You have a deep tech idea. It might be a new model, a new robot motion trick, a new sensor setup, or a new way to turn messy data into clean decisions. You also have a big question in the back of your mind: “Can I patent this… or is it just a cool project?”

Let’s make this simple. You do not need to be a lawyer to spot early signals. You just need a clear way to think.

And if you want expert help fast, you can apply anytime here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

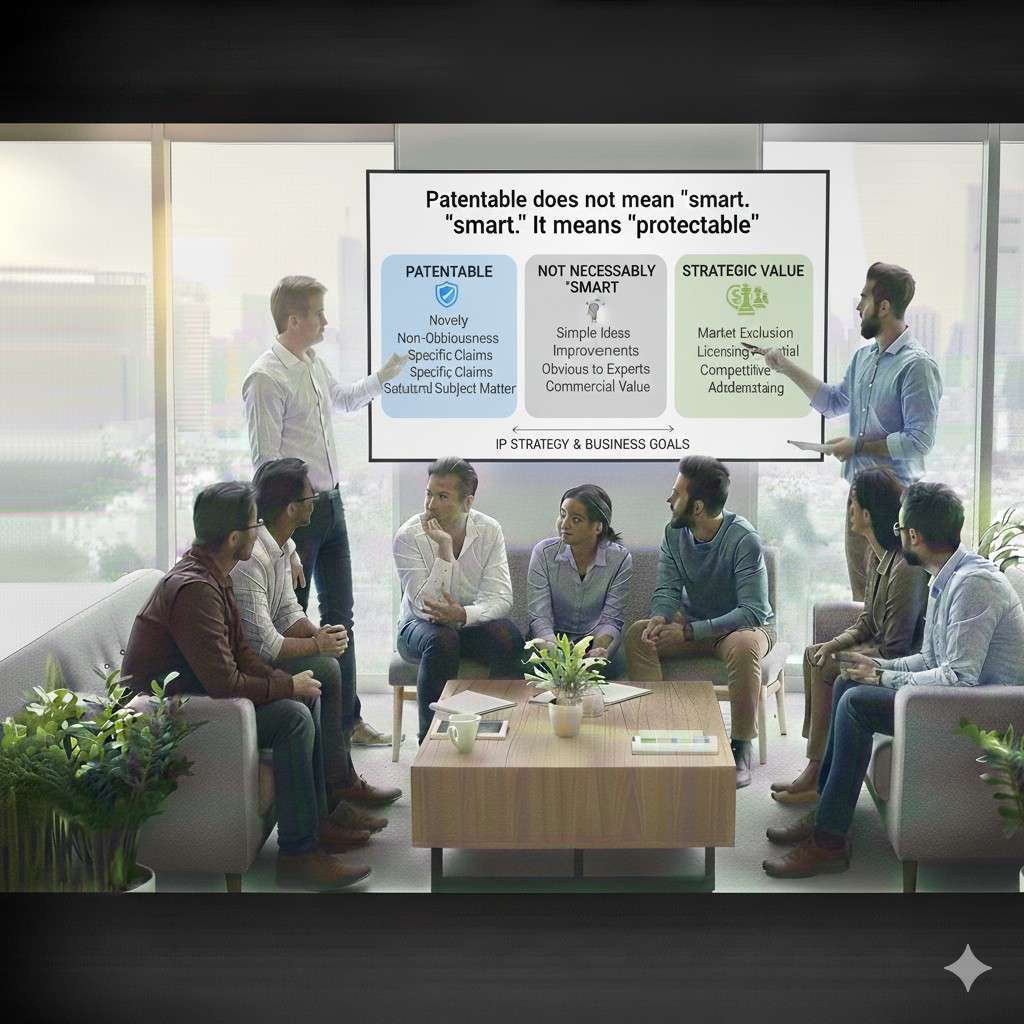

Many founders mix these up.

Your idea can be smart and still not patentable. And sometimes a simple twist is patentable because it is new and specific.

A patent is not a prize for being clever. It is a legal fence around a real method, system, or product. A patent tells the world: “If you do it this way, you are stepping on my land.”

So the first thing to do is stop asking, “Is my idea brilliant?” and start asking, “Can I draw a clean fence line around it?”

If you cannot explain what the fence is, the patent will be weak.

This is why deep tech teams often miss the moment. They focus on the model’s accuracy, the robot’s speed, or the demo video. But patents reward clear structure: what it is, how it works, and what makes it different.

Tran.vc is built for this exact gap. They put up to $50,000 of in-kind IP and patent work behind technical founders so you can turn real engineering into real assets—early. You can apply here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Patentable does not mean “smart.” It means “protectable.”

The key shift in your thinking

Many founders think patents reward brilliance. They do not. Patents reward clear edges.

A patent is not a trophy for a clever idea. It is a legal fence around a specific invention. If someone builds the same thing in the same way, the fence gives you power to stop them or force a deal.

So the right question is not, “Is my work impressive?” The right question is, “Can I draw a clean line around what I built?” If you cannot, the patent will be weak, even if the tech is strong.

Why deep tech teams get this wrong

Deep tech work feels like a bundle. There is code, data, math, hardware, and timing. That bundle can be hard to explain in a short, stable way.

But patents need structure. They need a clear “what it is,” “how it works,” and “why it is different.” When you can tell that story without hand-waving, your odds go up fast.

What “protectable” looks like in real life

A protectable invention usually has steps or parts that you can point to and say, “This is the new piece.” It also has a result that matters, like lower drift, faster inference, less power draw, safer motion, or more stable sensing.

If you can name the new piece and show the result, you are already doing the work a strong patent needs.

Where Tran.vc fits

This is exactly the gap Tran.vc helps close. Tran.vc invests up to $50,000 of in-kind patent and IP work so technical founders can turn real engineering into real assets early.

If you want help shaping your invention into a clear fence line, you can apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Step one: name the “thing” you are trying to protect

Why “a cloud of work” is hard to patent

Most deep tech starts as a messy mix of experiments. You might have a notebook full of tests, three versions of code, and a robot that “kind of works” on the bench.

That is normal. But the patent system does not protect a vibe. It protects an invention that has a stable shape, even while the product keeps improving.

So your first job is to reduce the cloud into one “thing” you can describe.

The one-sentence framing that forces clarity

Try writing one sentence that starts like this: “My invention is a ____ that ____.”

This is not marketing. This is not a pitch. It is an internal tool to force clean thinking.

If you struggle to fill in the blanks without using fuzzy words like “better” or “smart,” that is a sign you need to tighten the invention before you judge patentability.

Turning vague value into concrete mechanics

Instead of saying, “It makes robots safer,” say how it does it. Does it limit force based on real-time contact estimates? Does it predict slip before it happens? Does it slow motion only when a certain sensor pattern appears?

Instead of saying, “It improves accuracy,” say where the gain comes from. Is it a special feature map? A training trick? A new way to handle missing data? A timing step that reduces noise?

When you describe mechanics, you stop sounding like an idea and start sounding like an invention.

A simple way to separate product from invention

Your product may include ten features. Your invention might be just one of them.

A helpful test is to ask: “If I had to protect only one core advantage, what would I pick?” That answer is often your first patent target.

How Tran.vc helps at this stage

Many founders do not need more brainstorming. They need help picking the right “thing” to file first, so the first patent covers the core moat.

Tran.vc helps you shape and select the invention with real patent attorneys and operators, so you do not waste your early filings. Apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

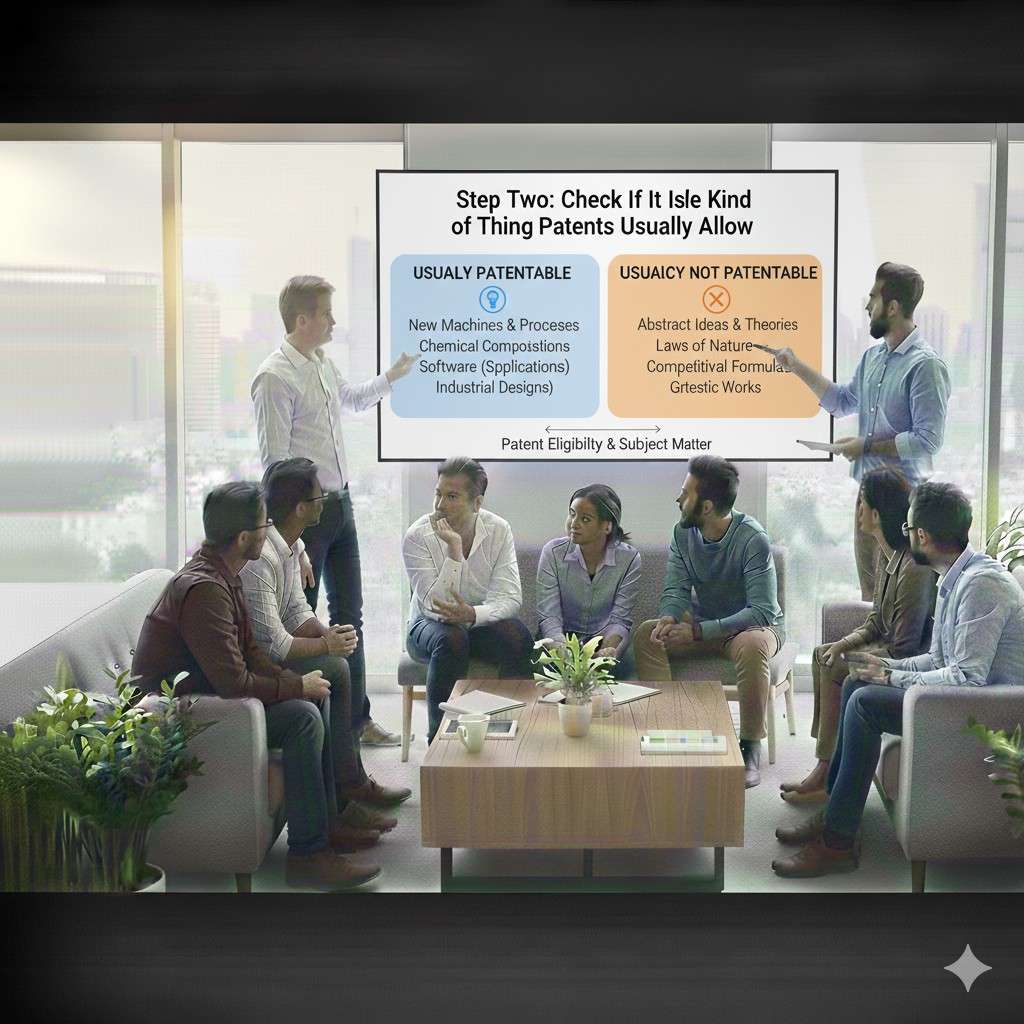

Step two: check if it is the kind of thing patents usually allow

The line between “invention” and “abstract idea”

Patents are meant for useful inventions. But the patent office is strict about one category: abstract ideas.

A pure math rule, a generic “use AI to do X,” or a business plan wrapped in software language can get rejected. That does not mean AI cannot be patented. It means you must show a technical solution, not just a concept.

Why robotics often has an easier path

Robotics inventions often touch the physical world. They change how a machine senses, moves, grips, plans motion, avoids collisions, or manages power.

Because the effect is physical and the steps are concrete, it can be easier to explain what is new and why it matters. A strong robotics patent often reads like a precise recipe for getting a machine to behave in a new way.

How AI becomes patentable in practice

For AI, the safest path is to anchor the invention to a technical problem and a technical fix.

A weak framing is: “a model that predicts defects.” A stronger framing is: “a specific pipeline that detects micro-defects on edge hardware by using a particular pre-step, a specific feature method, and a post-step that cuts noise while keeping speed.”

Notice what changes. The invention becomes a set of steps with technical choices and a clear outcome.

The “remove the computer” test

Ask yourself: “If the computer, sensor, or robot is removed, does my invention still exist in the same way?”

If the answer is “yes,” you may be describing an abstract idea. If the answer is “no, it only works because of these technical parts and limits,” you are closer to patentable ground.

This test is not perfect, but it forces you to be honest about whether you built a technical method or just named a goal.

Common traps deep tech founders fall into

One trap is claiming the result instead of the method. Saying “reduce latency” is not enough. You need to show the concrete steps that reduce latency.

Another trap is being too broad. If your description sounds like it could cover every model in the world, you will face hard pushback. Patents like specific mechanisms, not sweeping ownership of a whole field.

What to do if you are in the “gray zone”

If your idea feels abstract, do not panic. Often the fix is to write the invention in system terms.

Define the inputs, define the steps, define the outputs, and define the limits. Show how the invention behaves under real constraints like compute, memory, power, noise, or safety rules.

That shift can move an “idea” into an “invention.”

Where Tran.vc helps here

This is where founders lose months. They either file something too abstract and get rejected, or they avoid filing at all and lose priority.

Tran.vc helps you frame AI and robotics inventions in a way that fits patent rules while still protecting what matters. Apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

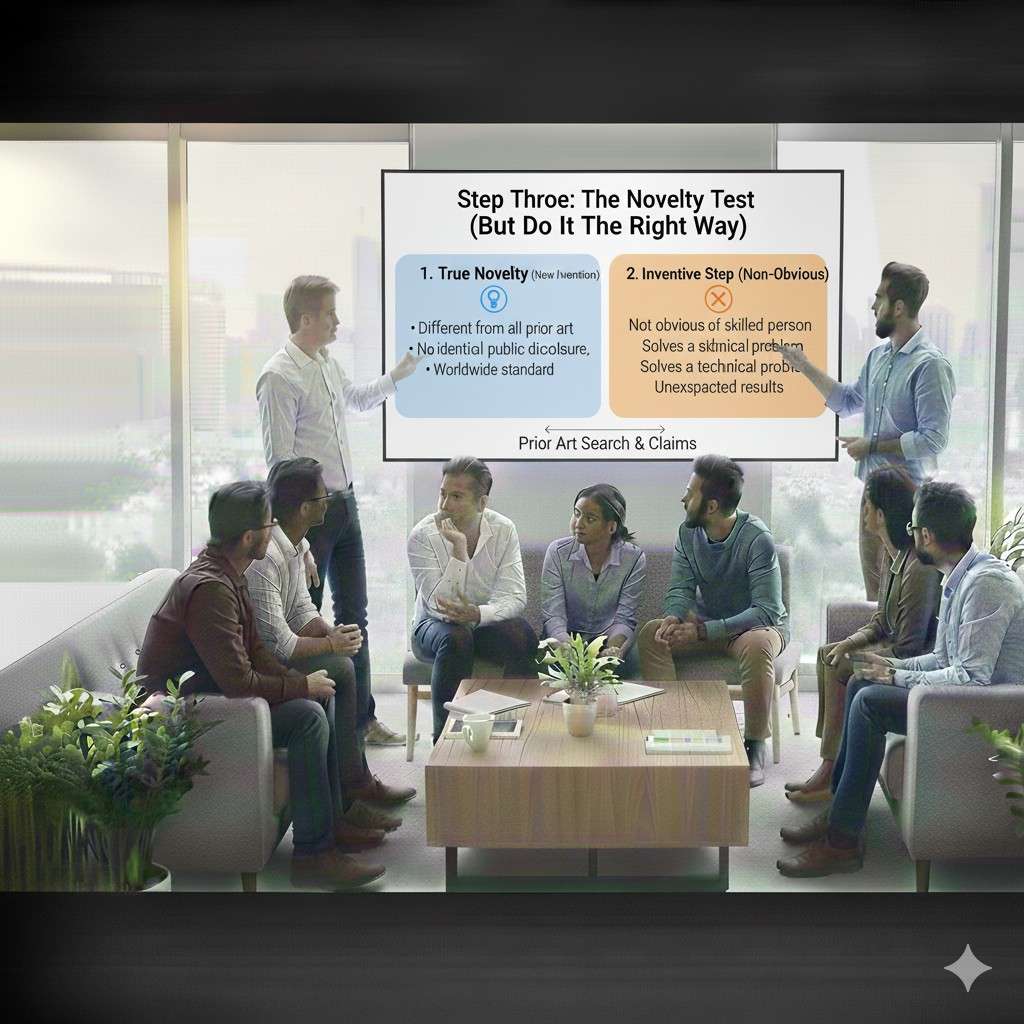

Step three: the novelty test (but do it the right way)

Novelty means “not already public”

Novelty is simple in theory. If the same invention is already public, you cannot patent it.

The tricky part is what counts as “public.” Papers, blog posts, GitHub repos, conference talks, demo videos, product pages, and even some casual posts can count.

So the novelty test is not only about competitors. It is also about you and what you may have already shared.

The practical novelty check you can do today

Start by writing a plain description of your invention in two parts.

First, describe what it does in one paragraph. Second, describe how it does it in another paragraph, using the real steps and parts you built.

Now ask: if a strong engineer in my space read this, would they say, “I have seen this exact approach before,” or would they say, “That combination is new”?

That is the point of the test. You are looking for “same approach,” not “same goal.”

Why deep tech novelty is often hidden

Many deep tech inventions look normal from the outside. Two robots can both pick objects. Two models can both classify defects.

The novelty often lives in details people do not see, like a calibration routine, a data cleaning step, a control loop trick, or a training method that makes the system stable in the real world.

So when you test novelty, zoom in on the “how,” not the headline.

A realistic way to compare yourself to prior work

If you search your space, you will find things that look close. That is normal. Novelty does not require you to be the first person to touch a problem.

It requires that your specific method is not already shown. Many patents are improvements, not brand-new worlds.

Your job is to identify the exact twist you added that changes performance, reliability, cost, safety, or scale.

Avoiding the most common self-sabotage

Founders sometimes assume, “If I can imagine it, it must already exist.” That is often wrong.

Other founders assume, “No one has my exact code, so I am safe.” That is also risky, because patents protect ideas expressed as methods, not your exact file structure.

You want a grounded view, not fear and not overconfidence.

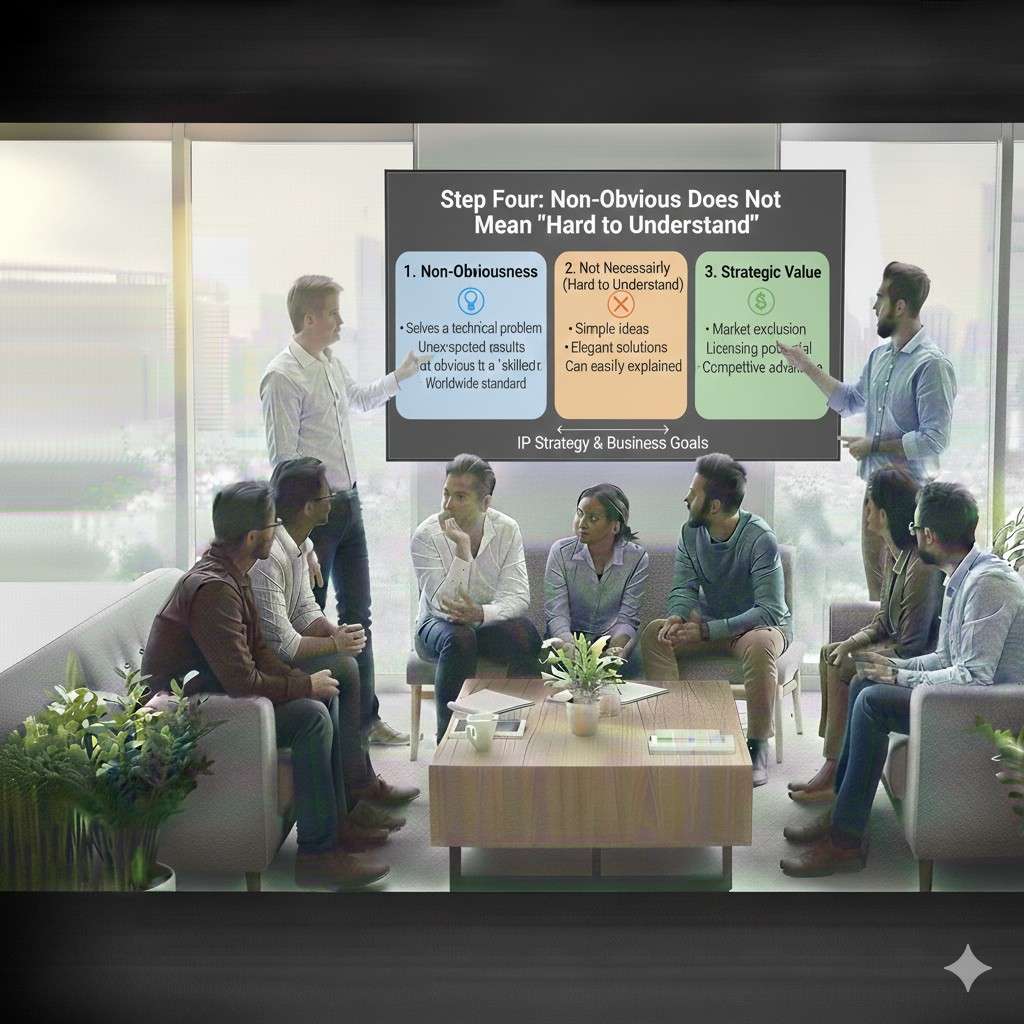

Step four: non-obvious does not mean “hard to understand”

What non-obvious really means

After novelty, the next filter is non-obviousness. This is where many founders get confused.

Non-obvious does not mean complex. It does not mean full of math. It means that someone skilled in your field would not arrive at your solution by simply combining known pieces in an expected way.

A simple change can be non-obvious if it goes against normal thinking in the field or solves a problem people accepted as unavoidable.

Why deep tech teams misjudge this step

Engineers live deep inside their systems. What feels obvious to you after months of work may not be obvious at all to someone else.

You also see all the failed paths. The patent reader does not. They only see the final path and ask, “Would a skilled person naturally do this?”

Your job is to show that the path you chose is not the default one.

A grounded way to test non-obviousness

Ask yourself this question: “Before I built this, would most experts have expected this to work?”

If the honest answer is no, you may have a strong case. Many good patents exist because they break assumptions, not because they add complexity.

Examples include using less data instead of more, slowing a step down to improve stability, or adding a constraint that improves overall performance.

Why “just combining things” is not always obvious

Patent examiners often say, “You just combined known techniques.” That sounds scary, but it is not the end.

Combining known things in a new way can be non-obvious if the combination creates a new effect, fixes a known problem, or goes against how people usually combine them.

The key is explaining why the combination is not routine.

How this shows up in AI and robotics

In AI, non-obviousness often comes from how data is handled, how models are structured under limits, or how outputs are used downstream.

In robotics, it often comes from control logic, safety layers, timing rules, or feedback loops that are not standard practice.

These are not flashy changes, but they are often where the real value lives.

How Tran.vc strengthens this part

This step benefits hugely from experience. Tran.vc works with patent attorneys who understand deep tech and know how to frame non-obviousness without exaggeration.

That framing can be the difference between a strong patent and a fast rejection. You can apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

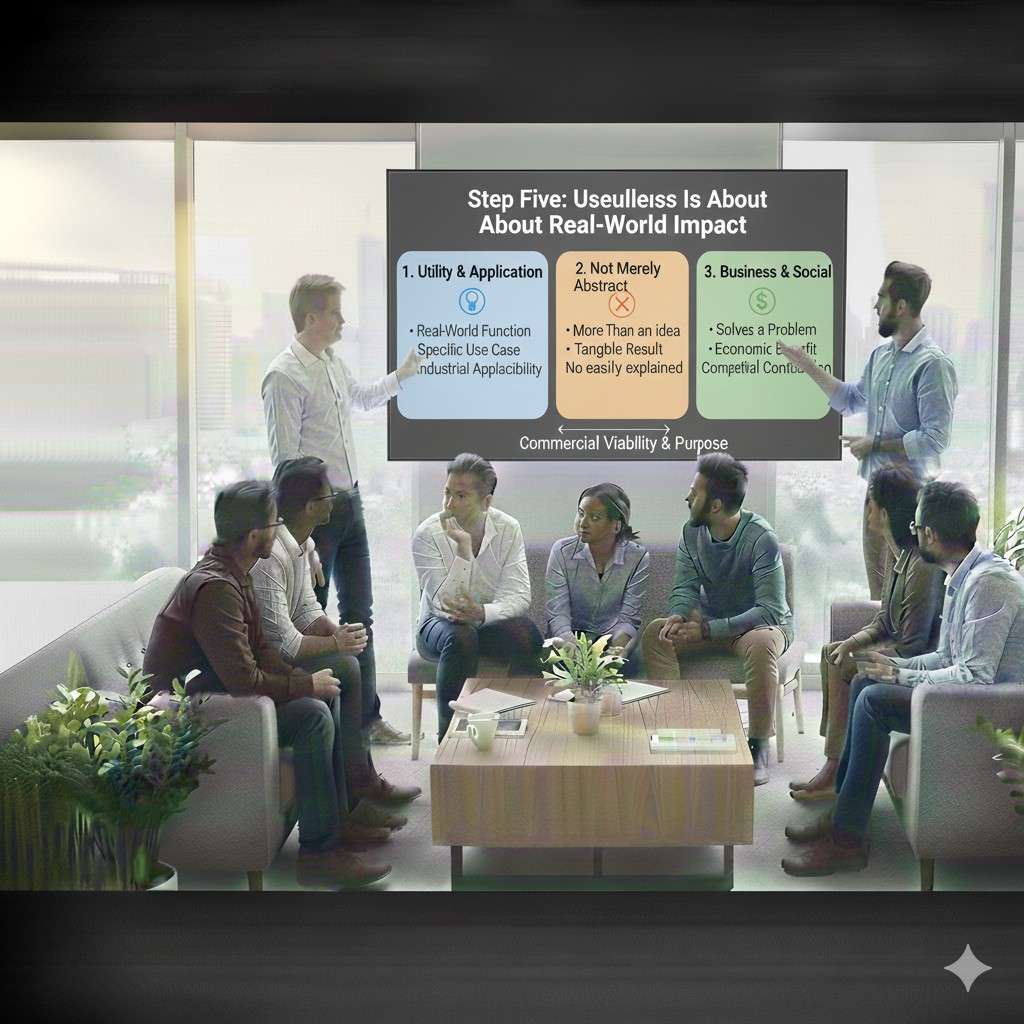

Step five: usefulness is about real-world impact

Why usefulness is usually easy but still important

Usefulness sounds basic. Your invention must do something useful.

Most deep tech inventions pass this without trouble. But you still need to state the use clearly and tie it to the invention.

A patent is not the place to be vague. You want the reader to understand where and why the invention matters.

Connecting function to benefit

Do not just say what the invention does. Say what problem it solves in the real world.

For example, instead of “controls robot motion,” explain that it reduces collisions in tight spaces or extends battery life in mobile robots.

This connection helps the patent stand on solid ground and shows it is not theoretical.

Avoiding over-claiming usefulness

Be careful not to claim benefits you have not validated or reasonably expect.

Overstating results can weaken credibility. Patents do not need perfect numbers. They need believable outcomes based on the described steps.

Clear, honest usefulness is stronger than bold promises.

Step six: enough detail to teach, not to copy code

The detail balance every founder worries about

Founders often fear that patents force them to “give everything away.” That is not true.

You must explain the invention well enough that a skilled person could understand and reproduce it. You do not need to include every parameter, dataset, or line of code.

The goal is to teach the idea, not to open-source your system.

What “enough detail” looks like in practice

Describe the structure, the flow, and the key choices. Explain why steps happen in a certain order. Show how inputs turn into outputs.

If there are ranges or options, you can describe them as examples, not fixed values.

This gives you protection without locking you into one narrow version.

Why vague patents fail

Some founders try to stay so high-level that the patent becomes hollow. Examiners will reject this as unclear or unsupported.

Clear explanation is your friend. It does not weaken you. It strengthens the fence.

How Tran.vc helps founders feel safe here

Tran.vc guides founders through this balance. You get help deciding what to disclose and how to phrase it so you protect the core without oversharing.

This is hard to do alone, especially the first time. You can apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Step seven: watch what you share before you file

Why timing matters more than most founders think

Public disclosure can kill patent rights in many countries. That includes talks, posts, demos, and sometimes even customer pilots.

Founders often build in public, which is great for learning, but risky for patents if done too early.

The safe mental model

If you would not want a competitor to read it and copy your approach, do not publish it before you talk to a patent expert.

This does not mean you must be silent. It means you should be intentional.

Common accidental disclosures

Demo videos that show internal logic, blog posts that explain architecture, and sales decks that reveal the “secret sauce” can all count.

Even friendly conversations can create risk if recorded or shared.

How to move fast without freezing

The solution is not fear. The solution is early strategy.

If you identify patentable ideas early, you can file provisional applications and then share more freely.

Where Tran.vc creates leverage

Tran.vc helps founders move early, before accidental disclosure, without slowing product momentum.

By handling IP strategy in parallel with building, you stay fast and protected. Apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

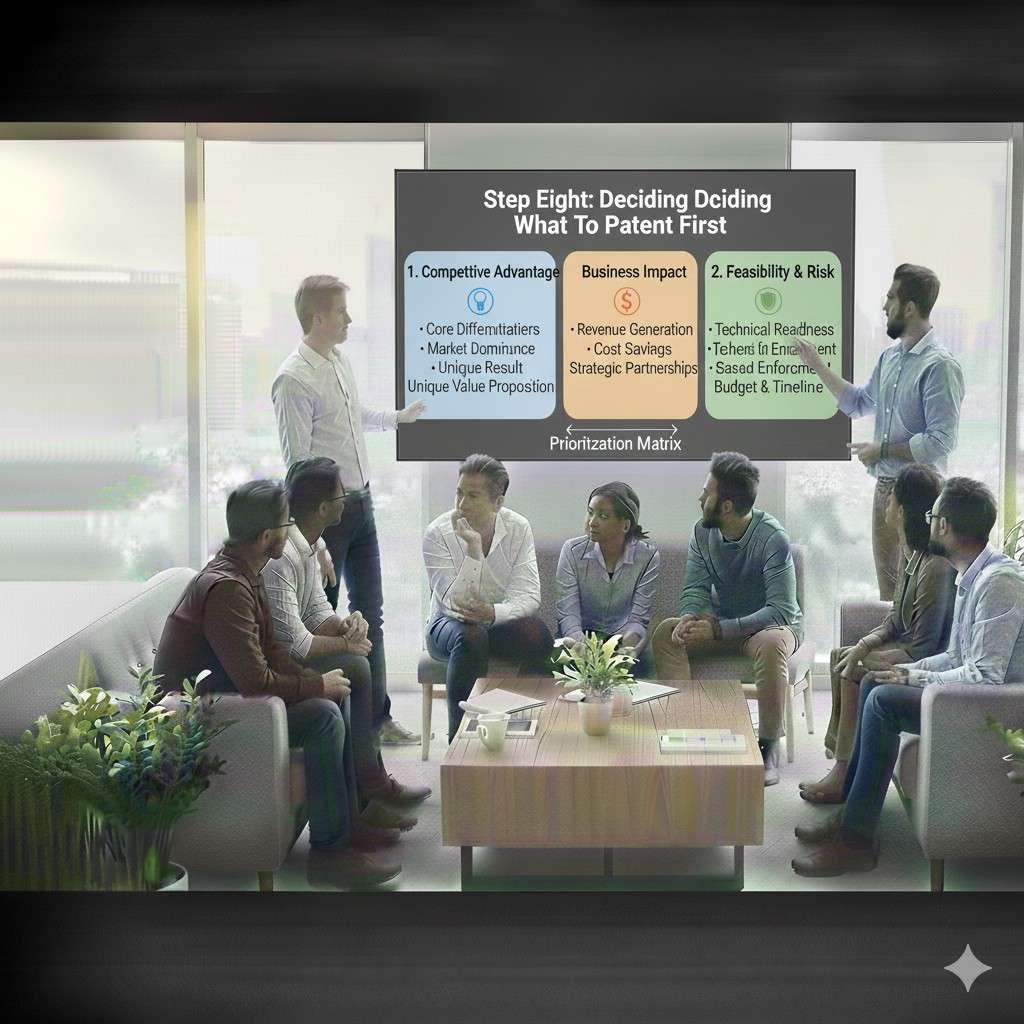

Step eight: deciding what to patent first

You do not need to patent everything

Trying to patent every idea is expensive and unnecessary.

The goal is to protect the core advantage that would hurt the most if a competitor copied it.

A useful prioritization question

Ask: “If someone copied this one thing, would my company lose its edge?”

If the answer is yes, that is a strong candidate for early filing.

Think in layers, not single shots

Many strong companies build patent families over time. The first filing covers the core. Later filings cover improvements and variations.

This layered approach builds a moat without draining early resources.

How Tran.vc supports long-term thinking

Tran.vc does not just file a patent and disappear. The focus is on building an IP roadmap that grows with the company.

That roadmap helps with fundraising, partnerships, and long-term defense. You can apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

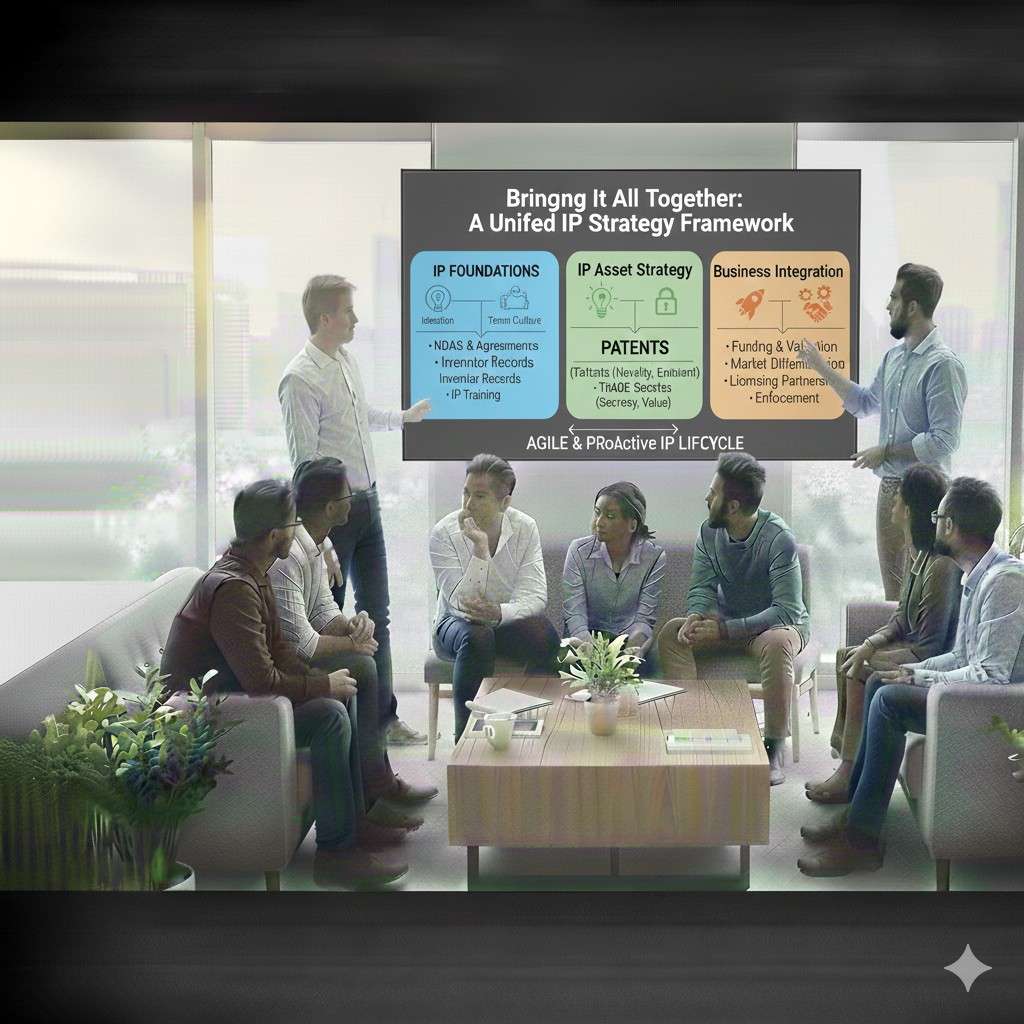

Bringing it all together

A simple final self-check

If your deep tech idea is a specific method or system, solves a real technical problem, is new in how it works, is not an obvious step, and can be clearly explained, there is a strong chance it is patentable.

You do not need perfection. You need clarity and timing.

Why early IP changes everything

Strong IP gives you leverage. It helps investors take you seriously. It makes competitors think twice. It lets you raise on your terms, not from fear.

This is not about paperwork. It is about control.

Your next move

If you are building in AI, robotics, or deep tech and want to know where your real patent opportunities are, the fastest way is to talk to people who have done this before.

Tran.vc exists to do exactly that, with up to $50,000 of in-kind patent and IP support for technical founders.

You can apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/