Freedom to Operate—often called “FTO”—is one of those topics most startup founders hear too late.

At first, things feel simple. You build fast. You ship. You talk to users. You sign pilots. Your product starts working. Then one day, an investor asks a sharp question: “Have you done an FTO?” Or a big customer’s legal team sends a long form that includes a line like: “Please confirm your solution does not infringe any third-party patents.”

That’s when many founders realize something uncomfortable: building a product and being allowed to sell it are not always the same thing.

FTO is about risk. Not fear. Not theory. Risk. It is the practical work of checking whether your product might step on someone else’s patent rights in the places you plan to sell. It does not matter if you wrote every line of code yourself. It does not matter if your engineer “invented it independently.” Patent law does not work like copyright. If a patent claim covers what you do, you can still get blocked, even if you never saw that patent in your life.

This is why FTO matters so much for robotics, AI, and other deep tech. These fields are crowded. There are big companies with wide patent walls. There are also small firms that earn money mainly by enforcing patents. And there are patents that look harmless until you read the claims and realize they map to real product features.

The good news: you do not need to panic. You just need a plan. The smartest founders treat FTO like they treat security or safety. They do enough early to avoid obvious landmines, then they go deeper when the business calls for it.

If you want help building that plan with real patent experts—so you can move fast without stepping blind—you can apply to Tran.vc anytime here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

What FTO Really Means

FTO is a selling-rights check, not an invention check

Freedom to Operate means this: can your startup make, use, and sell your product without likely breaking someone else’s patent rights in the countries you care about.

It is not a badge you earn once and then forget. It is a risk check tied to what you ship today, what you will ship next, and where you plan to do business.

Think of it like this. You can build a great robot arm or a strong AI model, and still have a problem if a patent claim covers a key part of how your system works. FTO helps you see that risk early, while you still have room to adjust.

Why the word “operate” matters more than people think

The word “operate” is the clue. Patents can block activity, not ideas. If your product does certain steps, or has certain parts, and those match what a patent claim says, you may have a problem.

Many founders assume patents only matter if you copied. That is not how it works. Patents can be enforced even when you built everything from scratch.

So FTO is not about proving you are original. It is about reducing the odds that someone can stop you, delay you, or force you into a costly deal.

FTO is never “perfect,” but it can be strong

No honest patent attorney will promise “zero risk.” There are too many patents, and new ones publish every week.

But FTO can still be strong. Strong means you searched in a smart way, you looked at the right claim sets, and you made clear choices about what to change, what to keep, and what to watch.

This is how serious startups behave. Not because they are scared, but because they want control.

If you want Tran.vc to help you do this in a founder-friendly way—without slowing product speed—you can apply here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

What FTO Is Not

FTO is not the same as a patentability search

A patentability search asks: “Can I get a patent on my invention?” It is about your novelty and how different you are.

FTO asks a different question: “Can I sell my product without likely infringing?” That is about other people’s claims, not your own.

A startup can pass a patentability search and still fail an FTO review. That surprises many teams, but it is common.

FTO is not a guarantee, and it is not legal “insurance”

Some founders treat an FTO like a shield they can hold up in court. That is not what it is.

FTO is a process and a set of findings. It shows you acted carefully and made informed choices. That can help in business talks, and it can help in legal strategy, but it does not erase risk.

It also does not replace good contracts, good product records, and good internal discipline.

FTO is not only for “later,” and not only for big companies

It is easy to think FTO is something you do after Series A, once you are “real.” That idea is costly.

The truth is that risk grows as you get traction. The moment you have customers, revenue, or a visible product, you become easier to target.

Startups do not need the same deep review as a Fortune 100 company on day one. But they do need the right level of FTO at the right time.

Why FTO Hits Robotics, AI, and Deep Tech So Hard

Hardware makes patents easier to map to products

In software, features change quickly and can be harder to pin down. In robotics and hardware, parts and systems are more fixed.

A gripper design, a sensor placement method, a calibration routine, or a motion planning pipeline can remain stable for months. That stability is great for building, but it also makes it easier for someone to compare your product to a patent claim.

That is why robotics startups often feel patent pressure earlier than pure software teams.

AI is not “safe” just because it feels abstract

Many AI founders assume patents cannot cover models or training. That is a risky assumption.

There are patents on data pipelines, feature extraction, training workflows, model deployment, edge inference setups, system-level feedback loops, and many other practical pieces.

Even if the math feels universal, the way you implement the system can overlap with existing patent claims.

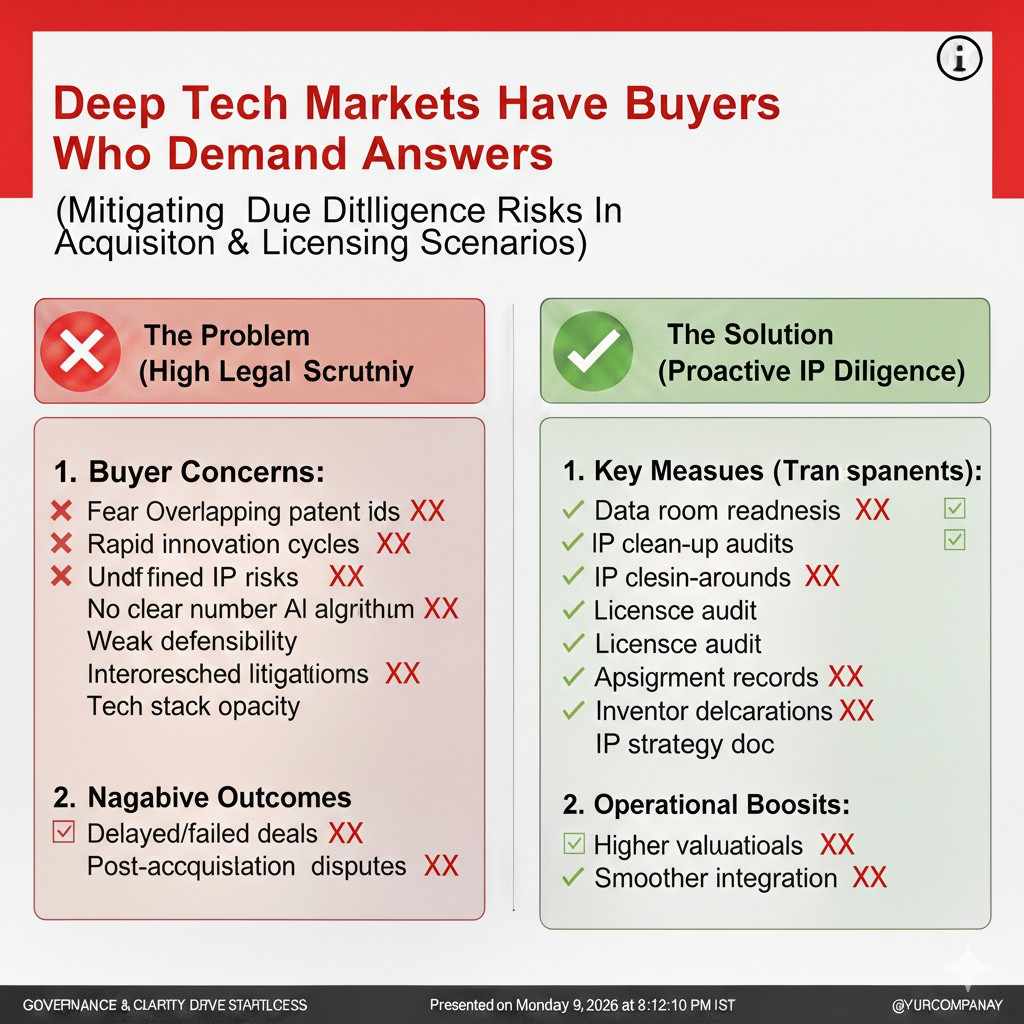

Deep tech markets have buyers who demand answers

Enterprise buyers and large channel partners often ask for proof that you have thought about IP risk.

Sometimes they do it during procurement. Sometimes they do it after a pilot when they want to roll you out widely. Sometimes they do it because their own legal team is cautious.

If you cannot answer clearly, you may not lose the deal immediately, but you will create delay. Delays kill momentum.

If you want guidance that keeps deals moving, Tran.vc can help you build clean IP answers early. Apply anytime: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

When You Need FTO

The “idea stage” is for light checking, not heavy work

If you are still exploring the problem and building a first prototype, a full FTO is usually too early.

But doing nothing can also be a mistake, especially in crowded spaces like warehouse robots, surgical robotics, autonomous navigation, or well-known industrial AI use cases.

At this stage, you want quick checks. You want to spot obvious patent thickets and see who owns the space. This helps you choose safer paths before your design becomes fixed.

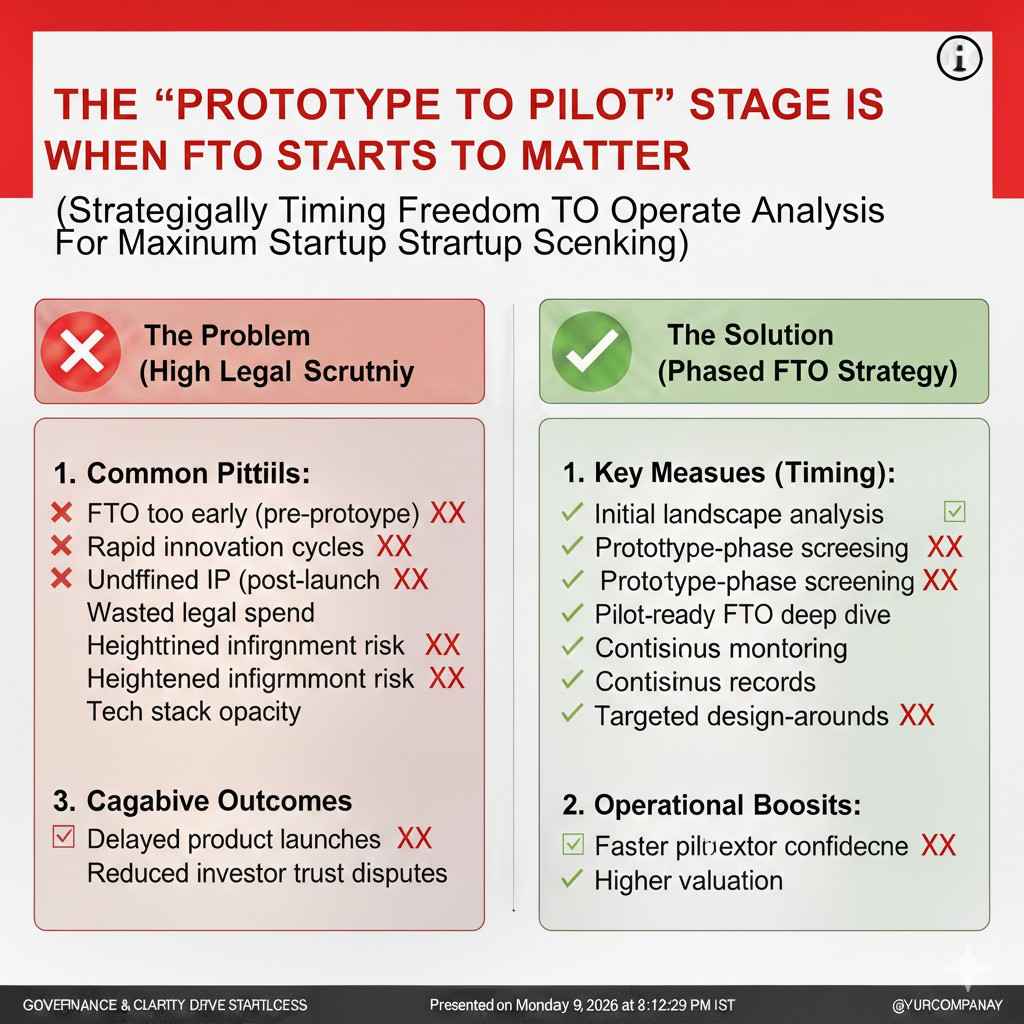

The “prototype to pilot” stage is when FTO starts to matter

Once you have a working prototype and you are planning pilots, you should begin a more focused FTO effort.

This is when your system has real shape. You know your core features. You know what makes your approach different. You can list the functions you must keep, and the ones you can change.

That clarity makes the FTO work faster and more useful. It becomes tied to real product decisions, not guesses.

The “first big customer” stage is where FTO becomes a deal tool

A large customer can change everything. It can also bring deeper scrutiny.

Big customers do not only buy products. They buy risk profiles. If they think your product may create patent trouble for them, they may walk away, or they may ask for strong protection terms that you cannot accept.

This is where FTO can support confidence. It helps you speak in a calm, clear way and show you have done your homework.

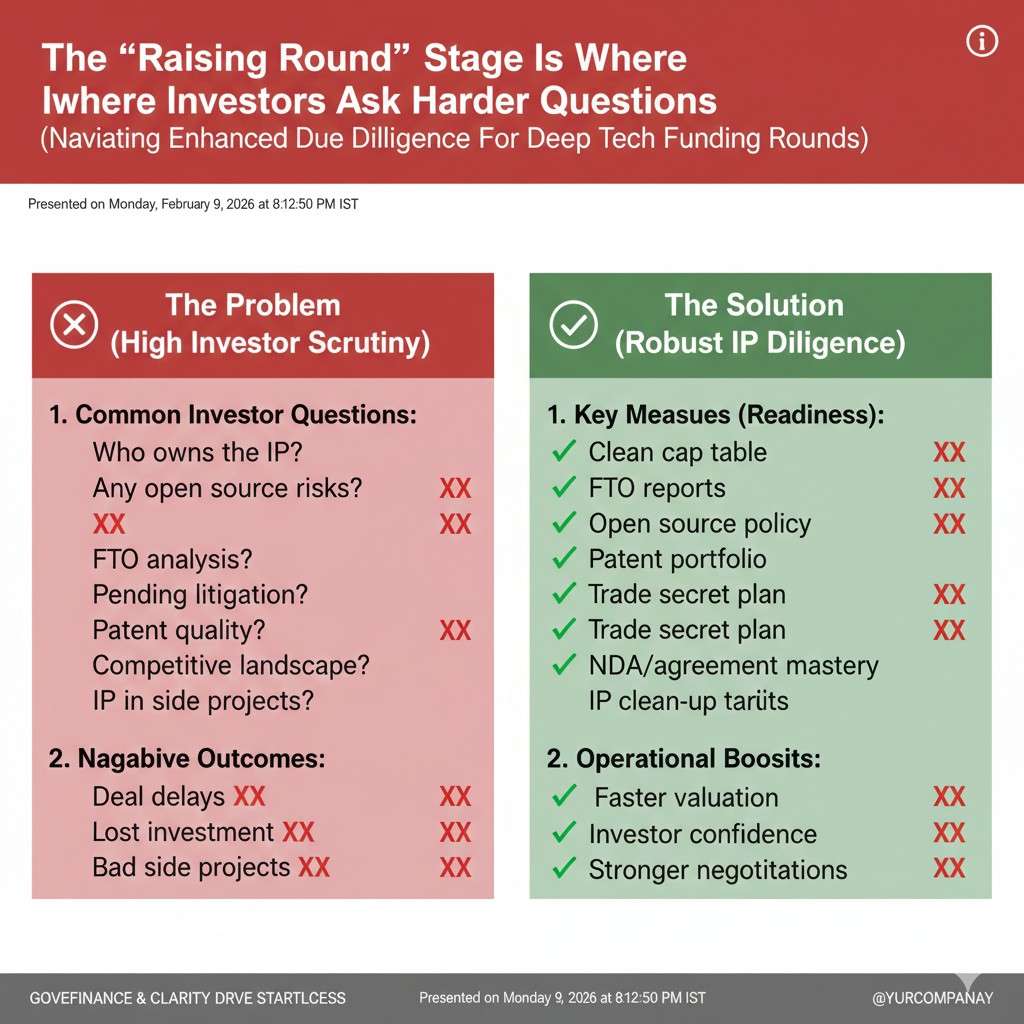

The “raising round” stage is where investors ask harder questions

Many founders are surprised that investors care about FTO. They do, especially in deep tech.

Investors want to know two things at the same time. First, do you own something defensible? Second, are you likely to be blocked while scaling?

Even if your tech is strong, a hidden patent risk can turn a high-growth plan into a slow legal mess. That risk affects valuation and speed.

How FTO Work Differs from Getting Your Own Patents

Your patents create a fence, but FTO checks for landmines

A patent you own can help you defend your position. It can scare off copycats. It can support licensing. It can make your company more valuable.

But your patents do not automatically give you the right to operate. This is the part many founders miss.

You can own a patent and still infringe someone else’s broader patent. Both can be true at the same time.

FTO looks at claims, not just titles and abstracts

A patent’s title can be misleading. The abstract can be vague. The drawings can look unrelated.

The real power is in the claims. Claims are the lines that define what is protected.

Good FTO work is claim-focused. It maps claim elements to real product elements. It does not stop at “this sounds similar.” It asks, “Does our product do each part of this claim?”

FTO leads to action, not just a report

A report that sits in a folder is not the point.

FTO work should lead to choices. You may decide to change a feature. You may choose a different design path. You may plan a license talk. You may decide the risk is low and keep moving.

The value is not the paper. The value is the control it gives you.

If you want Tran.vc to support this with patent experts who understand startup speed, apply here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

The Main Outcomes You Want From an FTO

A clear view of what could stop you

The goal is not to find every patent in the world. The goal is to find the patents most likely to matter.

That usually means patents owned by companies active in your market, with claims broad enough to map to your product, in the countries where you plan to sell.

Once you see those, you can plan. Planning is what reduces fear.

A simple set of design “must-keep” and “can-change” parts

The best FTO process forces clarity.

You learn what parts of your product are core. You learn what parts are flexible. You stop arguing in circles.

That clarity is also great for engineering focus. It helps teams build faster because they know where to hold steady and where to adapt.

A record that shows you acted responsibly

If you ever face a patent dispute, it helps to show you took risk seriously and made informed decisions.

This is not a promise of safety. But it is better than looking careless.

It also helps in business talks with partners, customers, and investors, because you can speak with structure and calm.

How to Think About FTO Scope Without Getting Lost

Start with what you will sell, not what you might build someday

FTO should match the product you are shipping or about to ship.

Startups often try to cover every future idea. That makes the work too big and too slow.

Instead, focus on the current version and the next planned release. You can update the FTO as the product changes.

Choose countries based on real sales plans

Patents are country-based. A U.S. patent matters in the U.S. A European patent matters where it is validated.

So you do not need to search everywhere at once. You need to search where you will operate.

If you plan to sell in the U.S. and Europe first, start there. If your first customers are in Japan or Korea, that matters too.

Focus on the riskiest features first

Not every feature has the same risk.

Features that are common in the industry, or that are widely described in competitor marketing, often have more patent coverage.

Core technical steps, like how you localize a robot, fuse sensor data, schedule motion, detect defects, compress a model, or deploy inference on edge devices, may carry higher risk than UI details.

A good scope starts with the features that create value and are hard to replace.

Freedom to Operate (FTO) for Startups: When You Need It and Why

How an FTO Is Done in Real Life

The work starts with your product, not with a patent database

A useful FTO begins with a clear picture of what you are building today.

Not the pitch deck version. Not the “future vision” version. The real version that will be in a customer’s hands, or in their factory, or running in their cloud.

This matters because patents are compared to what your product does, step by step. If your description is fuzzy, the search will be fuzzy too. When founders say, “Our product uses AI,” that is not enough. AI can mean many things. But if you say, “We use a camera feed, detect objects, track them across frames, predict motion, and then plan a path,” that is a real chain of actions. That chain can be checked.

So the first step is often a structured product walk-through. A founder or technical lead explains the system in plain terms. Then the patent team turns that into a set of search themes tied to actual functions.

The best input is a simple technical story anyone can follow

Many startups think they need to hand over dense documents.

In practice, what works best is a clean explanation of the system that makes sense even to a smart person outside your niche.

For robotics, this might include how you sense the world, how you decide what to do, and how you control motion. For AI, this might include how you collect data, how you train, how you serve predictions, and how you monitor performance.

You do not need fancy words. You need a stable story that matches your product.

The side benefit is that this story becomes useful in many places. It helps with onboarding, with customer talks, and with investor due diligence. A strong FTO process often improves company communication.

The search is built around “claims,” but the map comes first

A patent search without a map is like walking into a library with no topic in mind.

The map is your feature set. It is the list of product parts that matter, described in a way that can be searched.

For example, “robot navigation” is too broad. But “visual-inertial odometry with loop closure in indoor spaces using a pre-built sparse map” is more specific and searchable.

The team then looks for patents that appear close to those features. But they do not stop at what “seems similar.” They read the claims, because the claims define the boundary.

You are not searching for “who did it first,” you are searching for “who can block you”

This is an important mindset shift.

FTO is not a history project. It is not about who invented an idea earliest. It is not about which lab wrote a paper.

It is about enforceable rights. Some rights are broad. Some are narrow. Some are expired. Some are not active in your target country. Some were filed but not granted. Some look scary but are easy to design around once you understand the claims.

So the search aims to find patents that are both relevant and powerful enough to create risk.

The analysis step is where most value is created

Many founders assume the value is in finding patents.

The real value is in analyzing them.

A good analyst breaks a claim into parts, then checks your product against those parts. If one part is missing, you might not infringe that claim. If every part seems present, risk is higher.

This is why “reading patents” is not a casual task. Patent language is designed to be precise and to stretch. It often sounds odd because it is built to cover many variations.

The output should not be “we found 100 patents.” It should be “here are the few that matter, here is why, and here are your options.”

If you want Tran.vc to help you run this process with experienced patent attorneys who understand early-stage reality, you can apply anytime: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

The Key Distinctions Inside FTO Work

A quick scan is not the same as a true FTO review

Some teams do a fast search on Google Patents and feel done.

That kind of scan can be useful early, but it is not a real FTO.

A real FTO review is structured. It has a defined product scope. It is focused on claims. It checks jurisdictions. It documents reasoning. It gives action steps.

A scan is like checking the weather by looking outside. It helps, but it is not the same as reading a forecast when you are planning a long trip.