If you build robots, you already know the hard truth: real-world data is slow, messy, risky, and expensive. Cameras get glare. Sensors drift. Warehouses change layouts. People walk into paths they shouldn’t. A robot that looks “great in the lab” can fail fast in the field.

That is why synthetic data and simulation systems have become the quiet engine behind modern robotics. Not because it is trendy, but because it works. When you can generate millions of labeled scenes overnight, you can train faster. When you can replay rare edge cases, you can fix safety issues before they hurt someone. When you can test in a digital copy of the world, you can ship with more confidence.

But here is the part many founders miss: the synthetic data pipeline and the simulator you built are not just “tools.” They can be defensible assets. They can be protected. And if you protect them the right way, they can turn into real leverage when you raise, partner, or compete.

This article is about how to think about patenting synthetic data and simulation systems for robotics in a practical way. Not theory. Not legal fluff. Just a clear path for founders who want to protect what matters.

Before we go deeper, here is the simple question this blog will help you answer: What, exactly, inside my synthetic data and simulation stack can be patented—and how do I describe it in a way that actually holds up?

If you are building robotics, AI, or a deep tech system and you want to turn your work into protectable IP early, you can apply to Tran.vc any time here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Patenting Synthetic Data and Simulation Systems for Robotics

Why synthetic data and simulation matter in robotics

Robotics is different from most software. A normal app can be tested with clicks and logs. A robot must deal with light, dust, motion, noise, people, and unsafe corners. That real world creates “long tail” cases that are hard to catch with small test sets.

Synthetic data helps because you can create the hard cases on purpose. You can change the sun angle, add blur, place objects in odd spots, or create rare failures that almost never happen in real life. Simulation helps because you can run the robot in many scenes, many times, without breaking hardware or waiting for a warehouse shift to start.

When founders talk about “our model is better,” investors often ask, “Why can’t others copy it?” A good answer is not only the model. It is the engine that feeds it. The way you generate, label, validate, and use data can be your moat.

If you want to turn that engine into a protected asset early, you can apply to Tran.vc here anytime: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

The IP mistake most robotics teams make early

Many teams treat synthetic data and simulation like internal plumbing. They build it fast, then move on. Later, they realize the pipeline is the reason they can train faster and ship safer than peers. But by then, they have already shipped public demos, published blog posts, or shared details with partners without protection.

Patents are not about bragging. They are about controlling options. A solid patent family can help you stop copycats, negotiate with partners, and look more “real” during a seed raise. It can also reduce fear during enterprise sales, because customers like vendors that can defend their tech.

The goal is not to patent “synthetic data” as a broad idea. The goal is to patent your specific system that does something new, in a way others can’t easily work around.

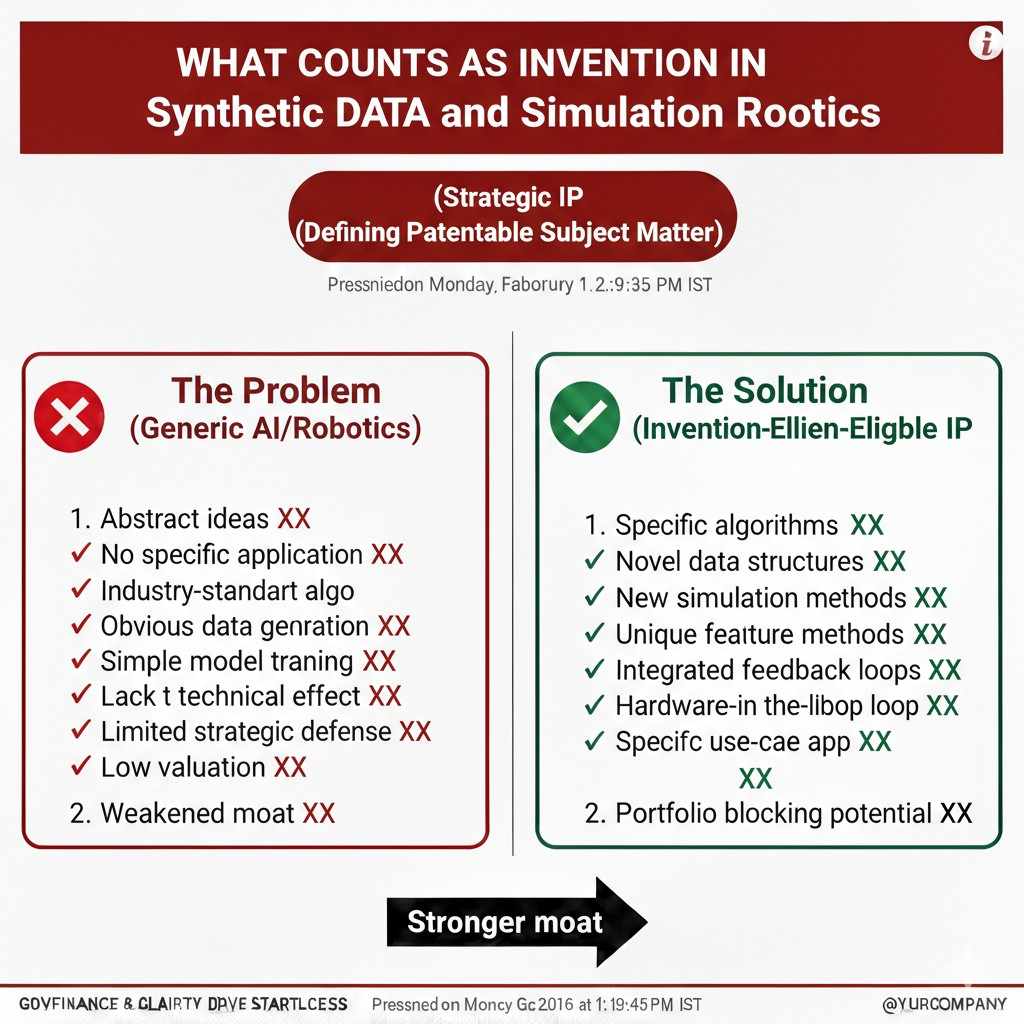

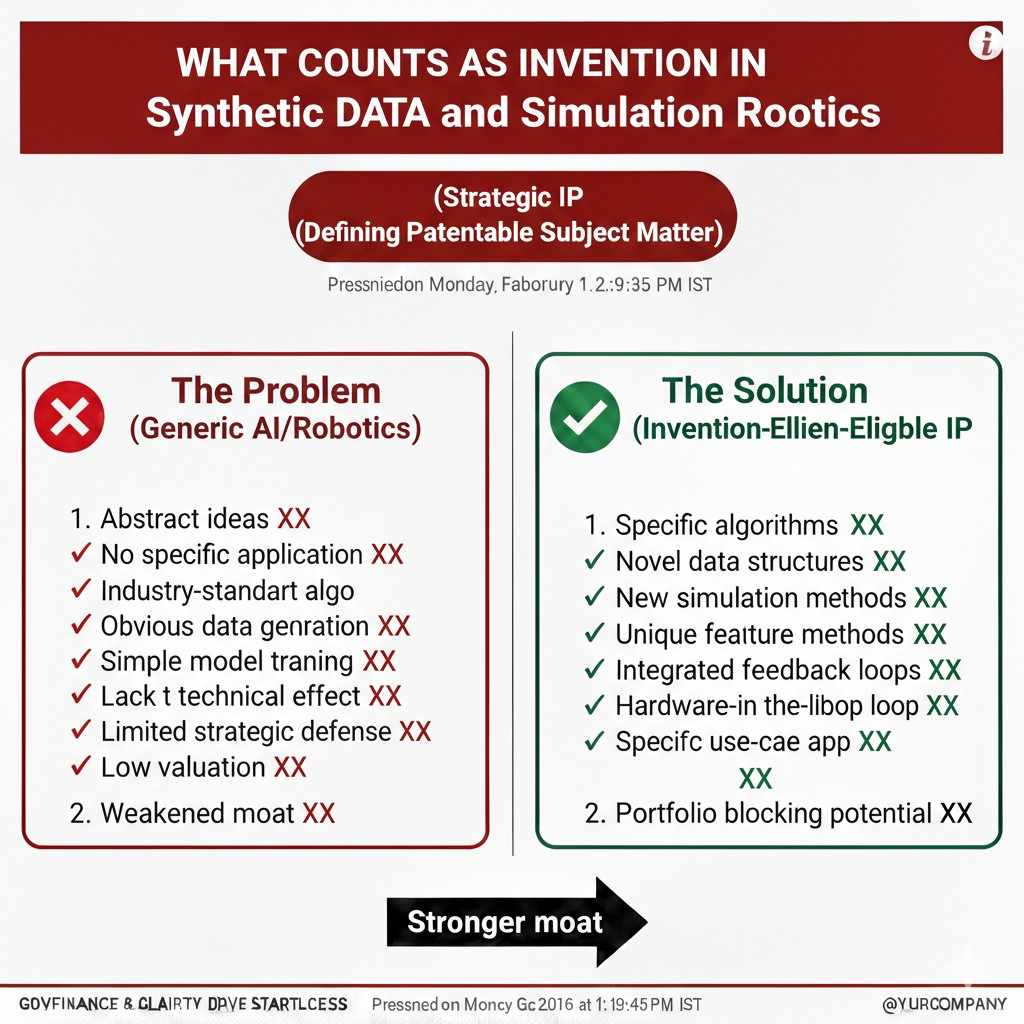

What counts as an invention in synthetic data and simulation

The difference between a concept and a patentable system

A concept is “we use simulation to train our robot.” That is too broad. A patentable system is a specific method that changes results in a measurable way. It has steps, structure, and a clear technical effect.

Think like an engineer, not like a marketer. What did you build that is repeatable and could be written as a process another team would struggle to recreate without your notes?

If you can describe it as: “When we do X, the robot improves in Y way, because Z is handled differently,” you are closer to something patentable.

Where patents usually live in a synthetic data pipeline

Synthetic data is not one thing. It is a chain. In robotics, that chain often includes world creation, scene randomization, sensor modeling, label creation, quality checks, and training integration.

The patentable parts usually show up where you solved a hard technical problem. For example, you may have built a better way to keep labels correct when objects are occluded. Or you may have built a way to generate scenes that match a real warehouse without scanning every shelf.

The key is not “we generate data.” The key is “we generate data in a way that produces a better robot, with less real-world collection, while keeping safety and accuracy.”

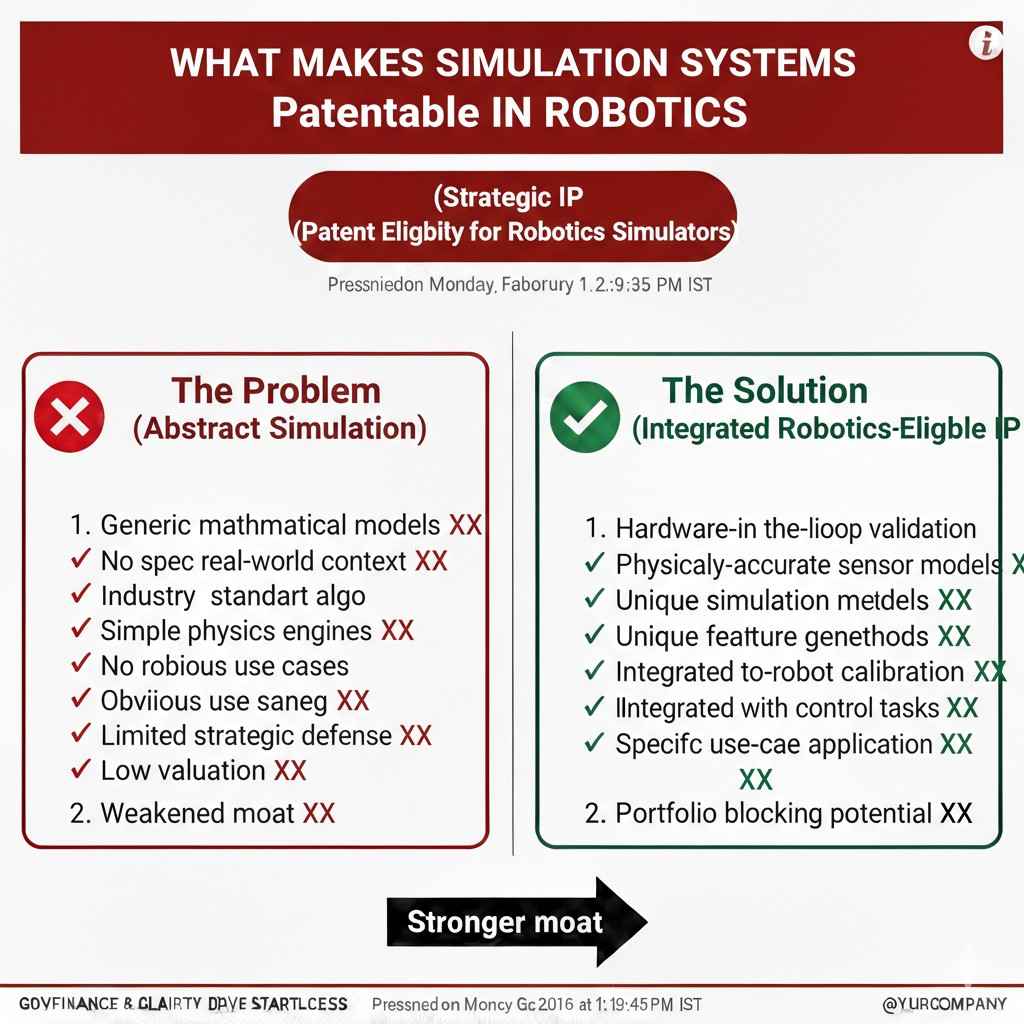

What makes simulation systems patentable in robotics

A simulation system can be patentable when it goes beyond a standard game engine setup. If your simulator is tied to robotics control, physics, sensors, timing, and safety logic, there are many places where new inventions happen.

Some examples of inventions in simulation systems include how you sync sensor streams, how you emulate failure modes, how you do domain randomization without breaking physical realism, or how you use sim results to adjust policies in a stable way.

In plain words, patents often protect the “how” that leads to reliable learning and safer deployment.

The main subjects you can patent in this space

Subject 1: Synthetic data generation methods

This subject is about how you create the scenes and the data. Not the training model itself, but the system that outputs inputs to the model.

A strong invention here usually describes how the generator picks scenes, varies them, and ensures they are useful. The more your system adapts to the robot’s weaknesses, the more valuable it becomes. For example, if your generator notices that the robot fails on shiny objects, and then creates more shiny-object scenes with controlled variation, that can be a clear technical improvement.

Patent claims in this area often focus on the steps used to create datasets that are both diverse and targeted, without needing endless human work.

Subject 2: Labeling, annotation, and ground-truth creation

In robotics, labels are expensive because they must be correct. A wrong label can teach a robot the wrong thing, and that can become a safety problem.

If you built a system that creates labels automatically in simulation, you likely also built rules to keep those labels consistent when objects overlap, when the camera moves, or when depth sensors produce noise.

This subject is often patentable because it is not just “we label it.” It is “we label it under tough conditions, and we can prove the labels remain valid.” That proof step is important. It shows technical care and can help your patent look stronger.

Subject 3: Domain gap reduction and sim-to-real transfer systems

This subject is about reducing the gap between simulated data and real-world data. Many robots fail because the sim looks clean, while reality is dirty.

If your system uses a method to match sim output to real sensor behavior, that can be patentable. The invention may be in how you model noise, how you calibrate the sim using small samples of real data, or how you blend real and synthetic data during training.

The biggest signal here is a measurable effect, such as higher success rate in a real warehouse after training with your pipeline, using fewer real-world runs.

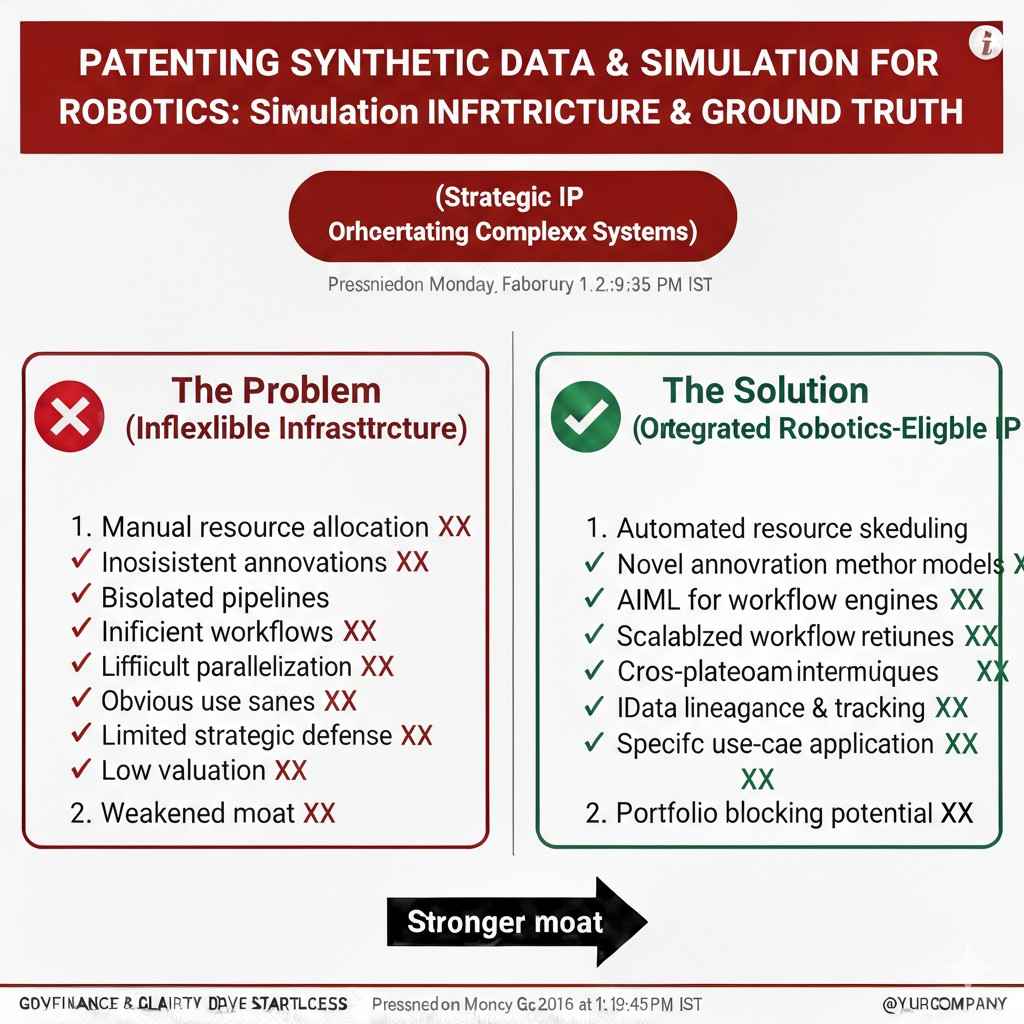

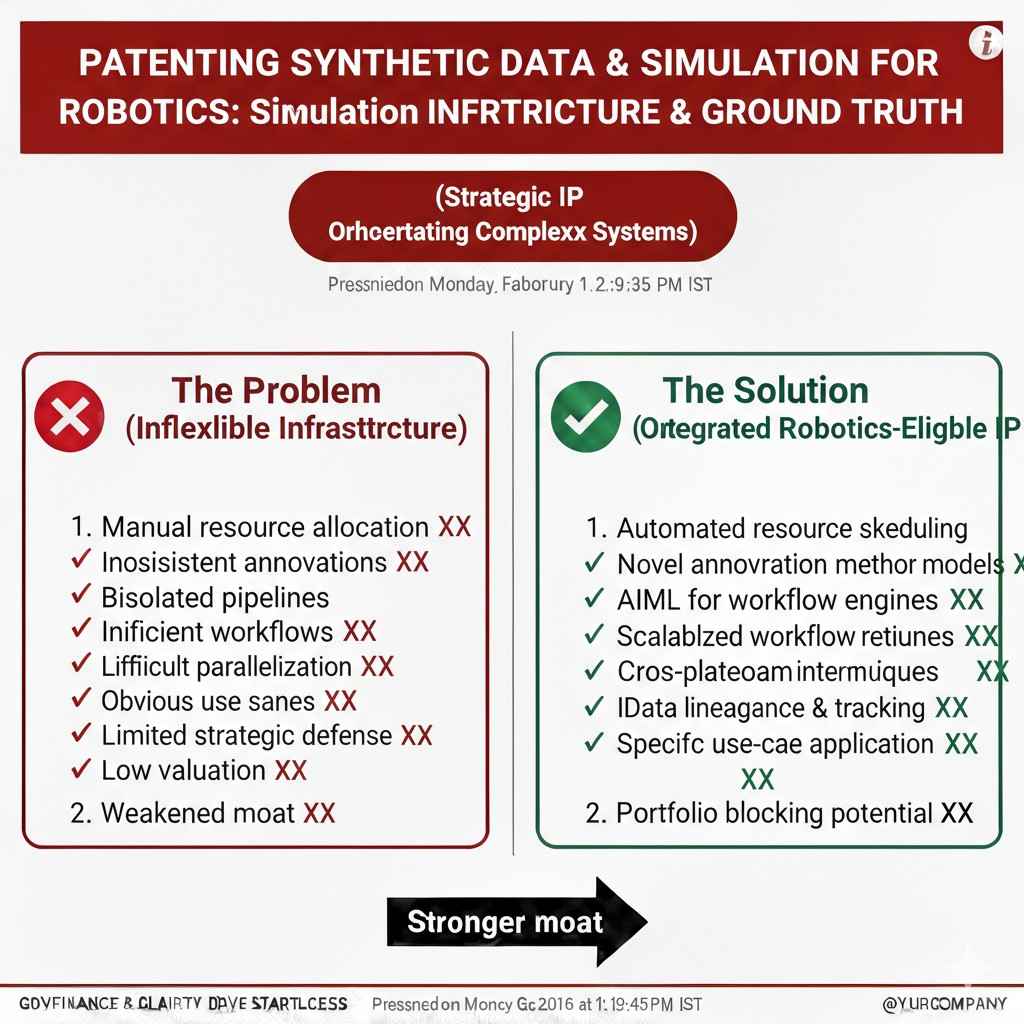

Subject 4: Simulation infrastructure and orchestration

This subject is about the platform layer. How you run simulation at scale, how you schedule scenarios, how you track versions, and how you decide what to run next.

This is often overlooked, but it matters. If you have built a system that picks test cases automatically based on risk, or a system that reproduces failures with consistent seeds and logs, you may have an invention.

In robotics, reproducibility is hard. If you solved it with a strong design, you may have something worth protecting.

Subject 5: Safety and validation inside simulation

Many robotics teams use simulation to test safety rules, collision handling, and emergency behaviors. If you built a system that uses simulation not just to test, but to prove safety thresholds or to catch rare hazards, that can be patentable.

For example, you might simulate near-miss scenarios and measure safety margins. Or you might create “adversarial” agents that behave unpredictably to stress test your planner.

Patents in this subject often highlight a technical safety benefit and a clear reduction in real-world risk.

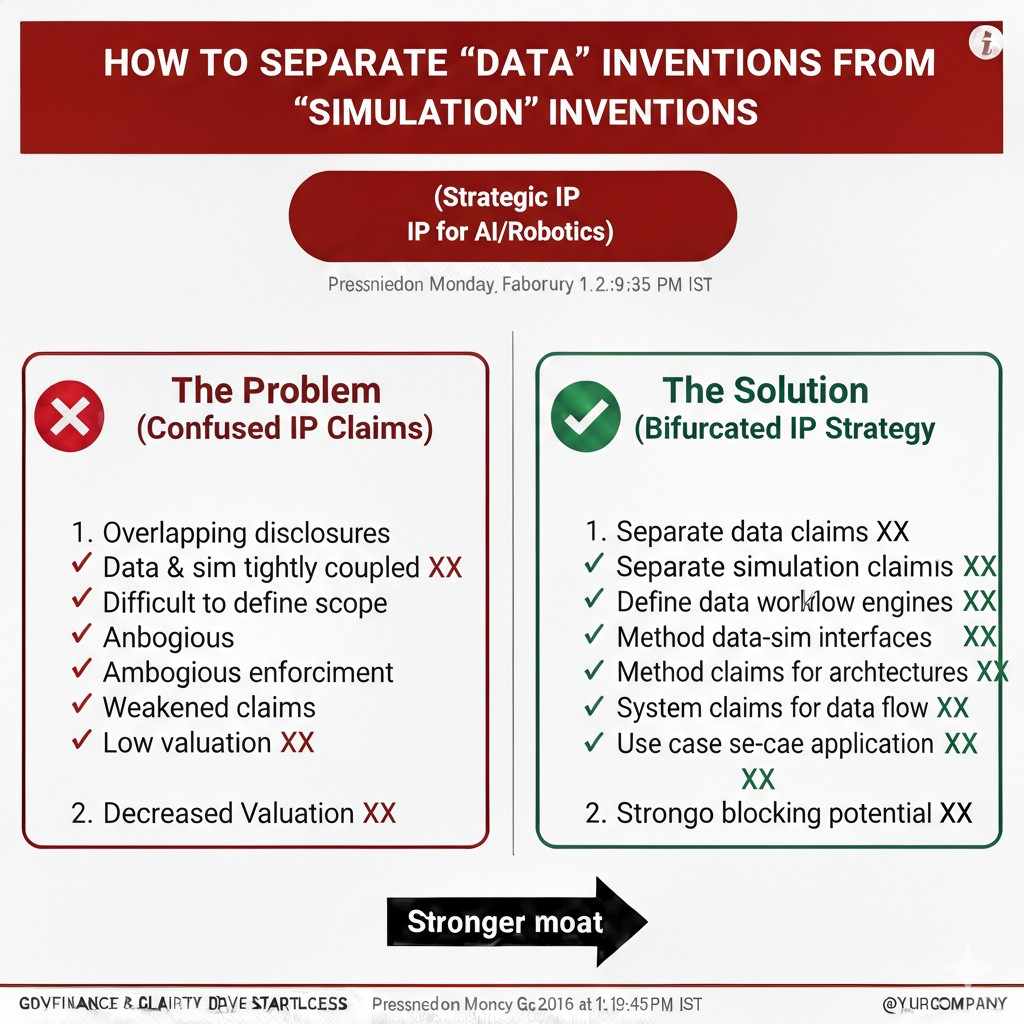

How to separate “data” inventions from “simulation” inventions

Synthetic data inventions focus on outputs used for learning

Synthetic data inventions usually focus on what gets generated and why it improves learning. The key object is the dataset, and the system steps that produce it.

If your novelty is about how scenes are composed, how labels are generated, or how data is filtered, you are likely in the synthetic data category.

A good sign is that your invention still makes sense even if the simulator is swapped, because the key is the data logic, not the physics engine.

Simulation inventions focus on the environment and system behavior

Simulation inventions usually focus on how the environment behaves and how the robot interacts with it. The key object is the simulator itself, including timing, physics, sensor models, and how scenarios are run.

If your novelty depends on high-fidelity sensors, control loop timing, or physics-based outcomes, you are likely in the simulation category.

A good sign is that your invention still matters even if the learning algorithm changes, because the key is the simulation method, not the model architecture.

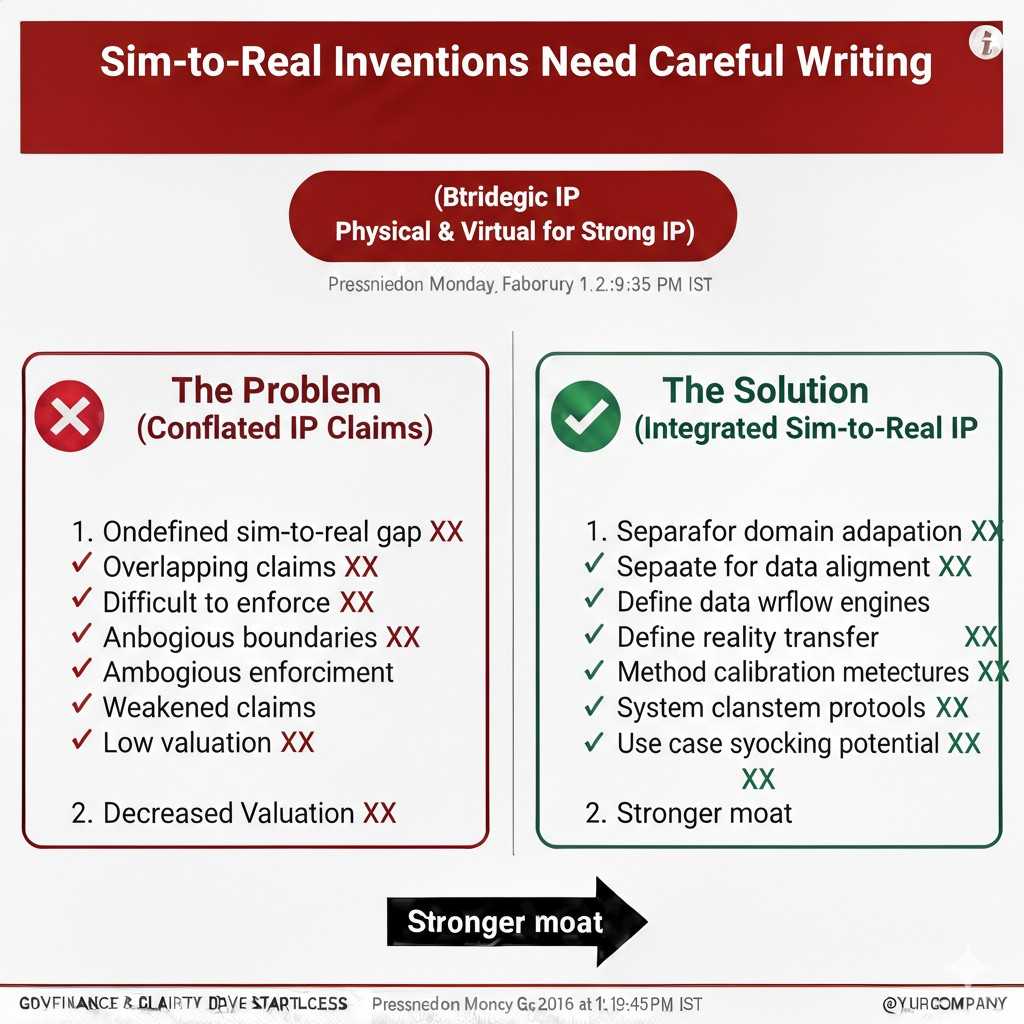

Sim-to-real inventions sit between both, and need careful writing

Sim-to-real is often a blend. The simulator is used to create data, but the core value is the bridge to real performance. This is where many patents fail if they are written too vaguely.

When writing patents here, you want to be clear about what is being measured in the real world, how the system adjusts, and what feedback loop is used. The more you can explain the loop as a set of steps with inputs and outputs, the better.

If you want expert help turning these ideas into a clean patent strategy, Tran.vc supports technical founders with up to $50,000 in-kind IP and patent services. You can apply anytime here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

What makes a strong patent in this area

Specificity wins, because broad claims get rejected

A common founder instinct is to aim for the widest patent possible. The problem is that examiners see “synthetic data” and “simulation” all day now. Vague claims get pushed back fast.

A stronger path is to pick the parts you truly built that are different. Then describe them in a way that is hard to copy without copying your steps.

You can still get wide protection, but it comes from well-chosen details that can be generalized, not from empty broad language.

Technical effect must be clear and tied to robotics outcomes

The patent should not read like a product pitch. It should read like a method that produces a technical effect.

In robotics, technical effects can be things like better pose accuracy, fewer collisions, faster convergence during training, fewer required real-world runs, improved grasp success, or better tracking under motion blur.

If your invention reduces cost and improves safety at the same time, that is even stronger, because it shows real engineering value.

The best patents describe a system others can implement, but not easily

This is the balance. You must disclose enough to meet patent rules, but you want the “secret sauce” to be protected through claim structure.

That is why it helps to define components, data flows, and decision steps. A patent that says “use AI to generate data” is weak. A patent that says “generate scenes using a guided sampler that targets failure clusters measured in real-world validation runs, then update the sampler parameters based on error metrics” is much harder to work around.

A Practical Playbook to Patent Your Synthetic Data and Simulation Stack

Start with your real system, not with legal language

The biggest mistake founders make is starting with patent language before they understand what they truly built. You do not begin with claims. You begin with your architecture.

Open your internal docs. Look at your diagrams. Review the parts of your codebase that took the longest to get right. The invention is often hiding in the messy middle, not in the final demo.

Ask yourself a simple question. If a strong competitor hired three senior engineers, what part of our pipeline would still take them six months to reproduce? That friction point is often where the patent lives.

Map your pipeline from input to deployment

Sit down and draw your full flow. Start from the moment you define a scenario in simulation. Move through scene generation, sensor modeling, labeling, dataset assembly, model training, evaluation, and then deployment in the real robot.

As you trace this path, look for decision points. Where does the system choose one option over another? Where does it adapt based on metrics? Where does it correct itself?

Those points of logic are often stronger than static components. A patent is not just about structure. It is about controlled steps that lead to a result.

Identify the “technical leap” in your system

Every strong patent has a moment where something changes. It is the leap from “normal approach” to “our approach.”

Maybe most teams randomize scenes blindly, but you built a guided randomizer that targets error clusters found in real deployments. Maybe others use fixed noise models, but you built a dynamic sensor noise emulator that updates based on real-world calibration batches.

That leap must be clearly described. Not in marketing words, but in system steps. What is measured? What is computed? What changes because of that computation?

If you cannot point to a measurable improvement, you may need to refine the invention before filing.

Turning Engineering Notes into Patent-Ready Material

Document failure before you document success

Many teams only write about what works. But patent strength often comes from the problem you solved.

Describe what was failing before your system existed. Were robots missing small objects in low light? Were grasp attempts unstable because depth maps were too clean in simulation? Were real-world runs too costly to cover rare cases?

When you describe the technical pain clearly, it becomes easier to show how your invention fixes it. That contrast helps patent examiners understand why your method matters.

Capture metrics that prove improvement

Patents are stronger when tied to numbers, even if the claims do not include exact values.

Keep internal records that show improvement in training time, success rate, safety margin, or data efficiency. If your synthetic pipeline reduced real-world data collection by half, write that down. If your simulator caught edge cases that prevented crashes, document it.

You do not need to expose secret numbers publicly. But your patent application should reflect that the invention has real technical impact.

Create diagrams that show system flow clearly

Diagrams are not just for investors. They are powerful in patents.

Draw blocks that show how data moves. Show where feedback loops exist. Highlight modules that adjust parameters based on performance.

When a patent attorney can see your system clearly, they can write stronger claims. If the diagram is fuzzy, the patent will likely be fuzzy too.

Avoiding Common Mistakes When Patenting in This Space

Do not overfocus on the AI model itself

In many cases, the core model may not be the strongest patent target. Model architectures evolve fast. What is new today can be old next year.

Instead, focus on how the model is trained, validated, and improved through your synthetic and simulation systems. That infrastructure is often harder to replace.

Your moat is rarely just the neural network. It is the pipeline that feeds and shapes it.

Do not publish key details before filing

Blog posts, conference talks, GitHub repos, and demo videos can all count as public disclosure. In many regions, once you disclose publicly, your ability to patent can shrink or disappear.

This does not mean you should hide forever. It means you should file before you go public with the core technical details.

Timing matters. A strong IP strategy aligns product launches and public storytelling with filing dates.

Do not assume open-source tools kill patentability

Using game engines or open-source libraries does not prevent you from patenting your system. What matters is what you added on top.

If you built a new orchestration layer, a new domain adaptation loop, or a new safety validation method using those tools, that layer can still be protectable.

The patent does not need to claim the engine. It claims your unique use and method built around it.

Strategy: When to File and How Broad to Go

File when the system is stable enough to describe

You do not need a fully mature product to file a patent. But you do need a system that works in a repeatable way.

If the core logic keeps changing weekly, it may be too early. If the core flow has stabilized and improvements are now incremental, it may be the right time.

A provisional filing can give you early protection while you continue refining the system.

Think in families, not single patents

One filing is rarely enough for a serious robotics company. Synthetic data generation, simulation fidelity, sim-to-real transfer, and safety validation can each support separate patents.

Over time, these can form a family around your platform. That family becomes a signal to investors and competitors that you are building for the long term.

This is especially important in deep tech, where development cycles are longer and capital needs are higher.