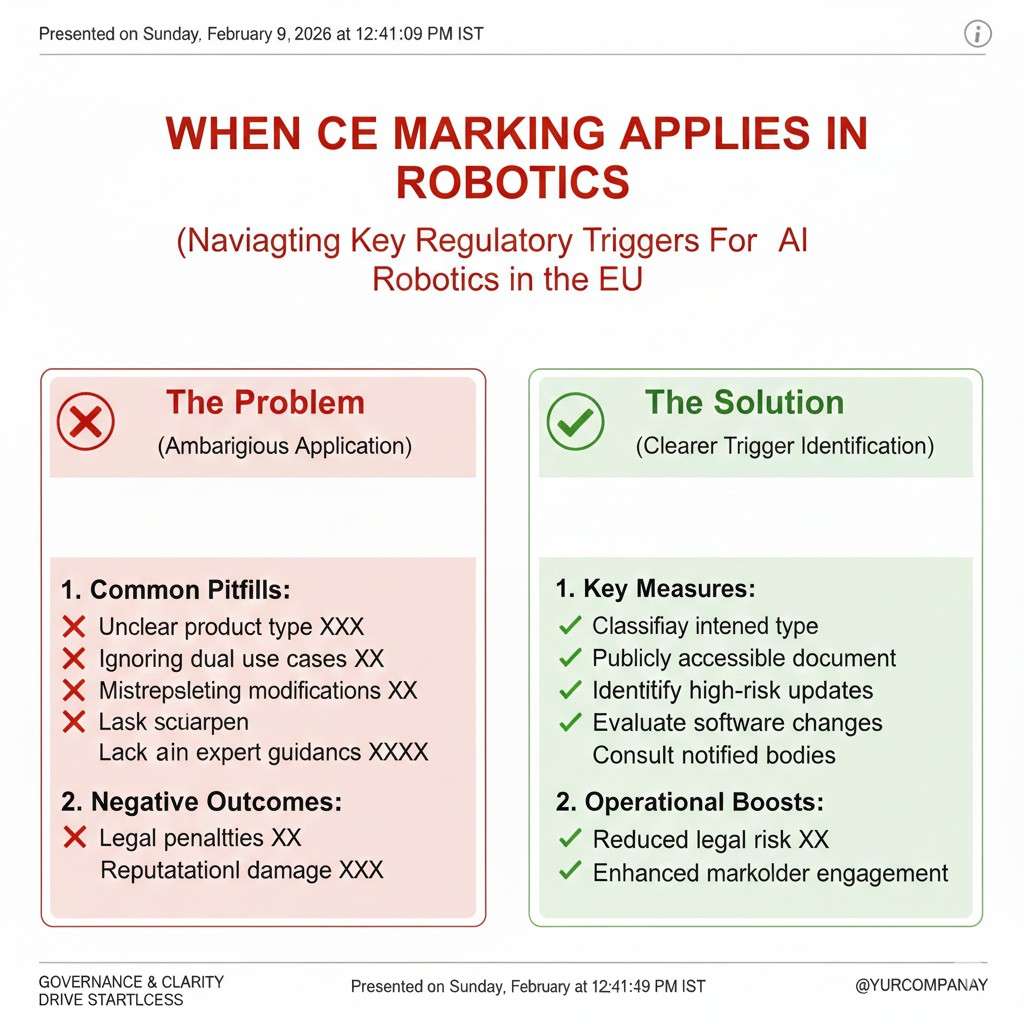

When CE marking applies in robotics

The moment the robot enters EU use

CE marking matters when a robot is made available in the EU market or put into service in the EU. That can include selling, leasing, or even supplying as part of a service model.

If you ship a robot to an EU site and the customer can use it, that is usually the key moment. The fact that you call it a “pilot” does not always change the legal view.

This is why founders should plan early. It is easier to design for compliance than to retrofit once you have installed units.

Selling hardware versus selling a service

Some teams believe that if they sell “robotics-as-a-service,” CE marking is not needed. This is a risky assumption.

If you provide the robot as part of the service and the robot is used in the EU, the equipment still needs to meet the rules that apply to it. The business model does not remove safety duties.

You may also carry more responsibility, because you stay involved in operation, maintenance, and updates.

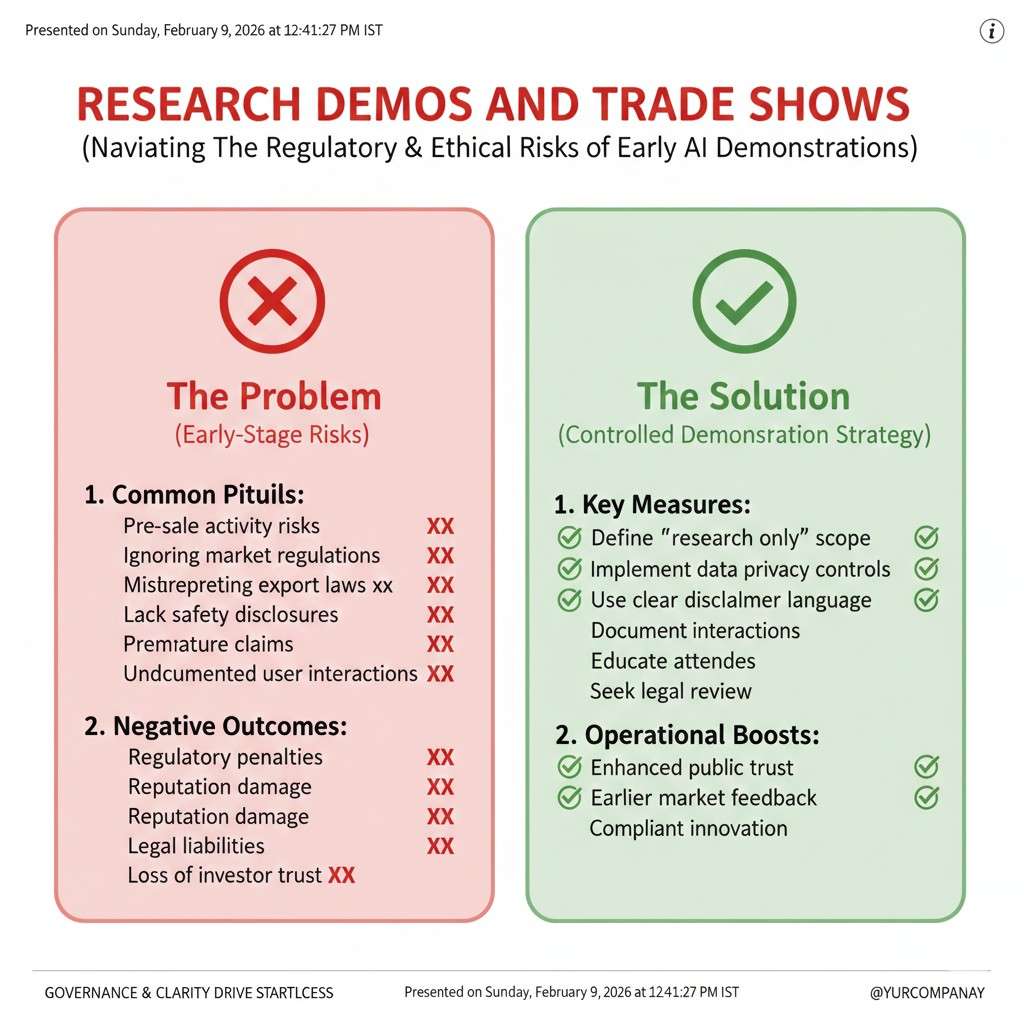

Research demos and trade shows

Teams sometimes bring early robots to EU events to show capabilities. If the robot is only shown and not supplied for use, the situation may be different than a sale.

But the line can blur fast. If a demo unit is given to a partner to try on-site, or left for a period of use, it can start to look like putting into service.

The safe approach is to treat any EU deployment as a compliance moment, unless you have clear guidance that says otherwise.

Components, modules, and subsystems

If you sell a robotic arm, a gripper, or a mobile base as a component, you still may have obligations. The customer may integrate it into a larger machine, but your part can still carry its own safety requirements.

This matters because many robotics startups begin as a module company, not a full system. The “boundary” of your product affects which documents you must supply, and what claims you must avoid.

A clear boundary also helps your patents. It makes it easier to define what you own and what you are protecting.

Software updates can change compliance

Robots evolve through software. Navigation updates, safety zone updates, new AI models, and speed changes can alter how risks behave.

If an update changes safety behavior, you may need to re-check your risk assessment and tests. In some cases, the change is small. In other cases, it is a meaningful new risk.

This is why compliance and product management should talk. Your release process should flag updates that touch safety functions.

The main EU rule families you will hear about

Machinery rules and robot safety basics

Most robots that move and can cause physical harm tend to link back to machinery safety rules. These rules focus on hazards like crushing, impact, cutting, trapping, and unexpected start.

They push you to think about guarding, safe stop, emergency stop, speed limits, safe distances, and safe maintenance.

For a robotics team, this is the “spine” of the CE story. Even when other rules apply, machinery-style risk thinking is often central.

Electrical safety and power risks

Robots are electrical systems. They can shock, burn, overheat, or fail in unsafe ways if power design is weak.

This area looks at wiring, insulation, grounding, power supplies, and how faults behave. It also looks at how maintenance is done safely.

If your robot uses high voltage, fast chargers, or industrial power setups, this becomes even more important.

EMC and why your robot must not misbehave near other gear

EMC is about electromagnetic compatibility. In simple terms, your robot should not cause interference that breaks other equipment, and it should not fail when other equipment is nearby.

Industrial sites can be noisy. Motors, welders, and big drives can create harsh conditions. If your robot resets or drifts because of interference, you can create a real safety hazard.

So EMC is not “just a lab test.” It is a real-world reliability and safety concern.

Radio rules for wireless robots

If your robot uses Wi-Fi, cellular, Bluetooth, or any radio, there are radio rules that can apply. This includes things like proper use of radio spectrum and basic safety and EMC needs.

Many mobile robots and fleet systems rely heavily on wireless links. That means radio compliance can become part of your CE plan even if you do not think of yourself as a radio company.

If you add radio late in development, you may add test and document work late too.

Batteries and charging systems

Battery-powered robots bring their own risks. Batteries can overheat, vent, or catch fire if abused, damaged, or charged in poor conditions.

Charging docks add more scenarios, like exposed contacts, misalignment, and overheating near debris. If your robot works in warehouses, you also have dust, impacts, and rough handling.

These risks often need both design controls and clear user guidance, because misuse is easy to predict in real operations.

A practical way to decide if your robot needs CE

Start with the robot’s purpose and where it will be used

The fastest way to know what applies is to describe the robot in plain words. What does it do, where does it move, what does it touch, and who is around it?

A robot that works behind a fence in a factory is a different safety story than a robot that drives in open areas near staff. A surgical robot is different from a farm robot.

The moment you write this down clearly, you can map hazards more cleanly. It also helps you write better product claims and avoid risky marketing statements.

Define the “product boundary” early

What is included in your product? The robot base, the arm, the end tool, the dock, the cloud system, the app, the safety scanner, the fleet manager?

You want a clean answer because compliance work follows the boundary. If you say the cloud is part of safe operation, then cloud behavior matters for safety claims.

This is also where many AI robotics teams get stuck. If AI output changes motion, and motion affects safety, you cannot treat AI like an optional add-on.

Decide what counts as a safety function

A safety function is any feature that prevents harm or reduces risk. That could be an emergency stop, a safety-rated monitored stop, safe speed control, or a protective field that slows the robot.

In mobile robots, a safety function might be the way the robot detects humans and decides to stop. In cobots, it might be force limits and speed limits that prevent impact injuries.

Once you label these functions, you can design them with the right level of care, testing, and control.

Plan the evidence you will need

Evidence is not only “we tested it once.” Evidence is repeatable tests, clear results, and traceable design choices.

If you know early what evidence is needed, you can build test hooks into software, add sensors for logging, and choose parts that have strong supplier documents.

That saves time later, because you will not be trying to recreate data after the robot is already shipped.

Where IP strategy connects in a real, founder way

Compliance work can reveal your true inventions

When you do risk reviews, you often find what is unique about your approach. Maybe you solved safe navigation in tight spaces. Maybe you built a novel gripper that reduces pinch risk. Maybe you created a better safe stop method.

Those are not just safety notes. They can be patentable ideas if they are new and useful.

Founders often miss these ideas because they only think “patents are for algorithms.” In robotics, a safety mechanism can be one of the strongest inventions.

Documenting design choices helps patents and funding

Investors like to see that you are building a company, not only a prototype. A clear technical file, clear safety approach, and clear IP plan make you look mature.

This does not mean you need a massive process. It means you need a simple habit of writing down what you built, why you built it, and what problem it solved.

Tran.vc helps technical founders do this in a way that creates real IP assets. If you want to explore that support, you can apply anytime here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

The CE marking workflow for robotics teams

Think of CE as a project plan, not a final task

Most delays happen when CE work is treated like a last-mile formality. In robotics, the hardest parts are usually physical changes, not signatures.

A smarter approach is to run CE work like any other engineering track. You start early, you set a scope, you assign owners, and you review progress at fixed points.

If you do this, CE stops being scary. It becomes a steady stream of small decisions that keep you on track.

Step one is mapping your robot to the right rules

Your first practical job is to map your product to the EU rules that apply. This is not just a legal exercise. It changes design priorities.

If your robot is considered machinery, then your hazard controls and safety functions become central. If you have wireless, radio rules enter. If you have a battery system, battery risks enter.

When teams skip this step, they often test the wrong things, write the wrong statements, and discover gaps after money has been spent.

Step two is identifying hazards in a real-world way

A hazard is anything that can cause harm. For robots, hazards can come from motion, heat, electricity, sharp edges, stored energy, and software faults.

It helps to walk through the full life of the robot. Think about shipping, installation, normal use, cleaning, maintenance, and repair. Many injuries happen during “non-normal” moments, like fixing a jam or swapping a tool.

Also think about predictable misuse. A warehouse worker might step into a robot path to grab a fallen box. A technician might bypass a guard to speed up a task. If it is easy to imagine, it should be considered.

Step three is judging risk, not guessing

Risk is often seen as a vague word. For CE work, it is more concrete. You look at how bad the harm could be, how often exposure happens, and how likely the harm is.

For example, a slow indoor delivery robot that weighs little is one story. A heavy mobile robot that moves fast near people is a different story.

When you rate risks honestly, you can decide where to invest. You can focus engineering time on the hazards that truly matter.

Step four is reducing risk in the right order

This order matters because regulators and customers expect it.

First, you reduce risk by design. That can mean rounding edges, limiting force, lowering speed, improving stability, or changing geometry so trapping is less likely.

Second, you add protective measures. That can mean guards, covers, interlocks, safety scanners, safety-rated controllers, or safe stop systems.

Third, you use information for use, like warnings, labels, and training. These are still important, but they are not meant to carry the main safety load.

Step five is using standards to make choices easier

Standards are not just “nice to have.” In many cases, they are the practical guide to what “good” looks like.

When you follow the right harmonized standards, you get a clearer path to compliance. You also get fewer debates with customers, because standards are widely understood in industry.

Robotics founders should treat standards like engineering references. They help you avoid reinventing safety choices and they reduce the chance you miss a key test.

Step six is building the technical file as you go

The technical file is easiest when it grows naturally with the product. If you wait until the end, you will scramble to recreate old design states.

A strong approach is to tie your file to your version control and your release process. When a safety feature changes, you update the risk notes and test evidence in the same sprint.

This way, the file becomes a living record. It also becomes a training tool when you onboard new team members.

Step seven is creating the user instructions that match reality

Instructions are not fluff. In CE work, your manual and safety notes must match how the robot is actually meant to be used.

If your robot needs a clear zone for safe operation, the manual must say it, with clear setup guidance. If you require PPE in a certain step, it must be stated clearly.

Many startups fail here by copying generic manuals. Customers notice quickly. Regulators also notice when instructions look like templates.

Step eight is final checks, then signing the Declaration

When the design, tests, and documents line up, you sign the Declaration of Conformity. This is the moment you publicly claim compliance.

Before signing, teams should do a simple internal audit. You verify that each applicable rule is addressed, each test is recorded, and each hazard has a control that is documented.

Then you can place the CE mark in the proper way, with the right product labeling and traceability.

How to do risk assessment in robotics without getting lost

Use scenarios, not abstract theory

Robotics risk work can become too abstract. A faster approach is to use real scenarios.

Picture a worker walking near the robot while carrying a load. Picture a technician reaching into a tool area to remove a jam. Picture a pallet hitting the robot base. Picture a sensor failing in a dusty site.

These stories help you find hazards that a spreadsheet will miss. They also help you decide which controls are truly needed.

Treat software states as safety-critical events

Robots change behavior based on state. Start-up, idle, mission mode, docking, manual mode, teach mode, error mode, recovery mode.

Each state can have different hazards. For example, manual mode might allow motion without full sensor checks. Recovery mode might override certain limits.

A strong risk assessment names these states, then checks what can go wrong in each one. This is where many robotics accidents are born, in edge states that were not fully designed.

Be strict about what the robot does when something fails

Failure behavior is a core safety topic. What happens if a camera is blocked, a LiDAR stops reporting, a wheel encoder drifts, or a gripper sensor glitches?

If your robot continues as normal with missing safety perception, you may have a major gap. If it moves to a safe stop and signals clearly, that is a safer story.

Designing safe failure behavior is often the fastest way to reduce major risks. It also builds trust with buyers, because it shows you planned for reality.