Picking countries for patent filing can feel like trying to play chess in the dark. Founders hear advice like “File in the US and Europe” or “Just do PCT and decide later.” But none of that tells you how to choose the right places for your product, your buyers, and your budget.

The good news is you do not have to guess. You can make this choice like an engineer: start with facts, run simple checks, and follow a clear path.

Tran.vc helps technical founders do this early, before money gets tight and before a competitor copies the core idea. If you want support building an IP plan that fits your real go-to-market plan, you can apply anytime here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

The real question is not “Where can we file?”

It is: Where will this patent protect revenue or reduce risk?

A patent is not a trophy. It is a tool. It is there to:

- make it harder for others to copy your core product

- give investors comfort that you are not easy to clone

- help you win deals when big customers ask, “What stops others from doing this?”

- give you leverage if a larger company steps on your toes

So the “right” countries are the countries that help those goals. Nothing else.

If you remember one rule, make it this:

File where you will sell, where others will build, and where enforcement matters.

Now we’ll break that into a simple method you can use with a spreadsheet and one honest meeting with your team.

Step one: map your business to the world in plain terms

Most founders start with legal maps. That is backwards. Start with business maps.

Ask three simple questions.

1) Where will the money come from in the next 3 years?

Not “someday.” Not “global.” Real money. Real buyers.

If you sell to factories, warehouses, hospitals, energy plants, or defense, the money is usually concentrated in a few places. If you sell software, it may spread wider, but even then it often clusters.

Write down your best guess for the next 36 months:

- the top 10 target customers (or customer types)

- where they are located

- where purchasing decisions happen

Many teams miss the last part. A product may be used in one country but bought from another.

Example: you may deploy robots in Singapore, but the buyer and legal contract might sit in the US or Japan. For patents, the buyer location can matter more than the deployment location, because that is where deal pressure and partner pressure show up.

2) Where will competitors copy from?

Copying often happens where engineering talent is strong and manufacturing is dense.

For robotics and hardware, this matters a lot. Many teams sell in one place, but parts are built in another place.

So ask:

- where can someone produce a similar product fast?

- where are the suppliers?

- where do competitors already build?

If a competitor can manufacture in a country where you have no protection, they can ship into your market in ways that make your life hard.

This is why “where you sell” is only half the story.

3) Where does your tech get made?

For AI, the “made” part can mean where models are trained, where code is written, or where the system is deployed.

For robotics, “made” often means where:

- key parts are manufactured

- final assembly happens

- calibration and installation happens

Patents can matter in these places because patent rules often focus on “making,” “using,” “selling,” and “importing.” If your patent coverage misses the “making” location, you may lose a big chunk of leverage.

Step two: understand the four “country buckets” that matter

Now we turn the business map into filing choices. Most countries you might file in fall into four buckets. You do not need a huge list. You need a few strong picks.

Bucket A: your core revenue markets

These are places where:

- your best customers are

- deal sizes are large

- buyers care about risk and prefer protected vendors

If you sell to enterprise or government, patents can directly help procurement. Buyers may not say it out loud, but many prefer vendors that look “real,” and patents are one sign.

In many deep tech cases, this bucket includes the US. Often it includes one or two others based on your industry.

Bucket B: the strongest competitor markets

These are places where your biggest rivals are based or where they sell heavily. If you have protection there, you can:

- slow them down

- push them into design changes

- create negotiation power

Sometimes you do not sell much in that place today. That is fine. The point is leverage.

Bucket C: manufacturing and supply chain hubs

If someone can manufacture your core system in a hub and ship it worldwide, protection in that hub can be a pressure point.

This is very common in robotics, sensors, devices, and embedded AI.

Even if you never open an office there, filing there can still be worth it.

Bucket D: partnership and exit magnets

These are places where likely acquirers are, or where your biggest strategic partners live.

If your top “future buyer” is a Japanese company, filing in Japan might matter even if you do not sell there right away. It can make your company look safer to buy and easier to value.

This bucket is not about ego. It is about “What will matter in a boardroom during an acquisition or a big partnership?”

Step three: score countries using a simple, honest system

Here is a system founders can use without law school.

Pick 8–12 countries you are thinking about. Then score each one from 0 to 3 on each factor below:

- Revenue in 36 months

- Competitor threat

- Manufacturing risk

- Partnership / exit value

- Enforcement practicality (we’ll explain this)

- Budget fit

Add the score. The top 2–5 are usually your answer.

You do not need to be perfect. You need to be consistent.

The factor most founders ignore: enforcement practicality

A patent is only as useful as your ability to use it.

Enforcement practicality means:

- Is it realistic to enforce there if needed?

- Are courts and processes workable?

- Is it common for businesses to respect patents there?

- Would a competitor care if you had a patent there?

You do not need to become an expert. You just need to avoid places where a patent will be hard to use and easy to ignore, unless you have a very strong reason.

This is also where cost matters. Some places are expensive not only to file, but to maintain and enforce.

At Tran.vc, a big part of the work is helping founders pick the countries where patents actually create leverage, not just paper.

You can apply anytime if you want help building this plan around your real market: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Step four: decide what “coverage” really means for your product

A common mistake is thinking a patent is one thing. It is not. A patent can protect different parts of your system, and that changes where you should file.

Let’s make this concrete.

If your moat is an algorithm

If your key value is a method that runs in software, then the important countries are often where:

- your customers are

- your competitors sell

- cloud and software businesses operate

But you must also be careful: some countries have stricter rules about software patents. You can still protect many AI ideas, but the way you write and frame them matters. You may focus on the technical system, the data flow, and the real-world result, not vague math.

So if your moat is software-like, your filing plan might lean toward major commercial markets and competitor markets.

If your moat is a robotic mechanism or sensor design

Then manufacturing and import routes matter more. You may need protection where parts are made, where assembly happens, and where products enter your key markets.

Because if someone can build it in a manufacturing hub and ship it into your customer market, you want to stop the product at the border or pressure them before they scale.

If your moat is “system + process”

Many robotics and AI startups win because of a full stack: hardware, control, training, calibration, deployment.

In that case, you want patents that cover the system as a whole, plus the most copyable sub-parts. That can let you file in fewer places but still block copycats.

This is a big theme in seed-stage IP: you do not file everywhere. You file smart.

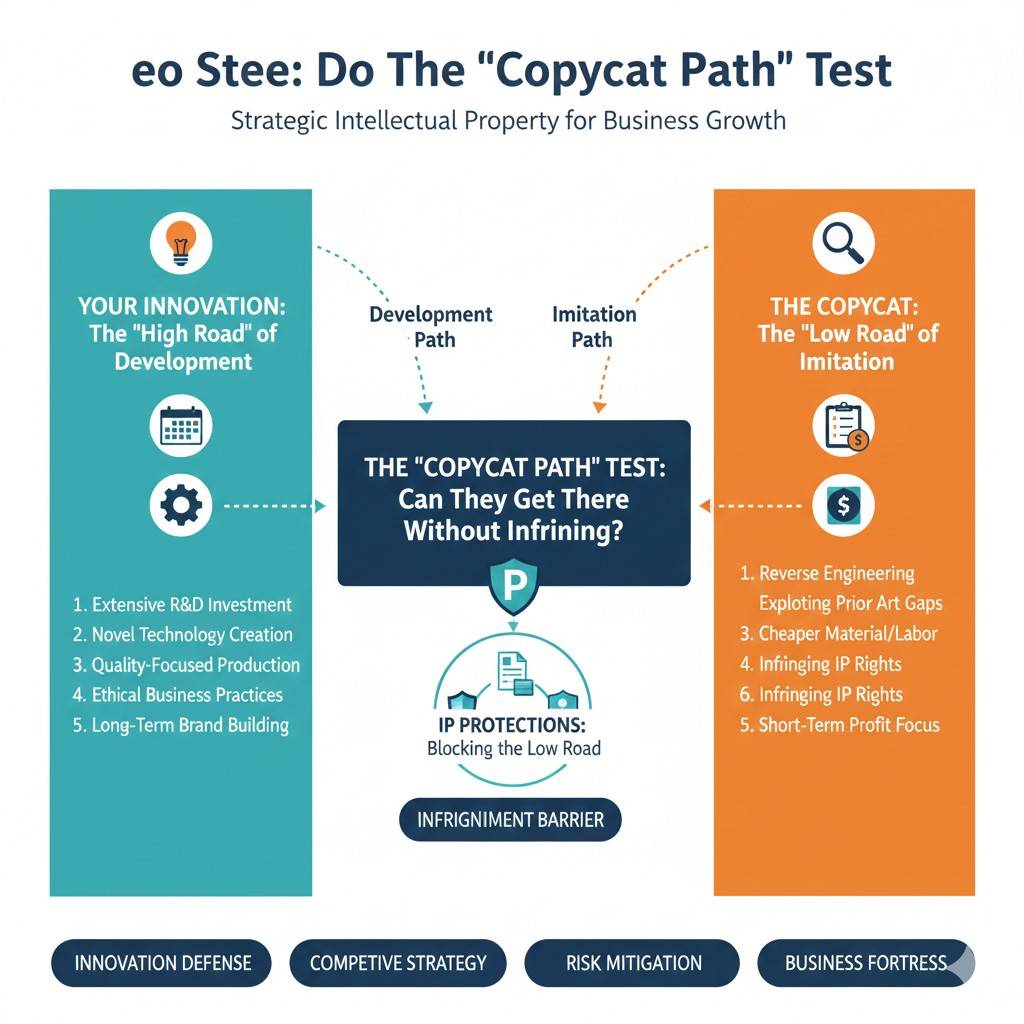

Step five: do the “copycat path” test

Here is a fast test that works well for early teams.

Imagine a well-funded competitor wants to copy you in 12 months. They will do three things:

- build a similar product

- sell it to your target customers

- raise money by claiming they do what you do

Now ask: What path would they take?

- Where would they build it?

- Where would they sell it first?

- Where would they show traction?

- Which partners would they use?

Your patent country picks should block or slow that path.

If your plan covers only where you sell today, but not where they build, they may still move fast. If your plan covers only where they build, but not where customers buy, you may not have deal leverage.

The best plan creates pressure at more than one point in the path.

Step six: avoid the “country shopping” trap

Some founders collect countries like stamps. It is a costly trap.

A bigger country list is not always better. Every country you add means:

- filing costs

- translation costs in many places

- ongoing fees every year

- more complexity during fundraising and diligence

It is often better to file in fewer places but write a stronger set of claims that cover the right angles.

The goal is not “max countries.” The goal is max leverage per dollar.

Tran.vc is built around this idea. Instead of pushing founders into expensive, scattered filings, the focus is on building an IP base that makes the company harder to copy and easier to fund. If you want to explore that, apply here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

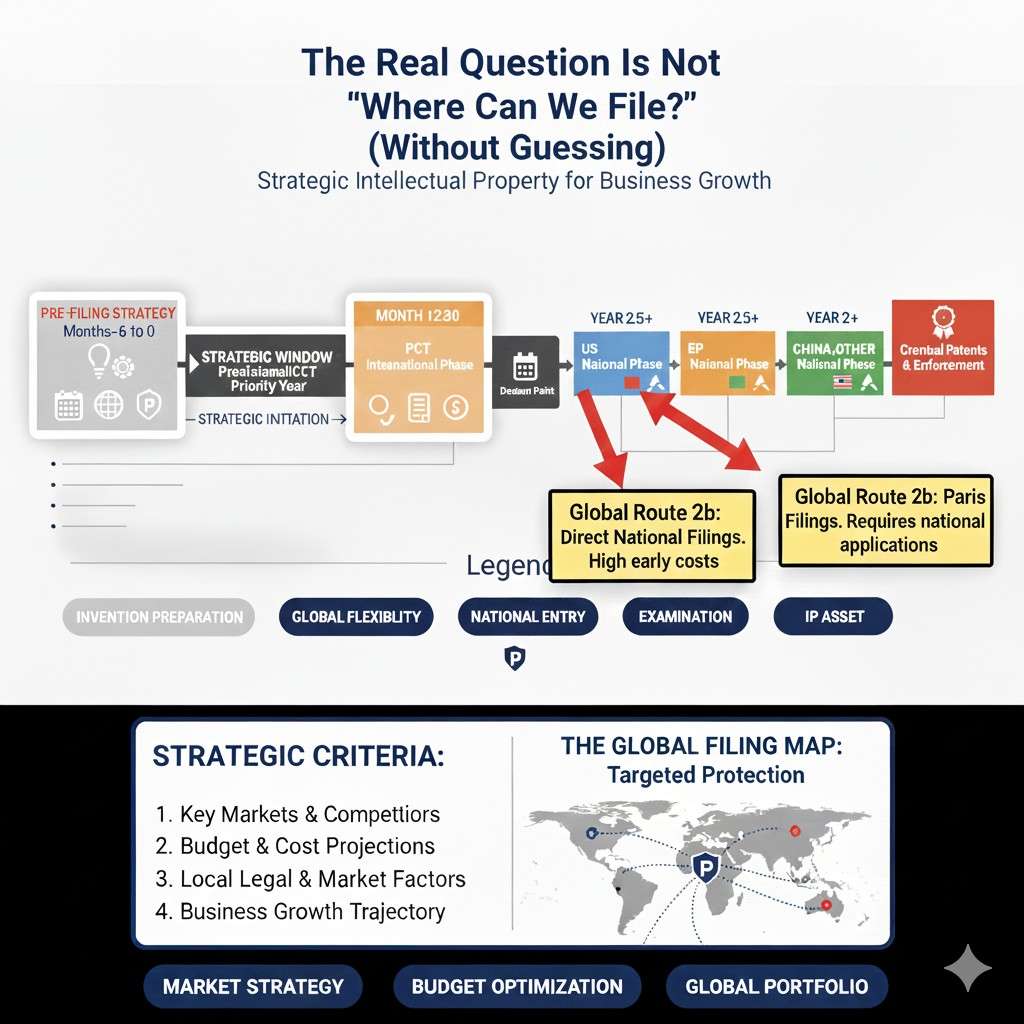

Step seven: use timing to keep options open without wasting money

This part matters a lot for pre-seed and seed.

You do not need to pay for everything today. But you do need to protect your earliest filing date, because that is what sets your priority.

A common, sensible path looks like this:

- file a strong first application that captures the core invention and key variants

- then use that first filing date to keep your place in line while you learn more about markets

- then pick countries later when you have better customer data

This is where founders use international pathways. The point is not the paperwork. The point is buying time to learn without losing your spot.

But be careful: “We’ll decide later” only works if the first filing is strong. A weak first filing locks you into weak protection everywhere.

Step eight: make the decision investor-proof

Even if you never sue anyone, patents still matter in fundraising. Investors often ask:

- What is defensible here?

- What is the moat?

- Can a big company copy it?

- Are there patents?

- Are you filing in the right places?

When you can answer, calmly and clearly:

“We picked these countries because they match our first revenue markets, our competitor risk, and where manufacturing happens. We did not waste money filing in places that do not change our risk.”

…you sound like a founder who understands strategy, not just tech.

That helps.

A practical example (simple, not perfect)

Let’s say you are building an AI vision system for warehouse robots.

- Your first customers are US logistics firms.

- Competitors are in the US and Europe.

- Some hardware is made in Asia.

- A likely partner is a Japanese automation company.

A smart early plan might focus on:

- the US for customers and fundraising

- one key European route if competitors and buyers are there

- one manufacturing hub if the core hardware is easy to copy there

- Japan if partnership value is real

That could be 2–4 places, not 15.

And you might keep options open for more later, once you know where sales land.

This is the kind of plan Tran.vc helps founders build early, so every IP dollar has a reason. Apply anytime: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Step one: map your business to the world in plain terms

Start with where the money will land

Before you think about laws or forms, think about cash. A patent plan should follow the path of money, because money is what you are protecting. If you are not sure where the money will come from yet, that is okay. You can still make a smart first call by looking at where the first real buyers in your space usually live.

Look at your next 36 months, not your dream timeline. Write down the industries you are selling into and the kinds of companies that buy tools like yours. Then look at where those companies spend most of their budgets. For many robotics and AI startups, a large share of early spend tends to cluster in a few markets, even if the product could be used everywhere.

Separate “use location” from “buy location”

A common mistake is thinking the country where your product is used is the same as the country where it is bought. In B2B, that is often not true. A robot may run in one place, but the deal may be signed in a different place, and the legal and payment team may sit somewhere else.

When you choose patent countries, the “buy location” can matter more than the “use location.” That is where contract pressure lives. That is where buyers ask hard questions. That is where big partners want to see you are protected.

Don’t guess the market, confirm it using proof

Even in early stage, you can gather proof fast. Look at where your inbound interest comes from, where your pilots are, and where your strongest advisors have networks. If you are building in a known category, also study where similar companies first found traction.

You do not need perfect data. You need enough signal to stop guessing. A light but honest check can save you from filing in a place that feels important but will not matter to your business.

Step two: understand the four “country buckets” that matter

Bucket A: core revenue markets

These are the places where you expect paid deployments, signed contracts, and renewals. If your plan is to sell into large companies, patents can support trust, procurement, and long sales cycles. They can also help you defend pricing when buyers compare you to cheaper copies.

For many deep tech founders, this bucket is the heart of the plan. You may not file in many countries, but you should file where the highest-value customers will judge you. That is where the patent turns into real business leverage.

Bucket B: strongest competitor markets

Competitors do not only copy your product. They also copy your pitch and your claims. If they sell in a market where you have patents, they need to think twice about how close they can get. That pressure can slow them down or force costly design changes.

Even if you do not sell there today, filing in a strong competitor market can still be smart. The goal is to block their easiest growth path. When you do that, you also look stronger to investors, because you are not only playing offense, you are also reducing risk.

Bucket C: manufacturing and supply chain hubs

For robotics and hardware-heavy AI, this bucket can be a big deal. If the key parts of your product can be made in a manufacturing hub and shipped worldwide, then your risk is not only about where you sell. It is also about where others can build.

When you have protection in a place where manufacturing is common, you can create pressure before the copy spreads. You may never operate there directly, but the patent can still matter because it targets the place where copying becomes cheap and fast.

Bucket D: partnership and exit magnets

Many early-stage teams do not think about exits yet, but your patent plan should still support future options. If likely partners or acquirers sit in certain countries, filings there can make diligence smoother. It can also reduce fear for the other side, because they see you took protection seriously.

This bucket is not about filing everywhere “just in case.” It is about filing where it helps you become easy to partner with and easy to acquire. That can have real value even before you reach scale.

Step three: score countries using a simple, honest system

Use scoring to prevent emotional decisions

When founders pick countries without a method, emotion sneaks in. Someone had a past job in a country, or a friend says a market is “big,” or a blog says you “must” file in certain places. Scoring keeps the decision clean and repeatable.

Pick a short list of countries that seem relevant. Then score each one on a few factors that match your business reality. This converts vague opinions into numbers you can discuss as a team.

The six factors that usually decide the answer

One factor should reflect near-term revenue, because that is the fastest way patents show value. Another factor should reflect competitor pressure, because patents often matter most when someone tries to crowd you.

You should also score manufacturing risk if you are hardware-heavy, and partnership value if your space has strong strategic buyers. Add enforcement practicality because a patent should be usable, not just printable. Finally, include budget fit so your plan stays real, not fantasy.

Enforcement practicality: the factor that changes everything

A patent in a country where enforcement is slow, unclear, or rarely respected can feel like protection but act like paper. You do not need to become a court expert, but you should be honest about whether a patent will create pressure in that place.

Sometimes enforcement practicality is not only about courts. It is also about whether companies in that market care about patents at all. In some places, businesses will avoid risk when they see protection. In other places, they may ignore it unless you are ready to fight.

Budget fit: make the plan survivable

Country choices are not only a legal topic, they are a cash topic. Filing, translating, and maintaining patents can add up fast. If your plan forces you to burn money that should go into product and pilots, it is not a good plan.

A good patent plan respects your runway. It fits your stage. It keeps options open without draining your core execution budget.

Step four: decide what “coverage” really means for your product

If your moat is an algorithm, country choices shift

When your core value is in software or a model-driven method, the important question is where that method is used in business. That often points to major commercial markets where enterprise software is bought and where competitors sell.

But you also need to account for differences in how software-related inventions are treated. In some places, the wording and framing matter more. Strong patents in this area often describe a real technical system with real inputs and outputs, not just abstract math.

If your moat is hardware, focus on “make” and “import”

When your moat is a mechanism, sensor layout, actuator system, or a unique physical structure, copying often happens through manufacturing. In that case, filing in places tied to manufacturing and import routes can be more valuable than filing in places that simply “feel large.”

Hardware patents can also help at borders and in supply chains. If a copy is being shipped into a key sales market, protection in that market can be used to create business pressure fast.

If your moat is a system, protect the full stack story

Many robotics and AI startups win because they combine parts into a system that performs better than any single piece. In those cases, you want patents that protect the overall system behavior, plus the key pieces that are easiest to copy.

This often lets you file in fewer countries while still creating real protection. Instead of spreading thin, you build a tight wall around what makes your product hard to match.

Step five: do the “copycat path” test

Imagine a competitor who wants to clone you in 12 months

This test is simple and it works. Pretend a strong competitor decides to copy your product and pitch. They will aim to build something “close enough,” then sell into your target buyers, then raise money by claiming the same outcomes.

When you think like this, you stop seeing countries as a checklist. You start seeing countries as pressure points. You ask where you can make copying harder, slower, or more costly.

Track where they would build, then where they would sell

For robotics, the build step often ties to suppliers, contract manufacturers, and assembly shops. For AI, the build step may tie to engineering hubs and deployment environments. In both cases, you should list the most likely “copy locations,” not the most famous ones.

Then track where they would sell first. Many copycats start in the easiest market to enter, not the biggest one. If you can block that early market, you can block their ability to show traction and raise.

Turn the path into a country shortlist

Once you see the copycat path, your country shortlist gets clearer. You pick places that either protect your revenue, block competitor growth, or reduce manufacturing risk. You do not file in places that do none of these.

This is how you avoid spending money for comfort. You spend money for leverage.

Step six: avoid the “country shopping” trap

More countries can create weaker protection

It sounds strange, but filing in more places can sometimes reduce quality. When budgets get stretched, teams may file quickly with weaker drafting, thinner claim coverage, or fewer variants. That can lead to patents that look impressive but do not block much.

A smaller number of strong filings often does more than a wide scatter of weak ones. Strong coverage is usually built through good claim planning and careful writing, not only through geography.

Maintenance fees are silent budget killers

Founders often focus on filing cost and forget that patents have ongoing fees. These fees can rise over time. If you pick too many countries early, your future self may be forced to drop patents later when cash is tight.

Dropping patents is not always bad, but you should choose it on purpose, not because you overreached. A plan that is easy to maintain is a plan you can actually keep.

Make every country earn its spot

A simple rule helps: every country should have a clear reason tied to revenue, competitor pressure, manufacturing, or partnerships. If you cannot say the reason in one clean sentence, it may not belong in the first wave.

This keeps your plan sharp. It also makes your story stronger in investor talks, because you can explain your choices without sounding unsure.

Step seven: use timing to keep options open without wasting money

Use early filings to lock your place in line

Timing is where many early startups win or lose. The key is to secure an early filing date with a strong application that captures the invention and the variations that matter. That early date can protect you while you learn more about markets.

This is why rushing a weak first filing is risky. If your first filing is thin, you may lock yourself into weak protection everywhere you extend later. Strong first work can save you money and regret later.

Decide later only works if the first filing is strong

Many founders like the idea of deciding countries later, and that can be smart. But it only works if your first filing is written well, with enough detail to support broad claims later. Without that, waiting does not help, because you cannot expand beyond what you first described.

So “we will choose later” is not a plan by itself. It is a timing tool that depends on quality today.

Align timing with real business milestones

A clean way to plan is to align big patent spending with milestones like paid pilots, major partnerships, or a clear shift into a new region. This keeps your IP spending tied to proof, not hope.

It also reduces stress. Instead of feeling like you must decide everything at once, you build the plan in steps that match your progress.

Step eight: make the decision investor-proof

Investors want to see that you are thinking clearly

Most investors do not want you to file everywhere. They want to see that you understand risk and that you can explain your plan. A calm, logical country strategy shows that you are building a company, not just building tech.

When you can explain why each chosen country matters, you reduce questions and increase trust. That can matter a lot in early rounds, where confidence is part of the product.

A simple narrative beats a long list

A short, clear narrative is often stronger than a long list of countries. You can say your filings match your first revenue markets, your main competitor markets, and the most relevant manufacturing routes. That tells an investor you are not wasting money and you are not blind to threats.

This also helps later during diligence. Clear reasons are easier to defend than vague tradition.

This is where Tran.vc often helps the most

Many founders have strong inventions but no clear filing map. Tran.vc supports teams by shaping a strategy that fits the business plan, then turning it into filings that are built to hold up. The goal is not paperwork. The goal is leverage that makes your company harder to copy and easier to fund.

If you want help building an IP plan that matches your product and market, you can apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/