Remote teams move fast. Global teams move even faster. But speed can hide cracks.

When co-founders live in different cities or countries, it is easy to assume you are “aligned” because you talk every day on Slack, ship code, and hit milestones. Then one hard moment shows up: a delay, a missed promise, a funding talk, a big customer, or a personal change. And suddenly the questions you never wrote down become the only questions that matter.

Who owns what?

Who decides what?

Who can sign what?

What happens if someone leaves?

What happens if someone can’t work for three months?

What happens if one founder wants to sell and the other does not?

A founder agreement exists for these moments. Not for the good weeks. For the tense ones.

If you are building AI, robotics, or any hard tech, the stakes are even higher. Your “product” is not just an app you can rebuild in a weekend. It is invention. It is know-how. It is models, data flows, control systems, edge cases, tests, designs, and small tricks you learned the hard way. If that value is not clearly owned by the company, you can lose deals, lose trust, and lose your leverage at the exact time you need it most.

That is why founder agreements for remote and global teams must be tighter than normal. Not harsher. Just clearer.

Here is the core idea: a good founder agreement is not a legal form you copy from the internet. It is a simple written “operating system” for how the founders will work together across time zones, borders, and pressure. It turns assumptions into decisions. It replaces hope with clarity.

And if you want to build a real moat early—before you raise big money—this is where it starts.

Tran.vc helps technical founders do this the right way from day one, including the IP side that most teams forget until it is too late. If you want help building a clean IP foundation while you build the product, you can apply anytime here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Before we go deeper, let’s make one thing very clear. Founder agreements are not about mistrust. They are about respect.

When you put terms in writing, you are telling your co-founder: “I care enough about this company to protect both of us. I want to be fair now, so we do not get unfair later.” That tone matters, especially when you are remote. Because distance makes small misunderstandings grow.

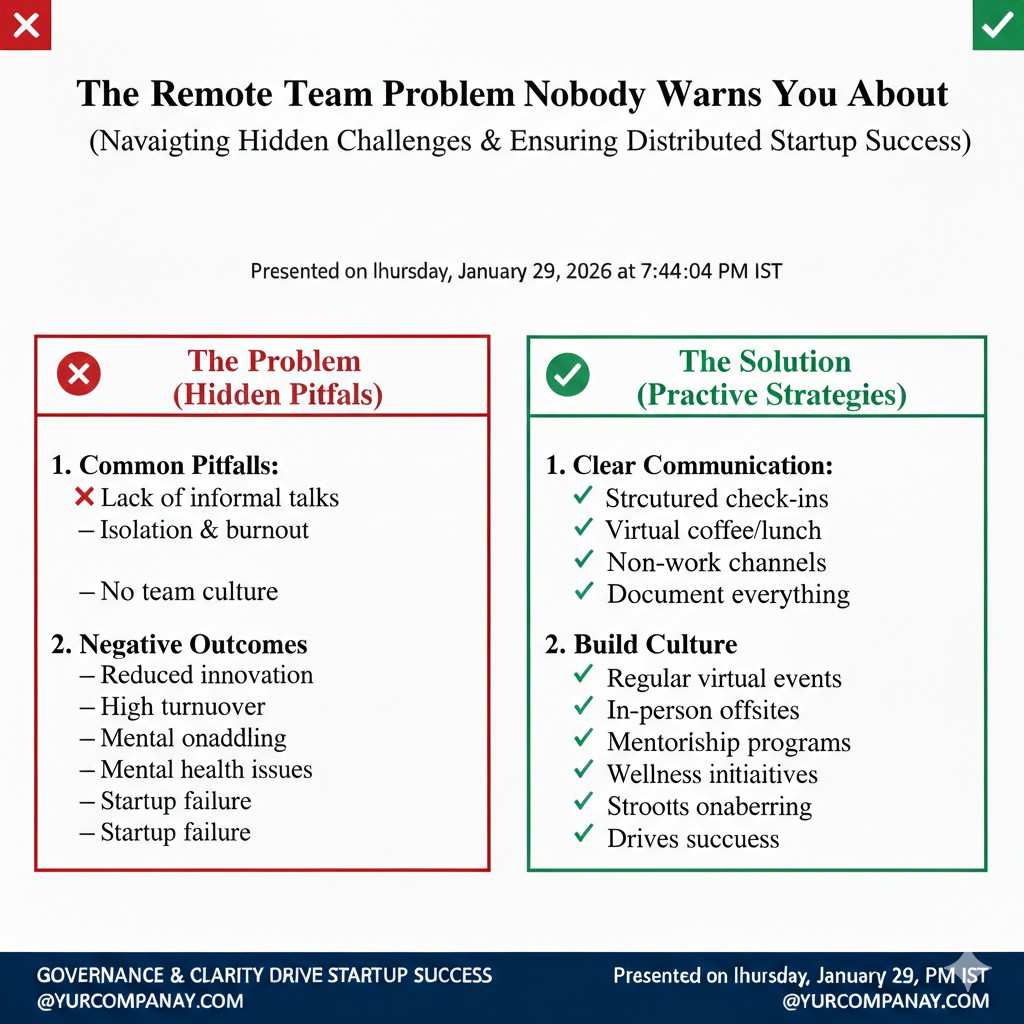

The remote team problem nobody warns you about

In-person teams solve many issues without noticing. You can see body language. You can tell when someone is burning out. You can pull someone aside after a meeting. You can sense when a decision is being avoided.

Remote teams do not get that. Remote teams get text. Calls. Calendars. And silence.

Silence is where problems hide.

Global teams also face real-world gaps: different laws, different tax rules, different holidays, different work norms, and different risk levels. One founder may be in a country where stock options are common. Another may be in a place where they are rare or taxed badly. One founder may be able to sign contracts easily. Another may need approvals. One founder may be under export limits or data rules. Another may not.

None of this means “do not build globally.” It means “write it down.”

What a founder agreement must do (in plain words)

A founder agreement should answer four big things:

First, it must say who owns the company and how that ownership grows or can be lost.

Second, it must say how decisions get made, especially when you disagree.

Third, it must protect the company’s work and inventions, so your IP is clean.

Fourth, it must say what happens when life happens: someone leaves, slows down, or disappears.

If your agreement does these four jobs well, you reduce founder risk. And founder risk is one of the top reasons investors say “no” even when they like the tech.

If you have ever heard, “We love the product, but we need to see the team tighten up,” this is often what they mean.

Why “handshake” deals fail faster in global teams

Many teams start with trust. That is normal. You build together, and you split the company 50/50. Or 60/40. Or you promise to “figure it out later.”

Later arrives fast.

One founder does more sales than expected. Another does more engineering than expected. Someone quits their job. Someone keeps a job “for safety” longer than planned. Someone moves countries. Someone gets a visa issue. Someone’s family needs support. Someone gets sick.

When you do not have clear rules, every change becomes a negotiation. Negotiations between tired founders are not fun. They feel personal because the company is personal.

A written agreement turns these moments into simple steps.

Start with the hardest part: ownership that matches reality

Equity splits feel like identity. People take them personally. Remote teams take them even more personally because you cannot “feel” the work the other person is doing. You only see outputs. And outputs are not always equal across roles.

So the goal is not to find the “perfect” split. The goal is to create a split that can survive pressure.

Most remote teams get into trouble for one of these reasons:

They split too early, before roles are clear.

They split evenly to avoid conflict, and then conflict shows up anyway.

They forget that commitment changes over time.

If you want the agreement to stay fair, you need one simple tool: vesting.

Vesting means you earn your shares over time, by staying and contributing. If you leave early, you do not keep all of it. This protects both founders. It protects the person who stays and carries the load. And it protects the company from having a big “dead” chunk of equity sitting with someone who is no longer building.

For remote and global teams, vesting is not optional. It is the seatbelt.

A common shape is four years with a one-year cliff. In plain words: if you leave before one year, you earn none. After one year, you start earning monthly or quarterly.

But do not treat this like a default checkbox. Talk about what “contributing” means in your team. Talk about what happens if someone is part-time for the first six months. Talk about what happens if one founder is doing full-time but the other founder can only do nights and weekends until a visa clears.

This is where remote teams need extra clarity. Because hours are invisible.

If you want a simple way to handle it, write down expectations for the first 90 days. Not as a long list. Just clear goals. For example: “Founder A will deliver v1 of the control loop and test rig. Founder B will run 20 customer calls and land 3 pilot LOIs.” Then revisit.

The agreement can say ownership is subject to vesting, and the board (or founders, if no board yet) can adjust role expectations when reality changes. That one sentence can save you later.

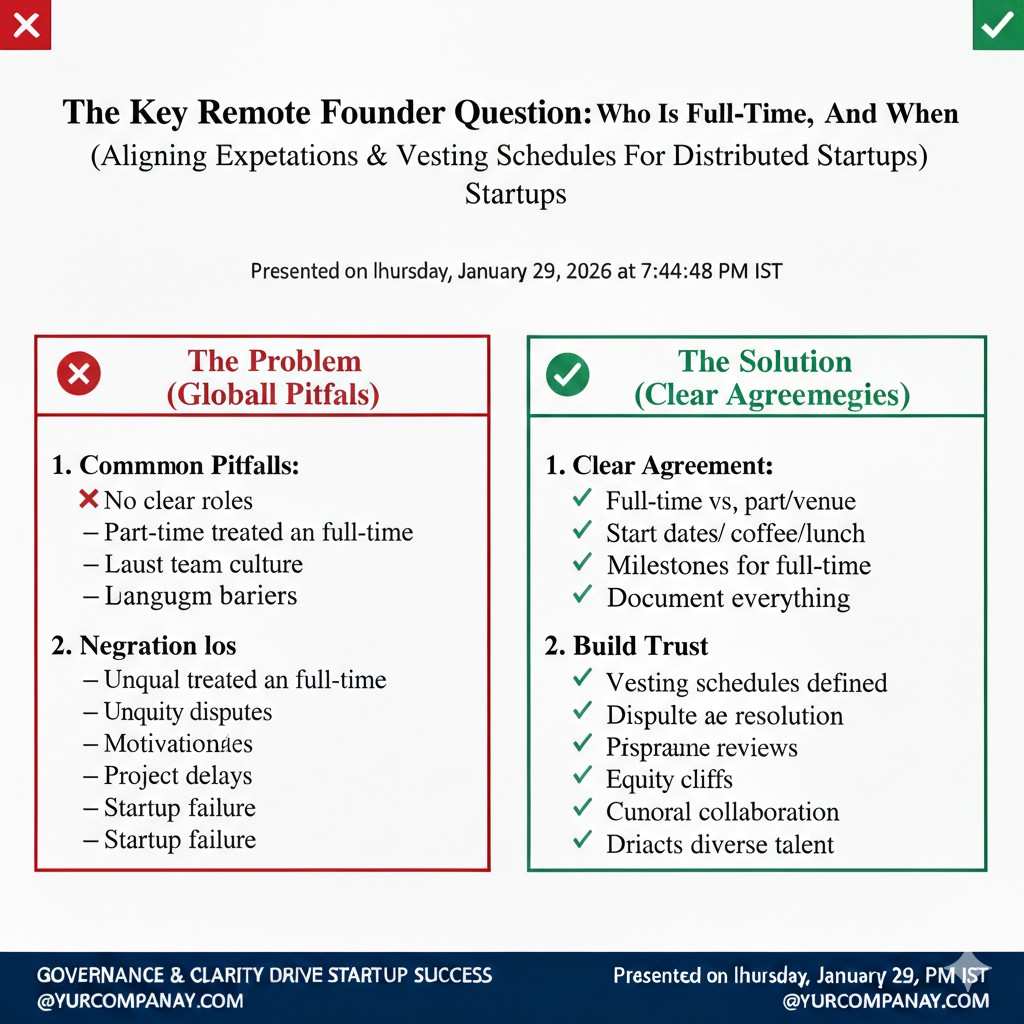

The key remote founder question: who is full-time, and when?

In global teams, “full-time” can mean different things. Some places work longer hours. Some places have strict labor rules. Some founders are still employed. Some are in school. Some are caring for family.

Avoid moral language here. Do not call someone “less committed” in the agreement. Just define what the company needs.

Write it like this, in simple terms: each founder has a target weekly time and a target start date for full-time work. If a founder cannot meet that, you define what happens. Maybe the vesting starts later. Maybe the equity is lower. Maybe the founder is treated as an early employee until they go full-time.

This is not punishment. It is matching ownership to risk.

When a founder goes full-time, they take real risk. When a founder stays part-time, they take less risk. The agreement should reflect that. Investors will also look for this.

Decision-making across time zones: the fastest way to avoid founder fights

Remote founders fight less often about “values” and more often about decisions. Who decides? When? Based on what?

The simplest solution is to define two types of decisions:

Small decisions: one founder can make them without asking.

Big decisions: both founders must agree.

The mistake is making the “big decision” set too large. Then nothing moves. The other mistake is making it too small. Then one founder feels ignored.

So think in terms of damage. A decision is “big” if it can hurt the company in a hard-to-reverse way.

In most startups, the high-damage items are: issuing shares, taking on debt, signing large contracts, changing the product direction, hiring or firing key people, moving IP out of the company, selling the company, or changing who can access core systems.

Remote teams also need one extra item: tools and access.

If your co-founder has admin access to the code repo, the cloud account, the model weights, the robot firmware, the CAD files, the data pipeline, and the domain, you need a clear rule for how access is managed. Not because you do not trust each other. Because accidents happen. Accounts get locked. People travel. Devices get stolen. One founder may also live in a place with higher risk of account takeover.

Your agreement should require shared ownership of key accounts, two-factor security, and a simple process for changing access. Investors love this. Future acquirers also love it.

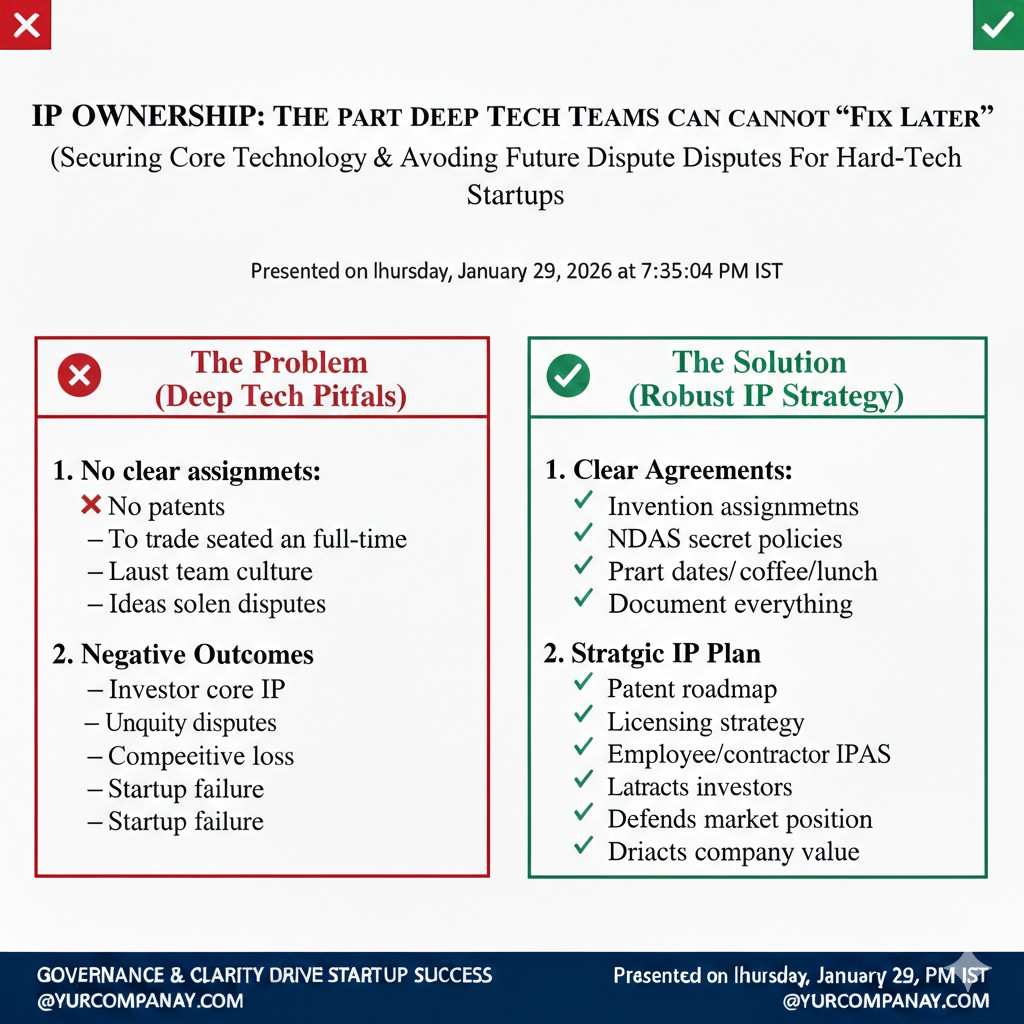

IP ownership: the part deep tech teams cannot “fix later”

Now we get to the part that matters a lot for Tran.vc’s world: IP.

In a remote and global team, inventions can happen anywhere. On a laptop in a cafe. On a home lab bench. In a university space. On a prior employer’s machine. During contract work. During weekend consulting.

This is where teams get hurt.

If one founder invents something and it is not clearly assigned to the company, the company may not fully own it. If the invention was made while working at a prior employer, the prior employer may claim it. If it was made in a university lab with grant money, the university may have rights. If a contractor wrote key code without a proper assignment, the contractor may own part of it.

And the worst part is: you often do not notice until diligence. That is when investors ask for proof that the company owns the work. If you cannot show it, the deal slows down or dies.

So your founder agreement must include a strong invention assignment. In simple words: “Any work we create for the company belongs to the company.”

But do not stop there. Global teams should also do two practical things:

First, keep invention notes. Nothing fancy. A shared doc where you write what you built, when, and who did it. This helps with patents and with clarity.

Second, decide early what is “company work” versus “personal work.” Remote founders sometimes build side tools or open-source pieces. That is fine if you handle it cleanly. The agreement should say what counts as side work and how you disclose it.

If you are building in AI or robotics, also watch out for training data and third-party code. The agreement should require you to track sources, licenses, and rights. This protects your future IPhttps://www.tran.vc/what-is-an-ip-moat-and-why-your-startup-needs-one/ and your future deals.

Tran.vc is built for this. They invest up to $50,000 in in-kind patent and IP services so your inventions become clean company assets, not messy stories you have to explain later. If you want that support, you can apply anytime here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Money, expenses, and founder pay: the quiet issue that becomes loud

Remote founders often avoid money talks because they feel awkward. Then they become explosive.

Your agreement should cover:

How expenses are approved.

How reimbursements work.

When founders can take pay, and how much.

What happens if one founder needs to take a small salary earlier due to cost of living or local rules.

In a global team, this matters because cost of living can vary a lot. Also, taxes and payroll rules vary.

The key is to set a principle. A simple one is: founder pay is low until revenue or funding, and any pay must be approved by both founders. If you need flexibility, you can write: “If a founder needs pay for basic living, we will agree on a small amount and treat it as a company expense with full transparency.”

Transparency is the real rule. When money is hidden, trust breaks.

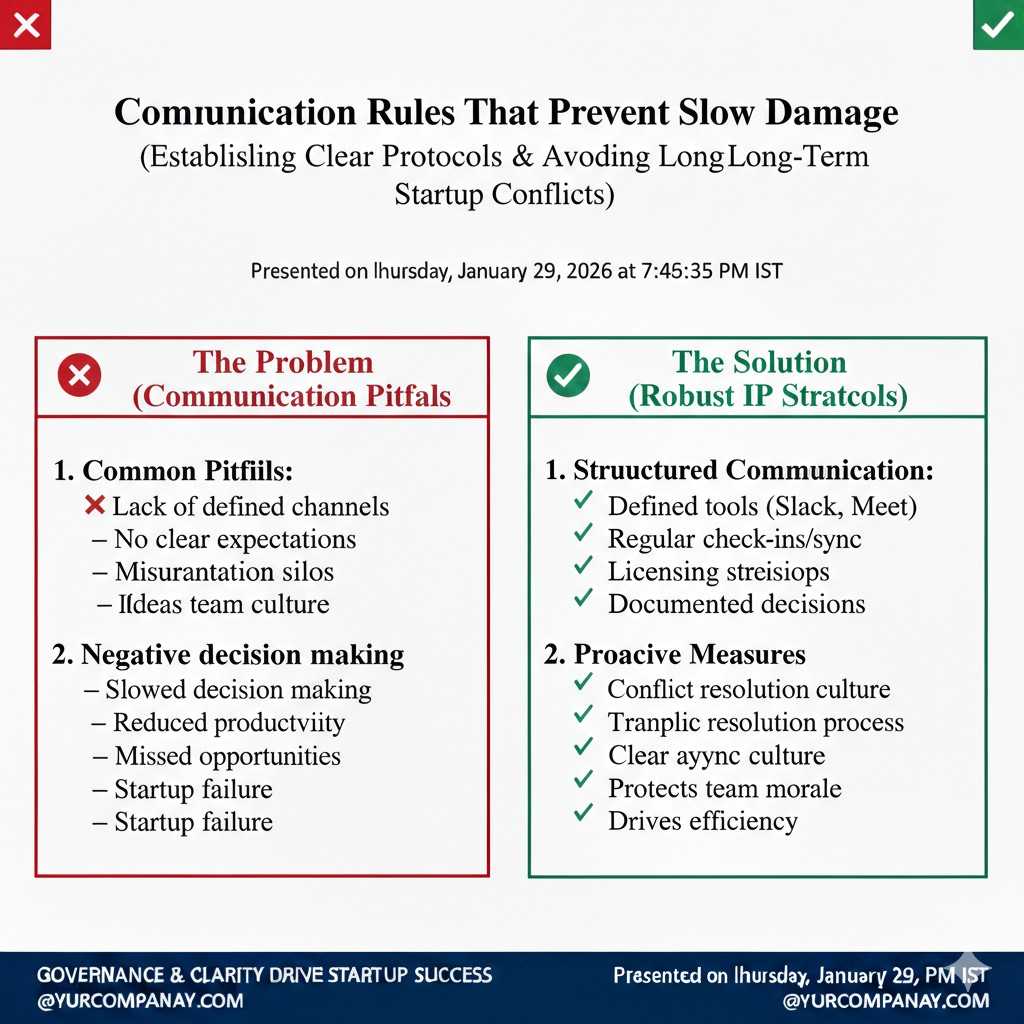

Communication rules that prevent slow damage

Most remote founder trouble does not start with betrayal. It starts with drift.

One founder feels out of the loop. One founder feels like they carry the weight. One founder feels like their work is not valued. These feelings grow when communication is weak.

So your agreement should include light but real communication expectations.

Not a long list. Just a clear rhythm.

For example, a weekly founder call that cannot be skipped without notice. A short written update each week. A rule that hard topics go on a call, not in text threads. A rule that decisions are written down after the call, so memory does not rewrite history.

This may sound small. It is not.

A founder agreement is not just legal. It is behavioral. It shapes how you act when you are tired.

What happens if a founder leaves

This is the part many teams avoid because it feels negative.

But it is the part that protects the company the most.

If a founder leaves, you need answers to these questions:

Do they keep vesting?

Do they keep any unvested shares?

Do they keep a board seat?

Can they start a competing company?

Can they recruit your employees?

Can they use your code or inventions?

How do you handle their access and accounts?

A good agreement makes these outcomes clear and fair.

For remote teams, also plan for “soft leaving.” A founder may not quit, but may slowly stop showing up. This is more common than a clean exit. Your agreement should define what “inactive” means (for example, missing meetings and not delivering work for a set time) and what happens then.

This protects both people. It prevents endless limbo.

One more thing: global legal reality

If your founders are in different countries, you must be careful about which country’s laws govern the agreement, and where disputes are handled. This is not a detail. It can decide whether your agreement is easy to enforce or hard to enforce.

Also, the type of entity you form matters. Many startups incorporate in Delaware (for U.S. investors), but the founders may live elsewhere. That creates tax and reporting issues. The agreement should not pretend those issues do not exist.

This is where good counsel helps.

Tran.vc’s model is built around helping early founders build strong foundations, including clean IP and good structure, without forcing you to chase VC money too soon. If you want to build your moat early and avoid painful fixes later, apply here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Founder Agreements for Remote and Global Teams

Why this document matters more when you are not in the same room

When founders work in different places, the company runs on written words. Your chats, your docs, your contracts, your calendars, and your code comments become the “office.” If the founder agreement is vague, your company is vague too, even if you are shipping fast.

A founder agreement is not a sign that you do not trust each other. It is a sign that you are serious enough to protect the friendship and the company at the same time. It helps you avoid the kind of slow confusion that remote teams often mistake for “normal startup stress.”

The goal is simple: remove guesswork before it becomes conflict. You do this by writing down how ownership works, how decisions get made, how inventions belong to the company, and what happens when someone steps back. That is how you build a company that can survive pressure.

If you want support building a clean IP and legal foundation from day one, you can apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

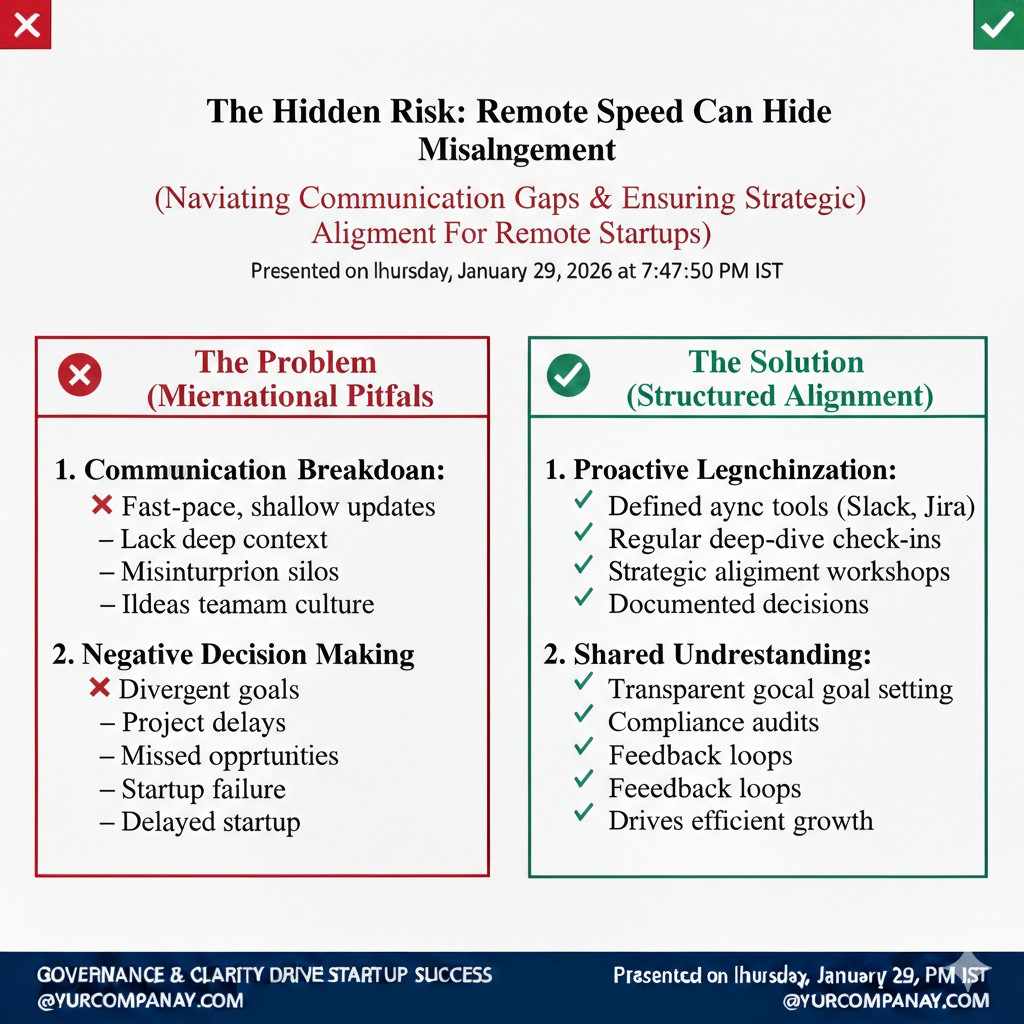

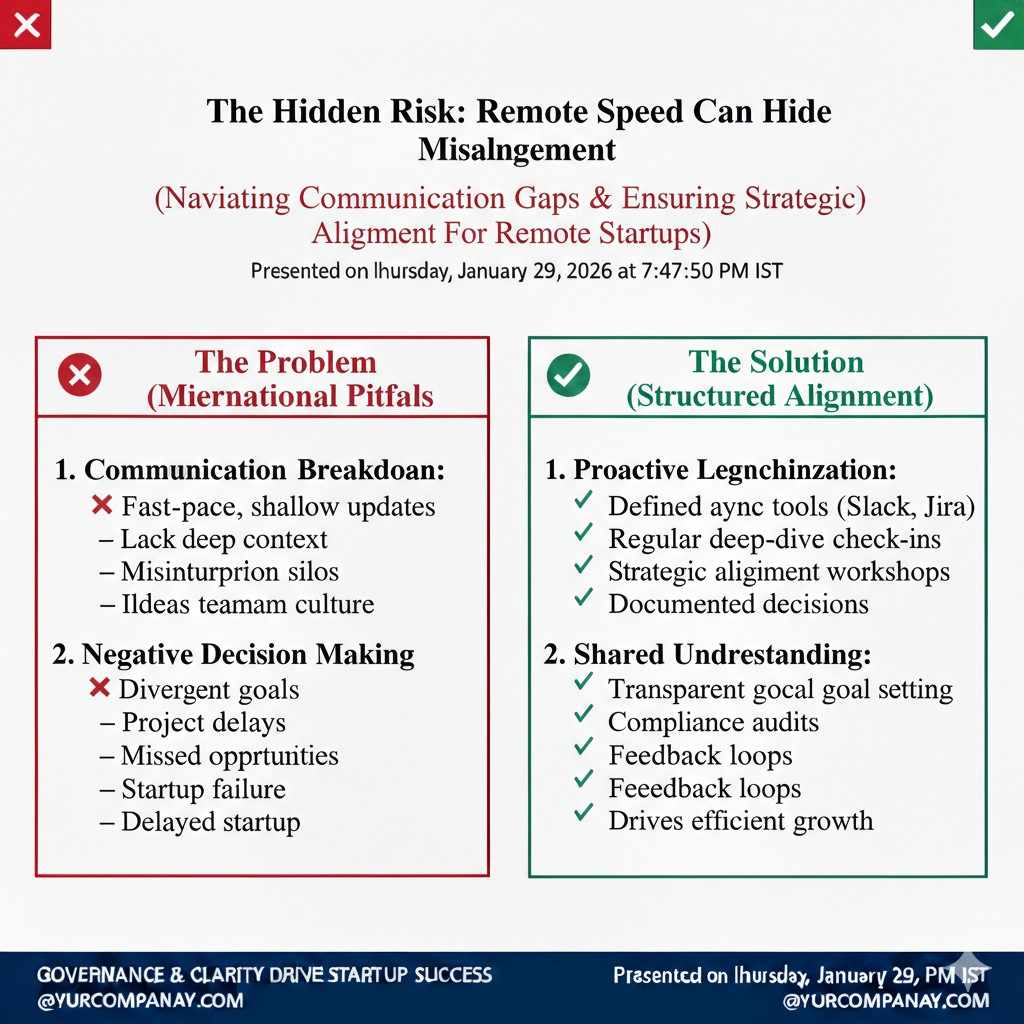

The hidden risk: remote speed can hide misalignment

Remote teams can move very fast because they skip small talk and jump straight to tasks. Global teams can move even faster because work can happen around the clock. But speed can hide the fact that founders are making different assumptions about the same topic.

One founder might assume the company is a long-term project. Another might assume it is a quick sprint to a seed round. One founder might assume “we share everything.” Another might assume “we each own our parts.” These are not small differences. They decide how you hire, how you spend, and how you negotiate.

A strong agreement brings these assumptions into the open in a calm way. It makes the hard talks easier because the document gives you a shared structure. That structure matters even more when you cannot read body language and you cannot fix tension with a quick hallway chat.