Most small AI teams do not fail because the model is “bad.” They fail because simple decisions get made in a messy way. Someone trains on the wrong data. Someone ships a feature without a clear test. A customer asks, “How do you know it’s safe?” and the team has no calm answer.

AI governance is just the way you stay in control. It is not a big-company thing. It is not a pile of forms. For a small team, governance should feel like a few clear roles and a few steady routines. Like brushing your teeth. Small effort, done often, and it keeps the big pain away.

In this article, I’ll show you how to set this up in a way that fits a small team. No fluff. No heavy words. Just the roles you need, the habits that keep you safe, and the weekly rhythm that makes shipping faster, not slower.

And if you are building AI, robotics, or deep tech and you want to protect what makes your product hard to copy, Tran.vc can help. We invest up to $50,000 in in-kind patent and IP services so you can build a real moat early—without giving up control too soon. You can apply anytime here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

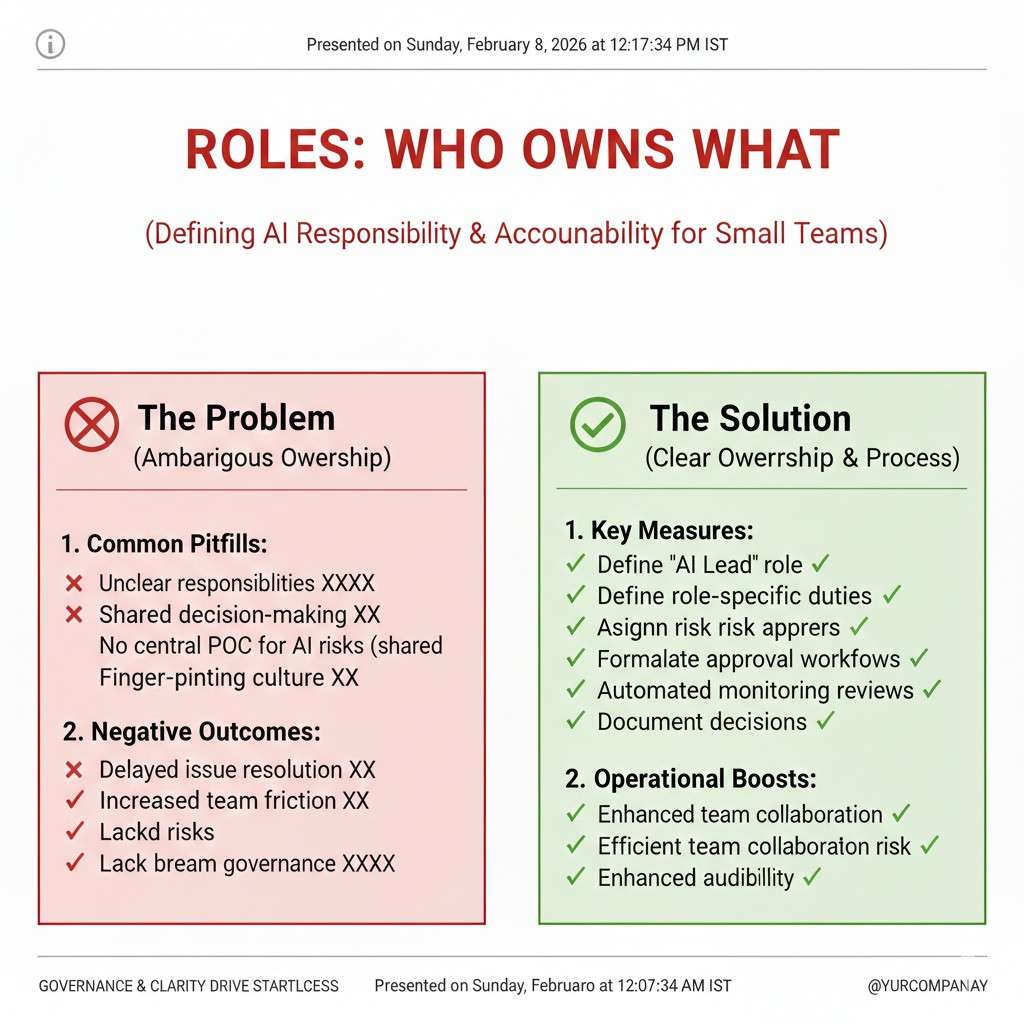

Roles: Who Owns What

Why roles matter more than policies

A small team cannot rely on long rules. Rules get skipped when people are tired or moving fast.

Roles are different. A role is a clear owner. When something goes wrong, you know who noticed it, who decided, and who fixed it. That is what keeps you calm when a customer asks hard questions.

Roles also prevent the “everyone thought someone else handled it” problem. That problem is common in AI work because data, code, and product decisions blur together.

If you only do one thing in governance, do this: name the owners.

The minimum set of roles for a small AI team

You do not need a big committee. You need a few hats that can be worn by the same people.

In most small teams, four roles are enough. Sometimes one person wears two hats. That is fine as long as the hat is named and the job is written down.

Think of these roles as lanes. They make decisions smoother, not slower.

In practice, the roles are: Product Owner, Model Owner, Data Owner, and Risk Owner. We will walk through each one in plain terms.

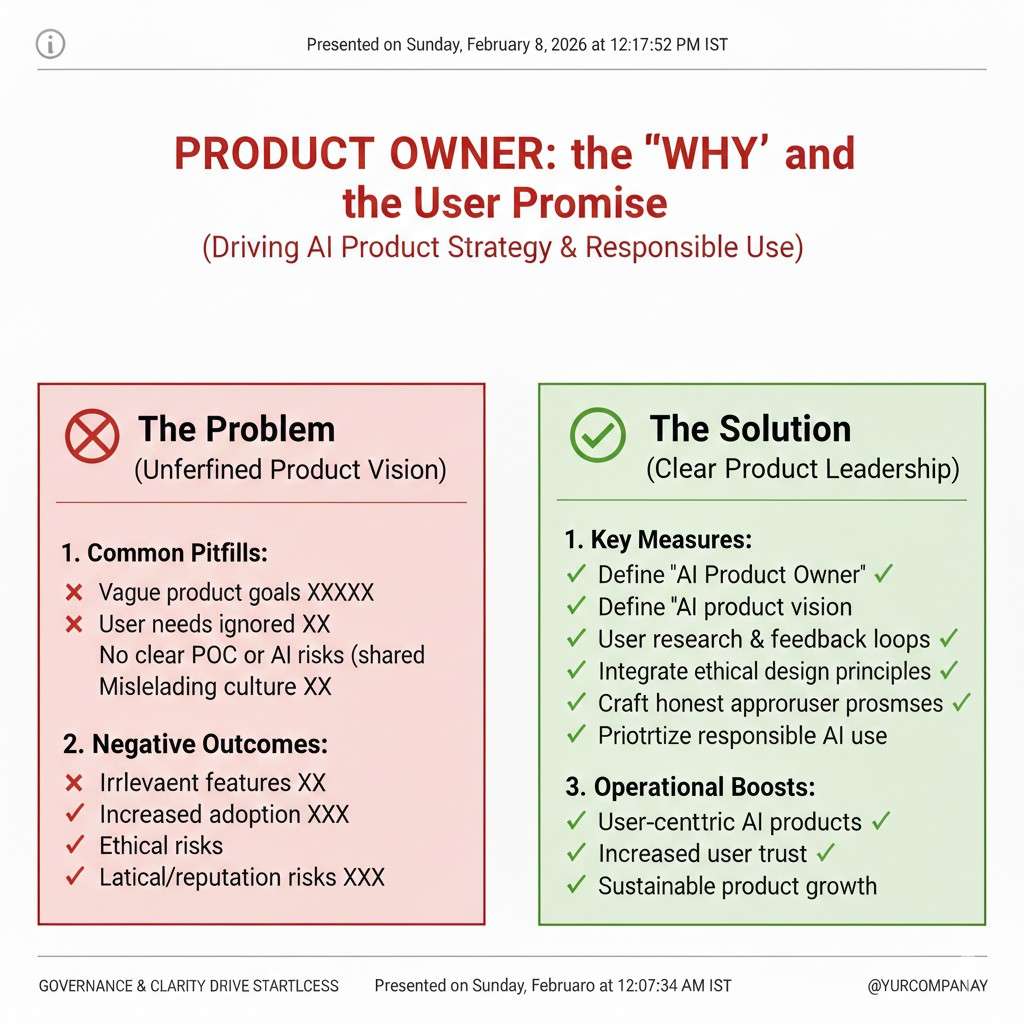

Product Owner: the “why” and the user promise

The Product Owner is responsible for what the AI feature is supposed to do for the user. This person owns the promise you make in your product and marketing.

They decide what “good” means in real use, not in a lab. They make sure the feature fits the workflow and does not surprise the user in a bad way.

When trade-offs happen, the Product Owner speaks for the user. They do not decide the math, but they decide the experience.

What the Product Owner does each week

They keep a short written note of what the system is allowed to do and not do. Not a long doc. A tight statement that a new hire could read in two minutes.

They review support tickets and user feedback with an “AI lens.” If users say, “It feels random,” or “It changed,” that is governance work.

They also approve what you show the user: labels, warnings, and any place you explain how results should be used.

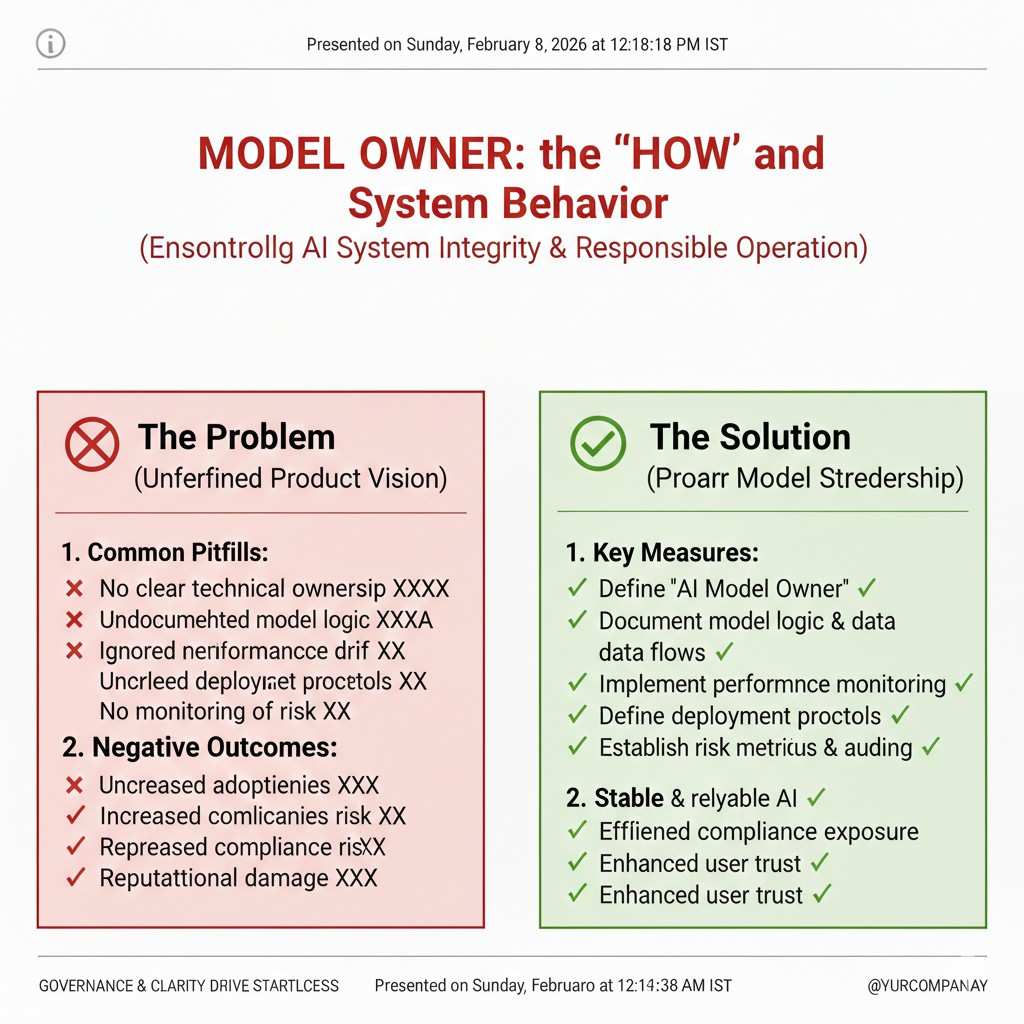

Model Owner: the “how” and the system behavior

The Model Owner is responsible for the model choices and how the system behaves. This can be a lead ML engineer, a founder, or a senior full-stack person who owns the model pipeline.

They own the key decisions: model type, tuning steps, and how the model is evaluated. They do not need to be perfect. They need to be consistent and able to explain decisions later.

When an issue comes up, this person can answer, “What changed?” without guessing.

What the Model Owner does each week

They keep a simple change log. Each time the model changes, they record what changed and why. It can be as small as a short entry in your repo.

They review model quality numbers and look for drift. Drift just means the system is slowly acting different than it used to.

They also define the “stop rules.” A stop rule means: if a metric drops under a certain point, the team pauses release and fixes the issue.

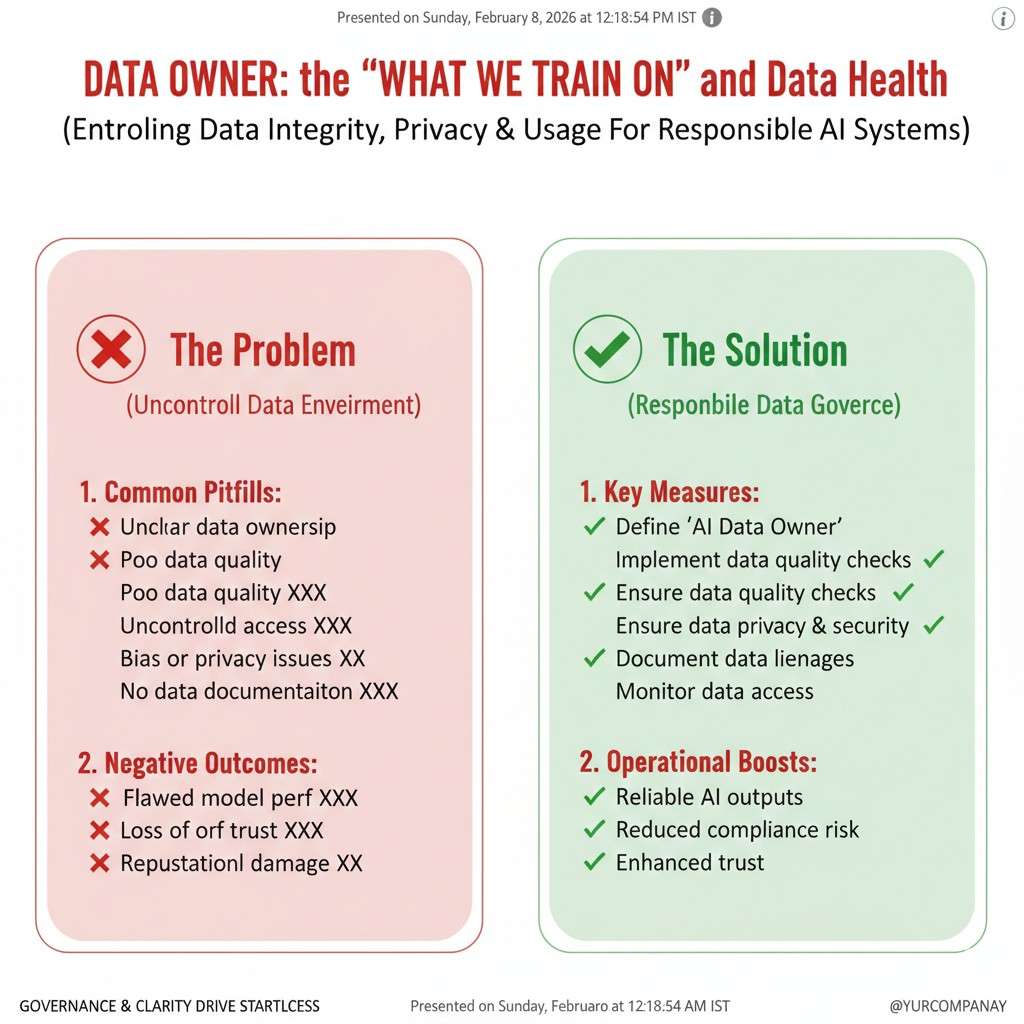

Data Owner: the “what we train on” and data health

The Data Owner is responsible for the training data and the data used in the product. This is one of the most important roles because bad data creates hidden risk.

They do not need to be a data scientist. They need to be the person who says, “Yes, we can use this,” or “No, we cannot.”

They make sure data is sourced in a clean way, stored safely, and handled with care.

What the Data Owner does each week

They track where data comes from and what rights you have to use it. This matters for trust, and it matters for IP. If your data is messy, your moat is weaker.

They run basic checks for missing values, odd spikes, and label noise. They also watch for personal data slipping into places it should not be.

They manage retention rules, which means how long you keep data and when you delete it.

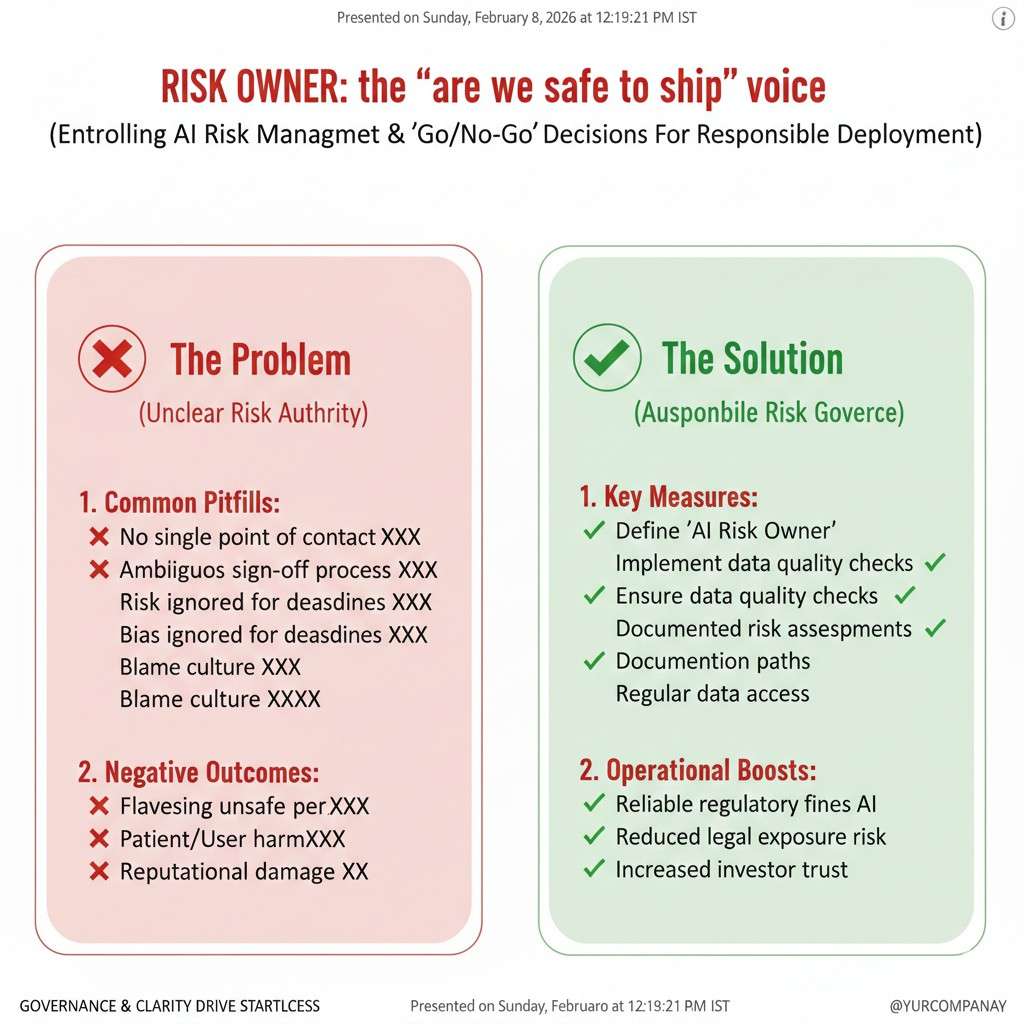

Risk Owner: the “are we safe to ship” voice

The Risk Owner is responsible for saying, “This is safe enough,” or “Not yet.” That does not mean they block everything. It means they keep the team honest about real-world harm.

In a small team, the Risk Owner is often the CEO, the CTO, or a product leader with a strong user focus. The key is that they are respected.

They help the team see risks early, when fixes are cheap.

What the Risk Owner does each week

They review the top risks and decide which ones must be handled now. They do not need a long list. They need the right list.

They approve the plan for testing and release. They also lead the review when something goes wrong, so the team learns and improves.

They make sure you can explain your system to a customer in plain words, without hiding behind jargon.

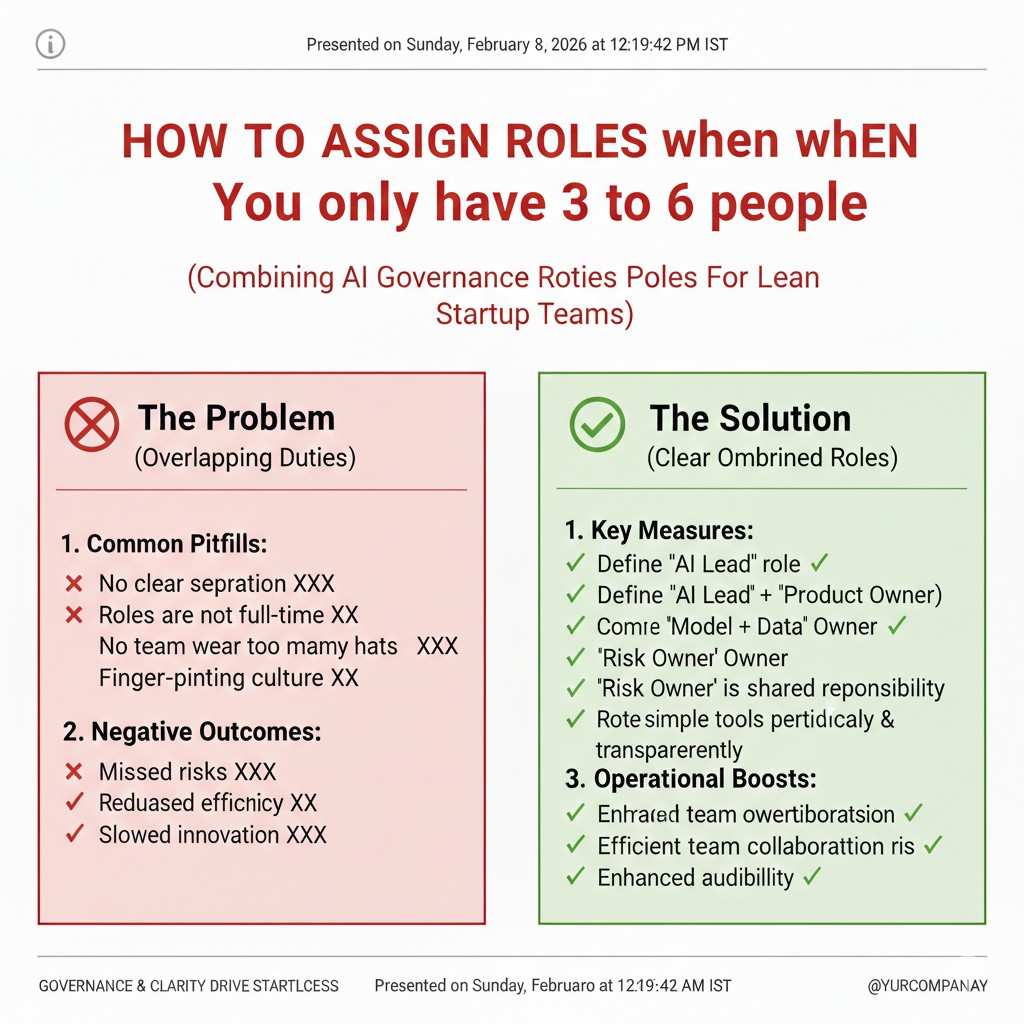

How to assign roles when you only have 3 to 6 people

Small teams often worry that roles will add meetings. The opposite happens when roles are clear. Decisions speed up because owners are known.

Start by writing the names next to the four roles. If one person holds two roles, write it down. That is still better than leaving it fuzzy.

Then write one paragraph under each role: what they own, what they review, and what they can decide alone.

How Tran.vc fits into this early

When you build AI, governance and IP connect. Many teams do not notice this until a large customer asks for proof, or an investor asks what is defensible.

Tran.vc helps technical teams set up smart IP strategy early, so your inventions become assets. That includes the invention story behind your models, your data pipelines, and the system choices that make your product unique.

If you want support building an IP-backed foundation while you build the product, you can apply anytime here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

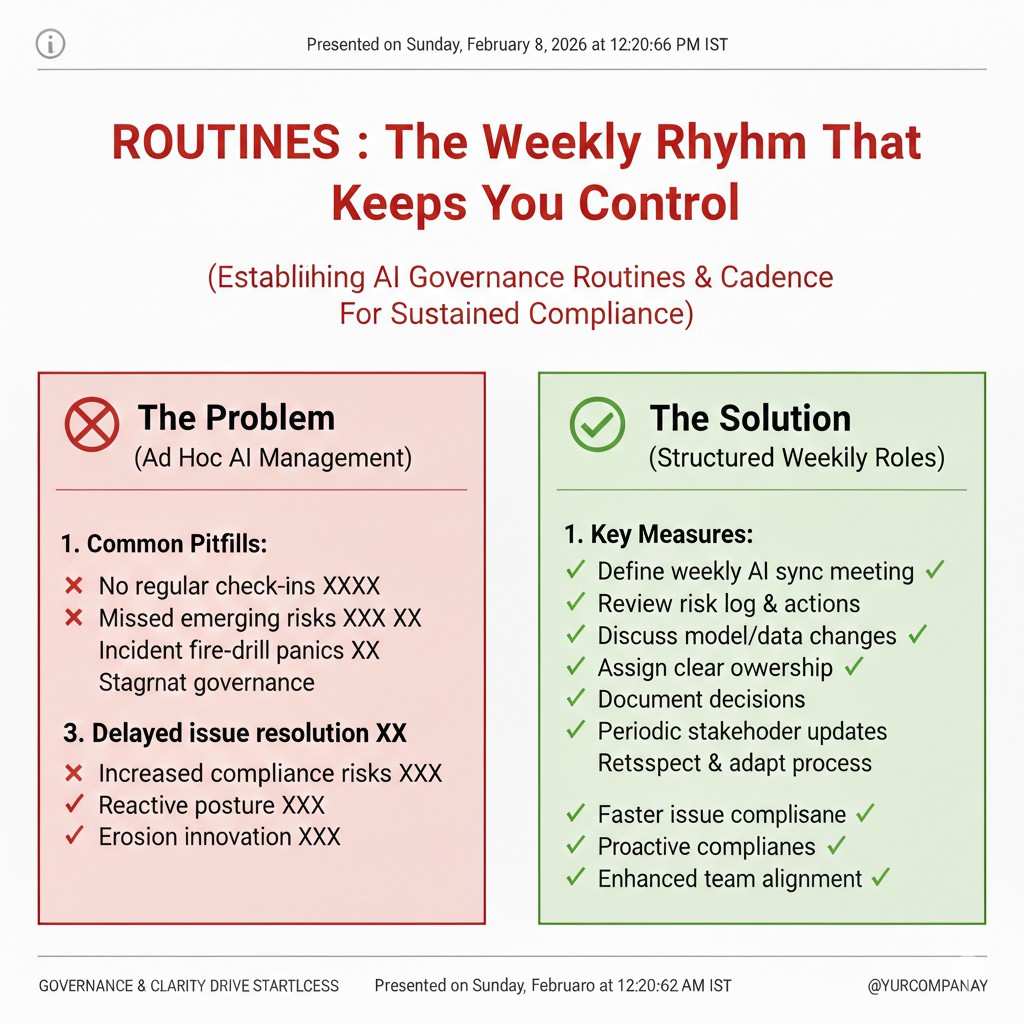

Routines: The Weekly Rhythm That Keeps You in Control

Governance should feel like a habit, not a project

The biggest mistake is treating governance like a big one-time effort. Teams write a doc, feel good, and then never look at it again.

For small teams, governance works best as a rhythm. Short, repeatable routines that happen even when things get busy.

These routines should fit inside work you already do, like standups, code review, and release planning.

The “AI kick-off” routine for every new feature

Before building, take 20 minutes to agree on what the AI feature is for. This is where many issues start, so this routine saves time later.

You define the user goal, the input, the output, and what a bad output looks like. You also decide what should happen when the model is unsure.

This is not paperwork. It is a short alignment that prevents rework.

The “definition of done” for AI work

For AI features, “done” cannot mean “it seems to work on my laptop.” It must include checks that match real use.

You set simple acceptance rules. For example, you might require that the model meets a target on a test set that matches your current customers.

You also require basic safety checks, like how it handles edge cases and whether it gives strange answers when prompts change.

The weekly model review meeting

This meeting can be 25 minutes. It is not a long event. It is a steady check-in where the Model Owner shows what changed and how quality looks.

The Product Owner joins so quality is tied to user value, not just numbers. The Risk Owner joins so problems are seen early.

You do not debate every detail. You confirm the system is stable or choose one clear fix to run next.

The weekly data health check

Data changes quietly. That is why it is dangerous. A new customer segment arrives. Inputs change. Labels drift.

A weekly check helps you spot this before it becomes a support problem. The Data Owner shows simple signals: volume changes, missing fields, and any new data sources.

If something looks off, you decide whether to pause a release or adjust tests.

The release gate: a short “go or no-go” moment

Before you ship an AI change, take 10 minutes for a release gate. The goal is not fear. The goal is calm control.

You review what changed, what was tested, and what the worst-case impact could be.

If you cannot answer those questions quickly, that is a sign your process needs a small fix.

The incident routine: what to do when the model misbehaves

Even with care, issues happen. The question is not “will something break?” The question is “how fast do we learn?”

When an incident happens, you write down the time, what users saw, and what changed recently. You do not blame people. You find causes.

Simple Documentation That Actually Helps

Why most AI docs fail small teams

Most documentation is written too late and read too little. It is often copied from large company templates that assume legal teams, review boards, and months of process.

Small teams move fast. When docs feel heavy, they get skipped. When they get skipped, knowledge lives only in people’s heads. That is risky for shipping, for trust, and for future funding.

Good AI documentation for a small team should do one thing well: help you explain your system clearly, even under pressure.

The mindset shift: write for future you

The best way to think about documentation is this: you are writing for a tired version of yourself six months from now.

That future you might be in a customer call, an investor meeting, or dealing with a bug at midnight. They need quick clarity, not theory.

Every doc should answer simple questions fast. What does this system do? Why was it built this way? What should we watch out for?

The AI system card: your single source of truth

An AI system card is a short description of how your AI works in the real world. It is not marketing. It is not a research paper.

This card explains the purpose of the system, the type of inputs it uses, and the kind of outputs it gives. It also states the limits in plain words.

When someone new joins the team, this card is what they read first. When a customer asks how your AI behaves, this card guides the answer.

How to write the system card without overthinking

Start with the user problem. Write why the AI exists and what task it helps with. Keep this grounded in actual use, not future dreams.

Then explain, at a high level, how the system makes decisions. You do not need math. You need clarity. For example, does it predict, rank, suggest, or generate?

End with limits. Say what the system should not be used for and where it might fail. This builds trust, not fear.

Why limits increase confidence, not doubt

Many founders worry that writing limits will scare users or investors. In reality, the opposite happens.

Clear limits show control. They show that you understand your system and are not hiding behind vague claims.

Investors and enterprise buyers look for this maturity early, especially in AI-heavy products.

The decision log: memory for your team

AI systems change often. Models get tuned. Data sources change. Thresholds move. Without a record, teams forget why choices were made.

A decision log is a running note of key choices and the reasons behind them. It does not capture everything. It captures what would be hard to remember later.

This log saves hours of debate and helps new team members ramp faster.

What belongs in a decision log

You write down decisions that affect behavior, risk, or quality. For example, choosing one model over another, or changing how confidence is handled.

Each entry answers three things: what changed, why it changed, and what you expected to happen.

When reality does not match expectation, this log becomes a learning tool, not a blame tool.

Keeping the decision log lightweight

The log should live where the work lives. For many teams, that is the repo or a shared doc linked to code changes.

Entries should be short. A few clear paragraphs are enough. If it feels heavy, it will not last.

The goal is continuity, not perfection.

The risk register: seeing problems before users do

A risk register sounds scary, but for a small team it can be very simple. It is a short list of the top ways your AI could cause harm or fail badly.

These risks can be technical, user-facing, or legal. What matters is that they are real, not hypothetical.

By naming them early, you gain control. Unnamed risks tend to grow quietly.

How to keep the risk register useful

You focus only on the top risks. Usually five or fewer is enough for an early-stage product.

For each risk, you note what could trigger it and how you would notice it. This makes risks observable, not abstract.

You review this list regularly and update it as the product changes.

Connecting documentation to daily work

Documentation should not live in a separate world. It should connect directly to shipping and support.

When a support issue appears, you check whether the system card or risk register needs an update. When a model change happens, you add to the decision log.

This loop keeps docs alive and relevant.

Documentation as leverage for IP and fundraising

Clear documentation does more than help your team. It strengthens your IP story. It shows what is unique about your system and how it evolved.

When patent attorneys look at your work, these docs help surface invention points that might otherwise be missed.

Tran.vc uses this kind of clarity to help founders turn real technical choices into defensible IP, early in the company’s life.

Why this matters before you raise

Many teams wait until a seed round to clean this up. By then, they are rushed and reactive.

Founders who start early raise with more leverage. They can explain their tech clearly and show that their moat is intentional.

If you want help building this foundation while staying lean, you can apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Making documentation part of your culture

Culture is not slogans. It is what you do when no one is watching.

When leaders refer to the system card, update the decision log, and talk openly about risk, the team follows.

This creates calm speed. You move fast, but with direction.