Sanctions can kill a deal fast.

Not in a dramatic way. More like a quiet “we can’t proceed” from a bank, a law firm, a payment provider, or an investor’s compliance team. And when that happens, it does not matter how strong your tech is, how fast you are growing, or how excited the other side felt last week.

For deep tech founders—especially in AI, robotics, chips, and any product that can be used in more than one way—sanctions risk shows up earlier than you think. You may be building a clean, helpful product. But if your customer, supplier, contractor, data flow, or even a co-founder’s past location touches a restricted country or a sanctioned party, the deal can freeze.

This article is about avoiding that freeze.

It is not meant to scare you. It is meant to help you build with your eyes open, so you do not spend six months building momentum and then lose it in a single compliance email. We will talk about what sanctions are in plain language, where founders get trapped, and how to set up your company so you can pass diligence without panic.

And since Tran.vc works with technical founders on building IP and strong foundations early, we will also cover a part many teams miss: how sanctions and restricted-country issues can affect patent work, inventorship, filing strategy, and even who can legally support your R&D.

If you want to build a company that can raise clean, sell clean, and scale clean, you need to treat sanctions risk like a basic hygiene item—like security, taxes, and cap table.

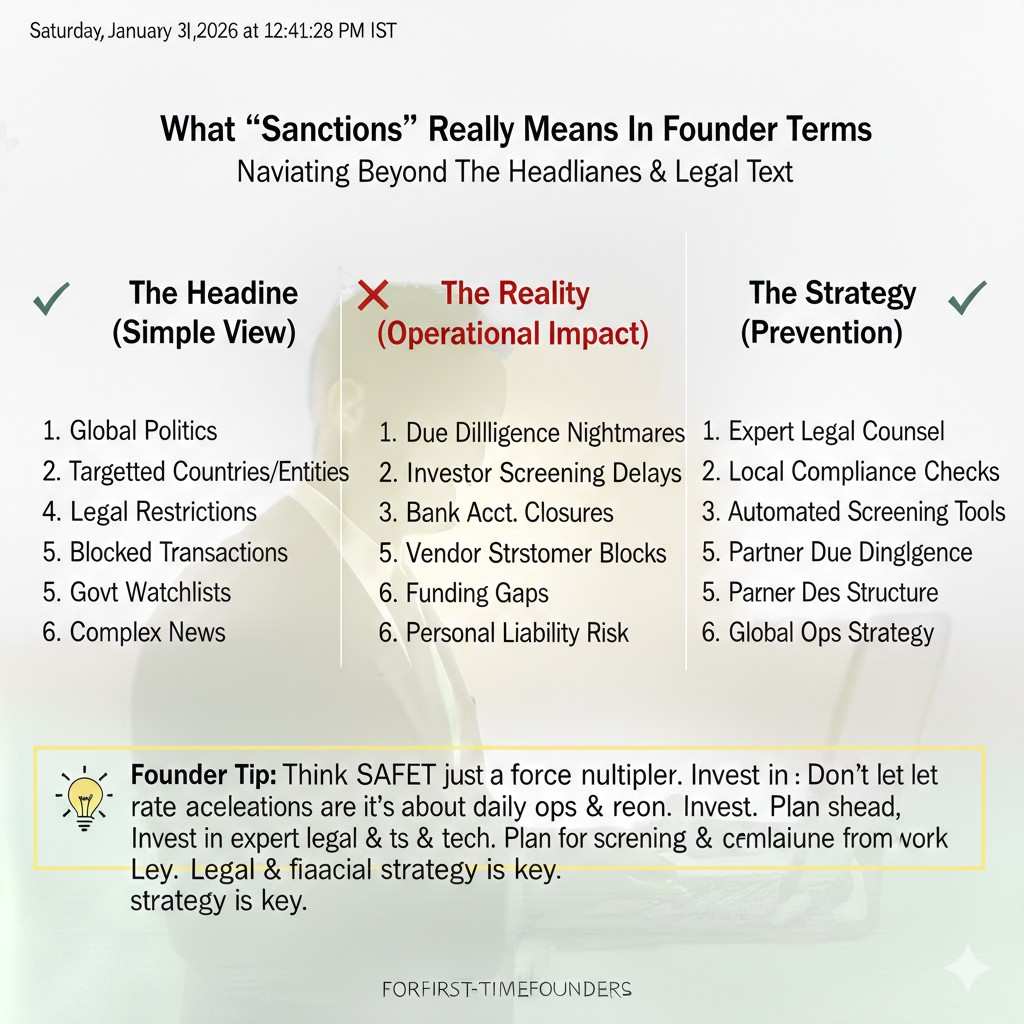

What “sanctions” really means in founder terms

Most founders hear “sanctions” and think it only applies to big defense firms or oil companies. That is a common mistake.

Sanctions are rules governments use to limit trade, money movement, services, and tech transfer with certain countries, groups, and people. In practice, sanctions do not only block shipping containers. They also block:

Money being paid to the wrong place

A company providing services to the wrong person

A startup selling software subscriptions in the wrong region

A founder sharing technical files with the wrong party

An investor owning part of a company that has the wrong ties

Sanctions can be broad (covering a whole country) or targeted (covering specific people, banks, ports, shipping firms, ministries, or companies). Some countries also have strict export control rules tied to “dual-use” tech, which is a fancy way of saying: “This can be used for civilian use, but also for military use.”

Many AI and robotics products can be viewed as dual-use, even if you never intended it. Computer vision that can detect objects. Autonomous navigation. Drones. Sensors. Edge computing. Secure comms. Model training pipelines. High-end chips. Even certain optimization systems.

Now layer that on top of how startups operate today: remote teams, global contractors, online payments, cloud services, open-source libraries, cross-border data. The number of ways to accidentally touch a restricted party is not small.

And unlike some other business risks, the “oops” factor does not protect you. Good intent does not fix a breach. What matters is what happened, who was involved, and whether you had controls in place.

Why this becomes a deal killer during fundraising

Investors do not like surprises. They like risk they can price.

Sanctions risk is hard to price. That is why many funds treat it like a red flag, not just a normal risk item.

Here is what happens inside many firms:

A partner likes you. They push the deal forward.

The firm asks for basic diligence docs.

Then the legal and compliance process starts.

Someone runs checks on your customers, vendors, and team.

They ask about countries you sell to, hire from, store data in, or pay into.

If anything looks unclear, they pause.

That pause is deadly in early-stage fundraising.

Because the pause is not just time. It is doubt. It is a signal that something is messy. And when a lead investor slows down, the rest of the round tends to wobble.

Even if you are clean, a weak answer like “we’re not sure” can cause delays. And delays are expensive. They distract founders, burn runway, and can force you to accept worse terms later.

A lot of founders think they will “handle it later” when they are bigger. But the truth is the opposite: the earlier you set clear rules, the easier it is. Early is when you still have the power to say “no” to risky deals and to shape how your company works.

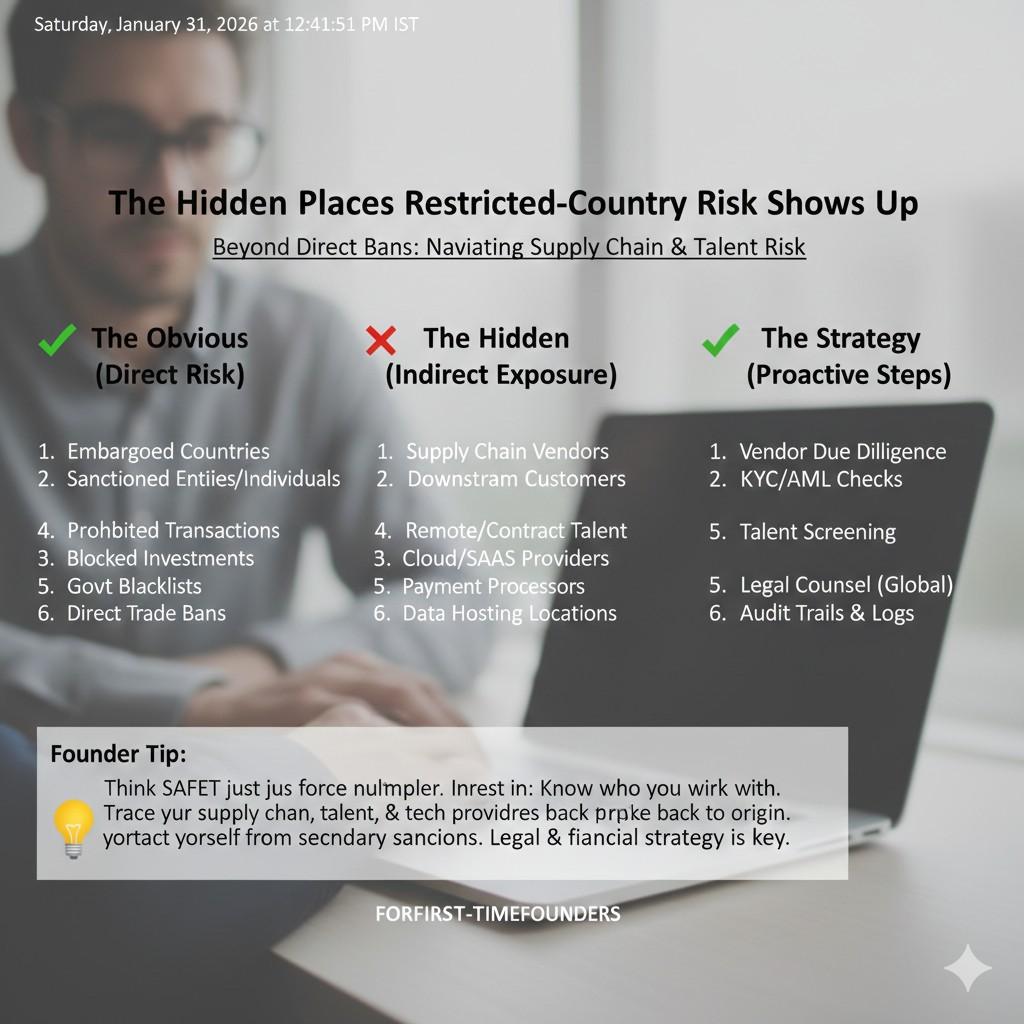

The hidden places restricted-country risk shows up

Most teams only check “where are our customers.” That is not enough.

Sanctions and restricted-country exposure often comes from places you do not expect.

Your first revenue customer

Early revenue is exciting. A paid pilot can feel like proof the market is real. But a single risky customer can poison diligence.

It is not just “the country” where the customer is based. It can be:

A customer headquartered in a normal country but owned by a sanctioned group

A reseller that sells into restricted regions

A “consulting partner” that brings you work but does not disclose the end user

A payment routed through a bank that is on a restricted list

If an investor’s compliance tool flags a name, they will ask you to explain it. If you cannot explain it clearly, the deal can stall.

Your contractors and hires

Remote hiring is normal. Many great engineers live all over the world. But you must understand what “restricted” means in your context.

Sometimes the issue is not the person. It is where the work happens from. Or how you pay them. Or what the work involves.

For example, if your tech is sensitive (AI, robotics, encryption, mapping, drones, chips), some services may be treated as “exporting” technical help. “Export” does not only mean shipping hardware. It can mean sharing certain technical details across borders.

A founder can also create risk by casually sharing internal repos, model weights, design files, or training data with someone in a restricted location.

Your supply chain and lab work

Robotics startups buy parts from many sources. Sensors, motors, boards, GPUs, test rigs. You might not know who the distributor is tied to. Or where the parts really originate.

A small “we can get you these parts fast” deal can later show up as a diligence question: “Why are you buying from this supplier?” If the supplier is linked to a restricted party, you now have a problem.

Your cloud and data

If your product is software, you might assume sanctions do not apply. But cloud services, data storage, and user access can create exposure.

If you allow signups from everywhere, you may accidentally provide service to restricted areas. If you do not have basic country blocks or screening, that can be viewed as weak controls.

Some teams also let overseas contractors access production data without thinking through the rules. That is a common mistake.

Your cap table and “who owns what”

Even if your company itself is in the U.S., investors will ask: who owns it?

If a shareholder, advisor, or early backer is a sanctioned person or is tied to a restricted regime, your cap table can become a problem. The same goes for complex ownership chains through holding companies.

This shows up often with friends-and-family checks or early angels. The money feels harmless at the time. But later, when a larger investor needs clean diligence, it becomes a blocker.

The extra layer for AI, robotics, and deep tech founders: tech transfer risk

In many industries, the product is easy to describe. In deep tech, the product is knowledge.

That creates a special challenge: you can trigger export or sanctions rules by sharing technical details, not just by shipping goods.

Founders trip here when they:

Send detailed design docs to overseas partners

Share model training methods with a contractor abroad

Give a demo that includes sensitive features to the wrong audience

Collaborate on research with parties tied to restricted entities

Publish code that was developed under certain restricted arrangements

You do not need to be building weapons to face this issue. You just need to build something that could be used in defense or surveillance, or that relies on controlled compute or sensors.

This is why many investors are more cautious with AI and robotics companies. Not because they dislike the space. Because the compliance surface area is bigger.

If you prepare early, you can still move fast. You just move fast with guardrails.

How sanctions issues can affect patents and IP work

This is where many founders are surprised.

Patents are not just “paperwork.” Patent work involves sharing technical details with attorneys, filing systems, and sometimes foreign offices. It also involves inventors, assignments, and disclosures. If any part of that chain touches restricted countries or sanctioned parties, you can run into delays or limits.

Examples that can create problems:

An inventor is located in a restricted jurisdiction and needs to sign documents

A contractor abroad is treated like a co-inventor, creating cross-border issues

Your patent strategy includes filing in certain countries that have special restrictions

You are using a foreign-based service provider that triggers compliance checks

Your invention relates to dual-use tech and needs careful handling

This does not mean “do not file patents.” It means you want a clean, well-planned IP path so your filings are smooth, your inventorship is correct, and your investors see you take compliance seriously.

This is part of why Tran.vc invests in IP services early. Strong IP is not only about protection. It is also about being “clean” in diligence. If your IP chain is messy, it becomes a question mark. If it is clear and well documented, it becomes a strength.

If you want to build that kind of foundation, you can apply any time at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

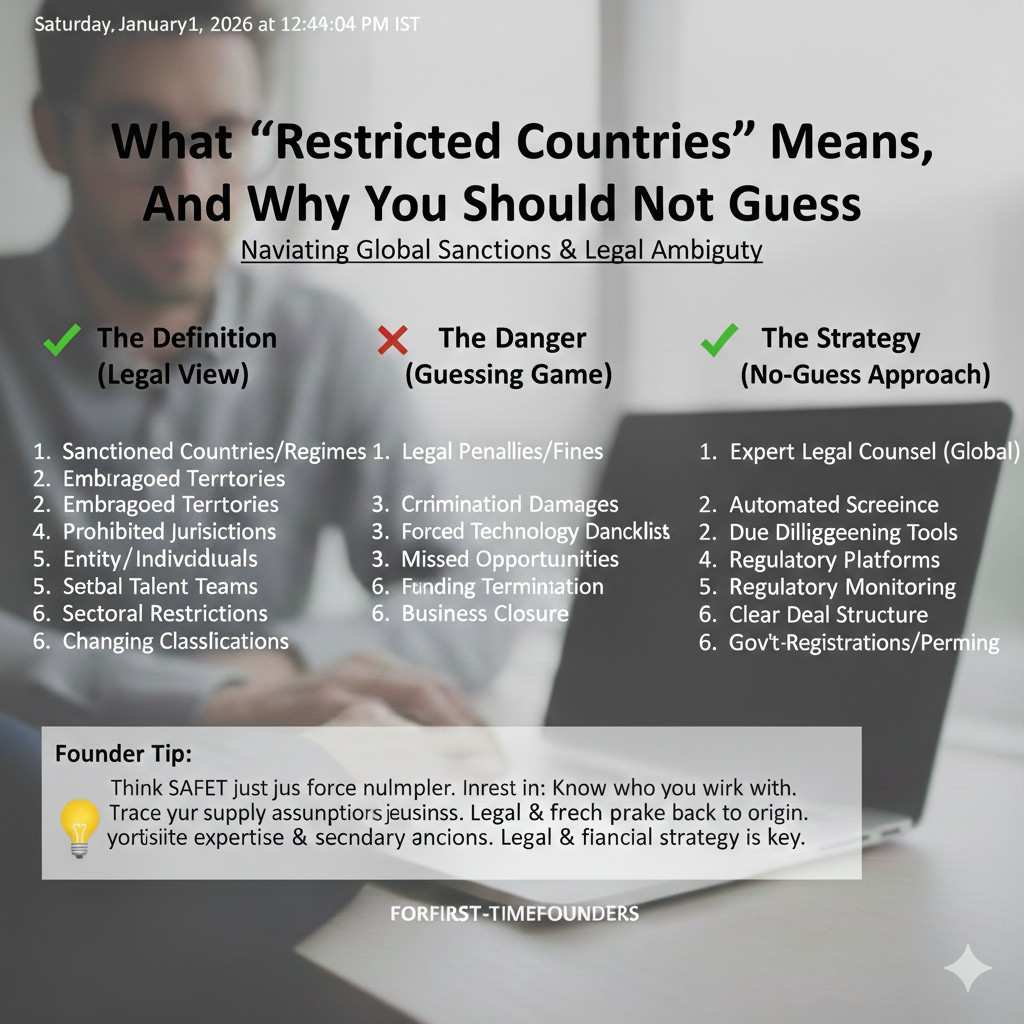

What “restricted countries” means, and why you should not guess

Founders often ask, “Which countries are restricted?”

The safe answer is: it depends on which rules apply to you.

If you are a U.S. company, U.S. rules matter a lot, even if you operate globally. If you use U.S. cloud services, U.S. payment rails, U.S. investors, or U.S. incorporated entities, you will likely face U.S. sanctions expectations.

Other countries and blocs also have sanctions regimes. So if you operate in the EU or UK, those rules can matter too.

The key point is not memorizing a list from a random blog post. Lists change. Rules change. And your company’s exact risk depends on your product, your team, your customer set, and your geography.

Instead of guessing, you want to build a repeatable process:

You screen customers and partners

You restrict service where needed

You document your decisions

You have a clear policy for the team

That way, when an investor asks, you do not say “we think we’re fine.” You say, “Here is our policy. Here is how we screen. Here is what we block. Here is the record.”

That is what turns a scary question into a quick checkbox.

The fastest way founders accidentally create exposure

It often starts with one of these moves:

You accept a pilot through a “friend of a friend” without asking who the end user is.

You use a reseller that refuses to disclose who they sell to.

You hire a contractor who logs in from a restricted area.

You let users sign up globally with no geo controls.

You take early money with no KYC and no ownership clarity.

None of these are evil choices. They are just common shortcuts. They feel like speed. But they can turn into the slowest, most painful kind of drag later—because they show up right when you are trying to close a round or sign a big enterprise contract.

A simple rule helps: if you cannot explain who is on the other side of the deal, you should not do the deal.

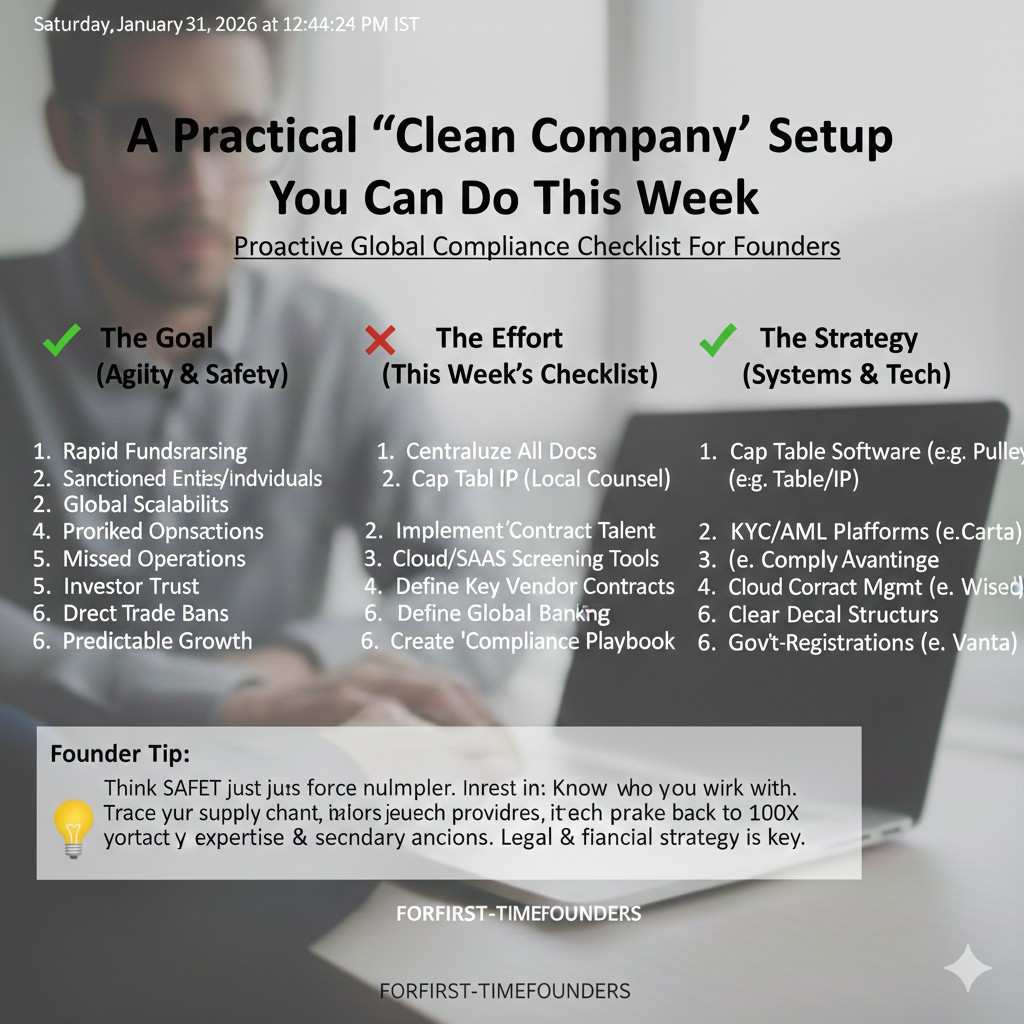

A practical “clean company” setup you can do this week

You do not need a huge compliance department. You need basic founder habits.

Start with your intake points:

When money comes in

When money goes out

When your product is accessed

When sensitive tech is shared

Then create small guardrails around those points.

For example:

Have one person on the team own “customer screening” as a role, even if it is just the CEO today.

Use standard onboarding questions for any paid deal, even small ones.

Keep a simple log of who the customer is, where they are, and who the end user is.

Write down which countries you do not serve, and implement geo blocks where needed.

Ask contractors where they will work from and make it part of the contract.

Keep your cap table clean with clear identities and signed documents.

None of this needs to be heavy. It just needs to be consistent.

If you do this early, you also send a signal: you are the kind of founder who can handle real enterprise sales, real audits, and real scale.

And that makes investors more comfortable.

The common deal-killers and how they show up in real life

The “small pilot” that triggers a full stop

A pilot can feel harmless because it is small money. But compliance teams do not measure risk by invoice size. They measure it by who is involved and what flows across borders.

If the pilot customer is tied to a restricted country, a sanctioned bank, or a blocked end user, the risk is the same as a million-dollar contract. When an investor finds out later, they will wonder what else you did not check.

The fix is simple: treat every paid pilot like it will be audited later. Ask who the end user is, where they operate, and how funds will move. Keep the answers written down, not just in your head.

The reseller problem

Resellers can create distance between you and the end user. That distance is exactly what makes diligence hard. If the reseller refuses to disclose where the product ends up, you cannot prove you stayed away from restricted use.

This is a common trap for AI and robotics teams because resellers offer speed. They promise distribution in markets you do not have time to learn. The short-term gain can turn into long-term doubt during fundraising.

If you use resellers, make disclosure part of the agreement. If they will not agree, walk away. A deal you cannot explain is a deal that can collapse a round.

The silent risk in “free trials” and self-serve signups

Many startups do not think of a free trial as a “service.” But sanctions rules often care about providing services, not just selling hardware. A free trial that allows use in a restricted region can still be a problem.

Self-serve signups also create a screening gap. You may never learn who is behind an email address. If a compliance tool later flags a user record, you will be stuck proving you did not knowingly serve a blocked party.

A practical move is to set country blocks where needed, add basic checks on signups, and log what you do. You do not need perfect coverage on day one. You need visible intent and consistent controls.

The “friend of a friend” introduction

Warm intros are a core part of early sales. But warm intros also reduce skepticism. A founder hears “trust me” and skips the boring questions.

This is how risky deals enter a company. The buyer seems friendly, the pilot moves fast, and no one asks about ownership, end use, or where they bank. Then it shows up later in diligence, when you can’t reconstruct what happened.

Create a habit: every new customer gets the same quick checklist, even if your best mentor introduced them. That is not distrust. It is professionalism.

Restricted countries and restricted parties are not the same thing

Country-based restrictions

Some rules focus on geography. If the country is on a restricted list, certain activity is blocked or heavily limited, even if the buyer is a normal company.

This matters for software access, cloud services, and technical support. A founder may think, “We never ship hardware there,” while forgetting that the product is still being used there through the internet.

Your job is to decide, in writing, which regions you do not serve and what controls you use to enforce that. The goal is not perfection. The goal is to remove ambiguity.

Person- and company-based restrictions

Other rules focus on specific people and entities. A company can be restricted even if it sits in a country you normally do business with.

This is where founders get surprised. They do business with a “normal-looking” firm, then learn later that the firm is owned by a sanctioned person, or it routes payments through a restricted bank.

This is why basic screening is needed even when the country seems safe. If you rely only on geography, you will miss entity risk.

Ownership and “control” can change the answer

A buyer’s ownership structure can turn a clean-looking relationship into a blocked one. If a restricted party owns or controls the customer, the transaction may become prohibited depending on the regime and thresholds.

Founders often do not ask about ownership because it feels awkward. But enterprise buyers expect these questions. They do it themselves with suppliers.

A simple approach is to ask for a short ownership statement for larger deals. For small deals, at least confirm the legal entity name, location, and payment path so you can screen properly.

The four places diligence teams look first

Money in

Investors and banks focus on revenue sources. They want to see where payments come from, which banks are involved, and whether any customer names trigger alerts.

If you cannot produce a clean customer list with clear legal names and countries, that alone can slow diligence. Even if everything is fine, messy records look like hidden risk.

Start now: keep your CRM and invoicing system aligned. Use legal entity names, not nicknames. Save contracts and written confirmations in one place.

Money out

Payments to contractors, vendors, and labs create exposure too. A single vendor in a restricted region can be enough to trigger questions about services provided and technical transfer.

The risk gets bigger when the vendor touches product code, model weights, chip designs, or core robotics control systems. It is not only a payment issue. It is also a knowledge-sharing issue.

A strong practice is to tag vendors by what they touch. If someone touches sensitive tech, treat them with higher scrutiny and keep stronger documentation.

Product access

If your software can be used from anywhere, diligence will ask what you do to prevent access from restricted regions. They may also ask how you handle suspicious signups and what logs you keep.

Many founders answer with vague statements like “we don’t market there.” That is not a control. A control is a system setting, a policy, and evidence that it is enforced.

Even simple geo-blocking and sign-up checks are meaningful. They show you understand the problem and built guardrails.

Technical sharing

Deep tech diligence often includes questions about who had access to core designs and models. This matters for export control risk and for IP ownership clarity.

If you shared sensitive technical details with unknown parties abroad, it can raise two concerns at once. First, compliance risk. Second, whether the IP chain is clean and protectable.

The best move is to tighten access now and keep a clean record of who has repository access, what they worked on, and where they are located.

The founder’s “minimum viable compliance” playbook

Write a one-page policy you can actually follow

You do not need a long legal document. You need a clear internal rule set. It should say which regions you avoid, how you screen customers, and who approves exceptions.

A policy only works if the team can follow it without guessing. Keep it plain. Keep it short. Make it a living document you update as you learn.

When an investor asks, you can share it and say, “This is our process.” That alone reduces friction.

Add screening into your sales flow

Screening should happen before you send a contract, not after you get paid. The earlier you do it, the less painful it is to walk away.

You can build screening into the same step where you confirm billing details. Collect legal entity name, country of incorporation, end-user location, and payment bank.

Then you keep a simple record. If you are ever asked later, you are not relying on memory.

Contract language that protects you

Many founders use lightweight agreements early. That is fine. But you still want a clause that says the customer will not use the product in restricted ways or transfer it to restricted parties.

This clause does two jobs. It discourages misuse and gives you an exit if you learn the buyer misled you. It also helps in diligence because it shows you did not ignore the issue.

If you do not know how to word it, borrow language from standard compliance clauses used in SaaS and enterprise agreements.

Control access to sensitive assets

Your most sensitive assets are often not your product UI. They are your repos, model weights, training data, chip designs, and control logic.

Limit access by role. Use separate environments for contractors when possible. Keep audit logs. Revoke access quickly when someone finishes.

These are security best practices, but they also support compliance. They help you show you prevented casual cross-border tech transfer.

Sanctions risk in IP work and patent strategy

Inventorship can create cross-border complexity

In patents, inventors matter. If a person abroad contributed to an invention, they may need to be listed as an inventor, and they may need to sign documents.

Founders sometimes try to “avoid” this by excluding people who helped. That is dangerous. Incorrect inventorship can weaken or even invalidate a patent later.

The right move is to structure work properly from the start. Be clear about who is doing inventive work, where they are, and how contributions are documented. That makes filings cleaner and reduces disputes later.

Using the wrong service provider can slow everything down

Patent work involves sharing technical disclosures. If your service providers or workflows trigger compliance flags, filings can slow or get complicated.

This does not mean you cannot work globally. It means you should choose reputable providers, keep clear records, and route sensitive work through teams that understand deep tech and cross-border issues.

Tran.vc’s model helps here because the goal is not just filing patents. It is building an IP foundation that stands up in diligence. If you want that support early, apply any time at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Filing strategy should match your risk profile

Some founders file everywhere without thinking. Others avoid filing in certain places due to fear. Both extremes can be costly.

A smart filing strategy considers where you will sell, where competitors will copy, and what markets matter for long-term value. It also considers compliance and export realities tied to your technology.

This is where experienced patent counsel matters. You want a strategy that protects the moat while avoiding unnecessary friction.