Freedom to Operate: When You Need It looks at your startup, they are not only looking at your product or your team. They are also looking at what you own. Not in an ego way. In a legal and business way.

Because if you build something that works, someone will copy it. And if you cannot prove your edge is protected, your growth can turn into a price war fast.

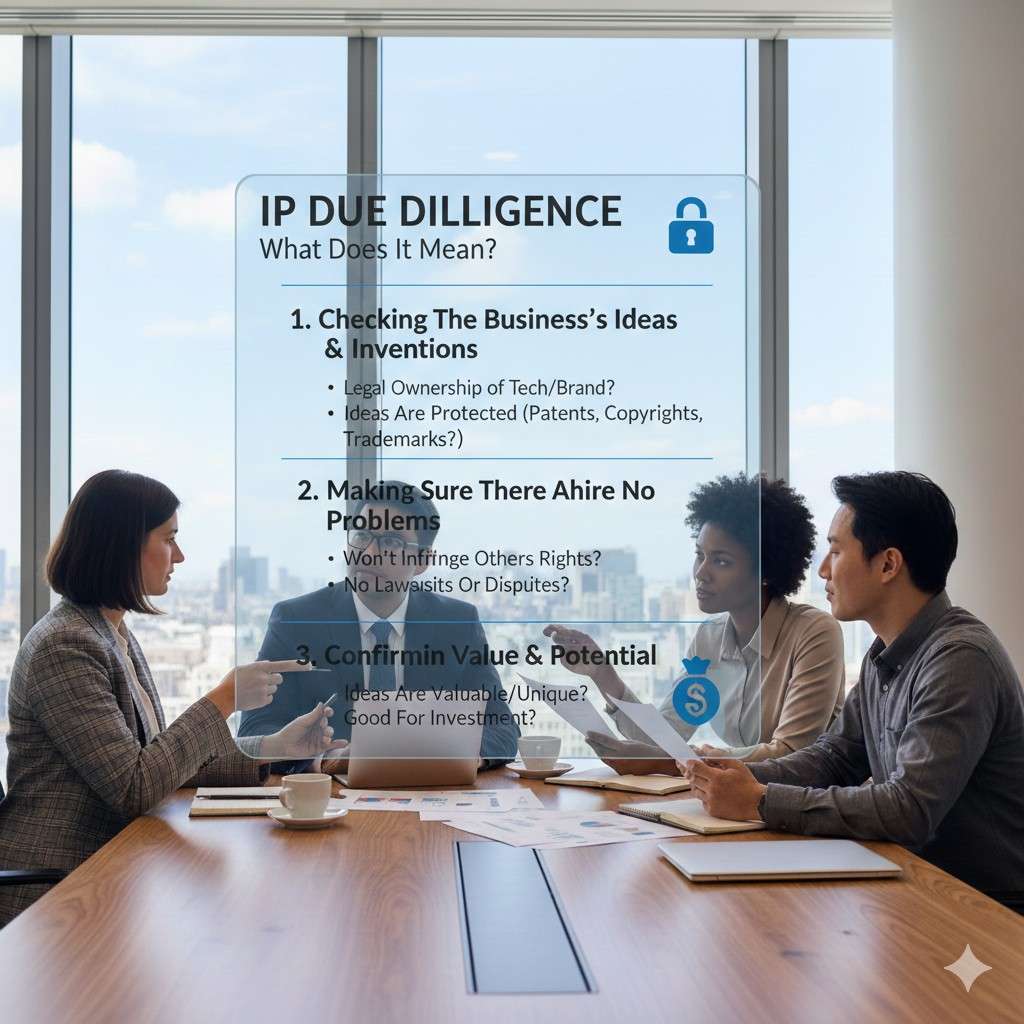

That is why IP due diligence exists. It is the part of fundraising where investors ask: “What do you actually control? Can you defend it? And is there any hidden risk that can blow this deal up later?”

This article breaks down exactly what VCs will ask for, why they ask it, and how to prepare without panic. If you want help doing this the right way—especially if you are building in AI, robotics, or deep tech—you can apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

What “IP due diligence” really means (in plain words)

IP due diligence is a structured check on your intellectual property. Investors want to confirm four things:

- Ownership: your company truly owns what it claims

- Protection: your advantage is protected, or at least protectable

- Freedom to operate: you are not likely to get sued the moment you scale

- Cleanliness: there are no messy gaps like missing assignments, open-source issues, or contractor claims

The key point most founders miss is this: investors are not asking these questions because they distrust you. They ask because they have been burned before. A single unsigned invention assignment, a single “friend helped us build it” situation, or a single dataset you do not have rights to can kill a round late in the process. And late-stage deal deaths are brutal. They waste months and distract the team.

So the goal is not to “sound impressive.” The goal is to be clean, clear, and provable.

And yes, even at pre-seed and seed, investors are asking more questions now than they used to. AI made copying cheaper. Robotics made defensibility more important. And many funds have learned that “we’ll file later” often turns into “we never filed.”

If you’re early and want to set this up right from day one, Tran.vc helps technical founders build IP foundations using up to $50,000 of in-kind patent and IP services, so you can raise with more control and less stress. Apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

The first question VCs are really asking (even if they don’t say it)

Here is the hidden question behind almost every IP diligence request:

“If this company becomes big, can they keep their advantage long enough to win?”

They will test this in practical ways:

- Can another team rebuild this in 6 months?

- Can a big company ship a similar thing and crush you on distribution?

- Is your edge a trade secret you can actually keep secret?

- Do you have patents that block others, or at least protect key parts?

- Are you building on tools, data, or code you do not control?

The good news: you do not need a massive patent portfolio to answer this well. What you need is a tight story plus solid paperwork.

A lot of founders fear diligence because they think it is a legal exam. It is not. It is more like a trust exam. Investors want to see that you run your company like a real company.

What VCs will ask for: the core IP document set

When diligence starts, you will usually get a request list. It may look long. But most of it is simple if you prepare early.

1) A clear list of what you say you own

This is the “IP inventory.” It should include:

- Patents filed (even provisional)

- Patent applications in progress

- Trademarks (company name, product names)

- Copyrightable assets (key codebases, core docs)

- Trade secrets (what you keep internal and how)

- Key datasets and where they came from

- Key models and how they were trained

- Key hardware designs, CAD, firmware, schematics (for robotics)

Investors are not expecting a 30-page memo. They want a clean view. They want to know what matters and what does not.

The common mistake: founders either bring nothing, or they dump a messy folder of random PDFs. Both create doubt.

A practical way to do it: keep a one-page summary that maps each major product “edge” to the IP type you use to protect it. You do not need fancy words. You just need clarity.

Example in plain language:

- “Our edge is how the robot grips soft items without damage.”

Protection: patent filings around grip mechanism + control method, and trade secret on tuning process. - “Our edge is the model that predicts failures in the field.”

Protection: patents around data pipeline + prediction method, and trade secret around feature sets + labeling process.

That kind of mapping helps investors see that you think like a builder and an owner.

If you want help building that map, Tran.vc does this with founders all the time. Apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

2) Proof the company owns the work (this is where many deals break)

This section is bigger than patents. It is about ownership of everything your company builds.

VCs will ask:

- Do all founders have signed invention assignment agreements?

- Do employees have signed invention assignment agreements?

- Did any contractors write code or design parts? If yes, do you have proper IP assignment from them?

- Did anyone do early work before the company was formed? If yes, was it assigned into the company?

- Are there any university ties (labs, grants, professors) that could claim rights?

This is not paperwork for paperwork’s sake. IP ownership problems can create lawsuits. Or worse, they can create uncertainty that scares off acquirers later.

Here is the uncomfortable truth: “We made this before incorporation” is a common red flag. It is not fatal, but you must clean it up properly.

Founder IP assignments: what investors want to see

Investors want to see that each founder:

- Assigned inventions to the company

- Is under confidentiality obligations

- Has no conflicting obligations to a prior employer

- Is not using prior employer code, tools, or proprietary info

That last part matters a lot in AI and software. If a founder built a big chunk of the system while still employed somewhere else, VCs will worry the employer could claim it.

Even if that seems unlikely, investors do not like “unlikely” during diligence. They like clean.

Contractors: the silent problem

If you paid a contractor to build your first version, you need to confirm the contract clearly says:

- work made for hire (where allowed)

- assignment of all IP rights to your company

- confidentiality obligations

- no use of contractor’s pre-existing code unless licensed

A lot of founders use simple freelancer templates that do not fully assign IP. Investors will check this. If the contractor owns the code, you may not own your own product. That is not a joke. It happens.

Universities and labs: the tricky edge case

If any founder did the work at a university lab, used university equipment, or was funded under a grant, the university may have rights. Many universities claim ownership of inventions created by faculty and sometimes by students if resources were used. The exact rules vary.

VCs may ask:

- Was any work done under a sponsored research agreement?

- Are any founders faculty?

- Is any IP licensed from a university?

- Are there any obligations to share revenue or grant rights?

If you are in robotics, this comes up more often than you think.

The smartest move is to address this early and document it clearly. A clean “no university claim” memo is often enough if the facts are simple. If it is not simple, you may need a license or a written waiver.

Patents: what investors actually care about (and what they don’t)

Many founders think VCs want patents because they like “moats.” That is part of it, but the deeper reason is this:

Patents are a signal that your edge is real and that you have thought about protecting it.

But VCs do not treat patents like magic. They know patents can be narrow. They know patents take time. They know some patents are easy to design around.

So what do they ask?

They will ask what you filed, when you filed, and why

If you have filed patents, they will want:

- a list of filings (provisional, non-provisional, PCT)

- filing dates

- assignees (must be the company)

- inventors (must be correct)

- a short description of what each filing covers

If you have not filed, they will ask:

- what prevents filing now?

- what is the plan and timeline?

- what exactly would you file on first?

They also ask questions that test whether you actually understand your tech edge:

- What is truly new here?

- What part is hard to copy?

- What part is visible to the outside world?

- What part can be kept secret?

Because the best IP plan is usually a mix. Some parts should be patented because they will be visible once you ship. Other parts should be trade secrets because you can keep them internal.

Patents in AI: the question behind the question

In AI, VCs will often probe:

- Is your advantage really the model, or is it data and workflow?

- Could a competitor replicate performance with a different approach?

- What is proprietary: training data, labeling methods, feature extraction, evaluation setup, deployment pipeline?

A lot of AI startups say “our model is the moat.” Investors are cautious about that. Models change fast. Techniques spread. What tends to last longer is a unique dataset, a unique feedback loop, or a unique deployment constraint solved in a clever way.

So when VCs ask for IP, they are often trying to see if your “secret sauce” is actually something you can protect.

This is where Tran.vc is very direct with founders. If your edge is patentable, they help you shape it into strong filings. If it is better as a trade secret, they help you structure it. If it is neither, they help you find what is protectable. Apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Freedom to operate: the part founders forget until it hurts

Even if you own your IP, investors also worry about whether someone else owns IP that blocks you.

This is called “freedom to operate” (FTO). It means: can you build and sell your product without infringing someone else’s patents?

At early stage, most VCs do not expect a full FTO opinion (those can be expensive). But they will ask questions like:

- Are you aware of any patents in this space that are risky?

- Have you done a basic patent landscape scan?

- Are there known patent-heavy players (big robotics firms, legacy industrial vendors, medical device giants)?

- Are you selling into regulated markets where incumbents patent aggressively?

They also watch how you respond. If you say “we never looked,” some will shrug. Others will worry you are walking into a wall.

A practical approach: do a targeted scan around your key technical features and main competitors. Then document the search and the reasoning in plain language. Investors like to see you took reasonable steps.

Open source: the fastest way to create surprise risk

This is a big one in software and AI. VCs may ask:

- Do you use open-source code in your product?

- Do you track licenses?

- Do you use copyleft licenses like GPL or AGPL in production?

- Do you ship anything that forces you to open-source your own code?

- Do you use open-source models, and what are their licenses?

- Do you use third-party datasets, and what are the usage rights?

Founders sometimes assume “open source is free.” It is not that simple. Many licenses are totally fine. Some have obligations that can conflict with how you sell software.

Investors do not hate open source. They hate surprises.

If you can say, calmly: “Yes, we use open source; here is how we track licenses; we avoid strong copyleft in our proprietary core; here is our review process,” you will look very mature.

Data rights: the new IP diligence battlefield

In AI, data is often more important than patents. VCs will ask:

- Where did your training data come from?

- Did you collect it, license it, scrape it, or buy it?

- Do you have written permission to use it for training and commercialization?

- If customers provide data, what does your contract say you can do with it?

- If you label data using vendors or crowdworkers, do you own the labels?

- If you use synthetic data, do you own the generator and the rules?

This is not academic. Investors have seen deals get messy when a startup cannot prove it has rights to use key data for commercial use.

A simple rule: if you cannot explain your data rights in a few clear sentences, you are not ready for diligence.

How VCs evaluate your answers (even more than the documents)

Here is what investors are watching during IP diligence:

- Do you answer directly or dodge?

- Do you have basic organization?

- Do you understand where your risk is?

- Do you have a plan to fix gaps quickly?

- Do your documents match your story?

They do not need perfection. They need confidence.

A founder who says: “We found two gaps, here is our plan and timeline to fix them,” often looks better than a founder who pretends there are no gaps.

A simple way to prepare before you raise (without turning into a lawyer)

If you want to make this easy on yourself, treat diligence like a folder you build slowly.

At a minimum, have:

- signed founder assignments

- signed employee/contractor assignments

- a simple IP inventory (one page is fine)

- a record of patent filings (if any)

- a basic open-source license tracking approach

- a clear data rights story

- a short description of trade secrets and how you protect them

When you have these, diligence becomes a smooth step instead of a fire drill.

This is exactly the kind of foundation Tran.vc helps founders build early—so you can raise with leverage, not desperation. Apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

What VCs will ask in meetings (and why the wording matters)

The “what do you own” question

In live calls, most investors won’t start by asking for a document list. They will start with something that sounds simple, like: “What’s defensible here?” or “What’s hard to copy?”

They are testing whether you can explain your edge without hiding behind buzzwords. If your answer is clear, they assume you understand your business. If your answer is vague, they assume you are early or exposed.

A strong answer connects your edge to a real mechanism. You explain what makes it work, and why others cannot do the same quickly. You keep it grounded in what you built, not what you hope.

The “what’s patented” follow-up

If they hear anything that sounds protectable, they will ask about patents next. They are not hunting for a huge portfolio. They want to know whether you filed on the right ideas early, and whether the company is set up to file more as you learn.

If you have filed, they will look for a simple description of what each filing covers. If you have not filed, they want to hear a plan that matches your roadmap and your budget.

You do not need to overshare technical details in the meeting. You need to show you know what matters, and that you are not asleep at the wheel.

The “who invented this” test

This one comes up in different forms. “Who built the first version?” “Was any of this done before the company existed?” “Did you hire contractors?”

They ask because ownership problems are common, and because they can be expensive to fix later. They also ask because the answer reveals how you operate as a founder.

If you say “a friend helped” or “a contractor built most of it,” expect deeper questions. The goal is not to look perfect. The goal is to show you have signed assignments and clean rights.

Ownership and assignment (the paperwork that stops deals from breaking)

Founder IP assignment and invention agreements

Investors expect that every founder has signed papers that assign inventions to the company. They also expect confidentiality obligations and clear terms that cover both past and future work.

If you did early work before the company was formed, you want that work assigned into the company as well. Otherwise, you are asking an investor to fund an entity that may not own the core asset.

This is one of those topics where “we will do it later” sounds risky. The fix can be simple, but it must be done correctly and consistently.

Employee agreements that match reality

If you have employees, the company should have signed agreements that cover confidentiality and invention assignment. Investors may also look for clarity around employment status, role, and the date they joined.

The reason is not bureaucracy. If an employee later leaves and claims they own part of the invention, the dispute gets messy fast.

When documents are missing or inconsistent, investors worry that other basics may also be loose. Clean agreements remove that doubt.