Most founders think patents are only for “the model” or “the robot.” The shiny thing. The demo thing.

But in real AI and robotics companies, the real advantage often lives somewhere else. It lives in the work you do every day that nobody sees. The boring parts. The parts that feel like “just engineering.”

Your training pipeline. Your data workflow. Your labeling steps. Your evaluation loop. Your safety checks. Your way of catching bad data before it breaks a model. Your way of making a model learn faster with less data. Your way of moving from raw sensor logs to clean training sets without losing key signals.

That’s where teams quietly build a moat.

And yes—many of those pieces can be patented.

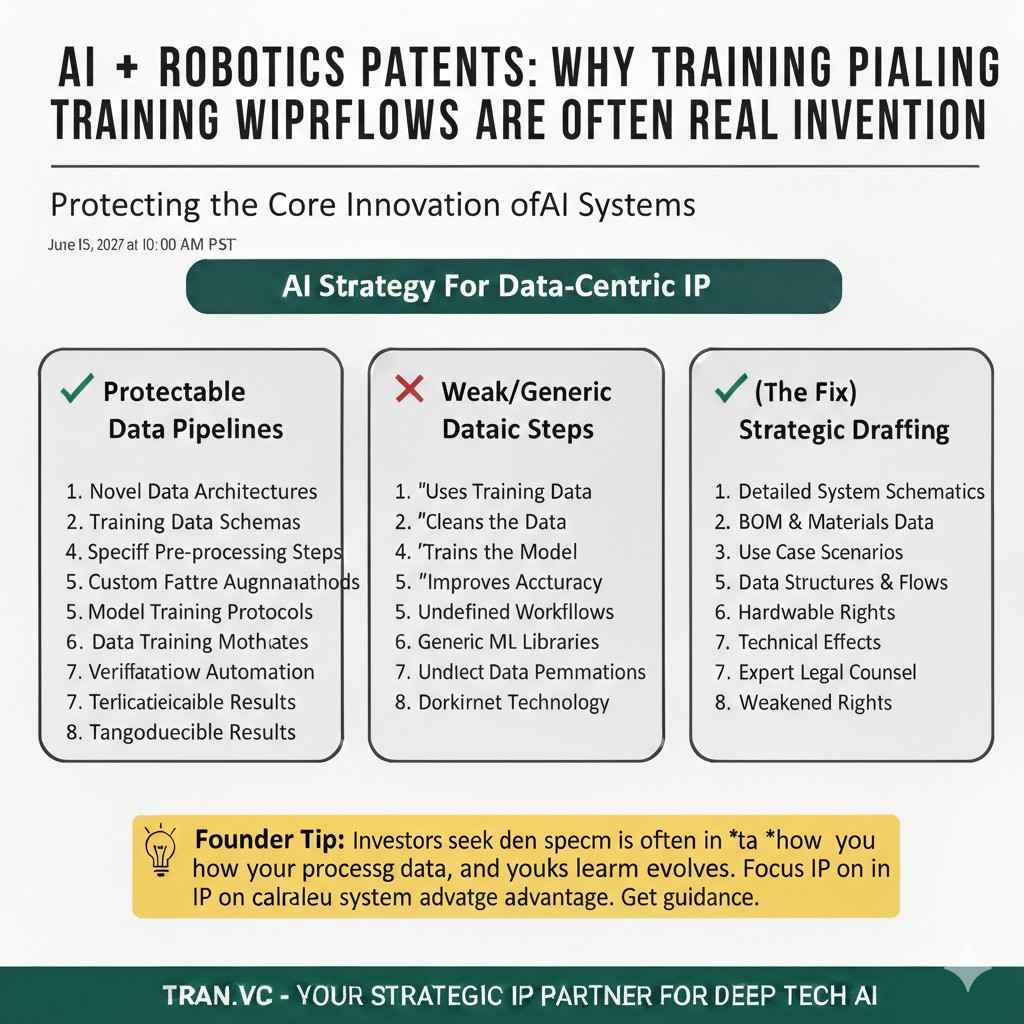

Not everything, of course. You can’t patent “we train a model on data” or “we use Python scripts” or “we have an ETL pipeline.” But you can patent specific, concrete methods that solve real technical problems in how training data is built, verified, transformed, fed, and used. Especially when you can show clear steps, clear inputs, and clear outputs. Especially when your workflow produces a measurable result: fewer labeling hours, better accuracy, lower compute, less drift, stronger safety, faster retraining, more reliable deployment.

This article is about what’s possible—without hype, without legal fog, and without turning your engineering team into paperwork writers.

At Tran.vc, this is exactly the kind of work we help technical founders protect early. We invest up to $50,000 worth of in-kind patent and IP services so you can lock in your advantage before you raise a big round. If you’re building in AI, robotics, or deep tech, you can apply anytime here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Now let’s get practical.

Why training pipelines and data workflows are often the real invention

When investors talk about defensibility, they usually look for one of three things:

- data that others can’t get

- a system that improves faster than others

- a product that is hard to copy even if someone sees the code

Your training pipeline and data workflow touch all three.

Here’s the truth: many models are replaceable. Many architectures can be copied. Many “features” can be cloned within months.

But if your team has built a reliable machine that turns messy real-world data into strong models again and again, that machine is the asset. It’s not a single training run. It’s the repeatable process.

In robotics, that is even more obvious. You are not training on clean text. You are training on noisy sensor feeds, camera frames, IMU streams, depth maps, lidar sweeps, force data, joint angles, gripper states, and logs from the real world. The data is big, messy, and full of edge cases. The pipeline you build to handle that mess is the difference between “cool demo” and “real product.”

And in AI for business, the same thing happens. You don’t just train once. You deal with shifting data. New users. New patterns. New fraud tricks. New terms. New regulations. New drift. You need a workflow that keeps the system correct and safe.

That workflow can contain patentable ideas.

A simple way to think about what can be patented

If you want to know if something in your training pipeline might be patentable, ask this:

Are you solving a technical problem in a technical way, with clear steps?

“Technical problem” could mean:

- data is noisy and breaks training

- labels are expensive and slow

- drift is hard to detect early

- training takes too long or costs too much

- data has privacy limits

- evaluation is unreliable

- the system fails in edge cases

- you need to trace where each data item came from

- you must meet safety rules and prove it

- you need to sync data from many sources with time alignment

- you need to learn from real-world feedback without poisoning the model

“Technical way” could mean:

- a method that transforms data in a specific new way

- a method that selects data or generates labels in a specific new way

- a method that uses feedback signals in a specific controlled way

- a method that runs on-device first and then merges server-side

- a method that validates data through a specific test sequence

- a method that detects drift with specific triggers and actions

- a method that maintains a data lineage record tied to training outcomes

The key is that it can’t be just a business plan. It can’t be “we store data and train.” It has to be something that another engineer would read and say, “Oh, that’s a real technique. I see how it works.”

And you don’t need a “brand new science breakthrough” either. In patents, practical engineering solutions can be strong if they are specific and well written.

That’s why founders who treat “data plumbing” like an asset often win. They stop seeing the pipeline as a cost center and start treating it like product.

What “training pipeline” really includes

Most teams use the phrase “training pipeline” to mean “a script that trains our model.”

In patents, you want to zoom out.

A full training pipeline often includes:

- how raw data is captured

- how it is cleaned and normalized

- how it is split into training and test sets

- how labels are created and checked

- how data is filtered to remove bad samples

- how augmentation is done and when

- how data versions are tracked

- how model runs are linked to specific data sets

- how errors are found and sent back into the pipeline

- how retraining is triggered

- how deployment checks happen

- how post-deploy feedback is collected and used

In robotics, you can add:

- sensor sync and time alignment

- simulation-to-real mapping

- human-in-the-loop correction

- safety gating

- control policy constraints

- handling of rare failures and near-misses

- event-based sampling from logs (not just random frames)

Each one of these can hide “small inventions” that add up.

A single pipeline can produce multiple patents if you break it into real technical modules.

And that is exactly how you build an IP wall early without distracting the team.

If you want help turning your pipeline into a set of clean patent claims, Tran.vc was built for that. You can apply anytime here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

The big misunderstanding: “We can’t patent this because it’s just data”

A lot of founders say: “We can’t patent data workflows. It’s just moving data.”

That’s like saying: “We can’t patent robotics because it’s just moving motors.”

A data workflow is not “just moving data” when it changes how a system learns, adapts, or performs.

The patent system often cares about:

- a clear process

- a clear technical improvement

- a clear way it is implemented

- a clear result

So if your workflow includes a specific method to:

- pick the best training samples

- reduce label noise

- generate labels from weak signals

- detect bad data early

- prevent training on poisoned data

- reduce compute by skipping redundant samples

- track drift and trigger retraining safely

- align multi-sensor streams better than standard tools

- convert human correction into model updates efficiently

- enforce privacy while keeping performance strong

…you may have something.

Even better: in many AI businesses, the “model” is a moving target. Next year it may change. But the pipeline—the way you turn your unique data into learning—often stays and evolves. That means the patents you file on the workflow can stay relevant even as models change.

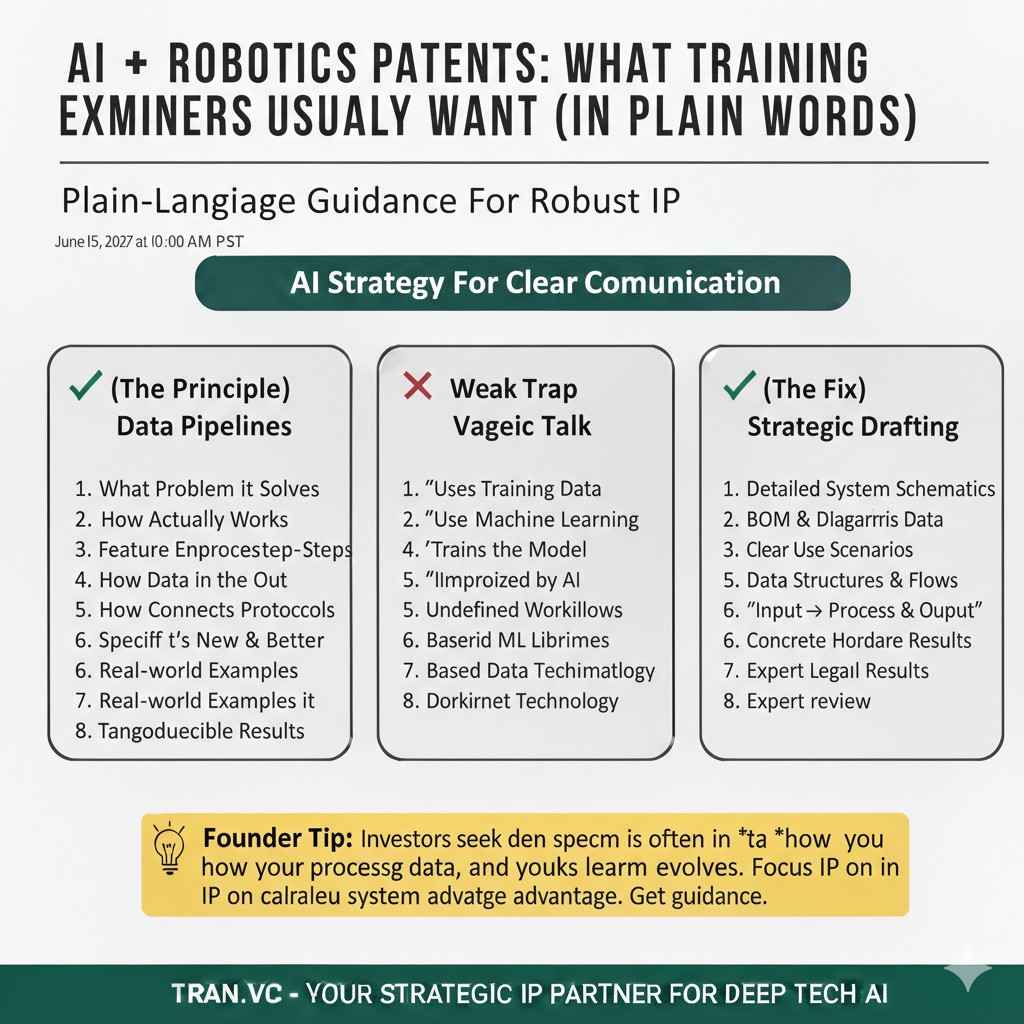

What patent examiners usually want to see (in plain words)

They want to see that you are not claiming something too broad.

If you write: “A system that trains a model using data,” that’s too broad and too old.

But if you write: “A method that detects mislabeled samples by comparing training gradients across two independent label sources, and then routes only high-disagreement samples to human review, and then updates a label confidence score used in the next training batch,” that’s a specific method.

Even if you don’t use that exact example, you can see the pattern:

- you define what inputs exist

- you define what steps happen

- you define what outputs are produced

- you define the technical benefit

- you define where it runs (edge, server, cloud, device, robot)

- you define how it plugs into training and deployment

This is why good patent work often starts with a simple founder interview where we map the real system.

Then we pull out the parts that are new and useful.

Your best raw material is already in your repo

If you feel like, “We don’t have time to invent patent stuff,” here’s the good news.

You already have it.

The best raw material is:

- your data validation scripts

- your labeling queue logic

- your active learning selection rules

- your augmentation strategy that is tied to failure cases

- your replay buffer setup

- your simulation randomization method

- your drift triggers

- your data versioning scheme

- your privacy filters

- your safety gating rules

- your evaluation harness and how it chooses scenarios

- your “hard example” miner

If any of those were built because standard tools failed, or because you hit a real wall, that’s a signal you may have something protectable.

A simple mental test:

If a strong competitor hired two good engineers and gave them six months, would they end up building something similar?

If the answer is yes, then you should consider patenting it now—before they do.

That is the whole point of early IP. Not because you love paperwork. Because you want leverage.

If you want to explore what parts of your pipeline might be patentable, Tran.vc does this every week with technical teams. You can apply anytime here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form

Where Patents Fit in the Training Pipeline

The pipeline is a system, not a script

A training pipeline is rarely just one training file that runs on a schedule. It is a system made of many small choices that work together. Those choices decide what data you trust, what data you ignore, and what data you send back for fixes. Over time, these choices shape the quality of your model more than any one architecture change.

When you look at it this way, the pipeline becomes a product. It is the machine that turns raw signals into learning. If your machine is better, you improve faster. If you improve faster, you win. That is why patents can sit naturally inside the pipeline, even when you are not trying to patent “AI” as a vague idea.

What a patent should protect in this context

In this context, a good patent does not try to own “training a model.” It protects a method that solves a real technical problem in the pipeline. The method has steps that can be repeated and tested. It produces a technical result that you can describe clearly, like reduced label noise or faster convergence or fewer unsafe outputs.

A strong patent also matches how your team actually works. It does not force you to change your system. It simply describes what you already do in a structured way, and then claims the parts that are truly your edge. Done well, it feels less like paperwork and more like turning your best engineering decisions into a business asset.

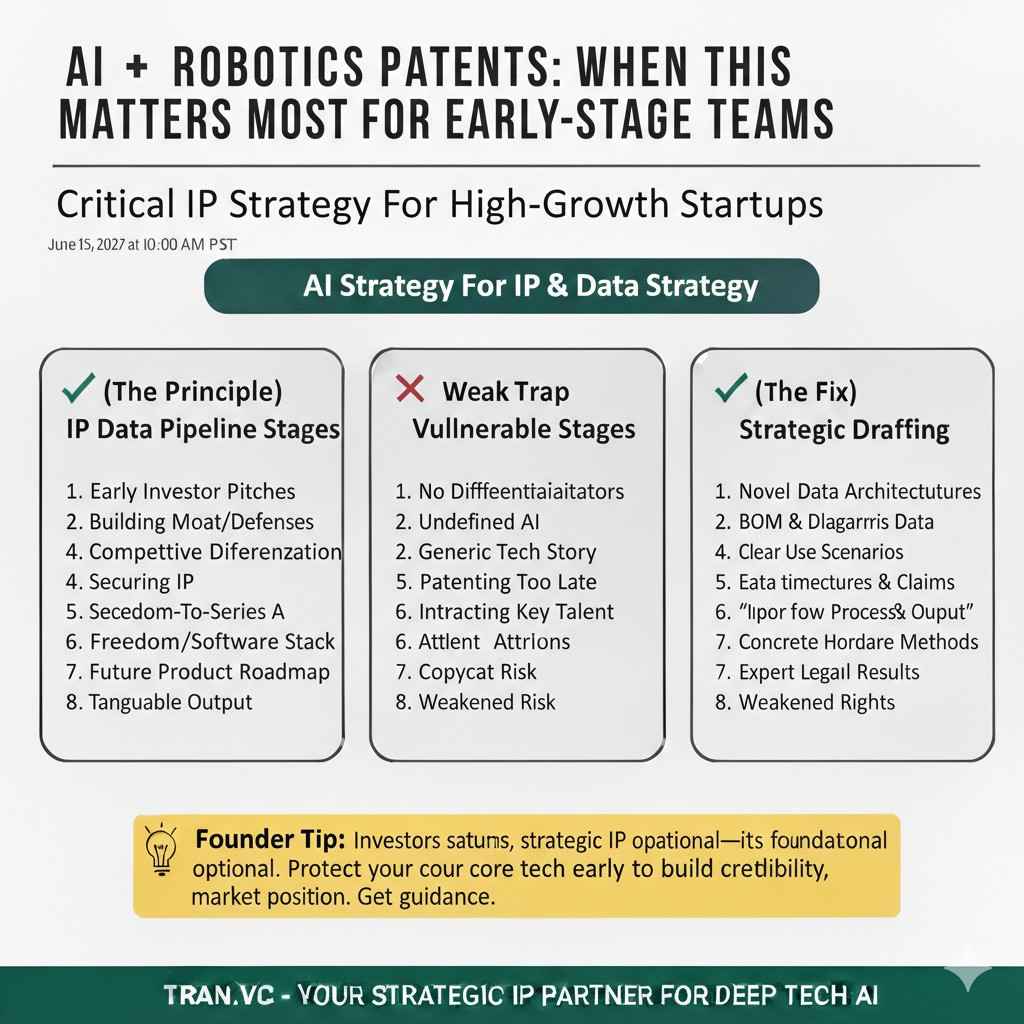

When this matters most for early-stage teams

Early-stage teams often ship fast and learn fast, but they do not pause to protect what they are building. This is understandable, because speed feels like survival. The problem is that speed without protection can become a trap, especially when a larger company can copy your process once it sees the shape of your product.

Training pipelines and data workflows are often built through painful iteration. You only arrive at the “right way” after many failed attempts. That painful learning is valuable. Patents are one of the few tools that let you lock in that learning while you are still small.

If you are building in AI, robotics, or deep tech, Tran.vc helps you do this early without slowing your build. We invest up to $50,000 worth of in-kind patent and IP services so you can protect what matters before you raise your seed. Apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

The Difference Between Data Workflows and Training Pipelines

Data workflow is about trust

A data workflow is the path your data takes from the world to your storage, then through cleaning, labeling, filtering, and versioning. It is the system that decides what is “good enough” to be used. It is also the system that decides what needs human attention. If your data workflow is weak, your training pipeline becomes fragile and unpredictable.

Patents in this area often focus on how you establish trust in data. That trust can come from consistency checks, cross-sensor alignment, anomaly detection, or rules tied to known failure modes. The key is that you are not simply storing data. You are validating it using a specific method that creates a reliable training set.

Training pipeline is about learning behavior

A training pipeline sits downstream from the data workflow, but it is not just “training code.” It includes batch construction, sample weighting, augmentation timing, evaluation logic, and retraining triggers. It is the part that decides how learning happens over time and how the system reacts when learning goes wrong.

Patents in this area often focus on the mechanics of learning. That might be a method that chooses what to train on next, or a method that identifies where the model is uncertain and routes those cases for labeling. The invention is often the loop, not the model.

Why separating them helps your IP strategy

When founders mix these two ideas, they tend to file weak patents that are too broad and too fuzzy. When you separate them, you can see clearer inventions. The data workflow can have its own patent claims. The training pipeline loop can have different claims. Even the “bridge” between them, like label confidence scores that affect sampling, can be its own protectable method.

This separation also helps you tell a clean story to investors. You can explain that your defensibility is not only a model, but a reliable learning machine. That story feels grounded because it maps to real system parts. It also makes it easier to draft patents that survive scrutiny because the steps are concrete.

What “Patentable” Looks Like in Practice

The test of specificity

A patentable pipeline idea is not a slogan. It is a procedure. If someone asks, “What exactly happens first, second, and third?” you can answer without hand-waving. You can point to inputs, steps, and outputs. You can show where this runs, how it connects to your training process, and how it changes the outcome.

Specificity does not mean you reveal secrets in public. It means you describe the method at the right level, so it is clear and enforceable. Most founders are surprised by how much can be protected without giving away the “full recipe.” A good patent draws a strong boundary, while still leaving room for your implementation details to remain internal.

The test of technical improvement

The patent office and future investors both care about improvement. Improvement can be accuracy, but it can also be reliability, safety, latency, compute cost, stability under drift, or reduced human labeling time. Many data workflow inventions improve something other than accuracy, and those are often easier to defend because they address a clear pain point.

If your workflow reduced label cost by half, that is an improvement. If it prevented training on corrupted logs and cut failure rates, that is an improvement. If it allowed retraining in hours instead of days, that is an improvement. In patents, you want to describe the improvement in a way that ties back to the method steps.

The test of repeatability

A patentable method should be repeatable. That does not mean it always produces the same model. It means the process is stable enough that someone could follow it and get the same kind of benefit. Repeatability is what turns “we got lucky” into “we built a system.”

This matters a lot in robotics, where small data issues can cause large behavior changes. If your workflow includes checks that ensure time alignment between sensors, or ensures that rare event logs are captured and tagged correctly, that repeatable process is a real technical contribution. It can often be described in patent claims without being vague.

High-Value Areas to Look For Inside Your Workflow

Data quality gates that are tied to model behavior

Many teams have basic data checks, like missing values or format validation. Those are usually not new. What becomes interesting is when data checks are tied to downstream model behavior. For example, you may reject samples that cause unstable gradients, or you may route certain sensor logs for review when they match patterns linked to known failure modes.

When you tie data validation to training outcomes, you create a feedback relationship. That relationship can be a technical invention if it is implemented in a clear way. It moves beyond “clean data” and becomes “data quality gates designed for learning stability.”

Labeling systems that reduce human time without losing accuracy

Labeling is where many AI companies bleed money and time. The common idea is “human-in-the-loop,” but the real invention is how you choose what humans should label, and what you can label automatically with confidence. Many teams quietly invent systems that score label reliability, detect disagreements, and prioritize the most valuable samples.

A patent in this area might focus on the selection method, the confidence scoring method, or the review routing method. The claim is not “we label data.” The claim is “we reduce labeling cost by using this specific loop that selects and verifies the right samples.”

Sample selection and batch building rules

A big hidden lever in training is what goes into each batch, and in what ratio. If you always train on whatever arrives, you waste compute on redundant samples. Many strong teams build ways to mine hard examples, diversify batches, or adjust sampling based on drift signals. These steps can be more valuable than model tweaks because they change what the model learns from.

If you have a system that detects underperforming regions of the data and then increases their sampling weight until metrics recover, that is a loop worth looking at. If you have a method that detects redundancy and skips near-duplicate samples to save compute, that can also be a strong technical story. These are workflow inventions, not “model inventions,” and they can be protected.

Versioning and lineage that connects data to outcomes

In regulated spaces and safety-critical robotics, data lineage is not a nice-to-have. You need to know what data led to what model, and what model caused what behavior. Many teams build tracking systems that go beyond standard dataset versioning. They link data sources, labeling decisions, training settings, and deployment outcomes in a way that allows fast rollback and root-cause analysis.

If your lineage system includes a unique way to attach risk scores, confidence tags, or safety approvals to data and to training runs, that can be patentable. The value is not the database itself. The value is the method of linking and using lineage to control retraining and deployment.

How to Turn a Workflow Into a Strong Patent Story

Start from the failure that forced you to invent

The cleanest way to find patentable material is to start with what broke. Most good workflow inventions are born from failure. Maybe your model learned the wrong thing because a sensor drifted. Maybe labeling errors caused unsafe outputs. Maybe your training costs exploded. Maybe your evaluation looked good but real-world behavior was bad.

When you frame the invention as a fix to a real technical failure, the story becomes easy to write. It also becomes easier to defend, because you can point to why standard tools were not enough. Your patent does not need to mention every tool you tried. It needs to show the problem clearly and then show how your method solves it.

Describe the loop, not only the step

A single step can be helpful, but loops are where defensibility grows. Many training pipelines include loops like “collect data, label it, train, evaluate, find failures, collect more of that kind of data.” The invention often sits in how you close that loop. It might be how failures are detected, how data is chosen in response, or how labeling is scheduled.

When you describe the loop, you show that your system improves over time in a controlled way. That is valuable because it creates a repeatable learning machine. In patents, loops also create multiple claim angles, because you can claim the detection step, the selection step, the routing step, and the retraining trigger step.

Keep it concrete without being narrow

Founders often worry that patents will be too narrow if they are specific. The goal is not to write a patent that only covers one exact line of code. The goal is to describe the method in a way that captures your core idea, while allowing variations. A good patent often describes a general structure, and then gives a few implementation examples.

This is one reason working with experienced patent counsel matters. It is easy to accidentally write something too broad and get rejected, or too narrow and get ignored. The sweet spot is protectable scope that matches how competitors would copy you.

If you want help finding that sweet spot, Tran.vc is built for this exact problem. We invest up to $50,000 in in-kind patent and IP services for AI, robotics, and deep tech startups. Apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/