Connected robots are amazing. They can move goods, clean floors, help in hospitals, scan farms, and work in places humans should not. But the moment a robot connects to Wi-Fi, LTE, or the internet, it becomes a target. Not because your team is careless, but because attackers love anything that has sensors, motors, cameras, and a network link. A hacked robot is not just “a hacked computer.” It can leak private video, map a building, break a workflow, or physically damage property.

This blog series is about the minimum cybersecurity baselines for connected robots. “Minimum” does not mean weak. It means the smallest set of rules you can adopt early so you do not build a security mess that is painful to fix later.

And because Tran.vc works with robotics and AI founders who are building real systems in the real world, I’ll keep this practical. No big theory. No long checklists. Just clear, simple steps you can take in your next sprint.

Also: strong security and strong IP go together. When you build clean security patterns into your robot, you often create patentable building blocks: safe update flows, fleet trust models, secure remote access, and control policies. If you want help turning these into defensible IP, you can apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/.

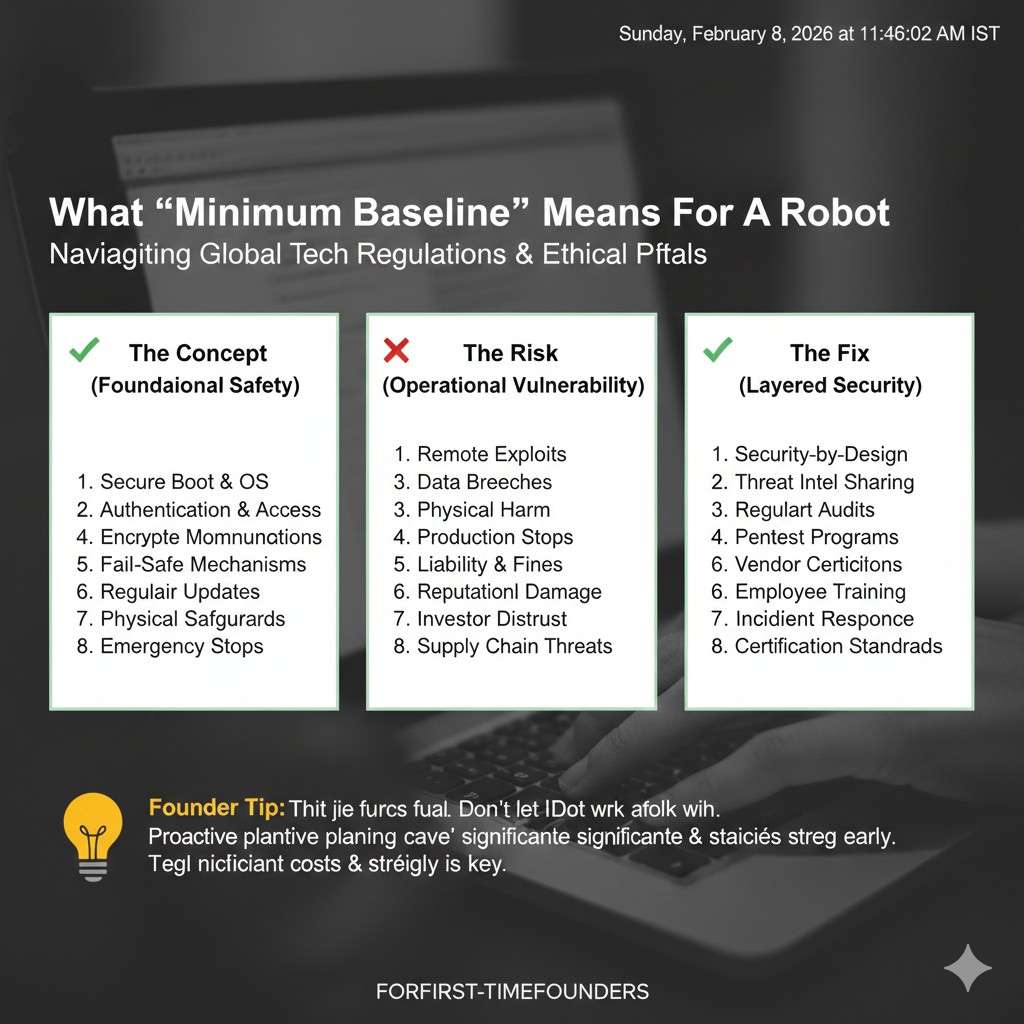

What “minimum baseline” means for a robot

A minimum baseline is the set of controls that must be true before you ship a robot to a customer site, or even to a pilot site, if it connects to anything outside your lab. You are not trying to be perfect. You are trying to avoid the most common, most costly failures.

In robotics, security failures tend to come from a few repeat patterns:

One shared password across a whole fleet.

A debug port left open because it “helped testing.”

A cloud API that trusts the robot too much.

Software updates that are easy to spoof.

Logs that contain secrets.

Remote access that turns into a permanent backdoor.

The baseline is your guardrail against these mistakes. It also helps you sell. Many customers now ask security questions in early calls. If you can answer them with calm confidence, you shorten sales cycles. You look mature. You reduce risk for the buyer.

Start with one big idea: identity first, then trust

If you remember only one thing, remember this: every robot needs its own identity, and nothing should be trusted without proof.

In simple terms, your system should know exactly which robot is talking, and your robot should know exactly which server is talking. Not “some device.” Not “a device on our Wi-Fi.” The exact robot, with its own keys, and a clear way to revoke that robot if it is lost, stolen, sold, or compromised.

A lot of teams skip this early because they are moving fast. They use a shared token in the firmware, or they hardcode a password. That works in a demo. It breaks in the field.

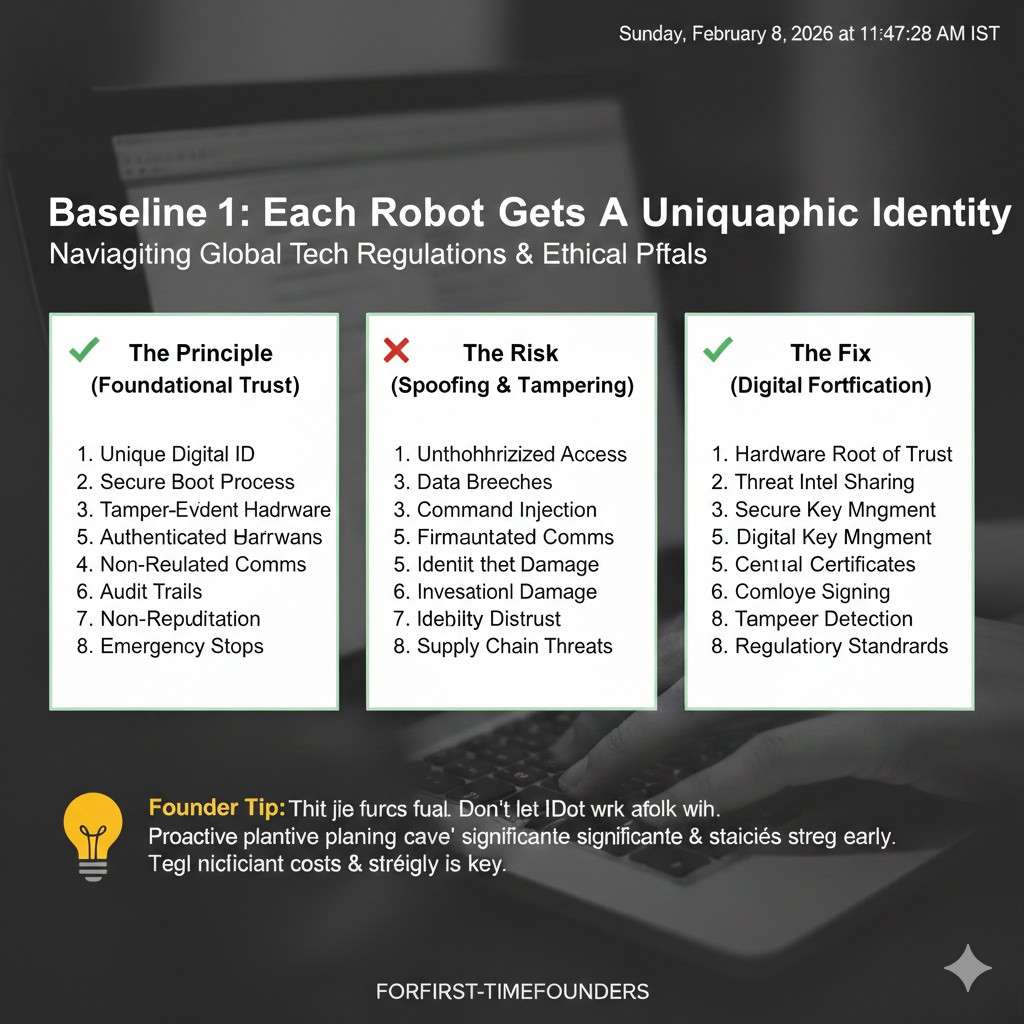

So the first baseline is unique device identity.

Baseline 1: each robot gets a unique cryptographic identity

When your robot boots for the first time, it should have a unique key pair or certificate that is not shared with any other robot. This identity should be used for mutual authentication with your cloud or control plane. That means the robot proves who it is, and the server proves who it is.

Where do the keys live? Ideally in a secure element, TPM, or similar chip. If you do not have that yet, you can still do a lot with software key storage, but you must treat it as weaker and plan to upgrade. The “minimum” here is that keys are not shared across the fleet and are not easy to read out.

A practical way to get this done without a lot of pain:

During manufacturing or provisioning, generate the robot identity.

Register it in your fleet system.

Allow the robot to connect only if it presents a valid identity.

Be able to revoke it quickly.

If you are thinking, “We don’t have manufacturing yet,” that is fine. You can do the same thing in your lab with a provisioning step. The point is to build the pattern now, so you don’t rewrite your system later.

This is also a place where you can build IP. Your provisioning flow, your trust model, and how you bind identity to hardware can be patentable if you do it in a new way. Tran.vc often helps founders spot these moments early. If you want that support, apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/.

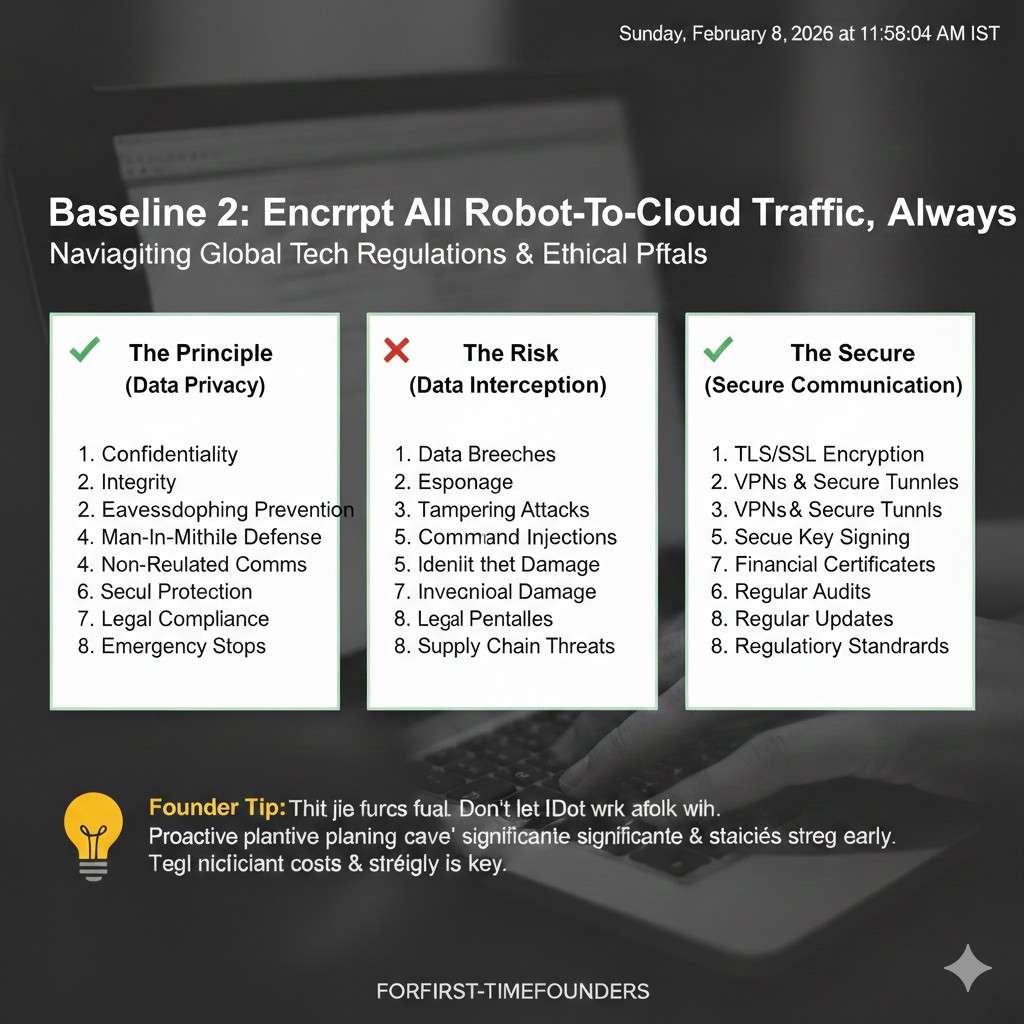

Assume the network is hostile

Robots often run in messy networks. Warehouses have dead zones. Hospitals have strict segmentation. Homes have weak routers. Factories have old gear. You cannot assume the network is safe.

So your baseline must assume an attacker can see traffic, replay messages, and try to impersonate systems.

Baseline 2: encrypt all robot-to-cloud traffic, always

This sounds obvious, but in robotics it is easy to accidentally bypass encryption for “telemetry,” or to run an internal service in plain text because it’s “only on the LAN.”

Your minimum baseline should be: all traffic that leaves the robot is encrypted in transit. That includes telemetry, commands, logs, map uploads, video streams, and update checks. Use modern TLS. Do not accept invalid certificates. Do not allow “ignore cert errors” in production builds.

A simple but strong rule: if the robot talks to your cloud, it must use mutual TLS. When mutual TLS is too heavy for a particular channel, you still encrypt and still authenticate messages strongly. No exceptions.

Baseline 3: do not expose robot services directly to the internet

Many robot stacks run things like ROS services, web dashboards, SSH, gRPC endpoints, and vendor debug tools. If any of those are reachable from the public internet, you are asking for trouble.

Your baseline should be: the robot does not accept inbound connections from the internet, unless you have a very controlled, well-designed remote access system.

Instead, use outbound connections from the robot to your control plane. Outbound is easier to secure. It works better through firewalls. It avoids “open ports” that attackers scan all day.

If your support team needs access, build it as a controlled session that is time-limited, logged, and tied to a person. Not a permanent port.

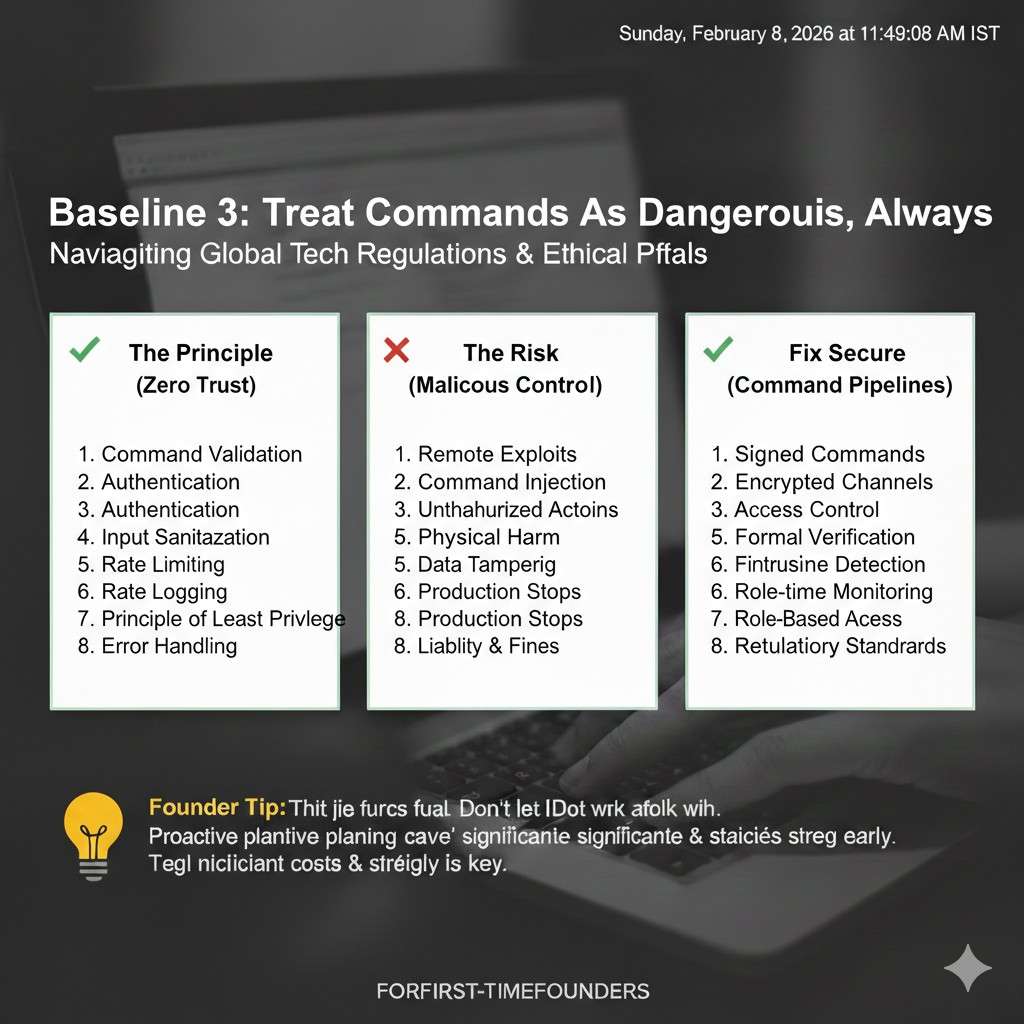

Treat commands as dangerous

A robot command is not a normal API call. “Move forward.” “Lift.” “Open.” “Stop.” These can cause real harm if misused. So commands need special care.

Baseline 4: separate telemetry from control

Telemetry is “robot status.” Control is “robot action.” Do not treat them the same.

Telemetry can be high volume and sometimes okay to buffer or delay. Control must be tight, authenticated, authorized, and rate-limited. You want clear rules about who can send control messages, from where, and under what conditions.

A practical approach:

Use one channel for telemetry and one for control.

Require stronger checks for control.

Keep control payloads small and strict.

Log every control action with the user, time, and reason.

This makes incident response much easier. If something goes wrong, you can answer, “Who told the robot to do that?” quickly.

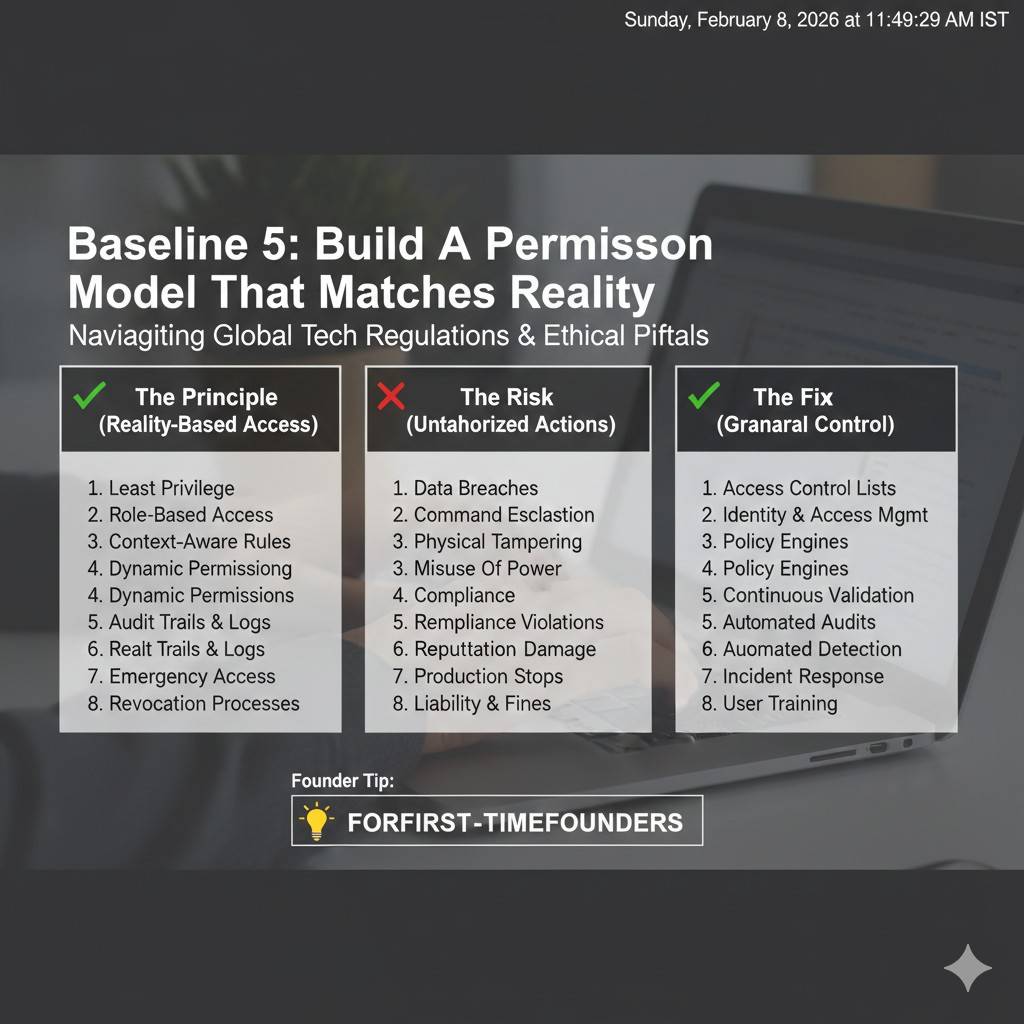

Baseline 5: build a permission model that matches reality

Many teams build a single admin login early. That is fine in week one. It becomes a problem by month six.

Your minimum baseline should support at least:

A human operator role with limited actions.

A technician role for service tasks.

An admin role for fleet settings.

You do not need a complex system. But you do need a clear boundary so a stolen operator password cannot become “full control of the fleet.”

Also, think about machine permissions. Your cloud services should not all share one master secret. Each service should have only what it needs. This limits damage when one component is compromised.

Secure updates are not optional

If your robot is connected, it will need updates. Bugs happen. Security issues are discovered. New features ship. If you cannot update safely, you will either freeze the product or you will take unsafe shortcuts.

Attackers love update systems. If they can push their own firmware, they own the robot.

Baseline 6: signed updates with rollback protection

The minimum baseline for updates is simple:

Every update must be signed.

The robot must verify the signature before installing.

The robot must refuse unsigned or tampered packages.

Then add one more: rollback protection. This prevents an attacker from forcing the robot to install an old, vulnerable version. Your robot should know the minimum allowed version, or track monotonic version numbers.

Even if you do not build a full OTA platform yet, you can still sign update files. Start now.

Baseline 7: a safe fallback path when updates fail

Robots get power loss. Networks drop. Storage fails. If an update bricks the robot, your operations team suffers. Your customer loses trust.

A minimum baseline is an A/B partition scheme or a recovery image that can boot and pull a clean update. You do not need to invent something new. Use known patterns and proven bootloaders.

This is another area where startups sometimes create unique approaches, especially for robots that have real-time constraints or multiple compute modules. If your update system has a novel design, that can become part of your IP story. Tran.vc helps founders turn those designs into patent assets. Apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/.

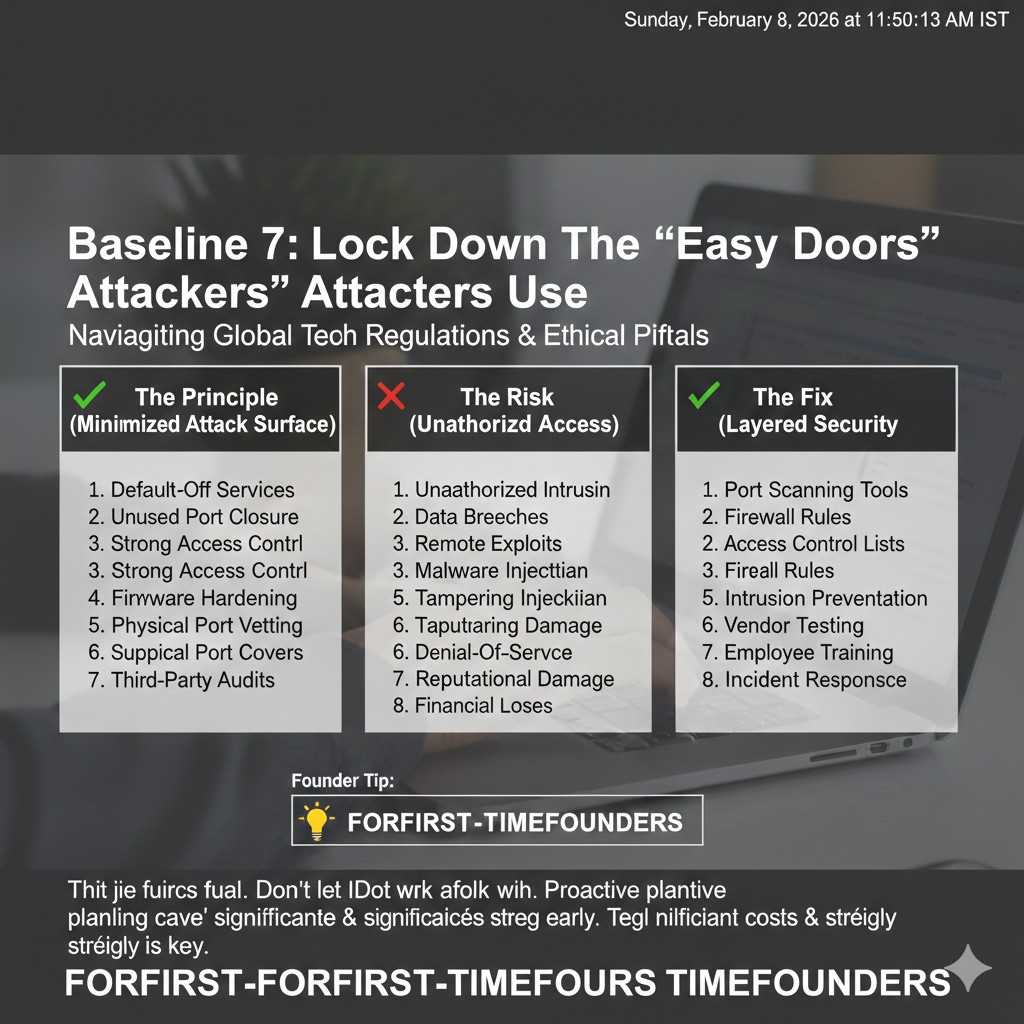

Lock down the “easy doors” attackers use

Most real breaches are not movie-style hacks. They are simple mistakes that stayed in the product because nobody owned them.

In robotics, common “easy doors” include default credentials, debug interfaces, and leftover test code.

Baseline 8: no default passwords, no shared passwords

Every robot should have unique credentials. If you ship a web UI, it cannot have “admin/admin” even in a hidden page. If you ship SSH access, it cannot use one shared key. If a customer sets a password, enforce minimum strength and block common weak choices.

If you must have a factory default, force a change on first use and block operation until it’s changed. For robots, the safest move is often to avoid local passwords entirely and use certificate-based identity plus short-lived tokens from your cloud.

Baseline 9: disable debug interfaces in production builds

JTAG, UART, debug shells, dev SSH keys, and “temporary” support endpoints are the classic way an attacker goes from “can touch the robot” to “owns the robot.”

Your baseline should include a clear production build mode that:

Turns off debug ports or requires a hardware action to enable.

Removes developer keys and test accounts.

Disables insecure services.

Locks boot settings.

This is where disciplined release engineering matters. Make it hard to ship a dev build by mistake.

Baseline 10: least privilege on the robot

Robots often run many processes: perception, planning, control, logging, UI, networking. If one part gets compromised, you don’t want it to control everything.

So the baseline is: processes run with the least privileges they need. Avoid running everything as root. Use OS sandboxing where you can. Use containers if that fits your stack, but do not treat containers as magic security by themselves. They help, but only when configured well.

Even small steps help. For example, your camera process should not be able to write to firmware partitions. Your navigation module should not be able to read your cloud credentials from disk.

Logs and data: keep what you need, protect what you keep

Robots produce rich data: video, audio, maps, location traces, user interactions, environment scans. This is valuable for debugging and ML. It is also sensitive.

Security is not only about stopping attackers. It is also about avoiding accidental leaks.

Baseline 11: do not log secrets, ever

It sounds simple. It is easy to fail.

Common secrets that end up in logs:

API keys and tokens.

Wi-Fi passwords.

Customer endpoints.

Internal IP addresses.

User emails and names.

Raw camera frames from private spaces.

Your baseline should include log scrubbing. If your team uses structured logging, build a redaction layer. Treat any field named “token,” “key,” “password,” “secret,” and similar as toxic. Block it from logs by default.

Also, protect logs at rest. If someone steals a robot, logs should not expose customer data. Encrypt sensitive storage, and set retention limits.

Baseline 12: clear data boundaries between customers

If you run a multi-tenant cloud, your minimum baseline must prevent cross-customer data mixing. Many startups do this right in the database, but forget about it in object storage, logs, analytics, and support tools.

A practical rule: every data object has an owner, and every access path checks that owner. This includes internal dashboards. Your support team is part of your threat model too, even if they are trusted. Mistakes happen.

This is a place where a clean architecture helps you scale sales. Larger customers will ask, “Can another customer see our maps?” If you can answer quickly and clearly, you win trust.

A simple baseline mindset: detect, respond, recover

Even with strong baselines, bad things can happen. A laptop gets stolen. A credential leaks. A supplier has an issue. A customer network is compromised.

So a minimum baseline includes basic detection and response.

You do not need a full security operations center. But you do need visibility.

Baseline 13: fleet visibility you can act on

At minimum, you should be able to answer:

Which robots are online right now?

What software version is each robot running?

When did each robot last check in?

Which robots failed an update?

Which robots showed strange auth failures?

Which robots are sending unusual traffic?

This is not only for security. It helps operations. It helps customer success. It helps engineering.

Build your control plane so it can flag odd behavior. Then define simple actions: quarantine a robot, revoke its cert, block its tokens, or limit its permissions until you investigate.

Baseline 14: incident playbooks for the basics

You do not need a thick binder. You need a few short, clear steps your team can follow under stress.

For example:

If we suspect a robot is compromised, how do we revoke it?

If a cloud key leaks, how do we rotate it?

If an update is malicious, how do we stop rollout?

If customer data is exposed, who is notified and how fast?

Write these down early. Keep them simple. Test them once in a tabletop exercise. You will find holes fast.

Architecture choices that make security easier

Draw a clear line between “robot brain” and “robot muscles”

A connected robot is really two systems living together. One part is the “brain” that plans, sees, and talks to the cloud. The other part is the “muscles” that move motors, brakes, and actuators. If the brain ever gets hacked, you still want the muscles to stay safe.

The minimum baseline here is separation. Your high-level computer should not have direct, unlimited power over motion. Put a safety controller or safety layer in between, even if it is simple at first. This layer should enforce speed limits, stop rules, and safe zones no matter what the cloud or the planner says.

This design changes the whole risk profile of your product. It also gives customers comfort, because you can explain that even if the network is hostile, the robot still obeys basic safety rules locally.

Keep safety rules local, not “in the cloud”

Cloud control is tempting because it feels flexible. But security and latency both suffer when safety depends on a network link. A minimum baseline is that the robot can always stop safely on its own, without waiting for a remote command or a remote approval.

You want a local “stop path” that is short and hard to break. If your software crashes, if the Wi-Fi drops, or if a remote attacker floods your network, the robot must still be able to hit a safe state.

This is not only about safety. It is also about reliability, which customers often value just as much as security.

Decide early what must never be reachable from outside

Most robot teams add services as they go. A debug dashboard appears. A telemetry endpoint becomes a control endpoint “just for now.” A local ROS bridge is exposed for a demo. Over time, the robot becomes a small city of open doors.

A minimum baseline is to name the “never expose” zones. Motor control, safety controller links, firmware flashing tools, and internal buses should not be reachable through any network path. If engineers need access, they should get it through a controlled, logged process.

This is a design decision, not a patch. If you decide it early, you avoid painful rewrites later.

Use a gateway pattern to shrink the attack surface

One of the cleanest ways to reduce risk is to route all external communication through a small, well-tested gateway process. This gateway is the only part that speaks to the cloud. Everything else talks only to the gateway over a local channel with strict rules.

When you do this, you reduce the number of network-aware components. That means fewer libraries, fewer open ports, and fewer chances to make a mistake. You also get one place to enforce rate limits, message validation, and authentication rules.

This is a common “minimum baseline” trick because it makes security work feel manageable for a small team.