Functional safety in robotics sounds like a “later” problem.

Later, after the demo works.

Later, after the pilot.

Later, after you hire “the safety person.”

And that is exactly where many robotics teams go wrong.

Because functional safety is not a sticker you add to a robot at the end. It is a design habit. It is how you prove—on purpose—that your robot will not hurt people when something breaks, when sensors lie, when code crashes, when a motor sticks, or when a user does something you did not expect.

If you build robots, you already know this in your gut. A robot is not a simple app. It has mass. It has torque. It moves in the same space as humans. Even small robots can pinch fingers, trip people, strike faces, and crush hands. Bigger robots can do far worse. A single “rare bug” becomes a real injury when you have motion plus power.

So why do smart teams still fall into the same traps?

Because early-stage teams are under pressure to show progress. They optimize for speed, not proof. They ship a robot that works “most of the time,” and they tell themselves they will make it safe “before we scale.” Then a customer asks for a safety plan. An insurer asks for evidence. A partner asks for compliance. A regulator asks a hard question. Or worse, a near miss happens, and now you are trying to bolt safety onto a system that was never shaped for it.

This article is about the mistakes that create that moment.

Not the obvious ones like “don’t remove the e-stop.” The real mistakes. The quiet ones. The ones that look like normal engineering decisions until you try to certify, deploy, or sell at scale.

And if you are building an AI-driven robot, you have one more layer of risk: learning systems and probabilistic behavior. That does not mean you cannot build safely. It means you must be clear about what parts are allowed to be “smart,” and what parts must be boring, strict, and provable.

One more thing before we get tactical: functional safety is also a business move.

When you can show clear safety logic, clear tests, and clear documents, you sell faster. You spend less time in long customer reviews. You reduce legal risk. You lower insurance friction. You build trust. You also turn part of your design into protectable know-how. The way you detect hazards, limit motion, and recover from faults can become real IP.

That is why Tran.vc exists. We invest up to $50,000 worth of in-kind patent and IP services for robotics, AI, and deep tech startups. If you are building a robot and you want to turn your safety methods into defensible assets while you build a product that customers can say “yes” to, you can apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Now, let’s start where teams go wrong.

Most teams treat functional safety like a checklist. They ask, “What standard do we need?” Then they try to map their product onto a standard late in the build. That approach almost always hurts. Not because standards are bad. Standards are useful. The issue is timing. If safety is not part of your system design from the first real prototype, you will end up rewriting major parts under stress. You will also miss the simple, cheap choices that make safety easier.

A better way is to treat functional safety as three connected systems:

First, the robot must detect danger.

Second, it must decide what safe action to take.

Third, it must prove that action works under faults.

If any one of these is weak, the whole thing is weak.

Teams often overbuild the first part. They add sensors. They add more sensors. They add expensive sensors. But they do not build the second part with the same care. They rely on one software thread, one compute board, one “main loop.” Or they build safety behavior inside the same code that does planning and control. So when the fancy part fails, the safety part fails with it.

A simple principle: your safety path should not depend on the same fragile parts that cause the hazard.

If your robot can hit someone because the planner makes a bad choice, your safety stop should not require the planner to agree.

If your robot can run away because a CAN message is wrong, your stop should not require that bus to be healthy.

If your robot can swing a heavy arm because a vision model misreads a person, your protective behavior should not require that model to be correct.

That is the core idea that many teams miss. They build one “brain,” and they put everything inside it.

Functional safety often requires at least one independent layer that is simpler than the main brain, and that can take control when things go wrong.

Now, here is a very common failure pattern.

A team builds a mobile robot. It has lidar for mapping, cameras for perception, and a control stack that runs on a single computer. They add an emergency stop button that cuts motor power. They also add a “soft stop” in software that triggers if lidar sees an obstacle too close.

In the lab, it works. In a warehouse, it behaves oddly around reflective wrap, glass, and black surfaces. Sometimes the lidar returns noisy data. The obstacle check flickers. The team adds filters. Now it misses a pallet edge. The robot bumps. No injury. But the customer is worried.

Then the team adds another rule: if the vision model sees a human, slow down.

That seems good. But what if the vision model is down? Or the camera cable is loose? Or the GPU process crashes? If the robot still moves at full speed when the model is dead, you do not have a safety feature. You have a convenience feature that works only when the world is perfect.

Functional safety asks a harsh question: what does the robot do when it cannot trust itself?

Many teams have no defined answer. They say, “We’ll log an error.” They say, “We’ll restart the node.” They say, “We’ll alert the operator.”

Those are not safety actions. Those are support actions.

A safety action is something the robot does right now to reduce harm. It could be a stop. It could be a slow-down. It could be a controlled retreat. It could be a move to a safe pose. But it must be tied to hazards, and it must work even during faults.

Here is where it gets practical.

If you want a robot to be safe, you must write down the hazards early. Not as a huge document. Just as clear statements. “The robot can strike a person.” “The robot can pinch fingers in the gripper.” “The robot can crush a foot.” “The robot can topple and hit someone.” “The robot can drop a load.” “The robot can move when someone expects it to be still.” These are hazards. Then you ask, “What causes this hazard?” and “What prevents it?” and “What happens when prevention fails?”

When teams skip this, they build protection in random places. They add features that feel safe but are not linked to real failure modes. They end up with a robot that is complex but still fragile.

Another place teams go wrong is mixing up “safe state” with “power off.”

Power off is not always safe.

If you cut power to a robot arm holding a heavy part over a workspace, gravity takes over. That can be unsafe. If you cut power to a mobile base on a slope, it can roll. That can be unsafe. If you cut power to a robot in the middle of a narrow aisle, you may block an exit. That can be unsafe.

So “safe state” must be defined for your robot and your use case. It could mean brakes engaged. It could mean controlled stop with torque held. It could mean lowering a load. It could mean moving to a parking zone. It could mean stopping and turning on a light and sound.

A team that does not define safe state early will have endless debates later. Worse, they may pick the wrong default action and learn it only after a scary event.

Functional safety also fails when teams depend on a single sensor for a critical limit.

For example, they rely on wheel encoders for speed, and they enforce speed limits based on that. But if an encoder slips, breaks, or reads wrong, the robot can move faster than expected while the “speed limit” says it is slow.

Or they rely on a single joint position sensor to prevent overtravel. If it drifts, you can hit a hard stop at full torque.

In safety, a single point of failure is a red flag when the risk is high. That does not always mean you need two of everything. It means you must decide where you need redundancy, where you need monitoring, and where you need mechanical limits.

This is where many robotics teams waste money.

They buy redundant sensors without thinking through the failure they are trying to cover. Two bad sensors do not make one good system if both can fail the same way. If both are the same model with the same weakness, you might double cost and still be blind.

A better approach is to use diversity when it matters. If a joint angle is critical, you might use an absolute sensor plus a different method like motor current signature checks or end-stop feedback, depending on the design. If speed is critical, you might cross-check encoder speed against IMU or lidar odometry, and if they disagree beyond a threshold, you reduce power.

Even more important: many hazards are best solved with physical design, not code.

Code is flexible. Code is also easy to break. A mechanical hard stop never forgets. A guard never crashes. A compliant joint can limit force even when software is wrong.

Teams that treat safety as “software rules” tend to struggle. Teams that combine mechanical limits, simple electrical interlocks, and clean software checks tend to pass audits faster and sleep better.

Now let’s talk about the biggest modern trap: using AI as part of the safety function.

A lot of teams use a neural model to detect humans, gestures, hazards, or safe zones. That can be useful. But it is risky to make a probabilistic model the only gate between motion and a person.

You can absolutely use AI to improve safety behavior, like slowing near people or picking safer paths. But if you need a function to be dependable under a wide range of conditions, you should not make its core decision depend on a model that can fail in strange ways. At minimum, you need a fallback that is simple and testable.

Think of it like this: AI can be your helpful advisor. Your safety layer must be your strict judge.

In practice, that can look like a speed and separation monitor that uses lidar or depth sensing for hard limits, while the AI model adds context. If AI says “human,” you slow earlier. If AI is silent, you still obey the hard distance limits. If the distance sensor is degraded, you move to a safe state. The robot never relies on “smart” alone.

Another place teams go wrong is choosing the wrong metric for risk.

They talk about accuracy. They talk about uptime. They talk about mean time between failure. Those matter. Safety asks different questions. It asks, “How bad is the harm if we fail?” and “How often can that happen?” and “Can we detect it?” and “Can we control it?”

A robot that fails once a year can still be unsafe if that one failure can break a bone. A robot that fails once a week can be safe if it fails in a harmless way and always goes to safe state.

So when you design safety, you are designing the failure shape. You are shaping how the robot fails.

That means you must practice failure on purpose.

Many teams only test nominal behavior. They run happy paths. They do basic obstacle tests. They might test the e-stop. But they do not test “sensor returns junk,” “compute freezes,” “thread deadlocks,” “wheel slips,” “joint encoder drifts,” “wire harness intermittent,” “battery sag,” “network delay,” “time sync breaks,” “map is wrong,” “operator pushes robot,” “person steps into blind spot,” “sunlight blinds camera,” “dust covers lidar.”

The teams that win treat fault injection as normal. They build a small set of repeatable fault tests, and they run them every week. They do not need a big lab. They need discipline.

One simple tactic: keep a “fault box” list and try one fault per day. Unplug a sensor. Add latency. Corrupt a message. Force a NaN into a control value. Kill a process. Freeze the CPU for half a second. Then watch what happens. If the robot does not move to a safe state, you found a real gap.

When you do this early, you can fix things with small changes. When you do it late, fixes become rewrites.

There is also a documentation trap.

Some teams think documentation is “for certification.” They wait. Then they scramble to write a safety story after the robot exists. That is painful because you will discover you cannot honestly claim certain controls exist.

If you write basic safety notes as you build, you create leverage. Not pages of fluff. Just clear records: what hazards you considered, what safety functions you designed, what faults you tested, what limits you enforce, and how you know they work.

That record becomes a sales tool. It also becomes a foundation for IP.

If your team invents a novel method for detecting a failure, limiting force, or making a safe stop smoother without losing throughput, that is patentable in many cases. It can also be a trade secret if you keep it tight. Either way, it is an asset.

This is a key point: safety work is not only cost. It can become your moat.

If you build a robot that can run close to people with higher uptime and lower risk because your safety system is well designed, you have a market edge. If you can prove it, you win more deals.

That is why Tran.vc’s model fits robotics teams. We invest in your defensibility early. We help you turn real engineering into protectable IP. We help you build a plan that investors and customers take seriously. If you are building robotics or AI and want to protect what matters while you ship faster with less risk, you can apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Functional Safety for Robotics: Where Teams Go Wrong

Why teams push safety to “later”

Functional safety often gets treated like a chore you do after the robot works. The demo is running, the pilot is close, and everyone is racing to show motion, speed, and smooth autonomy. In that rush, safety feels like something that can wait. The problem is that waiting changes your cost. Once the stack is built, safety becomes a rewrite instead of a design choice.

This is why teams get stuck. They do not “ignore” safety. They simply build without shaping the system around it. Then, when a customer asks for proof, the team scrambles to create a story that matches what the robot already does. That story is almost never clean.

What functional safety really means in a robotics team

Functional safety is not the emergency stop button. It is not a few rules in the code. It is the method you use to make sure the robot reduces harm when things go wrong. That includes sensor faults, compute crashes, broken cables, software bugs, wrong maps, bad updates, and unexpected human behavior.

If you want a simple way to think about it, functional safety is about controlled failure. You cannot promise “no failures.” You can promise that when failure happens, the robot behaves in a safer way than it otherwise would. That promise must be backed by design and tests, not hope.

Why this is also a business problem

Safety is a speed lever in the real world. Buyers do not just want a robot that works; they want a robot that does not put their people at risk. Insurers, partners, and customer safety teams will ask for evidence. If you cannot show clear safety logic and clear test results, sales cycles slow down, and deals shrink.

There is also a product angle. When your robot is safer by design, you can enter more sites, run closer to people, and get approved faster. That is a real competitive edge. It can also become protectable know-how, which is where IP and patents can matter.

Where Tran.vc fits into this story

Many teams do real safety engineering and never turn it into an asset. They build smart fault checks, safe stop methods, limit logic, and recovery behavior, but they do not capture it as IP. Tran.vc helps robotics, AI, and deep tech teams do that early, while the product is still forming, and while the choices are still flexible.

Tran.vc invests up to $50,000 worth of in-kind patent and IP services. If you are building robotics and you want to protect what makes you defensible, you can apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Mistake #1: Treating safety like a checklist

The “we’ll match a standard later” trap

A very common pattern is picking a safety standard late and trying to map the robot onto it when a customer asks. That feels practical, but it usually creates pain. You discover that your architecture does not support independent safety behavior. You find that key signals are not monitored. You realize your stop behavior depends on the same compute that can crash.

When this happens, the team burns months doing rework that could have been avoided with a few early choices. Safety becomes a fire drill. Engineering becomes reactive. The product roadmap gets pushed back, and morale takes a hit because the work feels like “undoing” progress.

What to do instead from day one

The better approach is to design around a small set of safety questions early. What are the hazards? What is the safe state? What triggers a move to that safe state? How does the robot detect that it cannot trust its own senses? What happens if the main computer freezes?

You do not need a huge document to start. You need a clear, shared method. When the whole team uses the same method, safety decisions stop feeling random. They become part of everyday engineering.

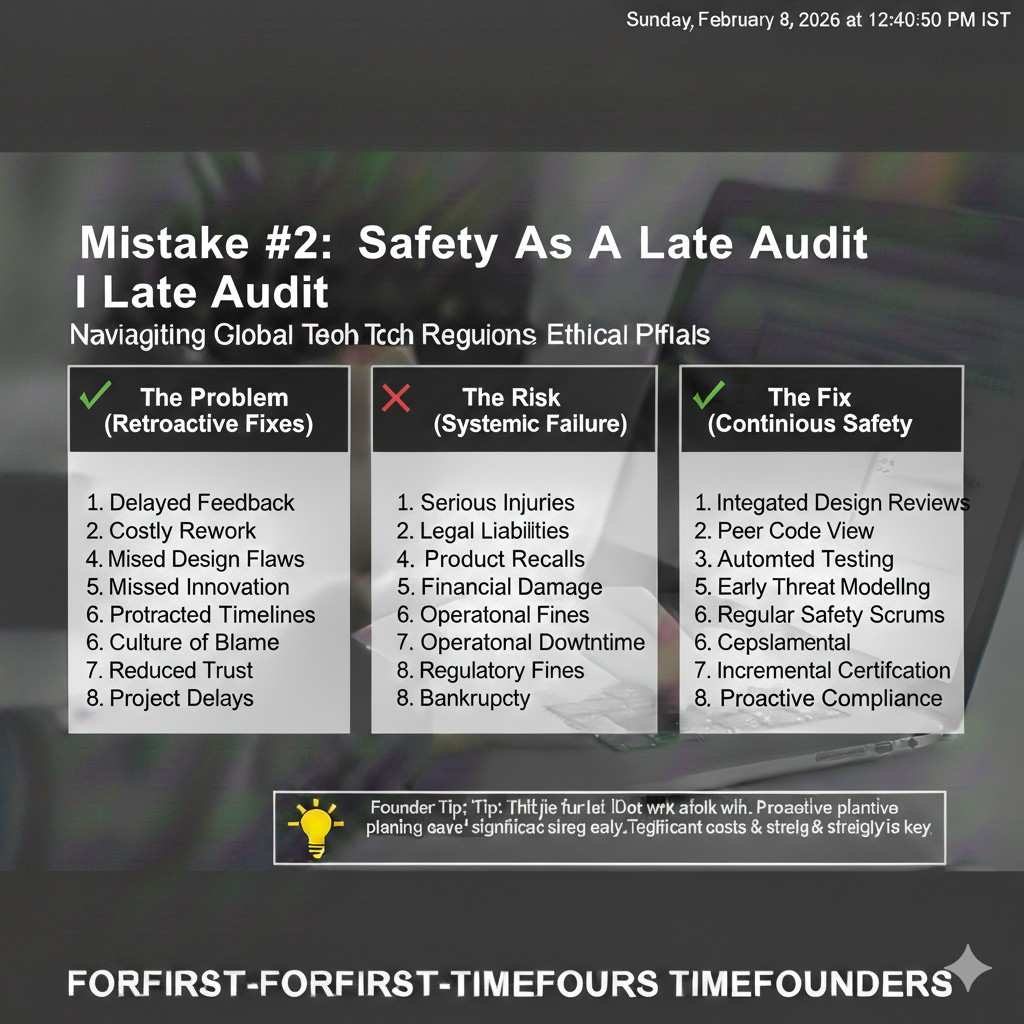

Make safety part of normal review, not a late audit

Teams that succeed treat safety like performance or reliability. It is part of design review, part of test plans, and part of release checks. That does not mean slowing down. It means making fewer expensive changes later.

When safety is built into normal review, you avoid the worst outcome: a robot that works in the lab but cannot be deployed because no one can prove it is safe when faults happen.

Mistake #2: Building one “brain” and putting safety inside it

Why “one stack” feels clean but fails under faults

Robotics teams like clean stacks. One compute box, one main loop, one set of nodes, one planner and controller pipeline. It feels elegant, and it is easy to iterate. But if your safety behavior lives in the same place as your autonomy behavior, a single fault can take both down.

That is not a theoretical risk. A compute spike, a memory leak, a deadlock, a driver crash, a timing bug, or a power brownout can hit the main stack. If the same stack must also detect danger and stop motion, you have a single point of failure.

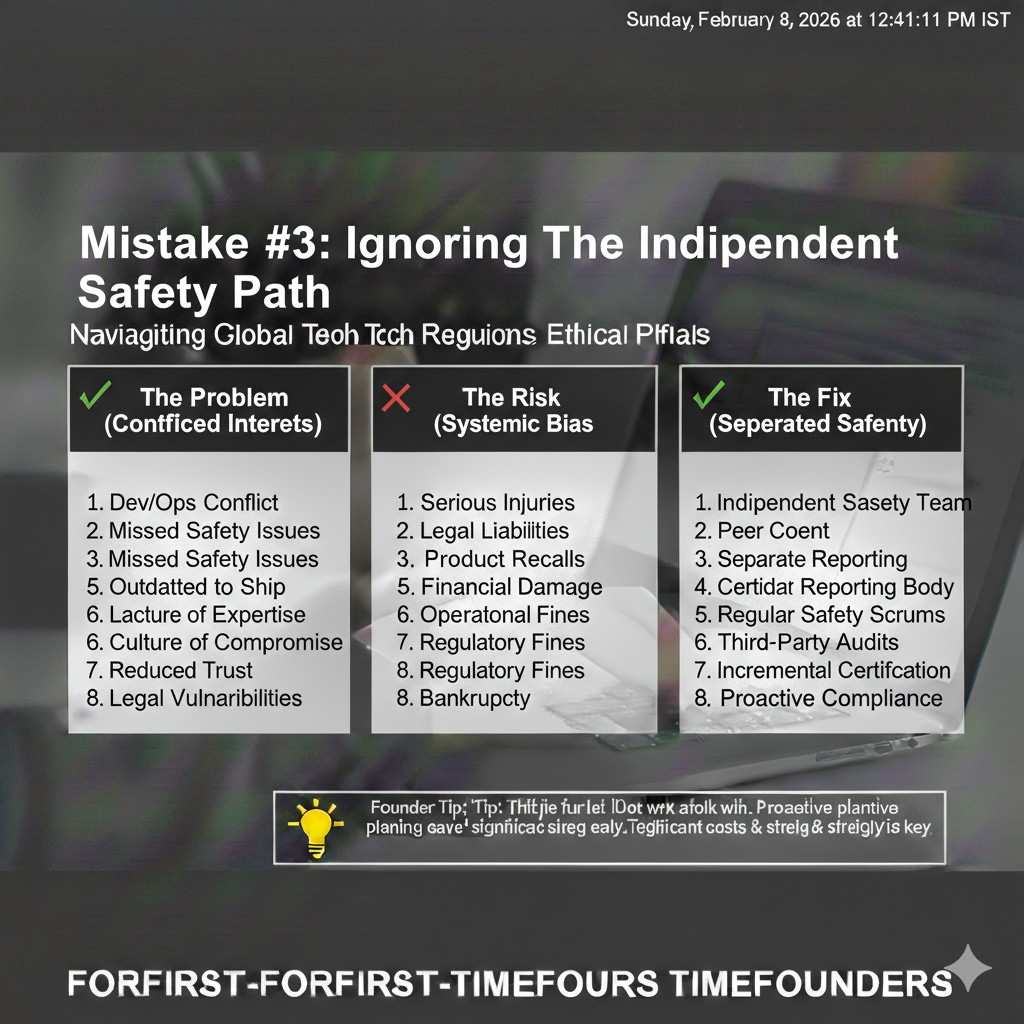

The idea of an independent safety path

A safer design uses at least one independent layer that is simpler than the main autonomy. This layer watches key signals and can force a safe action when limits are crossed or when the main stack is unhealthy. Simple does not mean “dumb.” It means easy to test and hard to break.

Independence can come in different forms. It might be a separate microcontroller, a safety-rated controller, a dedicated board that monitors speed and proximity, or a hardware interlock that cuts power in a controlled way. The point is that safety does not ask the main brain for permission.

How to decide what must be independent

Not everything needs redundancy. Independence should be reserved for the hazards with real harm potential. Start by identifying what could cause injury or major property damage. Then find the parts of your system that, if they fail, could directly lead to that harm.

If a single failure can lead to a dangerous motion, the safety response should not require the same component to be healthy. That is the core logic. It keeps your safety system from collapsing with the rest of the stack.

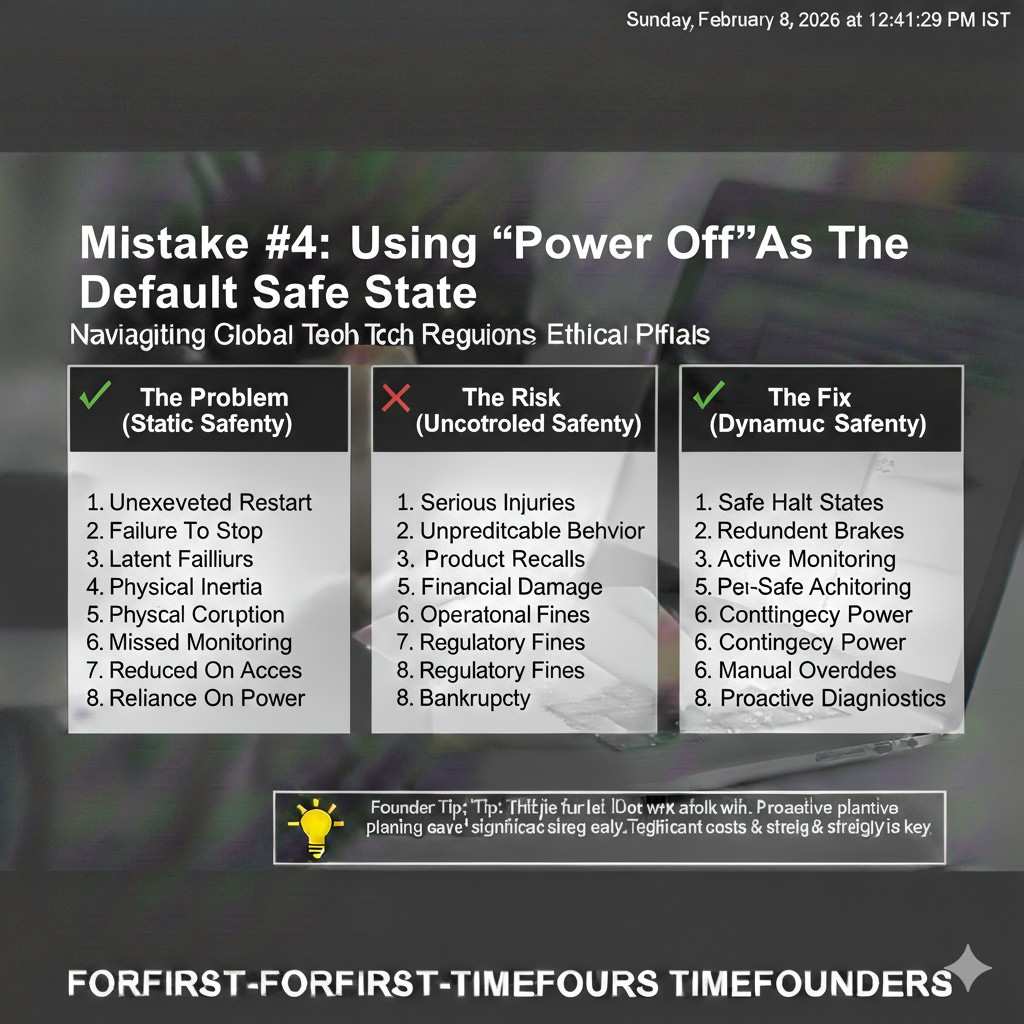

Mistake #3: Using “power off” as the default safe state

Safe state is not always “motors off”

Cutting motor power is sometimes safe, but not always. If a robot arm is holding something heavy, power off can drop a load. If the base is on a slope, power off can allow rolling. If a robot has a spring or stored energy, power off can release it in a way you did not plan.

This is why safe state must be defined for your product and your site. “Stop” is not one thing. A safe stop can mean brakes engaged, torque held, moving to a stable pose, lowering a load, or backing away to a known safe zone.

Define safe state for each hazard, not just for the robot

Different hazards can require different actions. For collision risk, a controlled stop with a speed limit might be best. For a tip-over risk, lowering the center of mass might matter. For a gripper pinch hazard, opening the gripper or removing force might be safer than freezing motion.

If you do not define these behaviors early, your team will argue later under pressure. Worse, you may ship the wrong default stop and only learn it after a close call.

Make safe state observable to humans nearby

A safe state should be visible. People around the robot need to understand what is happening. Lights, sound, and clear indicators reduce confusion. Confusion leads to risky behavior, like walking into a robot that is about to recover from a fault.

Making safe state visible is not only a safety decision. It is also a trust decision. Operators and site owners feel more comfortable when the robot communicates clearly.

Mistake #4: Relying on a single sensor for a critical limit

Single-sensor dependency creates silent failure

Teams often enforce a key safety limit based on one sensor. Speed based on wheel encoders. Position limits based on a single joint sensor. Obstacle distance based on one lidar. The issue is not that these sensors are bad. The issue is that sensors fail in quiet ways.

An encoder can slip, a magnet can weaken, a connector can loosen, or a noise issue can cause drift. If your limit logic trusts a single sensor, you may not notice it is lying until the robot behaves dangerously.

Redundancy is not “two of the same thing”

Some teams respond by adding a second identical sensor. That can help, but it can also be a false comfort. Two identical sensors can fail the same way in the same environment. If a lidar struggles with reflective surfaces, adding another similar lidar may not solve the core risk.

Where it matters, you want diversity. Different sensing methods, different failure modes, and cross-check logic that can detect disagreement. The goal is not perfection. The goal is detection and safer behavior when uncertainty rises.

Use physical design to reduce what sensors must guarantee

The most effective safety choices are often mechanical. Hard stops prevent overtravel even if software fails. Guards and covers prevent access to pinch points. Compliance can limit force. Brakes can hold a safe pose without relying on continuous control.

When the physical design carries part of the safety burden, your software becomes less stressed. You also reduce the number of “must never fail” components, which makes the entire system easier to prove.

Mistake #5: Making AI the safety gate

AI is helpful, but it is not predictable enough to be the only guard

AI models can detect people, recognize zones, and predict motion. That is valuable. The risk is using AI as the only barrier between a moving robot and a human. AI can fail in ways that are hard to predict, especially when lighting changes, clothing differs, or the camera is dirty.

If your robot only slows down when a vision model says “human,” you have a safety feature that depends on the model being perfect. That is not a stable promise to make in real sites.

Put AI in the “advice” role, not the “permission” role

A safer pattern is to have a strict, testable safety layer that enforces hard limits. Then AI can enhance behavior inside those limits. If AI sees a human, the robot can slow earlier. If AI does not see a human, the robot still obeys speed and distance rules based on more direct measures.

This design keeps the robot safe even when AI is wrong or offline. It also makes testing easier because the safety layer has simple inputs and simple outputs.

Plan for AI faults like you plan for sensor faults

AI faults include crashes, slow inference, stale frames, wrong time stamps, and degraded accuracy. Treat these like normal failure modes. Decide what the robot does when the AI pipeline is unhealthy. If the robot continues at full speed with a dead model, the system is not designed for real-world safety.

Healthy systems treat uncertainty as a reason to reduce risk. That can mean slowing down, increasing clearance, or moving to a safe state until confidence returns.

Mistake #6: Testing only “happy paths” and skipping fault tests

Most safety failures show up only under faults

A robot can look perfect in normal runs and still be unsafe. Many dangerous cases appear only when something degrades. A sensor returns noisy data. A process restarts at the wrong time. A network delay causes stale commands. A time sync issue makes control behave oddly. A battery sag causes brownouts.

If you do not test these conditions, you will learn about them at the worst time: during customer deployment, or after a near miss.

Make fault injection normal, not special

You do not need a big lab to do fault tests. You need repeatable habits. Unplug a sensor and watch behavior. Kill a process and see if the robot moves to a safe state. Add latency and check if stale commands are blocked. Force a bad value and ensure it is rejected.

The goal is to build trust in your safety response. If your robot always reduces risk when parts misbehave, your team can ship with more confidence and fewer surprises.

Turn faults into a steady improvement loop

When you find a fault gap, do not patch it once and move on. Write a simple test that reproduces it. Add it to a regular test set. Run it before releases. This is how safety becomes stable over time instead of being a one-time push.

This also creates proof. Proof matters in buyer reviews. Proof also matters if you ever need to show due care after an incident.

Mistake #7: Treating documentation as “bureaucracy”

Documentation is your memory, not your burden

Many teams think documentation is only for certification later. Then they are forced to recreate decisions months after the fact. That is stressful and error-prone. People forget why choices were made. Tests were run but never recorded. Hazards were discussed but not captured.

Good documentation is not long. It is clear. It lets you answer customer questions without panic. It also keeps safety from becoming a personality-based process where only one person “knows the truth.”

Document the minimum that gives you leverage

What hazards did you consider? What safety functions address them? What triggers a safe action? What is the safe state? What faults did you test? What were the results? What evidence do you have that the robot behaves safely under those faults?

When you can answer those questions simply, you look mature. You reduce sales friction. You also make it easier to train new hires and scale the engineering team.

Documentation can become defensible IP

If your team designs a unique method for safe stops, fault detection, or safer shared workspace behavior, that can be protectable. Many robotics teams build valuable safety know-how without realizing it. Capturing it early creates options: patents, trade secrets, or a clear technical advantage you can defend.

Tran.vc helps teams turn real engineering into real assets. If you want help protecting what you build while staying lean, apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Next up: the hard, practical failure points inside real robot stacks

What we will cover next

In the next section, I will go into the gritty issues that cause real-world safety failures. We will talk about why e-stops get wired in ways that look fine but fail audits, how “soft limits” break when time sync drifts, why safety logic gets bypassed during debugging and never fully restored, and how to design a safety layer that stays simple as the product grows.

Why this matters for early-stage teams

Early teams cannot afford a long redesign right before deployment. The goal is to make small, early choices that keep you from getting trapped later. When safety is part of architecture, you move faster in the long run, even if it feels like extra work today.

A quick reminder on getting help

If you are building robotics, AI, or deep tech and you want to build a defensible foundation early, Tran.vc can help through in-kind patent and IP services worth up to $50,000. You can apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/