Priority is your place in line.

In patents, being first in line often matters more than being “better.” If you lose priority by accident, you can end up in a painful spot: your own pitch deck, demo day, blog post, GitHub commit, customer pilot, or even a casual talk can become the thing that blocks your patent later. Even worse, a competitor can file after you—but if you slip up and lose your priority date, they may look “earlier” than you on paper.

This happens to smart founders all the time. Not because they are careless. Because early-stage building is fast, messy, public, and full of little decisions that seem harmless in the moment.

At Tran.vc, we see priority mistakes most often in AI, robotics, and deep tech teams. The work is technical. The timelines are tight. You’re hiring, shipping, fundraising, and trying to show traction. You want to talk about what you’re building. That’s normal. But patents have their own rules, and priority is the rule that bites founders when they least expect it.

This article is about how to avoid losing priority by accident. Not in theory. In the real day-to-day of a startup.

And if you want experienced patent help from day one, Tran.vc can invest up to $50,000 in in-kind patent and IP services so you can build a moat early without burning cash. You can apply anytime here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Now let’s make priority feel simple.

Priority is the date the patent office treats as your “first filing date” for a specific invention. When you hear people say “file early,” what they really mean is “lock in priority early.”

But here’s the detail most founders miss: you don’t “own” a priority date just because you had the idea first, or built a prototype first, or wrote code first. Priority is tied to what you actually filed, and what that filing clearly teaches. If your filing is thin, vague, or missing key pieces, you may not get priority for the later details you add. Those later details might get a later date. That is how people lose priority without realizing it.

So the big risk is not only missing a filing deadline. It’s also filing something that doesn’t fully cover what matters, then assuming you’re safe.

Let’s walk through the common ways founders lose priority, the warning signs, and what to do instead.

The silent priority killer: talking before filing

Startups survive on talking. You talk to customers, partners, investors, press, advisors, talent, and other founders. In robotics and AI, you also talk at meetups, publish benchmarks, share demos, open-source pieces, and write technical blogs.

Every one of those can create a “public disclosure.” And public disclosure can ruin your ability to patent in many countries. In the United States, there is a one-year grace period for many disclosures made by the inventor, but you should not treat that as a safety net. First, it does not work the same way everywhere. Second, it creates uncertainty. Third, investors and acquirers hate uncertainty in core IP.

Here’s what “public” can mean in practice:

If you post details on LinkedIn, it is public.

If you tweet a diagram, it is public.

If you put a detailed write-up on your website, it is public.

If you upload a repo with the key method, it is public.

If you present at a meetup where anyone can attend, it is public.

If you demo the key inner workings in a talk that is recorded, it is public.

If you publish a paper or preprint, it is public.

Founders often say, “But I didn’t give away the whole thing.” The problem is you don’t need to give away the whole thing to create risk. If what you shared is enough for a skilled person to understand and recreate the core idea, it can count.

Also, sometimes you don’t even realize you disclosed the key part. A single slide with a system diagram. A single line in a README. A single screenshot of a training pipeline. A single performance chart paired with method details. A single “here’s how we do it” paragraph.

If you want to avoid losing priority, you need a habit: file before you talk.

Not “file when you’re ready.” Not “file after the round closes.” Before you talk.

That doesn’t mean you need a full, expensive, final patent every time. In many cases, teams use a provisional filing to lock a date early. Then they build on it with later filings as the product changes. But the key is this: the provisional must be solid. It must actually teach the invention.

This is where Tran.vc helps teams move fast without being sloppy. We plan filings around your real roadmap: what you will ship, what you will demo, what you must share to raise, and what must stay protected. If you want that kind of founder-first IP plan, apply here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

The second silent killer: filing too thin, then “updating” later

This is the trap that feels like you did the right thing, but still fails.

A founder rushes to file a provisional. They write a few pages. They include a high-level description. They paste a few figures. They file it the night before demo day. They feel safe.

Then six months later, the product is clearer. The method is sharper. The real novelty is now obvious. They file again with the real detail.

Here’s the issue: your priority date for the real novelty is not the early date unless the early filing actually included it, clearly.

Patent priority is not a blanket shield. It’s specific. Each claim in your later patent needs support in the earlier filing if you want the earlier date for that claim.

So when teams ask, “We filed a provisional last year, so we’re good, right?” the honest answer is: maybe. It depends on what was in it.

This is why “file early” is incomplete advice. The better advice is:

File early, and file enough.

Enough means:

Clear description of the problem you solve.

Clear description of the system and steps.

Multiple variations so you’re not boxed in.

The key technical choices and why they matter.

Examples, flows, and alternative versions.

Details that show you actually possess the invention, not just wish for it.

Again, this does not need to be long for the sake of being long. It needs to be complete for the part that matters.

In AI and robotics, thin filings often fail because the novelty lives in details: how the data is formed, how the model is trained, how control loops are stabilized, how sensors are fused, how policies are constrained, how compute is reduced, how edge cases are handled, how the system stays safe, how you get repeatable results, how you close the sim-to-real gap.

If you file a vague story like “we use machine learning to optimize control,” you may not get priority for the real technique you later claim, like a specific way of building a training curriculum, a special loss, a structured latent space, a constrained policy, or a sensor gating method.

So the action step here is simple: treat a provisional like a real technical document, not a placeholder.

If you’re unsure what “enough” looks like, this is exactly the kind of thing Tran.vc supports. We help you capture the real invention in a way that stands up later, so you don’t wake up to a priority problem when you finally file the non-provisional. Apply anytime: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

The third killer: assuming NDAs fix everything

NDAs are useful. But they are not a magic shield.

Founders often think: “We’re safe because we had them sign an NDA.” Sometimes you are. Sometimes you’re not. And sometimes you can’t prove it.

Here’s why this gets messy:

Investors often will not sign NDAs.

Some partners will sign, but their process is sloppy.

Someone forwards your deck internally.

You present to a group and one person in the room didn’t sign.

You send a deck, and the deck gets shared.

You discuss details in a call, but the NDA wording doesn’t cover that kind of disclosure well.

You rely on an email thread as “proof,” and it’s not clean.

Also, even if you had an NDA, there can still be a priority issue if you later file something that is not fully supported by your earlier filing. The NDA doesn’t fix a thin filing.

So the safer mindset is: NDAs reduce risk, but filings create rights.

Use NDAs when you can, but do not use them as the reason to delay filing.

The fourth killer: not knowing what counts as “the invention”

This sounds basic, but it’s the root cause of many priority accidents.

In deep tech, the “invention” is rarely the whole product. It’s usually a specific technical method or system that makes the product work better, cheaper, faster, safer, or more reliable.

Founders sometimes file on the broad product idea, like “a robot that picks items.” That is not the invention. That’s the goal.

The invention might be the grasp planning method that works with cheap sensors. Or the calibration routine that adapts online. Or the way you combine vision and force to avoid slip. Or the safety constraint that keeps the arm within limits even when the model is wrong.

If you don’t name the true invention early, you may file the wrong thing first. Then you talk publicly about the real breakthrough later, thinking the first filing covers it. It might not.

A practical way to avoid this is to keep a running “invention log” inside the company. Not fancy. Just a habit. Every time the team solves a hard technical problem in a new way, write down:

What was the problem?

What did we try that failed?

What did we change that made it work?

What are two other ways it could be done?

What data or results show it works?

This forces clarity. It also gives your patent counsel the raw material to write a filing that actually earns the priority date.

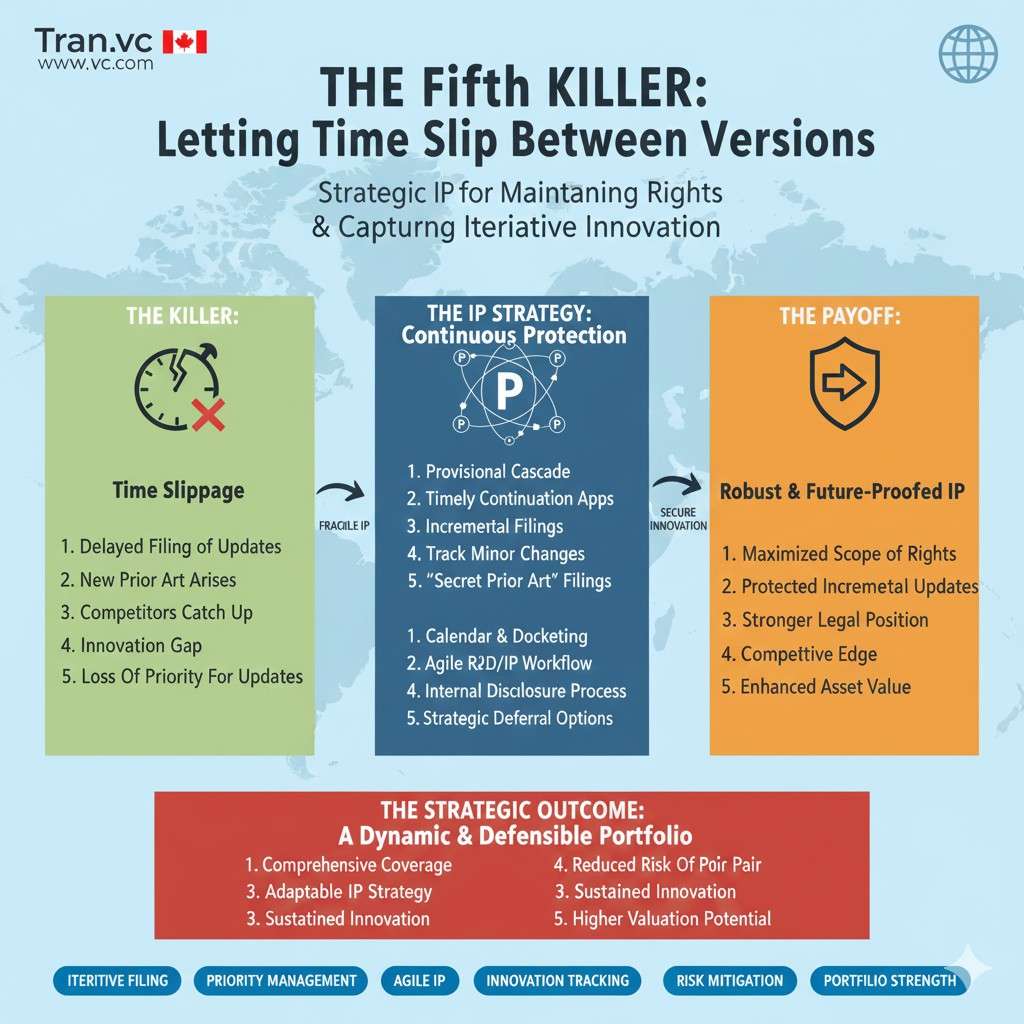

The fifth killer: letting time slip between versions

Priority is also lost in a more boring way: time passes.

A team files a provisional. They keep building. The product changes. The next filing is late. In the meantime, they release features, show demos, and publish results that relate to the improved version, not the old version.

Now there’s a gap. And the gap is where risk lives.

This shows up in AI a lot, because models evolve. Your early method might be good, but your later method is the one that wins. If you keep talking about the later method, but only filed the early one, you may have a patent posture that doesn’t match reality.

The fix is not “stop building.” It’s to align your IP timeline with your product timeline.

If you know you will announce a big new capability in March, do not wait until March to file. File before the announcement. If the method is still moving, file a version that captures what’s stable, plus variations that likely cover where it’s going.

A good IP plan is not a one-time event. It’s a rhythm.

At Tran.vc, this rhythm is what we build with founders. We treat IP as part of execution, not paperwork. You can apply anytime here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

A quick reality check: what “losing priority” looks like when it hurts

Let’s make this real.

You file something early, but it’s broad and light. You then pitch a detailed deck that explains the real method. You share it with many investors. A few months later, someone else files a patent application that looks uncomfortably close to what you built. You finally file your real application with the detailed method.

Now you’re in a fight you didn’t plan for. Not a public fight, but a quiet one with lawyers, budgets, delays, and investor questions.

Even if you are the true inventor, your position can be weaker if your early filing doesn’t support your later claims, or if your public disclosure created prior art against you in key markets.

This is why priority is not a minor legal detail. It’s leverage.

And leverage is what early-stage teams need most.

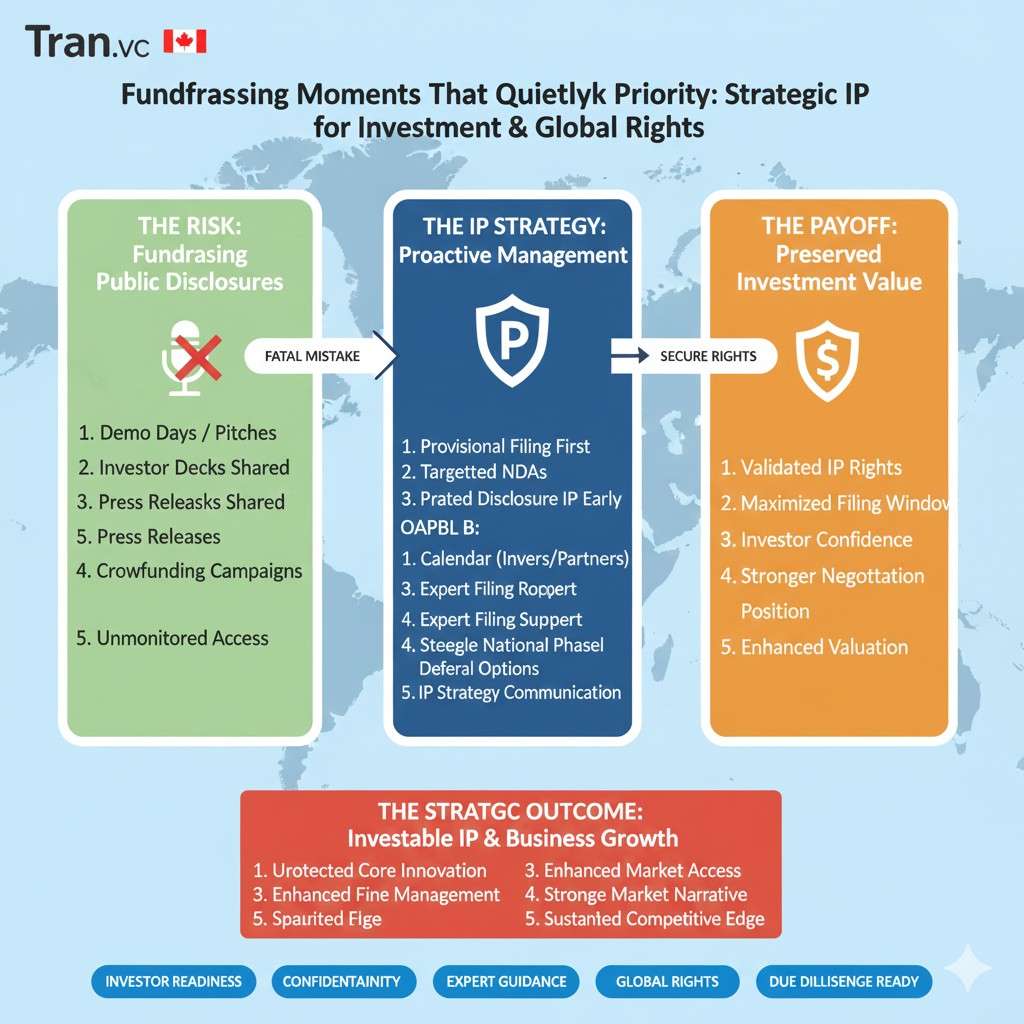

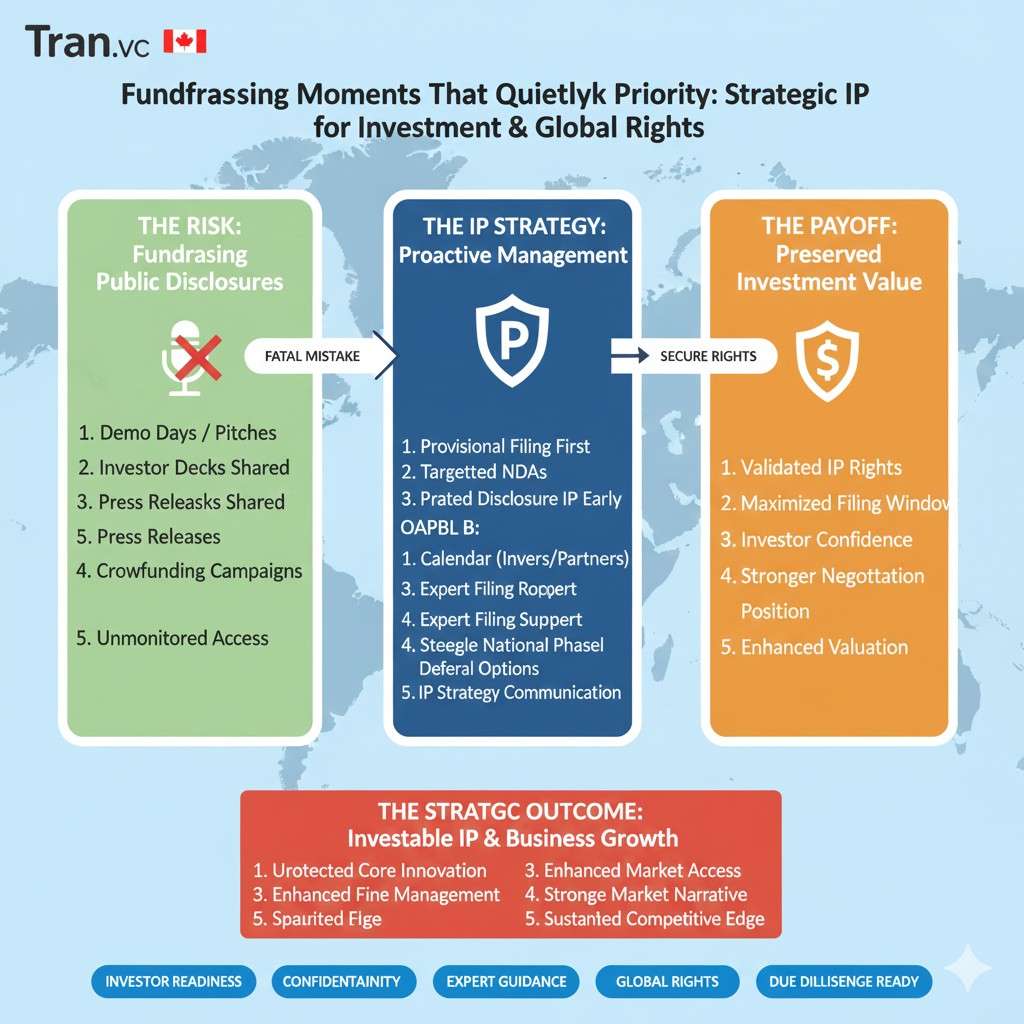

Fundraising Moments That Quietly Break Priority

The pitch deck trap

Your pitch deck is not “internal” just because you made it. The moment it leaves your laptop, it can become a disclosure. Many founders lose priority because they treat the deck like a safe place to explain the secret sauce. They add one slide that shows the full system flow, the training loop, the sensor stack, or the control logic. It feels normal, because investors want to understand why this will work.

The risk is not only that someone steals the idea. The bigger risk is that the deck becomes proof that the invention was already public before your filing covered it well. Even if the deck is shared under “confidential” language, it may still spread in ways you cannot track. Some investors forward decks to partners, advisors, or domain experts. Some add it to internal systems. Some print it. You lose control fast.

A safer way to pitch is to separate “what the product does” from “how the core method works.” You can show results, constraints, and why your approach is credible without giving away the steps that make it unique. If you need to explain the method to win the meeting, that is a strong sign you should file first, then share.

Investor calls and the “one more detail” habit

Many founders start strong, then slip near the end of the call. An investor asks, “Okay, but what’s the trick?” The founder wants to be helpful. They add the missing detail. Then the investor asks a follow-up. Then the founder adds the second missing detail. In ten minutes, the call becomes a technical walkthrough.

This usually happens because the founder is trying to build trust. They think, “If I explain it clearly, they will believe I can execute.” But you can build trust in other ways. You can talk about the problem, the constraints, the proof you have, and the roadmap. You can share the “why” and “what” without giving the full “how.”

If you know you tend to overshare when you get excited, plan for it. Write down three safe phrases you can use when the conversation pushes too deep. You do not need to sound defensive. You can say you are happy to share deeper detail after you lock filings, or under a more controlled process.

Data rooms and technical appendices

Data rooms feel formal, so founders assume they are safe. But data rooms are built for speed, not secrecy. A document can be downloaded, copied, or summarized. A screenshot can be taken in seconds. If your data room includes deep technical appendices, architecture diagrams, or training details, treat that as a disclosure risk.

A practical approach is to keep technical depth in layers. The first layer is high-level: market, team, traction, and results. The next layer adds product details that do not reveal the core method. The deepest layer is where the key invention lives, and that layer should be shared only when you have filing coverage and a clear reason to disclose.

If you want a simple rule, use this: if a page would help a skilled competitor rebuild your method, it should not be shared before a strong filing.

Demo days, pitch events, and recorded talks

Demo day is designed to be public. Even “closed” events can become public because talks are recorded, notes are shared, and slides are posted later. Founders often forget that a single diagram can reveal the key novelty. Robotics teams are especially exposed here, because videos show hardware, motion, timing, and interactions that can teach a lot.

Before any public talk, review your slides like a competitor would. Ask, “If I only saw these slides and heard this talk, could I rebuild the key method?” If the answer is yes, you should file first or remove the revealing parts.

If you already filed, still be careful. Your filing may not cover the new improvement you are about to show. Priority is not one date for everything. It is tied to what was actually disclosed in the filing.

Hiring and Team Growth Risks You Don’t Expect

Candidate interviews can become disclosures

When hiring, founders often share a lot to excite strong candidates. They show architecture, model design, roadmap, customer pilots, and technical challenges. Many candidates are currently employed at other companies. Some will interview with multiple startups. Even if they are honest, information travels in small ways.

You should treat hiring conversations as semi-public. That does not mean you act secretive. It means you choose what to share and when. You can describe the mission and the technical problems without giving away the specific solution that is patent-worthy.

A good habit is to prepare two versions of the technical story. The first version is safe for early interviews. The second version is deeper and used only when you are close to an offer, and ideally after you have filing coverage for the key invention.

Contractors, advisors, and “quick help” calls

Early teams often lean on contractors and advisors. Sometimes the help is informal: a friend reviews your approach, a professor gives feedback, an ex-colleague suggests a fix. These calls feel private. They are not always.

If you need outside help on the core method, set the ground first. Use a simple written agreement when possible. Keep notes of what you shared and when. Most important, file before you open the full hood if the method is truly novel and central.

Even when people act in good faith, confusion happens later. In patents, clear records matter. Priority fights are rarely about what you intended. They are about what can be proven.

Internal docs that leave the company

Not every disclosure is a blog post. Sometimes it is a Notion page. Or a shared Google Doc. Or a Slack export. Or a screenshot in a group chat. Teams move fast and forget that “share link” often means “anyone with the link.”

If your core method is written down in internal docs, lock access. Avoid open links. Use company accounts. Keep sensitive pages in a restricted space. This is not paranoia. It is basic hygiene.

This also helps later, because it creates a clean story of how the invention was handled before filing. Clean stories make diligence easier when you raise or sell.

Customer Pilots and Partnerships That Trigger Early Disclosure

The “we need to show it working” pressure

In B2B, pilots often decide your survival. Customers want proof. They want to see how it works. They ask questions. They want to know if you can integrate. They may ask for technical documentation and edge-case behavior.

Founders sometimes reveal the method because they think it will speed up the sale. But for many buyers, outcomes matter more than details. They care about reliability, cost, timelines, and support. You can often satisfy them without exposing your core invention.

If a customer truly needs to see the method, that is a sign the method is central to the business value. That is also a sign you should file first, then share with more comfort.

Statements of work, integration docs, and screenshots

Sales paperwork can contain technical detail. Statements of work sometimes include system architecture, data flows, security details, and performance metrics. Integration docs might show exactly how your pipeline works, what inputs you use, and what you compute.

Treat these documents as disclosures. Keep them at the right level. Write them so they explain what the customer needs to use the product, not how the secret engine runs inside.

If you must include deeper detail, do it after filing coverage, and make sure the contract has clear confidentiality terms. Still, do not rely on the contract as your only protection.

Joint development and who owns what

Partnerships can create a different problem: ownership confusion. If you co-develop an improvement with a customer or partner, you need to be careful about who has rights. This can affect your ability to claim priority cleanly, and it can affect whether you can file at all without permission.

The safest approach is to set invention ownership terms early, before the work begins. Many founders delay this because it feels awkward. But it is far more awkward later when you realize the best improvement was built inside a messy agreement.

If your business relies on deep tech moats, you want a clear path: you invent, you file, you own, you license if needed. Anything else can reduce your leverage.

Open Source, Papers, and Benchmarks in AI and Robotics

GitHub makes disclosures fast and permanent

Founders love open source because it helps hiring, credibility, and adoption. But GitHub commits can become prior art. A README can teach the method. A config file can reveal training details. An issues thread can explain why a design choice matters.

If you plan to open source any part of your system, decide what is truly moat-worthy and what is not. Keep the moat pieces protected first. You can still contribute to the community, but you do it with a plan.

It helps to think in parts. Some parts are safe to share: tooling, wrappers, deployment scripts, minor utilities. Some parts are core: novel data formation, novel training routines, novel control methods, novel safety constraints, novel sensor fusion logic. Those core parts should be filed before they are shared.

Papers and preprints are disclosures even when “early”

In AI, papers are a status symbol. They also attract talent and customers. The problem is that a paper is designed to teach. If it teaches your novel method before you file, you may lose rights in key markets and weaken your position even in markets with grace periods.

Preprints feel informal, but they are public. Once a preprint is out, the timestamp is out. If you later decide you want to patent, you may be stuck.

A strong strategy is to align publications with filings. File first, then publish. You can still be open, but you do it after you have locked your priority date for what matters.

Demos and benchmark posts can reveal more than you think

Benchmarks are tricky because they often require method detail to be credible. If you claim performance gains, people ask how. You might add a blog post that explains the training setup, the ablations, and the key design choices.

Sometimes the benchmark itself reveals the approach. In robotics, videos show timing, failure recovery, and sensing patterns. In AI, a model card can show data and architecture choices. Even small clues can be enough when combined.

If you want to share benchmarks safely, focus on outcomes and constraints. When you must share method detail, file first and make sure your filing includes the exact technique you are sharing, not an older version.

How to Build a “Priority-Safe” Habits Without Slowing Down

Treat filings like a product sprint, not a legal event

Most teams lose priority because filing is treated as a big, rare task. They wait until there is time. There is never time. Instead, treat filing like a sprint tied to product milestones.

When you hit a breakthrough, capture it quickly. When you plan a public moment, file before it. When you ship a major improvement, update coverage. This is not about filing every week. It is about keeping the IP timeline close to the build timeline.

This is where a partner like Tran.vc can change the game. You do not need to guess what to file and when. You get a plan, drafting support, and a founder-friendly process that matches the pace of startups. You can apply anytime here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Write like you are teaching a new engineer

A strong early filing is not marketing. It is teaching. The best mindset is: write it so a skilled engineer could build it, with reasonable effort, without calling you.

That forces you to include the real steps, the key choices, and the variations. It also forces you to avoid vague claims like “we optimize” or “we use AI.” Those phrases do not earn strong priority.

When founders do this well, they also learn something: they understand their own moat more clearly. That clarity helps fundraising, hiring, and strategy.

Keep a simple “before we share” check

You do not need a long checklist. You need a short pause before any public sharing. Ask yourself: are we revealing a new method, a new system, a new training process, a new control loop, or a new data approach that we have not filed?

If yes, pause and file or adjust the content. If you are unsure, assume it is risky. In priority, being conservative is cheaper than being sorry.

If you want help building this into your company rhythm, Tran.vc can support you with up to $50,000 in in-kind patent and IP services, designed for AI, robotics, and deep tech teams. Apply anytime: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/