Most founders hear “build a moat” and think it means speed, brand, or a bigger sales team. But in deep tech—AI, robotics, sensors, edge systems, novel hardware—investors also look for something quieter and harder to copy.

They look for proof that what you built is yours.

Not “yours” because you wrote the code first. Not “yours” because you posted a demo video. Not “yours” because you have a GitHub repo.

They mean “yours” in a way that holds up when a big company sees your traction and decides to clone you. Or when a competitor hires two engineers and rebuilds your key feature in six weeks. Or when a future buyer runs diligence and asks, very calmly, “So… what do you actually own?”

That’s what an IP moat is. It is not paperwork for later. It is not a trophy. It is not something you “get around to” after you raise.

It is a way to turn your technical edge into a real business edge.

And investors can tell the difference between founders who say they have a moat and founders who can show it.

At Tran.vc, we focus on helping technical teams build that kind of moat early—without wasting time, without burning cash, and without turning the process into a legal mess. If you’re building in AI, robotics, or other hard tech, and you want to protect what matters before you give away control, you can apply anytime here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Before we go deep, I want to make one thing clear.

A moat that investors respect is not just “having patents.”

It is having the right protection, for the right parts of your system, written in a way that matches how your product will evolve.

It is also having a plan that fits your stage.

Early-stage IP strategy should not feel like a big-company legal project. It should feel like good engineering: clean, intentional, and tied to real risk.

So in this guide, we will start from the ground truth: what investors really look for, what makes them trust an IP story, what mistakes quietly kill leverage, and how to build protection that grows with your product.

This article will be tactical. It will be simple. It will respect your time.

We’ll start with the first big idea: investors don’t respect IP that looks like a vanity move. They respect IP that reduces risk and increases leverage.

If that sounds obvious, good. Now let’s make it practical.

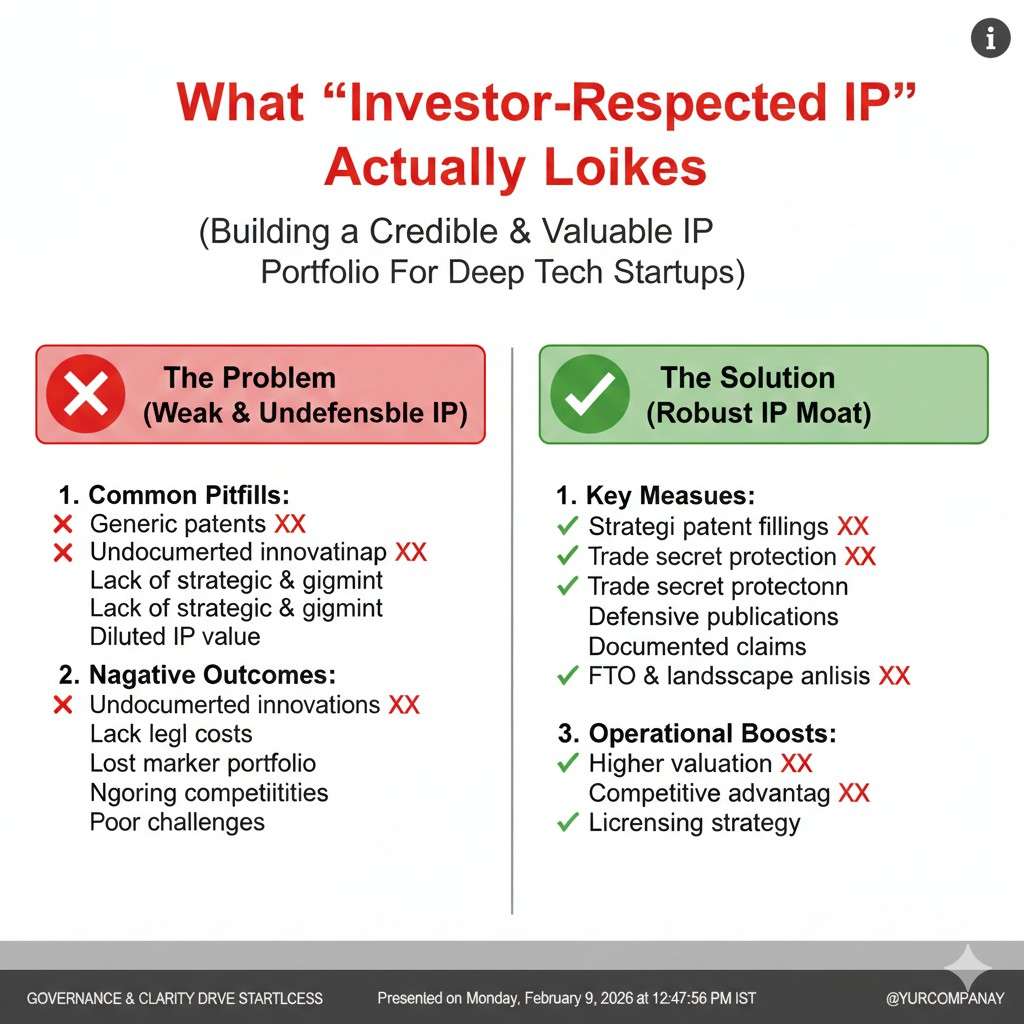

What “investor-respected IP” actually looks like

When an investor hears “we have a patent,” they do not automatically feel safer. Many have seen patents that protect nothing important. Many have seen filings that are too narrow, too broad, or aimed at the wrong thing. Many have seen founders spend a lot of money and still end up with weak coverage.

So what do they respect?

They respect IP when it does three things.

First, it protects the part of your system that creates real advantage.

Second, it matches a believable product roadmap.

Third, it creates leverage in fundraising, partnerships, and hiring.

That’s it.

And here is the twist: you can do all three even before you have product-market fit. You just need to stop thinking about IP like a “document” and start thinking about it like a system you design.

Let’s talk about that system.

If you build AI or robotics, your value usually lives in a small number of technical decisions that are hard to see from the outside. It might be the way your model adapts in the field. It might be how you fuse sensor data. It might be how you handle edge constraints. It might be a workflow that makes deployment safe and repeatable. It might be a calibration method. It might be a control loop that stays stable in messy settings. It might be a data engine that keeps improving without breaking.

Those are the kinds of things competitors want to copy.

But founders often file patents on the wrong layer. They file on the “feature.” They file on the “app.” They file on what’s easiest to describe.

Investors notice.

Because if your protection does not cover the hard part, then it is not a moat. It is a story.

A respected IP moat covers the hard part.

That means you need to know where your real edge lives. And you need language to describe it in a clean, structured way, without exposing trade secrets you should keep private.

That’s a skill. Like any skill, you can learn it.

Start with a blunt question: “What can a competitor copy in 90 days?”

This is the simplest way to find what matters.

Imagine you wake up tomorrow and a funded competitor decides to copy your product. They hire smart engineers. They read your docs, your papers, your job posts, your marketing, your code if it’s public, your demos, your patents if you have them. They run tests. They buy what you sell. They try to reproduce your output.

Now ask: what can they rebuild in 90 days?

Be honest.

A UI can be copied.

A dashboard can be copied.

A basic inference pipeline can be copied.

A standard model can be copied.

Even “we use LLMs” can be copied.

So where would they struggle?

They would struggle where you made choices that are not obvious. Where the system only works because of a specific chain of steps. Where the data is handled in a unique way. Where the edge cases are solved. Where the math works out. Where the hardware and software interplay is tuned.

That is where your moat starts.

And if you cannot answer this question clearly, an investor will worry that you don’t know what you’re selling.

This is why strong IP strategy is not just legal work. It is founder work. It forces clarity.

If you want help mapping your “copy risk” and converting it into a real IP plan, Tran.vc does that hands-on as part of our in-kind IP investment. You can apply anytime here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

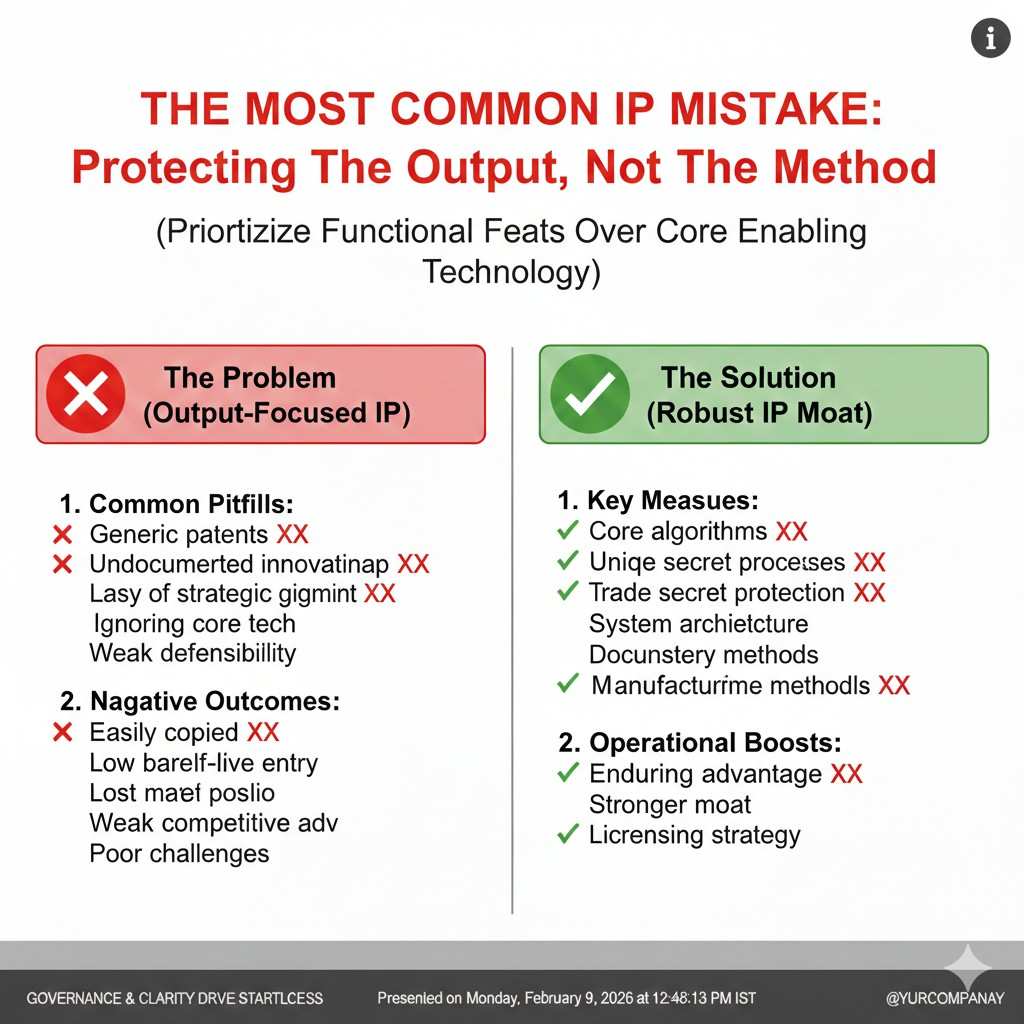

The most common IP mistake: protecting the output, not the method

In AI and robotics, many founders talk about what their system achieves. Higher accuracy. Faster planning. Better stability. Lower power use. More reliable autonomy. Fewer false alarms. Less drift. Better grasping.

These outcomes matter. But outcomes are not usually what you can protect.

You protect the method.

And not just a single method. You protect a method family. You protect the parts that will still be true a year from now when you ship v3 and your competitor finally tries to catch up.

A respected moat is not fragile. It does not break the moment you refactor.

So instead of writing a patent around “we detect defects using a neural network,” you protect the specific way you do it. The chain of steps. The system constraints. The training data handling. The domain adaptation trick. The uncertainty gating. The feedback loop. The calibration.

Same for robotics. Don’t protect “a robot that picks objects.” Protect the method that makes your pick succeed in ugly, real-world lighting with occlusion and random packaging, while keeping cycle time low.

This is why “simple IP” often fails. It describes what everyone does. The examiner has seen it. Your competitor has seen it. An investor has seen it.

If you want investors to respect your moat, you must protect what is special, not what is common.

Another mistake: filing too early with a fuzzy invention

You can file early and still be smart. But “early” does not mean “before you know what the invention is.”

Some teams rush to file as soon as they have a concept. They write broad claims that try to cover everything. They submit a thin description with gaps. They treat it like a placeholder and tell themselves they’ll fix it later.

Investors are not impressed by that. They know what it looks like when a filing is not rooted in reality.

What you want is a filing that is early and specific.

Specific does not mean narrow. It means grounded.

It means the document shows you understand your system deeply. It shows you can explain how it works. It shows you have identified the point of novelty. It shows multiple variations so it can grow.

That’s what “defensible” looks like.

When you do it right, a filing becomes a blueprint for your moat. It becomes part of your fundraising story. It becomes a tool for diligence. It becomes a reason a big company takes you seriously.

When you do it wrong, it becomes a cost and a false sense of safety.

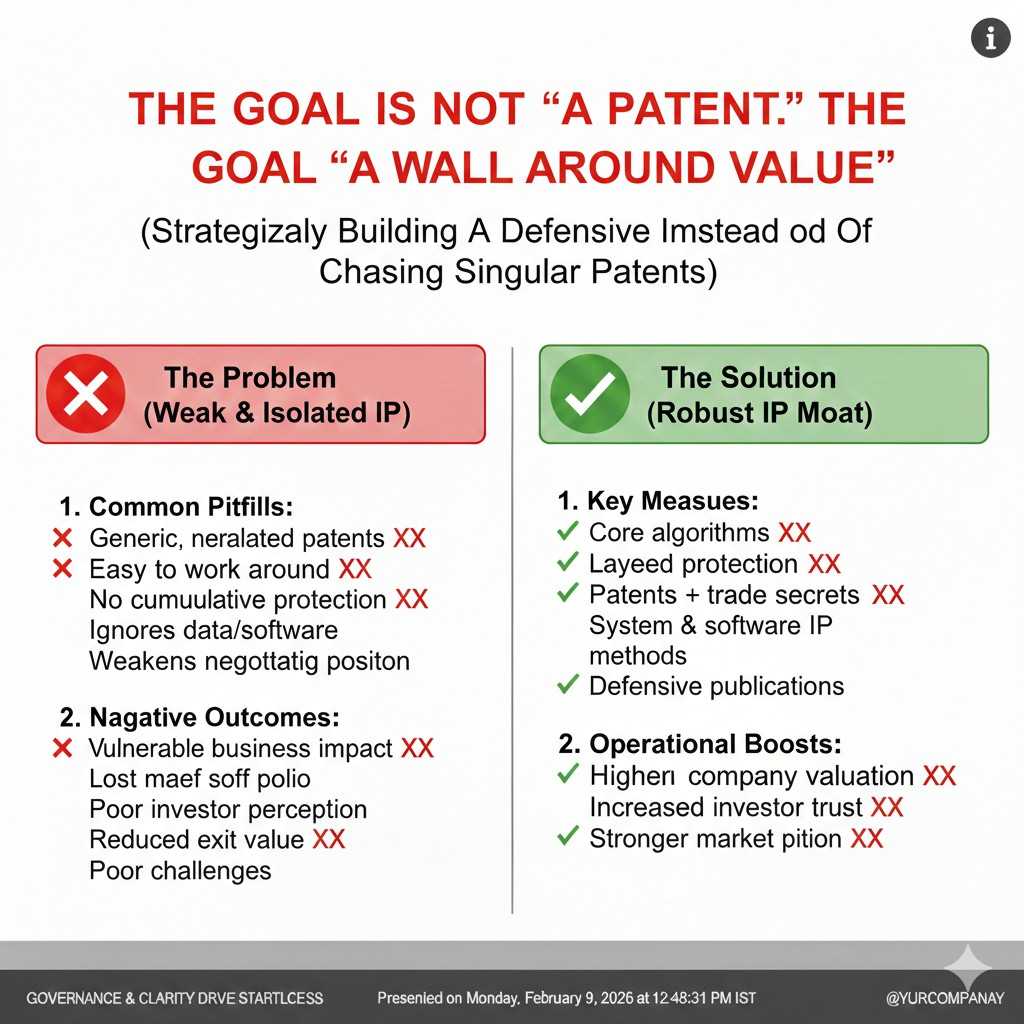

The goal is not “a patent.” The goal is “a wall around value.”

Let’s make this concrete.

If you build a platform for warehouse robotics, your value might not be “a robot.” The robot body can be bought. The cameras can be bought. The motors can be bought. A lot of it is commodity.

Your value might be:

- a planning approach that deals with mixed traffic,

- a perception stack that stays reliable when dust appears,

- a safety method that allows higher speed while staying compliant,

- a fleet learning loop that reduces failures every week,

- a calibration method that cuts install time from days to hours.

If you protect the robot itself, you missed the point.

You need a wall around the method that makes the system work at scale.

That wall can include patents, yes. But it can also include trade secrets, clean internal documentation, invention capture habits, and a filing roadmap that grows with your releases.

A respected moat is layered.

Investors are not looking for a single magic patent. They are looking for a pattern that says: “This team protects what matters.”

The “IP moat” is also a behavior pattern

Here’s something founders don’t hear enough.

Investors don’t only judge the IP you have today. They also judge whether you will keep building protection as you build the product.

They want to see that you are an organized team. That you track inventions. That you understand open source risk. That you handle contractor work cleanly. That you have signed assignments. That your code and data are not a legal landmine.

Because in deep tech, diligence gets real. Buyers and later-stage investors ask hard questions.

If your answer is “we’ll deal with it later,” you lose trust.

But if your answer is calm and structured—“we have a process; here is what we filed; here is what we plan; here is what we keep as secrets; here is how we avoid leaks”—you gain trust.

This is part of why Tran.vc exists. We help teams set up the process early so IP becomes a strength, not a scramble. If you’re building something technical and you want to raise with leverage, you can apply anytime here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

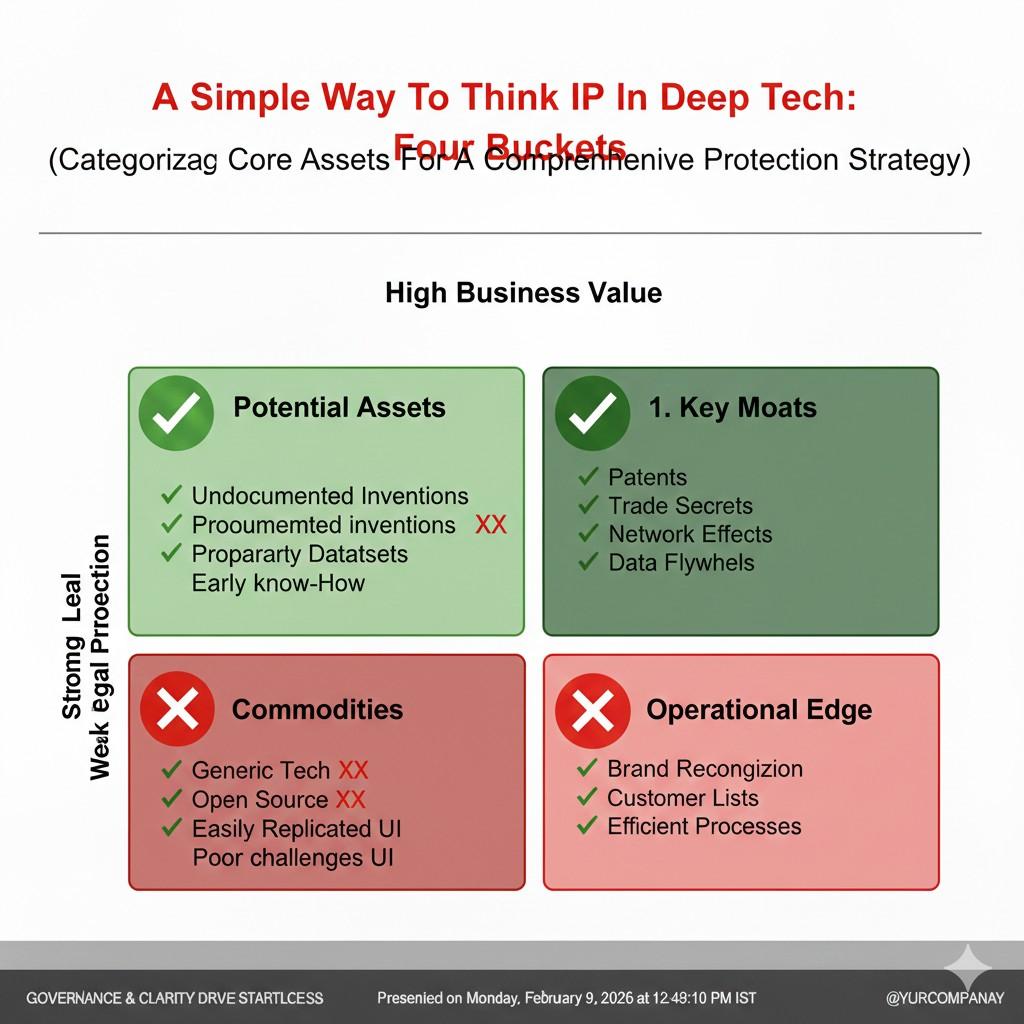

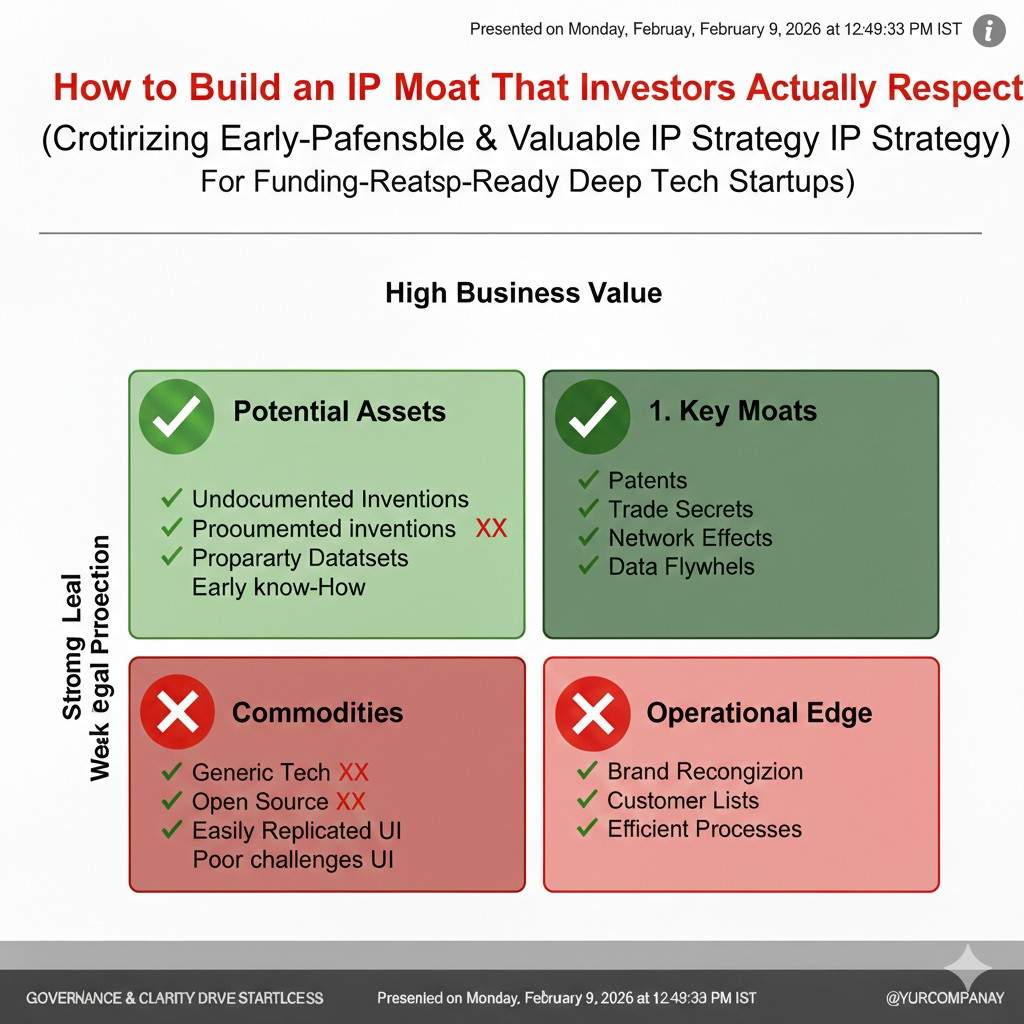

A simple way to think about IP in deep tech: four buckets

I will keep this minimal.

Most investor-respected IP in AI and robotics falls into a few buckets:

- Core method: the technical approach that makes your system perform better or cheaper or safer.

- System design: how components interact in a way that creates stability, speed, reliability, or scale.

- Data engine: how you collect, clean, label, learn, and improve over time.

- Deployment and operations: how you install, monitor, update, and keep performance steady in real environments.

A lot of founders only think about bucket 1. Investors respect founders who protect across multiple buckets—because it shows you are building a business, not just a model.

But you don’t need to do everything at once. You need to start with the highest-leverage bucket for your product today.

So what happens next?

In the next section, we’ll get into the step-by-step approach to building an IP moat that investors actually respect.

We’ll cover:

- how to find the “one or two” inventions that matter most right now,

- how to capture them without slowing your engineering team,

- how to decide what to patent and what to keep secret,

- how to talk about your moat in a pitch without sounding vague or salesy,

- and how to build a filing roadmap that matches your next 12 months.

How to Build an IP Moat That Investors Actually Respect

Why investors say “moat” but mean “ownership”

When investors use the word “moat,” they are not talking about your energy, your pitch, or your vision. They are trying to measure risk. They want to know what happens if someone bigger notices you and tries to copy what you built.

In AI and robotics, copying is not a rare event. It is normal. If the market is real and the pain is clear, someone will try to rebuild your product. Investors respect IP when it turns that threat into a problem for the copycat, not for you.

A strong moat is proof that you own the hard part. Not just the output your system shows on a demo day, but the method that makes that output reliable in the real world.

What “respect” looks like in an investor’s head

Investors do not clap because you say “we filed a patent.” They look for signs that you can protect value with intent, not by luck. They respect IP when it is tied to your real edge, written in a way that can survive product changes, and backed by a clear plan.

That plan matters because early startups change fast. If your protection breaks the moment you update your model or refactor your pipeline, it will not feel real. A respected IP moat grows as you ship, and it does not force your team to freeze the product.

If you want help building that kind of plan early, Tran.vc works hands-on and invests up to $50,000 in in-kind patent and IP services for deep tech teams. You can apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

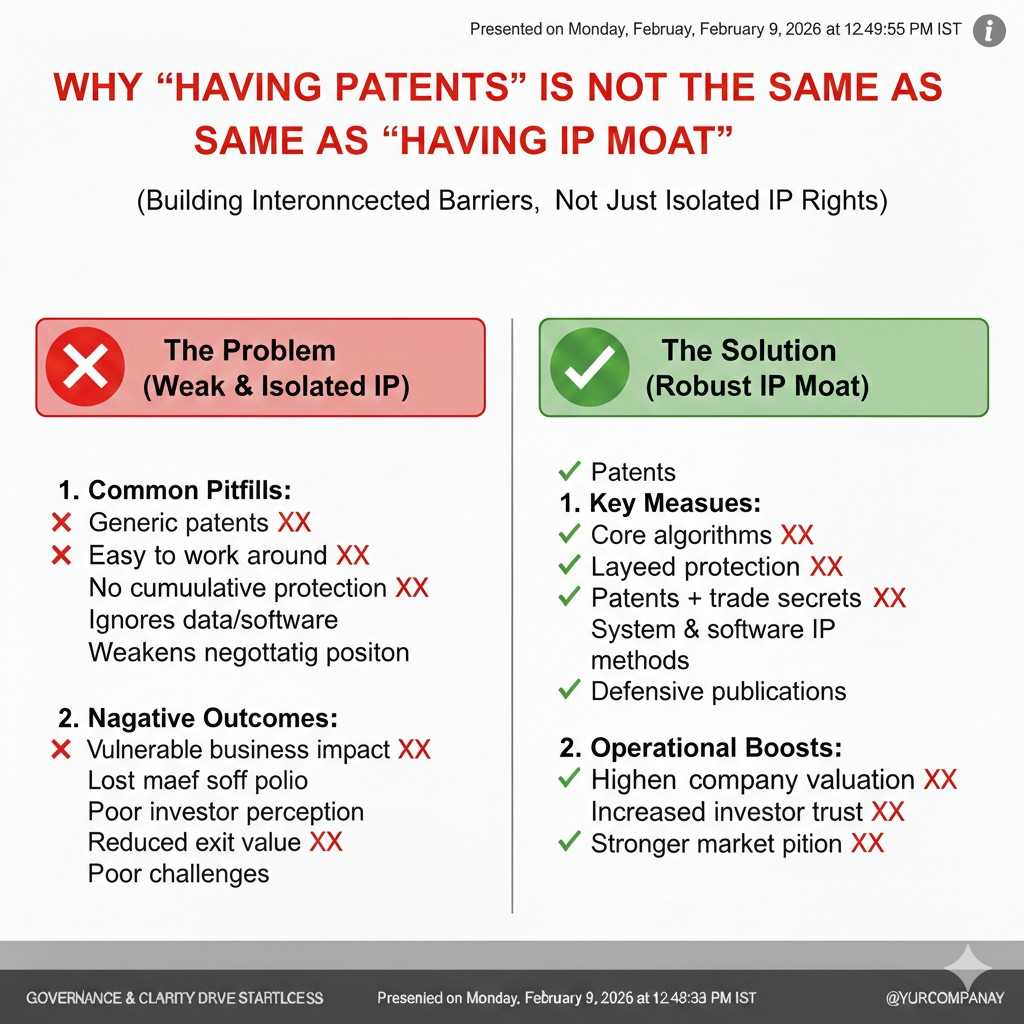

Why “having patents” is not the same as “having a moat”

Many patents are not useful. Some are too narrow and can be avoided with small changes. Others are too broad and get rejected or watered down. Some protect a feature that is easy to copy, while the real advantage sits elsewhere.

Investors have seen all of this. That is why they look past the count and ask deeper questions, like what the patent covers, what problem it blocks, and whether the filing matches how your product will actually be built and sold.

A moat is not a number. It is a wall around value.

Find the real edge before you protect anything

Ask the blunt question: “What can a smart team copy in 90 days?”

The fastest way to find your real edge is to imagine a real threat. Picture a well-funded team that wants to copy you. They can hire good engineers. They can buy your product. They can watch your demos. They can read your docs. They can rebuild your UI and flows quickly.

Now ask what they can copy in 90 days, and what will still be hard after 90 days. This exercise forces you to separate surface-level work from deep advantage. Investors do this in their heads even when they do not say it out loud.

If the answer is “they can copy most of it,” that does not mean you are doomed. It means your moat is not yet clear. Your job is to locate the part of your system that is truly hard to recreate, then protect that part with focus.

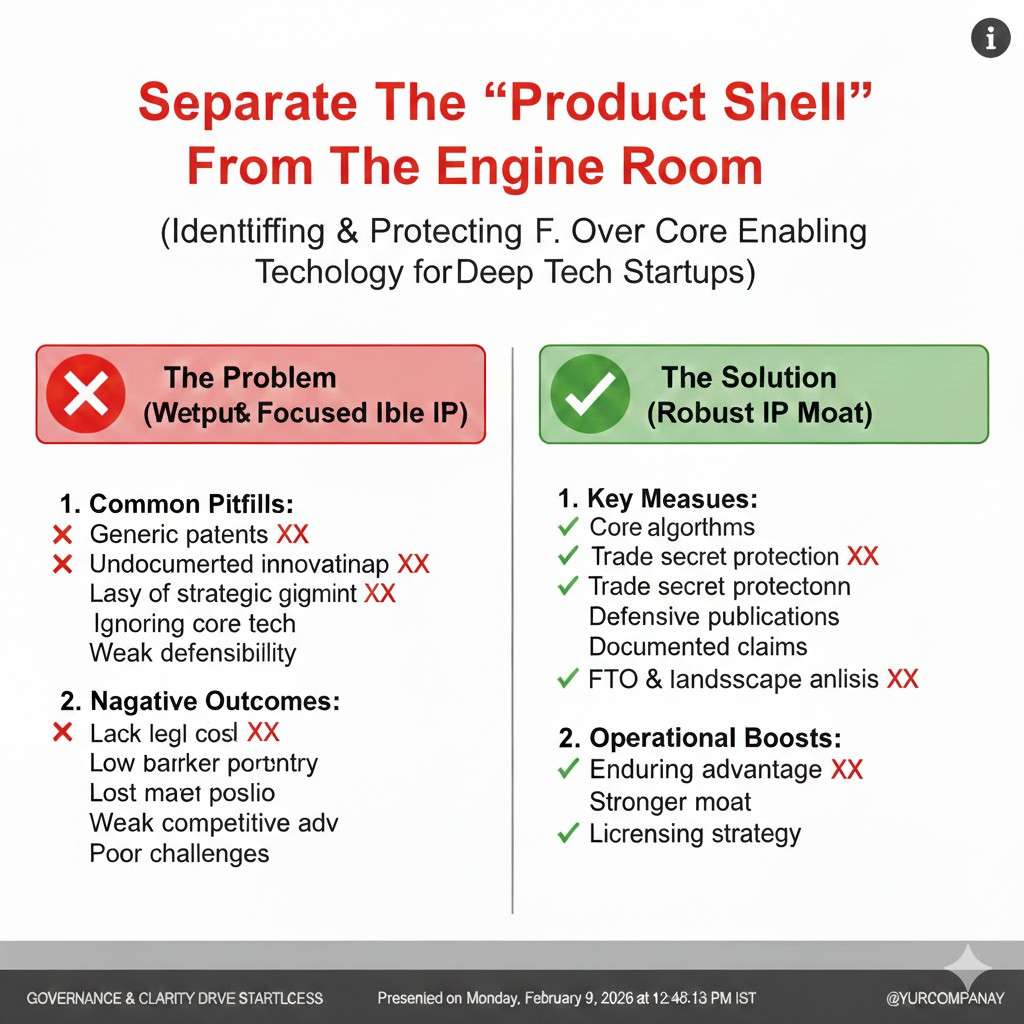

Separate the “product shell” from the “engine room”

In deep tech, the shell is often the visible layer. It is the interface, the dashboard, the alerts, the reports, the user steps, the model choice, and the standard pipeline. A competitor can copy this by watching you for a week.

The engine room is where your real value often lives. It is the method that makes the system stable, safe, accurate, or cheap. It is the series of choices that create reliability under messy conditions. It is also the set of tradeoffs you learned through testing that are not obvious to outsiders.

When you protect the shell, you get weak IP. When you protect the engine room, you start building a moat investors respect.

Name your advantage in plain words

Founders often describe their edge in complex language. They do it because the work is complex, and because they want to sound advanced. But investors do not reward complexity. They reward clarity.

A useful exercise is to write your edge in a simple sentence that a smart non-expert can understand. Then write the same idea again in one paragraph, with enough detail to show it is real. This is not marketing. This is a test of whether you truly know what is special.

If you can’t say it plainly, it is hard to protect, hard to pitch, and hard to defend.

Protect the method, not the outcome

Why outcomes are easy to copy

It is tempting to focus on results. Better accuracy. Faster planning. Lower power use. Better grasp success. Fewer failures. These outcomes matter, but they are not always protectable on their own.

A competitor does not need your exact system to chase your outcome. They can use a different approach to reach similar results. That is why an investor is less impressed by “we do X better” and more impressed by “here is the method that makes our system work under these constraints.”

To build a moat, you protect the method family, not only the scoreboard.

What a “method family” means in practice

A method family is a group of related ways to solve the same core problem. Instead of writing protection that only matches one version of your product, you describe the core steps and show variations.

For example, if your advantage is a way to adapt a model in the field without breaking safety limits, you don’t want protection that depends on one model type or one data format. You want protection that covers the logic, the flow, the gating rules, the update method, and the safety checks, with multiple options.

Investors respect this because it looks like engineering maturity. It shows you know your product will change, and you are protecting the part that stays true.

Don’t expose secrets while still filing strong IP

A common fear is that filing a patent forces you to reveal everything. In practice, good strategy balances patents and trade secrets. You disclose enough to support strong protection, but you do not give away the “extra edge” that is better kept internal.

This is where experienced guidance matters. The goal is not to publish your playbook. The goal is to block copycats from using the same core method, while keeping key details private when that gives you more long-term advantage.

Tran.vc helps teams decide what to patent and what to keep secret in a way that fits how deep tech products evolve. If you want that kind of support, apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

File early, but don’t file vague

The real risk of “we’ll fix it later”

Some teams file too early with fuzzy descriptions. They treat the first filing like a placeholder, assuming they can clean it up later. But weak early filings often become anchors. They shape what you can claim later, and they can limit you when you try to expand.

Investors can also sense when a filing is thin. If the document reads like a generic idea and not like a real system, it does not build confidence. It can even create doubt about whether the team understands its own edge.

Filing early is good only when early also means grounded and specific.

What “specific” looks like without becoming narrow

Specific does not mean you lock yourself into one design. It means your filing shows real structure. It explains the problem clearly, explains why known methods fail, and then explains your method with steps that can be tested and implemented.

A strong filing also includes variations and alternative flows. That is how you stay broad while staying real. It is like designing an API that can support new features later. You define the core logic, then show paths that still count as your invention.

This is why investors respect well-built IP. It looks like it was created by people who ship.

Match the filing to your roadmap

Your product today is not your product in twelve months. Investors know this. They want to see protection that maps to what you plan to build next, not only what is in the prototype.

A good approach is to treat IP like a roadmap that runs alongside your product roadmap. As you reach milestones, you capture inventions that appear in those milestones. This keeps you from filing random ideas and keeps you focused on protecting what will matter when revenue and partnerships show up.

Build a layered moat, not a single wall

Patents are one layer, not the whole story

Patents can be powerful, but investors respect them most when they sit inside a larger system. That system includes trade secrets, clean invention capture, proper assignments, and strong internal habits that prevent leaks.

Think of patents as a public fence that blocks certain paths. Then think of trade secrets as the locked doors inside the building. If someone gets past the fence, they still can’t run your business without the parts you kept private.

This layered view is practical. It also signals maturity in diligence.

Use trade secrets on the parts that are hard to reverse engineer

Some parts of your advantage are best kept private. This is often true when the method is difficult to see from the outside, and when the advantage comes from small tuning decisions, data handling tricks, or operational rules.

If a competitor can’t easily observe it, keeping it as a trade secret can be stronger than publishing it in a patent. But trade secrets only work if you treat them like assets. That means access control, clean documentation, and clear ownership with your team.

Investors respect this because it shows you are not giving away your edge for free.

Keep your open-source and contractor work clean

Many startups accidentally weaken their IP through messy foundations. They use open-source code without tracking licenses. They hire contractors without clear invention assignment terms. They let contributors commit code without proper agreements.

This becomes a problem later in fundraising and acquisitions. It can also become a problem if someone claims ownership of what you built. A respected IP moat includes clean paperwork and clean practices from the start.

This is not about being paranoid. It is about avoiding preventable risk.

Turn your IP moat into fundraising leverage

How investors actually use IP when deciding to invest

Investors use IP as a signal. It tells them whether you can protect future returns. It also tells them whether you understand your market and your competitive threats.

If your IP protects the wrong thing, it signals weak thinking. If your IP protects the right thing and aligns with your roadmap, it signals strong thinking. That changes the tone of a meeting.

It can also change your valuation discussions, because risk feels lower and your upside feels more defensible.

Talk about IP without sounding like a legal brochure

Founders often swing between two bad extremes. They either avoid IP completely, or they drown the investor in legal terms. Neither approach builds confidence.

A better approach is to describe IP as part of your business design. You explain what the hard part is, why it matters, and what you did to protect it. You keep the language simple, and you tie it to real competitive scenarios.

If you can say, “This method is hard to copy, and our filings block the most likely copy paths,” you will sound credible without sounding like you are hiding behind paperwork.

Show a plan, not just a filing

Investors like to see that you have an IP plan that keeps moving. One filing can be luck. A plan suggests repeatability.

This does not mean you need a giant portfolio early. It means you can explain what you protected, what you will protect next, and how that maps to releases, pilots, and production deployments.

That story is often more persuasive than a stack of documents.

If you want Tran.vc to help you build this kind of IP story and filing path while investing up to $50,000 in in-kind IP services, you can apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/