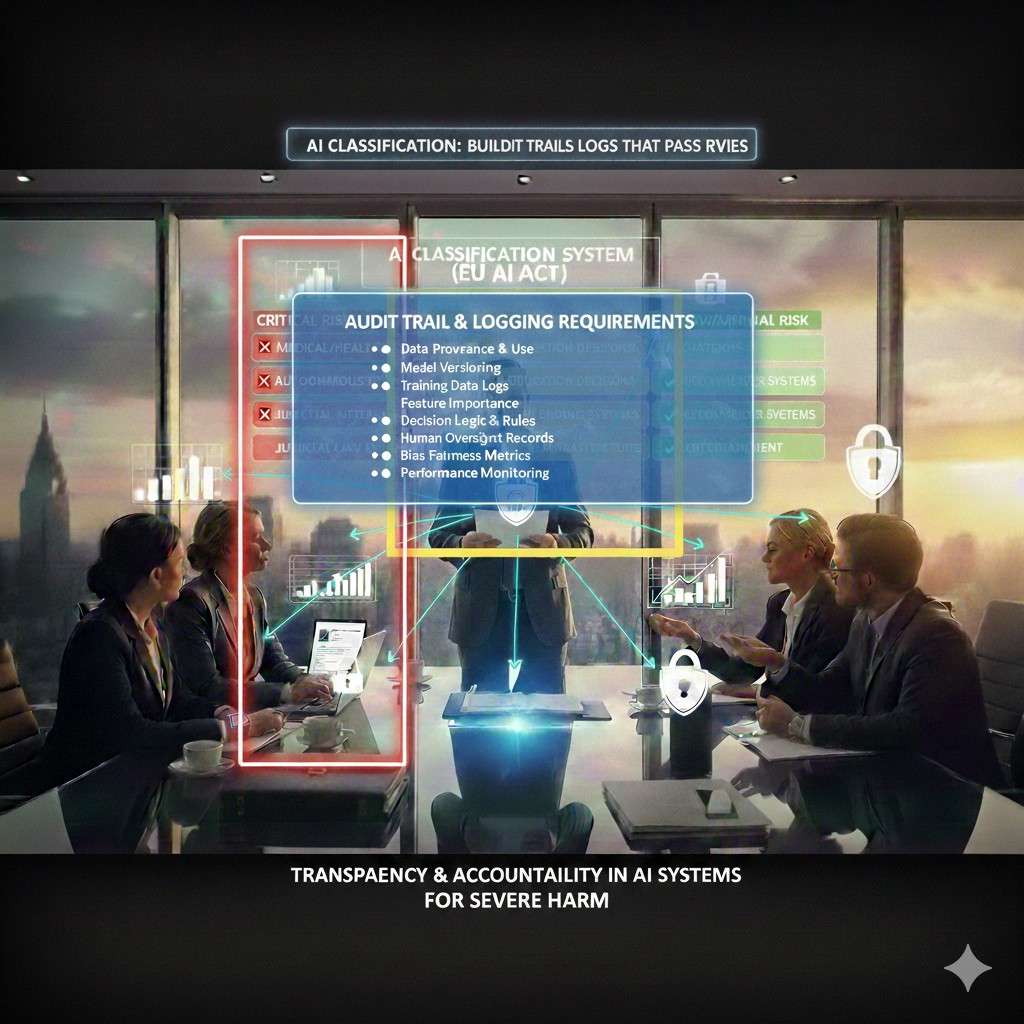

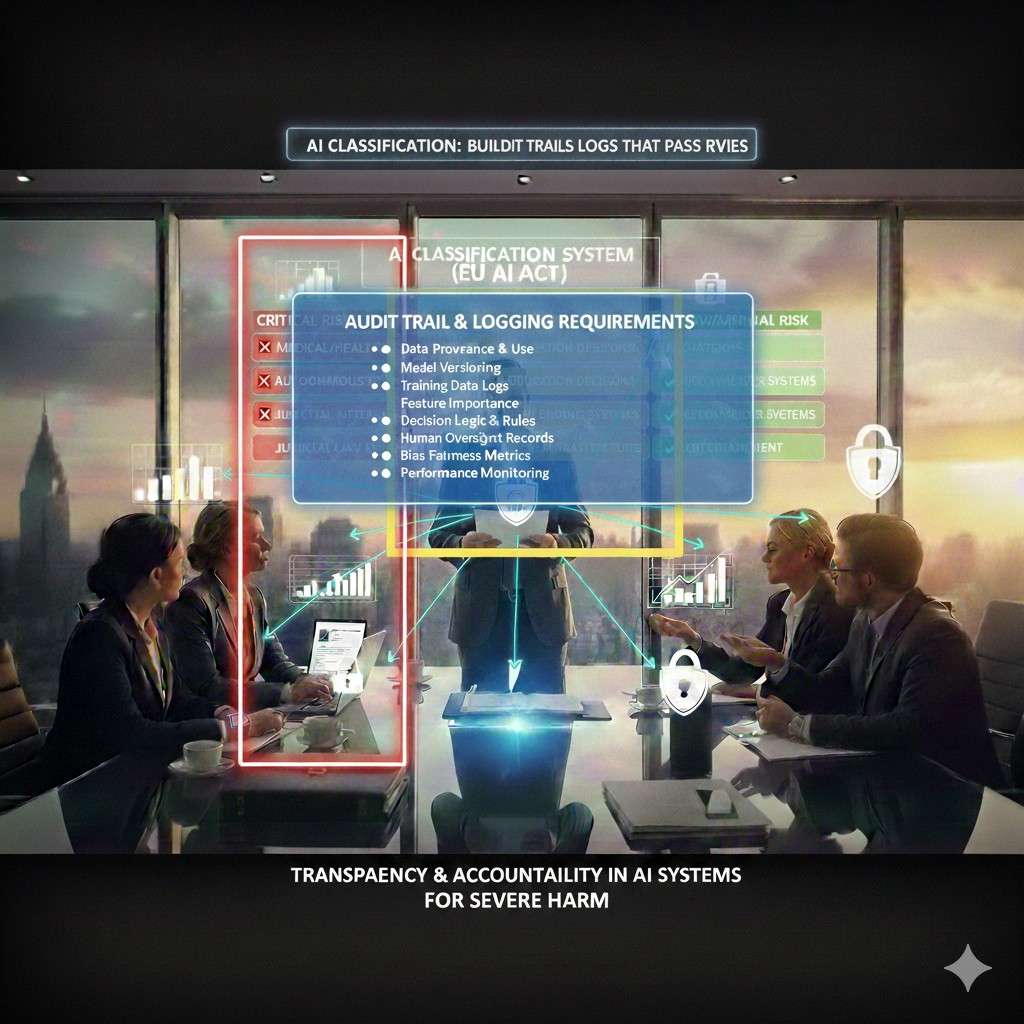

Audit trails and model logs sound like paperwork. But when a customer, partner, regulator, or investor asks, “Can you prove what your system did, when it did it, and why?”—your answer cannot be a guess.

If you build AI or robotics, your product makes choices in the real world. That makes trust part of the product. A strong audit trail is how you earn that trust. It is also how you pass security reviews, vendor checks, and due diligence without losing weeks in back-and-forth.

This article will show you how to build audit trails and model logs that hold up under review. Not in theory. In a way a real reviewer will accept. And in a way your team can keep running as you ship fast.

If you are building something defensible and fundable, this also ties straight into IP. The way you design logging, traceability, and model governance often reflects the “how” of your system—your unique approach. If you want help turning that into protectable assets, you can apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/.

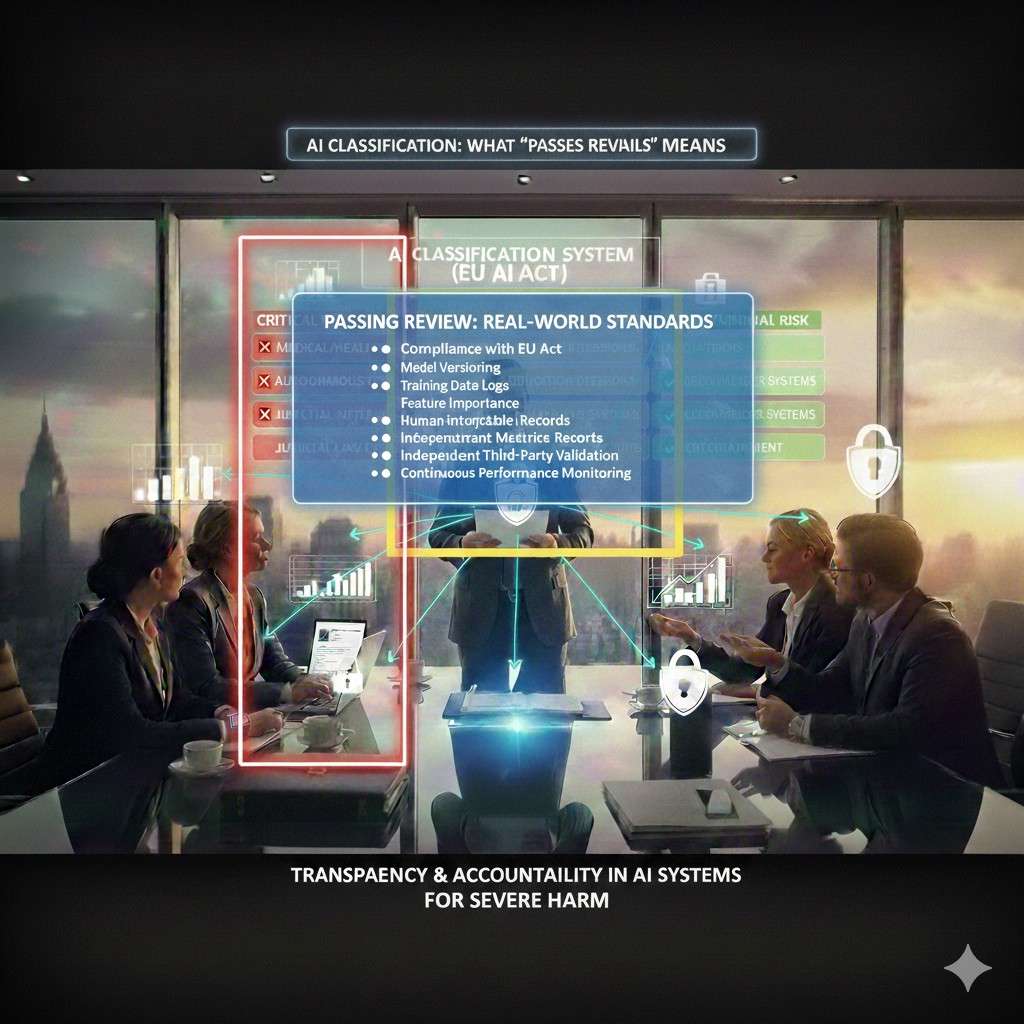

What “passes review” really means

Most founders think a review is a checklist. It is not. It is a person with limited time trying to answer three questions:

- Can we trust your outputs?

- If something goes wrong, can you explain it?

- Can you show proof, not stories?

So when we say “passes review,” we mean your logs and audit trail do four things well:

They are complete enough to replay key events.

They are hard to fake or change after the fact.

They are easy to search and summarize.

They protect privacy and secrets.

Reviewers do not want to read a million lines of logs. They want clear evidence. The trick is building logs that are detailed under the hood, but easy to present on the surface.

Start with the outcome you need: a clean “story of an event”

Every review boils down to one thing: “Show me what happened.”

So your system should be able to produce an event story like this:

- A user (or robot) did something.

- The system received an input.

- A model version ran.

- It used certain settings.

- It produced an output.

- A human approved or rejected it (if that applies).

- The system acted on it.

- You can point to the exact data and code versions tied to that decision.

That is the goal. Everything else is structure.

A mistake teams make is logging “stuff” without a plan. You end up with noisy logs that still do not answer the key questions. Instead, you want to log around decisions.

Any time the system makes a choice that matters—log it in a way you can defend.

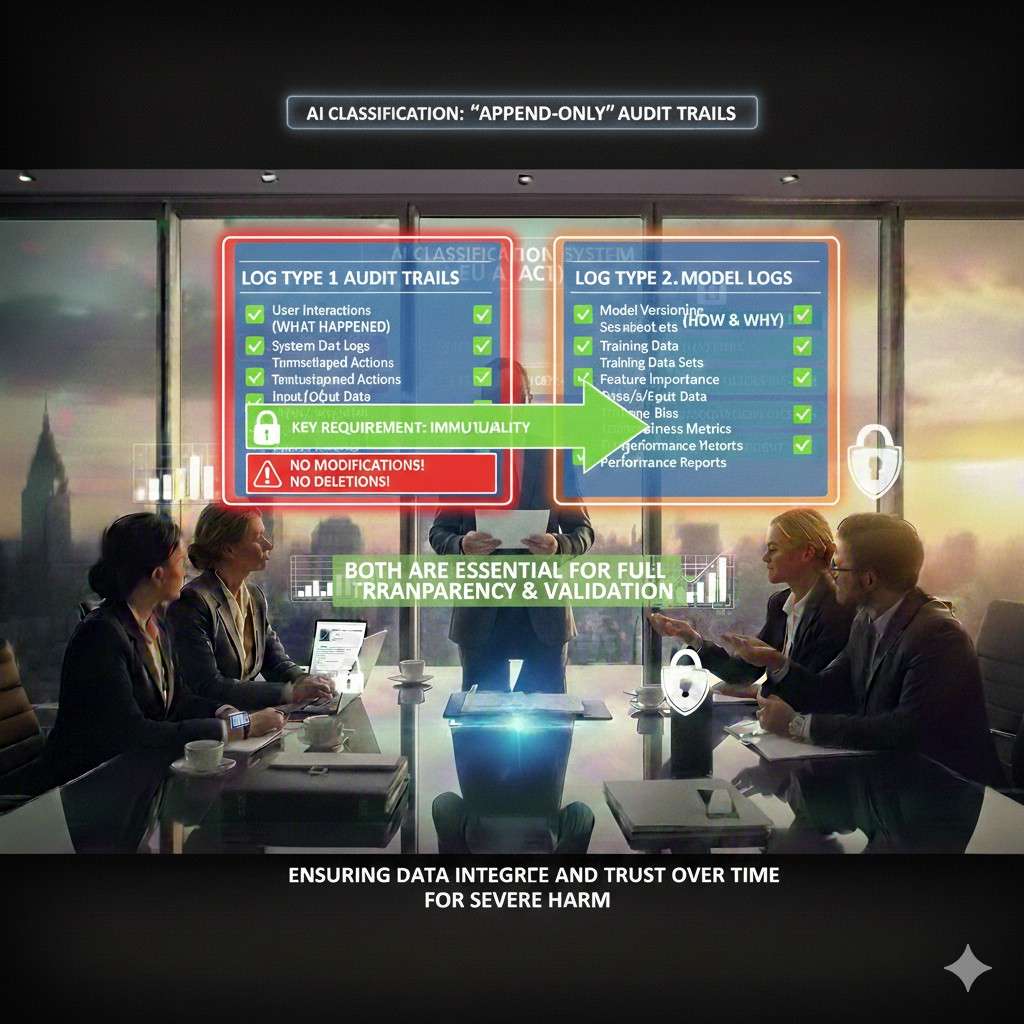

Two log types you need, and why both matter

Think of it like a plane.

There is a flight log, and there is a black box.

In AI products, you need:

1) Audit trail (the “flight log”)

This is the who, what, when. It is about actions and access.

Examples:

A user changed a setting.

A dataset was updated.

A model was promoted to production.

A robot was put into manual mode.

A batch job ran and wrote results.

2) Model logs (the “black box”)

This is what the model saw and did.

Examples:

Which model version ran.

The exact prompt or feature set (with safe redaction).

The config values.

The confidence score.

The post-processing rules used.

The fallback path taken when the model was unsure.

A reviewer will look for both. The audit trail shows control. The model logs show behavior.

If you only have one, you will fail the “prove it” test.

The fastest way to design your logging: pick your “review moments”

Instead of starting from tools, start from moments when someone will ask for proof.

Here are common review moments in robotics, AI, and deep tech:

A customer’s security team asks how you track admin actions.

A large enterprise asks how you investigate incidents.

A hospital asks how you handle patient data exposure.

A factory asks how you prevent unsafe robot behavior.

An investor asks how you manage model drift and updates.

A regulator asks how a decision was made.

For each moment, write down what evidence you would want if you were on the other side.

Then build logs that produce that evidence with low effort.

This mindset saves months.

Your audit trail must be “append-only” in practice

A log that can be edited is not a log. It is a note.

When reviewers say “audit trail,” they expect that events are not quietly changed. They expect tamper resistance.

You do not need to overbuild this on day one, but you do need a clear stance:

- Logs should be written once.

- Changes should be recorded as new events, not edits.

- Deletion should be rare and controlled, and itself logged.

In simple terms: the trail should only move forward.

How do you get there?

A practical approach many startups use:

Store audit events in a central system.

Restrict write access to the logging service.

Restrict delete access to almost nobody.

Set retention rules that match your product risk.

Export immutable copies to cheaper storage for long-term hold.

Even if your first version is not perfect, a reviewer wants to see intent and controls.

Define one “event format” your whole company uses

This is boring work that pays back forever.

If every team logs in a different shape, you cannot answer questions fast. Reviewers will feel that chaos.

Pick one format and stick to it.

At minimum, each event should carry:

A timestamp in a clear standard.

A unique event ID.

A request ID or trace ID.

The actor (user, service, robot, API key).

The action (what happened).

The target (what it happened to).

The outcome (success, failure, blocked).

The environment (prod, staging, dev).

The model version (if a model was involved).

A “why” field when there is a rule-based reason.

You can keep this simple and still strong.

The most important part is the request/trace ID. It lets you stitch together a full story across services.

If you do only one thing from this article, do that.

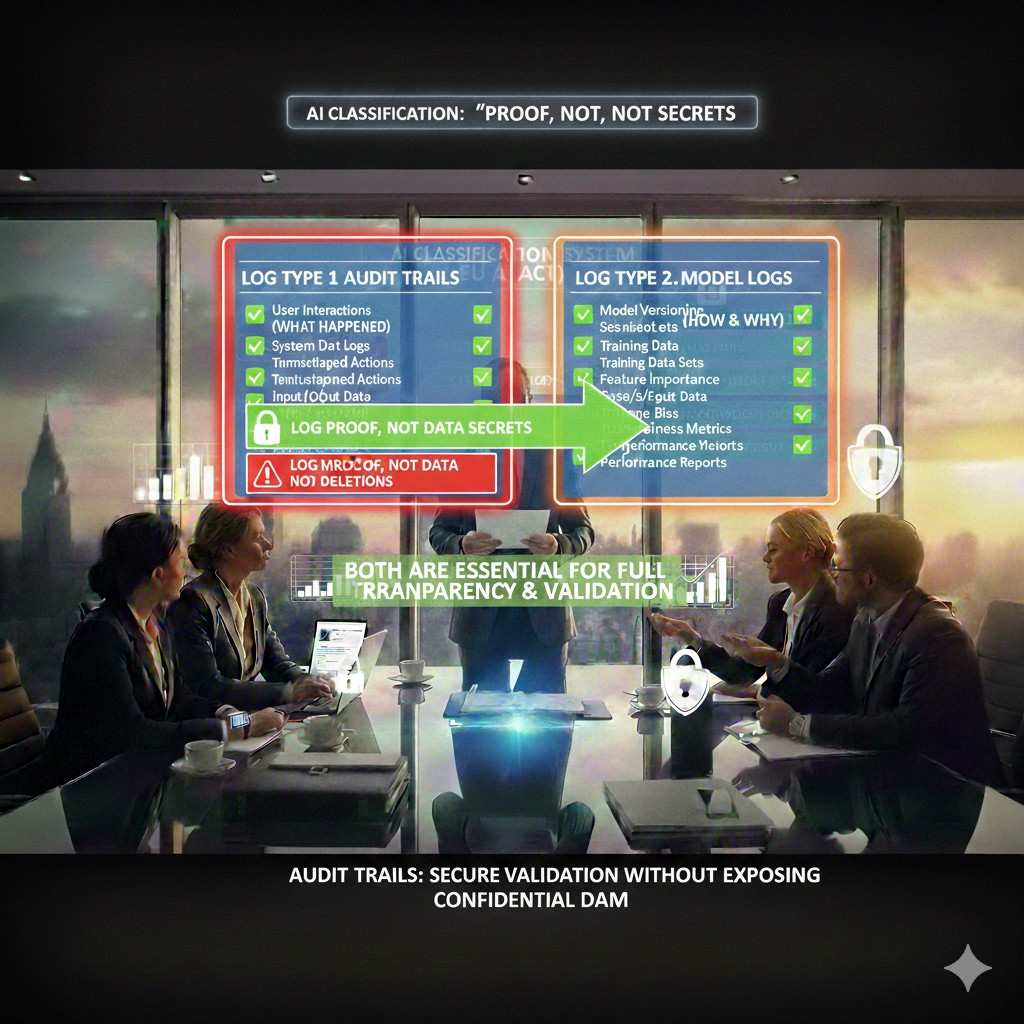

Do not log secrets, but do log proof

Teams often panic here: “If we log inputs, we will leak data.” That fear leads to no logging. Then you cannot debug, cannot prove, cannot pass reviews.

The middle path is this:

Log enough to prove what happened, while masking what should not be stored.

A reviewer usually accepts these patterns:

Store hashes of sensitive fields so you can match later without storing the raw value.

Store short excerpts instead of full payloads.

Store references (pointers) to encrypted blobs with strict access.

Store tokens that can be rehydrated only in a controlled process.

For example, if you run a model on an image, you might log:

The image ID, not the image.

The hash of the image file.

The model version and config.

The output label and score.

Then, in a secure system, you can access the image later if needed, with approvals.

This proves integrity without oversharing.

Model logs that pass review: what a reviewer will ask for

Model logs are tricky because they can explode in size, and because they can include sensitive data.

Still, reviewers will ask:

Which model version produced this output?

What data or prompt went in?

What settings were used?

Was there a human in the loop?

Did the system override the model output?

What safeguards ran?

How do you catch drift?

So your model logging plan should cover:

Model identity: name, version, commit hash, build ID.

Runtime config: temperature, max tokens, thresholds, safety filters, feature flags.

Input fingerprint: not always raw input, but enough to tie output to input.

Output record: prediction, score, and any structured explanation you produce.

Decision path: what rules or gates changed the output.

Fallback behavior: what happens if the model fails or is unsure.

Latency and errors: timeouts, retries, partial failures.

That is what makes a log defensible.

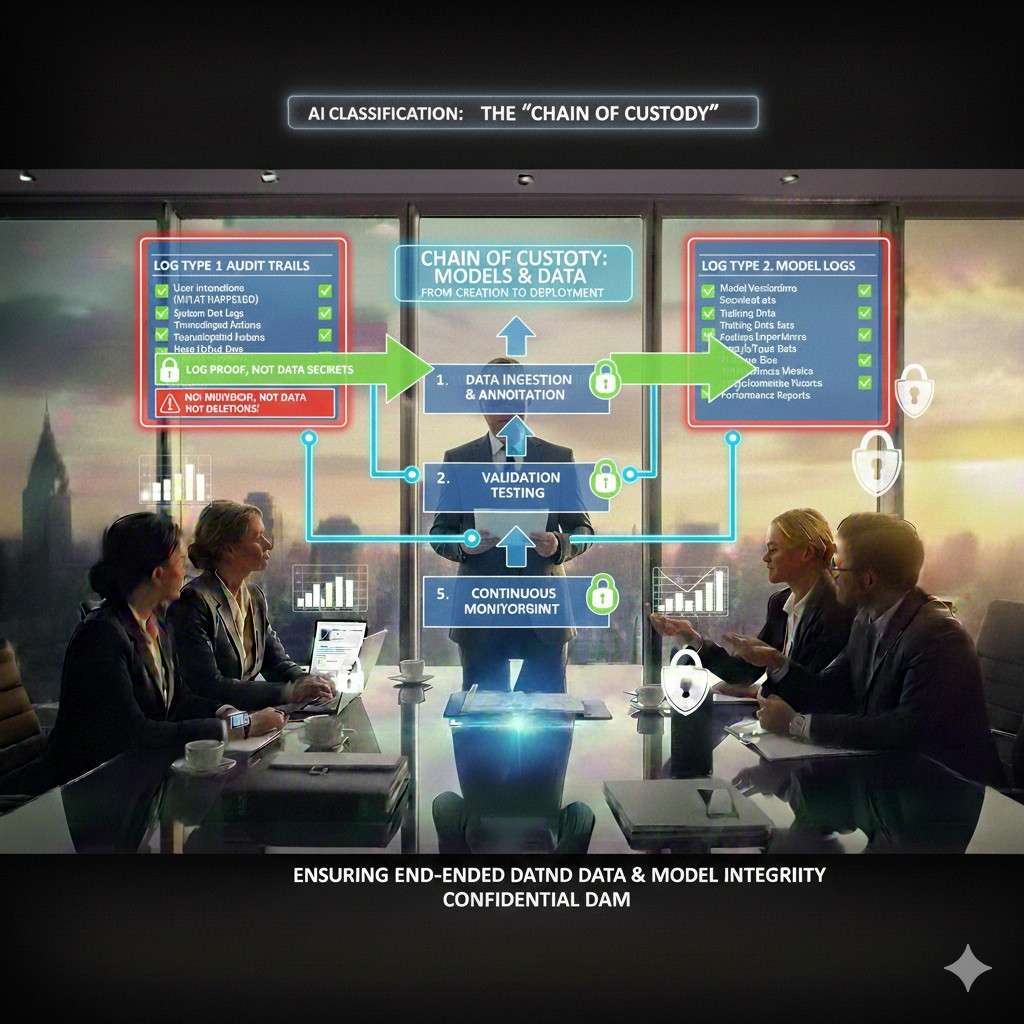

The “chain of custody” for models and data

If you ship models, you must show control over how they are built and deployed.

A clean chain of custody is simple:

You can show where training data came from.

You can show how it was cleaned.

You can show which code trained the model.

You can show who approved the model.

You can show what tests it passed.

You can show when it went live.

You can show what changed since last time.

This does not require a huge platform. It requires discipline.

A good first step is to treat models like releases:

Every production model has a version.

Every version has an owner.

Every version has a short “release note.”

Every version has a link to training run metadata.

Every version has an evaluation snapshot.

Every promotion to production creates an audit event.

This one habit makes reviews much smoother.

The hidden trap: logs that nobody can use

Some teams log everything, then still fail review. Why? Because they cannot answer questions quickly.

A reviewer will ask something like:

“Show me all admin actions in the last 30 days.”

“Show me what model version handled this customer incident.”

“Show me why the robot stopped at 10:14am.”

If your answer is “we need to write a script,” you look unready.

So build “review queries” early.

That means you should be able to run simple filters like:

By customer tenant.

By actor.

By action type.

By model version.

By time window.

By outcome.

Even if you are small, make sure your log store and schema support that.

This is not about fancy dashboards. It is about being able to respond fast with proof.

Make logs useful for your team first

Here is a simple truth: if logs help your engineers daily, they will stay healthy. If logs exist only for compliance, they will rot.

So make logs solve your own pain:

Debugging issues.

Replaying incidents.

Understanding model failures.

Tracking feature rollouts.

Reducing support time.

When logging is tied to speed, it gets love. And then it also passes review.

Where Tran.vc fits into this

Audit trails and model logs are not only “security work.” They can be part of your moat.

If you have a unique way to trace decisions, validate models, or ensure safe robotic actions, that “how” can become protectable IP. It can also make enterprise deals easier because you look mature early.

Tran.vc helps technical founders build that kind of leverage from day one, and we invest up to $50,000 in-kind in patent and IP services to do it. You can apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/.

Building Audit Trails and Model Logs That Pass Review

Why this matters more than most teams think

Most teams treat logging like a side task. Something you “add later” after the product works. But reviews do not wait for later. They show up the moment a serious buyer cares, or the moment an incident happens.

A good audit trail is not only for compliance. It is a way to prove you are in control. It tells a clear story about what your system did, who touched it, and what changed over time. When a reviewer senses you can answer questions fast, they relax.

Model logs are different. They explain how your AI behaved in real time. They show which model ran, what inputs it saw, what settings were used, and what the system did with the output. Together, audit trails and model logs turn “trust us” into “here is the proof.”

What “passing review” looks like in real life

A review is rarely a single test. It is a set of questions from security, legal, engineering, and sometimes operations. They may ask for documents, but they will also ask for live evidence. They want to see that your logs are complete, protected, and useful.

Passing review means you can trace a decision from start to finish. It also means you can show that logs cannot be quietly changed. You do not need perfection, but you do need a structure that is consistent and repeatable.

The kind of proof reviewers accept

Reviewers do not want raw noise. They want traceable facts. They want timestamps, IDs, and a clear link between a user action and what the system did next. They also want to see that sensitive data is handled with care.

If you can produce a clean event story within minutes, you are ahead of most early-stage teams. That speed is not a luxury. It is often what closes a deal.

Part 1: Build the Audit Trail First

What the audit trail is actually for

An audit trail is your system’s record of actions and access. It answers “who did what, and when.” It also shows outcomes like success, failure, or blocked actions. This is the trail you use when a customer asks about admin controls or when you investigate a security issue.

In robotics, the audit trail should also cover operational events. For example, a mode change, a safety stop, a calibration change, or a shift from autonomous to manual. These are not “nice to have” events. They are often the most important ones.

Define “audit events” as decisions that matter

Audit trails get messy when you log everything. The better approach is to log decisions that matter. If an action could change a result, affect safety, expose data, or change system behavior, it belongs in the audit trail.

A simple way to decide is to ask: if this action caused harm or a serious bug, would we need proof of what happened? If the answer is yes, it must be an audit event. If not, it can be a normal debug log.

The minimum fields every audit event needs

You need a consistent format so events can be searched, grouped, and replayed. Reviewers often look for structure because structure shows maturity. At minimum, every audit event should include time, actor, action, target, and outcome.

It should also include a trace or request ID so you can connect events across systems. This is how you turn scattered logs into a single storyline. Without that connection, you will spend hours stitching things together during an incident.

Make it “append-only” so it holds up under scrutiny

Audit trails lose value when people can edit or delete them quietly. Reviewers know this, and they will often ask what prevents tampering. You do not need a perfect system, but you do need controls that show intent.

A practical standard is: do not update events in place. If something changes, write a new event. If something must be removed for legal reasons, log that removal as its own event and keep the reason clear. This keeps the trail honest and easier to defend.

Access control for logs is part of the audit trail

Many teams forget that logs themselves are sensitive. If anyone can read production logs, you may be leaking customer data. If anyone can delete logs, you have no trail. So your logging platform should have clear roles.

A reviewer will want to know who can view, export, and delete logs. If you can answer that cleanly and show it is enforced, you gain trust quickly. If you cannot, the rest of your story becomes harder.

Part 2: Make Model Logs That Explain Behavior

What model logs are meant to prove

Model logs exist to explain why your AI produced an output. They connect model identity, runtime settings, inputs, and outputs in one record. When a customer questions a result, you need to show more than “the model said so.”

Good model logs let you answer questions like: which model version made this call, what thresholds were applied, what guardrails ran, and whether a fallback path triggered. This is the difference between “we hope it’s correct” and “we can show how it happened.”

Separate “model output” from “system decision”

A key distinction reviewers care about is the difference between what the model predicted and what the product decided to do. In many products, the model output is only one signal. A rules layer may override it. A human may approve it. A safety system may block it.

Your logs should reflect that clearly. Store the raw model output and store the final action the system took. Also store the reason for any override. This helps you prove that you use guardrails, not blind automation.

Model identity must be unambiguous

Saying “we used version 3” is not enough. You want a model identity that cannot be confused. That usually includes a model name, a version tag, and a build or commit reference. If you deploy with containers, the image digest can also help.

In a review, ambiguity looks like risk. Clarity looks like control. When you can point to an exact artifact, reviewers stop worrying that your team is swapping models without tracking.

Log runtime settings that change outputs

Many failures are not from the model itself, but from settings around it. Thresholds, temperature, max tokens, sampling rules, safety filters, post-processing, and feature flags can all change results. If you do not log these, you cannot explain behavior later.

This is especially true for LLM products where small prompt and parameter changes can swing outputs. A reviewer will not accept “it depends.” They will want to know what settings were used at the time of the event.

Log inputs safely without storing what you should not store

Input logging is where teams often freeze. They fear leaking personal data, customer secrets, or regulated data. That fear is valid, but it should not lead to zero traceability. You need a safe way to log the fact of an input without always logging the raw input.

Common safe patterns include hashing sensitive fields so you can match later, storing short excerpts, or storing a pointer to an encrypted blob with strict access. The goal is to make later investigation possible without turning your logs into a data leak.

Part 3: Design Logs Around a “Trace Story”

The trace story is the unit of trust

Reviewers do not review logs line by line. They review stories. They want to pick a single transaction and trace it end to end. This is why trace IDs matter so much. They are the spine that holds the story together.

A trace story usually begins at an API call, a device event, or a job run. It then flows through services, model calls, decision layers, and actions. If you can reconstruct that chain, you can handle almost any review question.

One request ID is not enough without propagation

Teams often generate a request ID at the edge, then lose it inside background tasks or async flows. That breaks the story. You need a clear rule: trace IDs must be passed through every service and queued job, and every log line must include it.

For robotics, propagation also includes device-to-cloud flows. If a robot event triggers a cloud model call, you want one connected ID that ties the device event to the model run and to the action decision. Without that, investigations become guesswork.

Build a “decision record” for high-impact actions

Some actions are more sensitive than others. A robot moving in a shared space, an AI approving a payment, a model flagging a user, or a system sending a legal notice are high-impact actions. For these, you should store a richer decision record.

A decision record is a structured log entry that captures the key context. It includes the actor, input fingerprint, model identity, model output, policy checks, override reasons, and the final action. This is the record that often gets shown to reviewers.

Keep a clean difference between debug logs and audit logs

Debug logs are for engineers. Audit logs are for proof. If you mix them, you either end up with audit logs that are noisy, or debug logs that are restricted and hard to use. Both outcomes hurt you.

So define two streams. Keep audit events structured and stable. Keep debug logs flexible and high-volume. Make sure both share the trace ID so you can move from proof to deeper investigation when needed.

Part 4: Logging in Each Layer of the Stack

API and identity layer: prove who did what

At the edge of your system, log authentication and authorization clearly. You want to capture who the actor is, what role they have, what tenant they belong to, and what action they attempted. Also record whether the action was allowed or blocked.

If you use API keys, log key usage without exposing the full key. Store a key ID, not the secret. For SSO, log the identity provider and session details in a safe way. Reviewers care about this because identity is the start of every story.

Data layer: track changes, not just reads

A lot of risk comes from data changes. If a dataset is edited, a label set is updated, or a training set is swapped, you need a record. This matters for model governance and also for customer trust. Reviewers will ask how you prevent silent changes.

You should log data writes and schema changes as audit events. Also log access patterns when data is sensitive. The aim is to show you can detect misuse and understand what changed between model runs.

Model serving layer: capture the run, not just the result

When a model runs in production, you want to log more than the output. Capture the model identity, runtime settings, input fingerprint, output, and timing. Also log errors and retries because they often explain odd behavior.

For LLM tools, also log the tool calls and retrieval sources used, if your system uses them. Reviewers care because tool calls can expose data or cause actions. You want proof that tool use is controlled and traceable.

Robotics and edge layer: log state changes and safety events

In robotics, your device events are part of your audit story. Log state transitions like idle to active, manual to autonomous, safe-stop triggers, sensor fault events, and operator overrides. These events often matter more than the model logs.Building Audit Trails and Model Logs That Pass Review

Why this matters more than most teams think

Most teams treat logging like a side task. Something you “add later” after the product works. But reviews do not wait for later. They show up the moment a serious buyer cares, or the moment an incident happens.

A good audit trail is not only for compliance. It is a way to prove you are in control. It tells a clear story about what your system did, who touched it, and what changed over time. When a reviewer senses you can answer questions fast, they relax.

Model logs are different. They explain how your AI behaved in real time. They show which model ran, what inputs it saw, what settings were used, and what the system did with the output. Together, audit trails and model logs turn “trust us” into “here is the proof.”

What “passing review” looks like in real life

A review is rarely a single test. It is a set of questions from security, legal, engineering, and sometimes operations. They may ask for documents, but they will also ask for live evidence. They want to see that your logs are complete, protected, and useful.

Passing review means you can trace a decision from start to finish. It also means you can show that logs cannot be quietly changed. You do not need perfection, but you do need a structure that is consistent and repeatable.

The kind of proof reviewers accept

Reviewers do not want raw noise. They want traceable facts. They want timestamps, IDs, and a clear link between a user action and what the system did next. They also want to see that sensitive data is handled with care.

If you can produce a clean event story within minutes, you are ahead of most early-stage teams. That speed is not a luxury. It is often what closes a deal.

Part 1: Build the Audit Trail First

What the audit trail is actually for

An audit trail is your system’s record of actions and access. It answers “who did what, and when.” It also shows outcomes like success, failure, or blocked actions. This is the trail you use when a customer asks about admin controls or when you investigate a security issue.

In robotics, the audit trail should also cover operational events. For example, a mode change, a safety stop, a calibration change, or a shift from autonomous to manual. These are not “nice to have” events. They are often the most important ones.

Define “audit events” as decisions that matter

Audit trails get messy when you log everything. The better approach is to log decisions that matter. If an action could change a result, affect safety, expose data, or change system behavior, it belongs in the audit trail.

A simple way to decide is to ask: if this action caused harm or a serious bug, would we need proof of what happened? If the answer is yes, it must be an audit event. If not, it can be a normal debug log.

The minimum fields every audit event needs

You need a consistent format so events can be searched, grouped, and replayed. Reviewers often look for structure because structure shows maturity. At minimum, every audit event should include time, actor, action, target, and outcome.

It should also include a trace or request ID so you can connect events across systems. This is how you turn scattered logs into a single storyline. Without that connection, you will spend hours stitching things together during an incident.

Make it “append-only” so it holds up under scrutiny

Audit trails lose value when people can edit or delete them quietly. Reviewers know this, and they will often ask what prevents tampering. You do not need a perfect system, but you do need controls that show intent.

A practical standard is: do not update events in place. If something changes, write a new event. If something must be removed for legal reasons, log that removal as its own event and keep the reason clear. This keeps the trail honest and easier to defend.

Access control for logs is part of the audit trail

Many teams forget that logs themselves are sensitive. If anyone can read production logs, you may be leaking customer data. If anyone can delete logs, you have no trail. So your logging platform should have clear roles.

A reviewer will want to know who can view, export, and delete logs. If you can answer that cleanly and show it is enforced, you gain trust quickly. If you cannot, the rest of your story becomes harder.

Part 2: Make Model Logs That Explain Behavior

What model logs are meant to prove

Model logs exist to explain why your AI produced an output. They connect model identity, runtime settings, inputs, and outputs in one record. When a customer questions a result, you need to show more than “the model said so.”

Good model logs let you answer questions like: which model version made this call, what thresholds were applied, what guardrails ran, and whether a fallback path triggered. This is the difference between “we hope it’s correct” and “we can show how it happened.”

Separate “model output” from “system decision”

A key distinction reviewers care about is the difference between what the model predicted and what the product decided to do. In many products, the model output is only one signal. A rules layer may override it. A human may approve it. A safety system may block it.

Your logs should reflect that clearly. Store the raw model output and store the final action the system took. Also store the reason for any override. This helps you prove that you use guardrails, not blind automation.

Model identity must be unambiguous

Saying “we used version 3” is not enough. You want a model identity that cannot be confused. That usually includes a model name, a version tag, and a build or commit reference. If you deploy with containers, the image digest can also help.

In a review, ambiguity looks like risk. Clarity looks like control. When you can point to an exact artifact, reviewers stop worrying that your team is swapping models without tracking.

Log runtime settings that change outputs

Many failures are not from the model itself, but from settings around it. Thresholds, temperature, max tokens, sampling rules, safety filters, post-processing, and feature flags can all change results. If you do not log these, you cannot explain behavior later.

This is especially true for LLM products where small prompt and parameter changes can swing outputs. A reviewer will not accept “it depends.” They will want to know what settings were used at the time of the event.

Log inputs safely without storing what you should not store

Input logging is where teams often freeze. They fear leaking personal data, customer secrets, or regulated data. That fear is valid, but it should not lead to zero traceability. You need a safe way to log the fact of an input without always logging the raw input.

Common safe patterns include hashing sensitive fields so you can match later, storing short excerpts, or storing a pointer to an encrypted blob with strict access. The goal is to make later investigation possible without turning your logs into a data leak.

Part 3: Design Logs Around a “Trace Story”

The trace story is the unit of trust

Reviewers do not review logs line by line. They review stories. They want to pick a single transaction and trace it end to end. This is why trace IDs matter so much. They are the spine that holds the story together.

A trace story usually begins at an API call, a device event, or a job run. It then flows through services, model calls, decision layers, and actions. If you can reconstruct that chain, you can handle almost any review question.

One request ID is not enough without propagation

Teams often generate a request ID at the edge, then lose it inside background tasks or async flows. That breaks the story. You need a clear rule: trace IDs must be passed through every service and queued job, and every log line must include it.

For robotics, propagation also includes device-to-cloud flows. If a robot event triggers a cloud model call, you want one connected ID that ties the device event to the model run and to the action decision. Without that, investigations become guesswork.

Build a “decision record” for high-impact actions

Some actions are more sensitive than others. A robot moving in a shared space, an AI approving a payment, a model flagging a user, or a system sending a legal notice are high-impact actions. For these, you should store a richer decision record.

A decision record is a structured log entry that captures the key context. It includes the actor, input fingerprint, model identity, model output, policy checks, override reasons, and the final action. This is the record that often gets shown to reviewers.

Keep a clean difference between debug logs and audit logs

Debug logs are for engineers. Audit logs are for proof. If you mix them, you either end up with audit logs that are noisy, or debug logs that are restricted and hard to use. Both outcomes hurt you.

So define two streams. Keep audit events structured and stable. Keep debug logs flexible and high-volume. Make sure both share the trace ID so you can move from proof to deeper investigation when needed.

Part 4: Logging in Each Layer of the Stack

API and identity layer: prove who did what

At the edge of your system, log authentication and authorization clearly. You want to capture who the actor is, what role they have, what tenant they belong to, and what action they attempted. Also record whether the action was allowed or blocked.

If you use API keys, log key usage without exposing the full key. Store a key ID, not the secret. For SSO, log the identity provider and session details in a safe way. Reviewers care about this because identity is the start of every story.

Data layer: track changes, not just reads

A lot of risk comes from data changes. If a dataset is edited, a label set is updated, or a training set is swapped, you need a record. This matters for model governance and also for customer trust. Reviewers will ask how you prevent silent changes.

You should log data writes and schema changes as audit events. Also log access patterns when data is sensitive. The aim is to show you can detect misuse and understand what changed between model runs.

Model serving layer: capture the run, not just the result

When a model runs in production, you want to log more than the output. Capture the model identity, runtime settings, input fingerprint, output, and timing. Also log errors and retries because they often explain odd behavior.

For LLM tools, also log the tool calls and retrieval sources used, if your system uses them. Reviewers care because tool calls can expose data or cause actions. You want proof that tool use is controlled and traceable.

Robotics and edge layer: log state changes and safety events

In robotics, your device events are part of your audit story. Log state transitions like idle to active, manual to autonomous, safe-stop triggers, sensor fault events, and operator overrides. These events often matter more than the model logs.