Running payroll in one country is already hard. Doing it across many countries can feel like juggling fire. Every place has its own tax rules, pay slip rules, work laws, and filing dates. One small miss can lead to fines, unhappy teammates, or a blocked bank transfer.

This guide will help you handle multi-country payroll and compliance in a calm, repeatable way—so you can hire great people anywhere without losing sleep.

Before we go deeper: if you’re building robotics, AI, or other deep tech and you want to protect what makes you different early, Tran.vc can help you turn your inventions into real assets through up to $50,000 in in-kind patent and IP services. You can apply any time here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

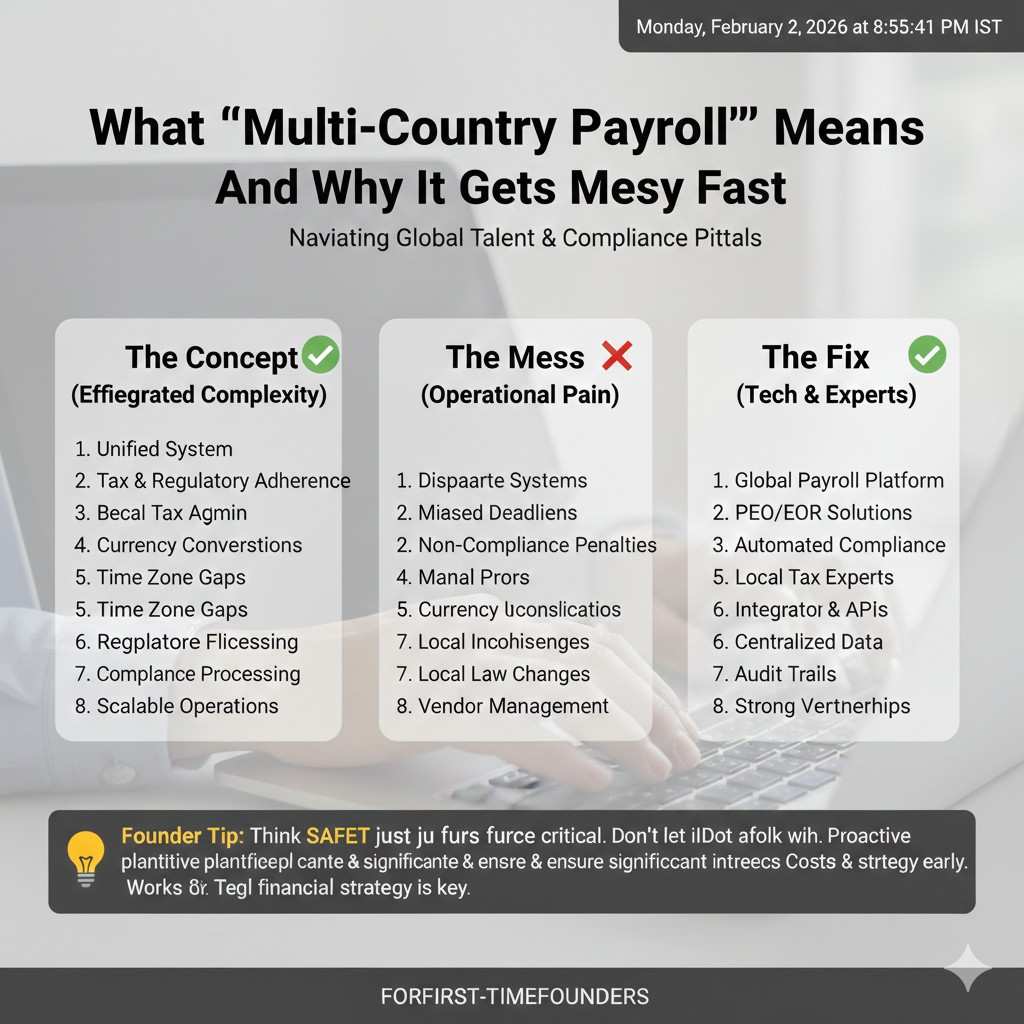

What “multi-country payroll” really means (and why it gets messy fast)

When founders say “we’re paying people in three countries,” they usually mean one of these situations:

You have full-time employees in other countries.

You have contractors abroad.

You use an employer-of-record (EOR) to hire people without opening a local company.

You opened your own local entity in another country and now you must run local payroll.

Each option changes what you must do, what you must file, and who is legally responsible.

Here is the part that surprises many first-time global founders: payroll is not only “sending money.” Payroll is a legal process. It is the formal act of paying wages under local rules, with the right tax taken out, the right benefits provided, and the right reports filed to the right agencies on time.

So the question is not “Can I pay them?”

The real question is “Can I pay them in a way that follows local law every single month?”

If you treat payroll like a bank transfer problem, you will get hurt later. If you treat it like a compliance system, you can scale.

Start with the biggest choice: employee vs contractor vs EOR vs local entity

If you want payroll to stay clean, you need to decide how you are hiring in each country. This decision sets your risk level and your workload.

If you hire a person as an employee in a country where you do not have a local entity, you usually cannot legally put them on your payroll. Many founders try to “figure it out” by paying them as a contractor even though the role is full-time and managed like an employee. That is a common trap.

Misclassification is one of the fastest ways to get into trouble. Authorities care about the reality of the work, not the title on the invoice. If the person has set hours, reports to your manager, uses your tools, does core work for your business, and cannot freely work for others, many countries will say: that’s an employee.

A better way to think about it:

A contractor is a business. An employee is a person inside your business.

If you are treating them like they’re inside your business, plan like they are an employee.

So what are your main paths?

Contractor path: fastest, but high risk if you control them like staff. Also you may still have “permanent establishment” risks depending on what they do, and you can still have IP assignment problems if your contractor agreement is weak.

EOR path: you pay an EOR. The EOR becomes the legal employer in that country. The worker does day-to-day work for you, but payroll, taxes, and local filings are handled by the EOR. This reduces local payroll burden, but costs more and you must manage the relationship carefully. It’s often a good bridge for early-stage startups.

Local entity path: you open a company in that country and run payroll yourself (or through a local provider). This can be best when you have many people there or you need deeper control, but it increases admin work, tax filings, accounting needs, and local rules you must learn.

Many startups mix these. For example, they use an EOR in two countries, contractors in one, and their own entity in another. That is normal. What matters is that you pick deliberately, not by accident.

And before you hire anywhere, handle one more thing early: your invention and code ownership. When you work across borders, IP can get confusing fast. Tran.vc exists to help technical founders lock down patent strategy and IP foundations early—before a funding round forces you to rush. Apply any time: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Build a “country setup sheet” before you pay anyone

Here is a simple move that prevents many problems: for every country where you plan to hire, create a one-page “country setup sheet.” Not a 40-page legal doc. Just one page that answers the key payroll questions.

You want the sheet to cover:

What type of worker are we hiring there (contractor, employee via EOR, employee via our entity)?

What is the currency we will pay in?

What is the pay schedule (monthly, biweekly, etc.)?

What is the standard pay slip content in that country?

What taxes and social payments must be withheld or paid by the employer?

What benefits are required by law?

What key filing dates must we never miss?

Who owns each step (our team, EOR, local payroll provider, local accountant)?

This sheet is less about being perfect and more about making the unknown visible.

In global payroll, what hurts you is not the hard parts you can see. It is the small hidden rule that you didn’t know existed. A setup sheet forces those rules into the open.

Also, this sheet becomes your “handoff doc” when you change payroll vendors later, or when a finance hire joins and needs context fast.

Decide your payroll operating model: one system or many

There are two main ways to run global payroll:

One global platform that supports many countries.

Local providers in each country with your team coordinating.

Early-stage companies usually prefer one platform because it feels simpler. But “one platform” only works if the countries you need are supported well, and if you are comfortable with the platform’s process. In some countries, local providers do a better job with local rules, and global platforms are more generic.

Here’s a practical way to decide:

If you have workers in one or two countries abroad, and you expect changes often, a single platform or EOR often saves time.

If you have a big team in one country, and the rules are complex, a strong local payroll provider plus a local accountant can be more reliable.

Your goal is not perfection. Your goal is repeatable accuracy. You want to run payroll the same way every time, even when you are busy shipping product.

Create your “payroll calendar” and treat it like a product release schedule

Most payroll mistakes happen because of timing, not math.

There are cutoffs for timesheets.

There are dates for salary changes.

There are deadlines for tax filings.

There are bank holidays that shift pay dates.

There are rules about when pay slips must be delivered.

If your payroll calendar lives in someone’s head, you will miss something.

A strong payroll calendar has three layers:

First, the monthly pay run timeline: when inputs are due, when payroll is processed, when money is sent, when pay slips go out.

Second, the compliance filing dates: monthly, quarterly, and annual filings. These vary by country and sometimes by region inside a country.

Third, event-based deadlines: new hire registration, termination steps, bonus runs, equity events, parental leave, sick leave, and benefit enrollments.

The big idea is simple: stop thinking “we run payroll at the end of the month.”

Instead, think “payroll is a cycle with gates.”

When you treat it like a cycle, you can build simple rules like: “No changes after cutoff unless CFO approves.” Even if you don’t have a CFO yet, you can assign that approval to the founder.

Make worker data clean, or payroll will never be clean

Global payroll is a data problem wearing a finance hat.

Every country wants different data fields. Some need tax IDs, national IDs, bank formats, home address formats, and local contract terms. If you collect this data in random emails and chats, you will spend days fixing it later.

Set up a single “source of truth” for worker data. This can be an HR system or even a well-managed sheet early on, but it must be controlled.

For each worker, keep:

Legal name as on official ID

Home address

Tax ID or national ID (as required)

Start date

Worker type and contract type

Pay type (salary, hourly, project)

Currency

Bank details (in the correct format for that country)

Benefits selections

Emergency contact (often required)

Then create a rule: changes to pay, title, location, or working hours must be recorded before payroll cutoff.

This sounds basic. But it is one of the highest leverage things you can do.

Pay slips, contracts, and local language rules: the quiet compliance landmines

Many founders focus only on taxes. Taxes are only one part.

Some countries have strict rules about what must appear on a pay slip, and when it must be given. Some require the pay slip to be in the local language. Some require it to be stored for a certain number of years.

Employment contracts can also have local requirements. For example, some places require that the contract includes specific clauses about working hours, leave, and termination. Others require that a local entity is named in a certain way, or that benefits are described clearly.

If you use an EOR, a lot of this is handled for you. If you run your own entity payroll, make sure your local counsel or local HR expert reviews your standard contract template for that country.

One useful mindset: treat legal documents like code dependencies. If you reuse a template written for the US in a different country, it may compile, but it will crash later.

Taxes and social charges: know what you withhold, and what you owe

In many countries, payroll includes two flows:

Money withheld from the worker’s pay (employee taxes and social payments).

Money paid by the employer on top (employer taxes and social payments).

New global employers often forget the second part. They budget for salary and assume that is the full cost. Then they get a surprise employer bill.

So when you plan a hire in another country, always estimate “fully loaded cost,” not only salary. Fully loaded cost includes employer taxes, required benefits, and any required insurance.

Your payroll provider or EOR should be able to give you an estimate before you hire. If they cannot, that’s a warning sign.

Handling currency, banking, and exchange rate shocks

Cross-border payroll has a money movement layer. If you pay from one bank in one currency to many countries, you can hit issues:

Workers receive less due to bank fees.

Transfers get delayed due to compliance checks.

Exchange rate moves change your monthly burn.

Local bank account formats get rejected.

You can reduce this pain by choosing a standard approach:

Either pay everyone in their local currency and accept that FX is your problem, or pay in one currency and accept that the worker will take FX risk and fees. Many countries and contracts prefer local currency for employees.

Most companies choose to pay employees in local currency. For contractors, you may have more flexibility, but be careful: even for contractors, local rules may expect local currency in certain cases.

If exchange rate swings could matter to your runway, set a simple policy. For example: review FX rates weekly, keep a buffer, and lock larger amounts when needed. You don’t need fancy finance tools at the start, but you do need awareness.

Terminations and offboarding: where compliance gets expensive

If there is one area where founders get blindsided, it is ending employment.

Termination rules vary a lot by country. Some require notice periods. Some require severance. Some require documented performance steps before you can end employment. Some require you to pay out unused leave. Some have strict timelines for final pay.

If you are using an EOR, they will guide you, but they still rely on you for facts and timing. If you run your own entity, you need local help.

A strong practice is this: before you hire your first employee in a new country, learn the basics of termination in that country. Not because you plan to fire people, but because you need to know your obligations.

This changes how you write contracts, how you set probation periods, and how you budget risk.

A founder-friendly workflow that keeps you compliant without drowning

Here is a simple operational rhythm that works well for startups:

At hiring time, do a “country setup sheet” and decide worker type.

Before the first pay run, do a mini audit: contract signed, IDs collected, bank validated, benefits set, payroll provider ready.

Each month, run payroll using a fixed timeline with cutoffs.

Each quarter, do a compliance check: filings done, taxes paid, benefit bills matched, and any law changes noted.

Once a year, do a deeper review: provider performance, cost, error rate, and whether you should switch models (EOR to entity, contractor to employee, etc.).

The main secret is consistency. The more you improvise, the more mistakes happen.

Where startups slip most often (so you can avoid it)

Most global payroll issues come from a few patterns:

Hiring a “contractor” who is really an employee.

Missing local registrations for a new hire.

Not budgeting employer costs on top of salary.

Not tracking country-specific pay slip and filing rules.

Late payroll changes that break the cycle.

Not documenting approvals for pay changes and bonuses.

Poor offboarding steps, leading to disputes or fines.

If you build guardrails around these, you will avoid most pain.

Also, remember that global hiring touches IP. If a worker in another country builds part of your core tech, you want strong invention assignment terms and clear ownership of work product. This is one reason Tran.vc focuses so much on early IP foundations for technical founders. Apply any time: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

How to Handle Multi-Country Payroll and Compliance

Start by picking the right hiring path in each country

Before you build any payroll process, decide how you will legally hire in each country. This sounds basic, but it controls almost everything that comes next. The same person can create very different compliance work depending on whether they are an employee, a contractor, or hired through an EOR.

When you pick the wrong path, you don’t just add admin work. You create legal risk that can show up months later, often at the worst time, like during due diligence or a local audit.

Employee vs contractor: the real test is “control”

Many teams call someone a contractor because it feels simpler. But many countries do not care what you call them. They look at how the work is done. If you set their hours, manage them like staff, and rely on them like a core teammate, they may be treated as an employee.

That is why it’s safer to decide using one question: are you controlling the “how” and “when” of their work, or are you buying an outcome? Buying an outcome fits a contractor. Controlling the work fit is closer to employment.

EOR vs local entity: a choice between speed and long-term control

An EOR is often the cleanest way to hire quickly without opening a local company. The EOR becomes the legal employer, and you manage the person’s day-to-day work. This reduces your local filing burden, but it can cost more and adds another partner you must manage well.

A local entity gives more control and can be cheaper at scale, but it adds accounting, tax filings, and local employer duties. It is often best when you have a growing team in that country and plan to stay long-term.

A practical rule for early-stage founders

If you have one person in a new country and you are still learning, an EOR can reduce mistakes. If you have a cluster of hires planned, a local entity can make sense. If the role is truly project-based and independent, a contractor can work, but only if the reality matches the paperwork.

If you are building deep tech, also remember that worker type impacts IP ownership terms. For robotics and AI teams, locking down invention assignment early is not optional. Tran.vc helps founders do this right from day one. Apply any time: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Build a country-by-country payroll blueprint

Why “one global approach” fails without local detail

A global payroll plan sounds neat, but every country has its own rules on pay cycles, pay slips, taxes, benefits, and filings. If you use the same assumptions everywhere, you will miss a local requirement sooner or later.

The goal is not to memorize every local rule. The goal is to build a simple blueprint per country so your team knows what “good” looks like in that place.

The one-page “country setup sheet” that saves you later

For each country, create a short document that captures what you must do and who does it. Keep it simple, but complete enough that someone else could run payroll if you were out for a week.

Include the worker type you chose, the pay schedule, the required withholdings, employer costs, required benefits, and the key filing deadlines. Also include the names of the partners involved, like the EOR, local payroll firm, and local accountant.

Make ownership clear so tasks don’t fall through gaps

Payroll breaks when everyone thinks someone else is handling a step. Your country sheet should state who owns each action, like collecting worker IDs, registering a new hire, approving payroll, sending funds, and filing reports.

Even if you use an EOR, you still own certain inputs. If you don’t deliver those inputs on time, the EOR cannot fix the delay. Clear owners prevent “silent failures.”

Validate your blueprint before the first pay run

Before you pay the first person in a country, do a quick pre-flight check. Confirm that the contract is signed, bank details are validated, tax forms are complete, and benefits are enrolled where required.

This prevents the most common first-month payroll problem: scrambling to fix missing data while a real person is waiting to be paid.