Every founder I meet wants the same thing: build something real, move fast, and still protect what they’ve made. The hard part is that “international IP” sounds expensive, slow, and full of traps.

It doesn’t have to be.

If you treat global IP like a smart rollout (not a massive one-time purchase), you can protect your core work in the right places, at the right time, without burning your runway. And if you’re building in AI, robotics, or deep tech, this matters even more—because your edge is often in the method, the system, the data flow, the control loop, the architecture, and the “how,” not just the UI.

At Tran.vc, this is exactly what we help technical founders do: turn inventions into defensible assets early, with real patent strategy and filings as in-kind support (up to $50,000 in IP services), so you don’t overpay, under-protect, or end up with paperwork that doesn’t scare competitors. If you want help, you can apply anytime here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Before we go deeper, here’s the single most important idea to hold onto:

International IP is not a “file everywhere” problem. It’s a “choose your moments” problem.

Most overspending happens when founders do one of these:

They file too broadly too early, before the product is stable.

They file in countries because they “feel important,” not because the business needs it.

They pay to draft patents that don’t match what’s actually valuable in the tech.

They rush into translations and national filings without using the time buffers the system already gives them.

So in this article, we’re going to build a clear, calm plan. Not a generic plan. A plan you can actually use while you’re shipping product, selling pilots, and hiring your first team.

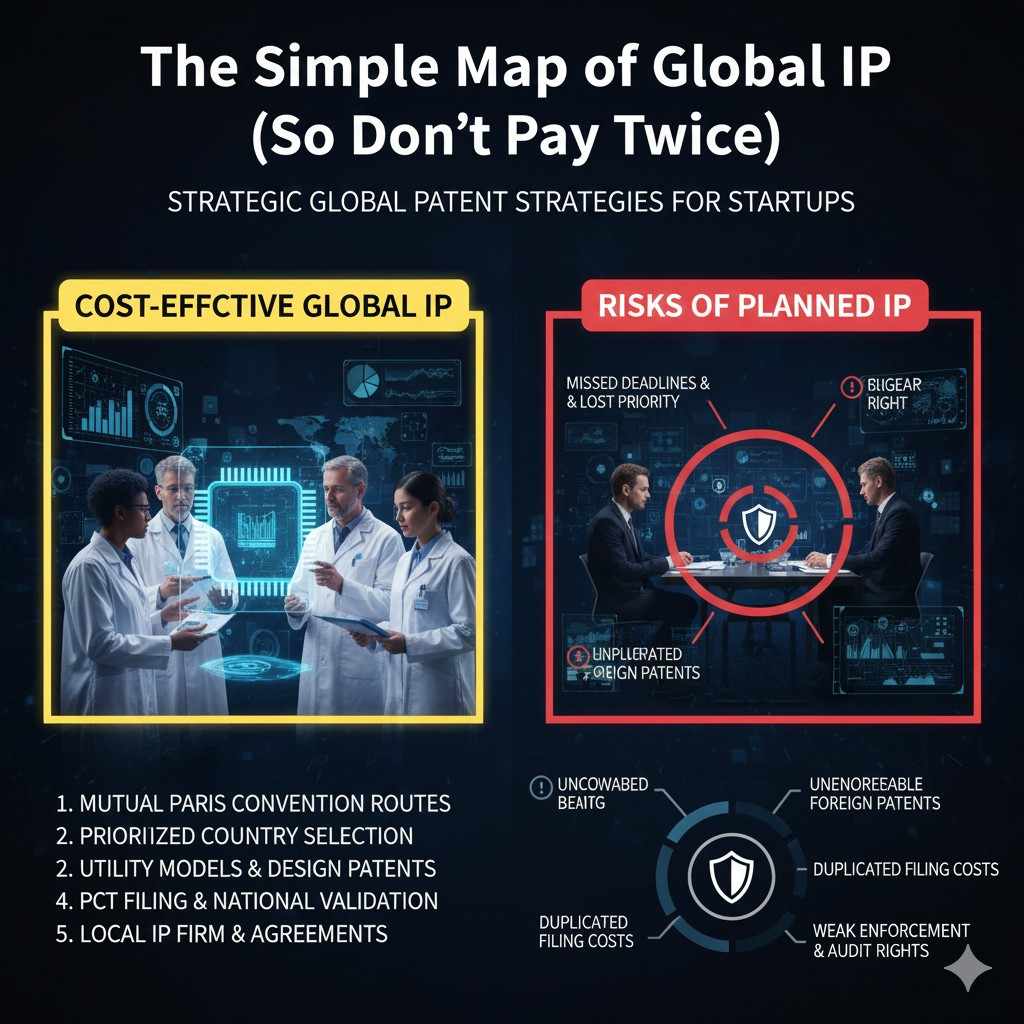

The simple map of global IP (so you don’t pay twice)

Let’s make this plain.

A patent is not “global.” A patent is a set of rights in a specific place. If you want coverage in five countries, that usually means five separate steps and five sets of fees over time.

The good news: you do not have to commit to every country on day one.

There are “paths” that let you start small, then expand later—only if the business proves it’s worth it. That is the core of controlling spend.

Most founders start with one of two first moves:

You file in your home country first (often a provisional in the US, or a first filing elsewhere).

Or you file a formal first application (a non-provisional or its equivalent) as your base.

Then, you use a system called the PCT route (Patent Cooperation Treaty) to “hold your place” in many countries without paying full costs right away.

Think of PCT like a reservation system. You don’t buy every ticket immediately. You reserve the option to buy later, once you know which trip is real.

This is where disciplined founders win.

They use early filings to lock a priority date (the “this is when we claimed it” date), then they use the PCT timeline to gather proof, refine product, and decide where protection will actually pay back.

And yes, there are other routes too, like filing directly in selected countries or using regional systems, but for most deep tech startups, the “start focused, then use PCT to keep options open” approach is the most practical way to avoid overspending while staying protected.

The first place founders waste money: filing before they know what the invention is

This sounds harsh, but it’s very common.

A team builds an early prototype. They hear “file early or you lose it.” They panic. They file something broad. Later, the product evolves and the real magic shifts. Now the patent doesn’t match the real moat.

So they file again.

That second filing can be the right move—but it often happens because the first one was rushed and vague. That’s where spend balloons. Not because patents are always expensive, but because founders pay twice for the same learning.

Here’s the better way to think about timing:

You don’t file because you built “a product.” You file because you can describe a repeatable technical method that is likely to stay true even as the product grows.

In AI and robotics, the product can change fast, but the core method often stays steady. For example:

A training method that handles noisy labels in a special way.

A motion planning approach that reduces compute while keeping safety bounds.

A sensor fusion method that handles failure modes better than standard stacks.

A system architecture that cuts latency across edge devices.

A control scheme that stabilizes under certain conditions with less power.

Those are the kinds of “staying power” inventions you want to anchor early.

A practical test: if you can explain the invention to another engineer and they can implement the key steps from your description, you likely have something you can protect. If the invention is “we are still exploring,” then the filing may be premature.

The goal is not perfection. The goal is accuracy.

When the filing matches the true value, your later filings become expansions, not repairs.

The second place founders waste money: choosing countries based on ego

International IP spend should follow business reality, not pride.

A smart question is not “Where do we want to be big someday?”

A smart question is “Where do we have exposure soon?”

Exposure usually comes from four places:

Where you will sell.

Where you will manufacture.

Where your biggest competitors operate.

Where a copycat could produce and ship cheaply.

If you’re selling robotics to factories in Germany and Japan, that’s real exposure. If you “might expand to Europe later” but you don’t even know your first market, Europe can wait.

This is where many teams overspend: they treat global filing like buying a world map, instead of placing a fence around the yard they actually use.

A disciplined approach is to pick a small “first ring” of places that matter in the next 12–24 months, then keep optionality for the second ring using the right legal path.

That one change—decisions based on near-term exposure—often cuts global IP cost in half without reducing protection where it matters.

The timeline trick that keeps costs under control

Here is the part founders rarely hear clearly:

International patent systems often give you time buffers.

If you use them well, you delay the biggest costs until you have better data: customer demand, revenue signals, competitor behavior, fundraising progress, and technical stability.

A common pattern looks like this:

You file early to lock the priority date.

Then you wait while you build.

Then you use the allowed window to decide where to enter nationally.

That window is not “free time.” You still need strategy and good drafting. But it is a huge lever for cash flow.

The mistake is when founders burn that window doing nothing, then rush at the end and pay premium fees, urgent translations, and rushed decisions.

The calm way is to use the window intentionally:

Use the time to gather customer proof.

Use the time to refine claims based on what is shipping.

Use the time to map which countries matter based on actual pipeline.

Use the time to watch competitors and see where they file.

Use the time to tighten your story for investors.

When you do this, the big spend becomes a choice you make with confidence—not a bill that shows up at the worst time.

This is also why Tran.vc’s model exists. We support founders early with real patent strategy and filings as in-kind services, so you can build the right foundation without draining cash meant for product and sales. If that would help, apply here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

How to protect globally without filing everywhere

Let’s talk about “coverage” in a way that matches reality.

Founders often imagine they need one patent per country per feature. That’s not how it works when you’re being smart.

You can get strong global protection by doing two things well:

Drafting patents that cover the core method in a way that is hard to design around.

Picking jurisdictions that block the most dangerous paths for copycats.

A good patent is not “we built a robot.” A good patent is “we built a specific system that does X in a way others cannot easily copy without infringing.”

This is why claim design matters so much.

If your patent is too narrow, competitors go around it.

If it’s too broad without support, it gets rejected or later challenged.

If it’s written like marketing, it won’t stand up.

If it’s written like a research paper without practical detail, it won’t stand up either.

Good drafting is a balance: clear structure, many variations, strong examples, and claims that match real implementation.

And here is the key cost point: the better the first draft, the less you spend later.

Because later spend often comes from fixing a weak foundation.

A tactical way to decide what to patent first

Most teams have more inventions than they think. The trick is picking the one that will carry the most value.

A simple approach is to look for the “choke point” in your product. The step that is hardest to replicate without your know-how.

In robotics, it might be a calibration method that keeps the system stable in the real world.

In AI, it might be a data pipeline method that improves performance with less labeled data.

In edge systems, it might be an architecture that reduces bandwidth and improves privacy.

In autonomy, it might be the way your system handles rare events safely.

You want to patent the choke point first because:

It is harder to replace.

It tends to remain consistent as the product evolves.

It is easier to explain as a “method” with steps.

It maps nicely to claims that are enforceable.

If you start with “nice-to-have” features, you may still get patents, but you won’t get leverage. And leverage is the whole point: leverage with competitors, leverage in fundraising, leverage in partnerships.

One more cost trap: confusing patents with secrecy

When a patent is the right tool

A patent is best when someone else can copy your work by looking at your product, testing it, or reading public papers. Many robotics and AI systems leak their method through behavior, performance, or integration. If a capable team can rebuild the core approach in six months, you are in patent territory.

A patent also helps when you will need to share details with buyers, partners, or large enterprises. In deep tech, sales cycles often require technical deep dives. If your plan depends on “we can’t explain it,” you will lose deals. A patent lets you share the story with more comfort.

When a trade secret is the smarter move

Trade secrets work when the secret stays hidden during normal use. Internal tuning methods, training recipes, data cleaning steps, and operational workflows can sometimes stay private for years. If a competitor cannot discover it without inside access, secrecy can be cheaper and stronger.

But trade secrets need discipline. If your team shares details in demos, decks, pilots, or support channels, you may lose the secret without realizing it. Patents cost money, but accidental leaks can cost the whole moat.

How to choose without overthinking

A useful rule is this: if you must show it to sell it, lean patent. If it stays inside your walls and is hard to reverse, consider secrecy. Many winning teams use both, but they decide on purpose, not by habit.

If you want help making this call with a real patent strategy lens, Tran.vc can support you with in-kind IP services up to $50,000. You can apply anytime here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

The lowest-cost global strategy that still looks strong to investors

Start with a tight “core” invention

Investors don’t fund you because you filed “a patent.” They fund you because your IP supports a real moat. The cheapest strong plan starts with one core invention that sits at the center of the product and is hard to swap out.

In AI, this could be a training or inference method that reduces compute while keeping accuracy. In robotics, it could be a control, calibration, or safety method that keeps performance stable outside the lab. When the core is right, each new filing becomes an extension, not a rescue.

Use the global system to buy time

The most founder-friendly move is to secure an early priority date, then use the international process to delay the expensive country-by-country step. That delay is not laziness. It is a financial tool.

During that time, you can test your market, improve the product, and watch competitor behavior. You are making the later spend smarter because you’re choosing countries with proof, not hope.

Make “country choice” a business decision, not a legal one

A clean way to frame it is to ask: where do we make money, and where could a copycat hurt us? If your revenue will come from a few regions, those regions deserve priority. If your manufacturing is concentrated, that supply chain region matters too.

This approach does two things at once. It keeps costs down, and it makes your IP story easy to explain in a pitch. That clarity itself can help fundraising.

How to pick countries without getting trapped in fear

Follow your near-term revenue

Your first international filings should usually match where you expect signed customers in the next 12 to 24 months. If the deal pipeline is mostly in one region, spending heavily elsewhere can be a cash leak.

This does not mean you ignore future markets. It means you use the timeline buffers to keep the option open while you validate where traction is real.

Block the easiest copy paths

Sometimes a country matters because it is a common place to build and ship from. Even if you don’t sell there, it can still be a source of copies that flood your customer markets. You don’t need to cover every location, but you do want to avoid leaving a wide-open door.

The right answer depends on your product type. Hardware-heavy robotics has different exposure than pure software. A good strategy will treat those as separate risk shapes, not as the same template.

Watch where competitors file

Competitors tell you what they fear by where they spend. If a serious competitor is filing in certain places, it can signal where enforcement and market value are highest in your space.

This does not mean you copy them blindly. It means you use their filings as evidence, the same way you use customer pipeline as evidence. Evidence-based choices cost less and protect more.

Drafting choices that quietly save you tens of thousands

Don’t pay for a “pretty” patent—pay for a usable one

Overspending often starts with a draft that looks impressive but lacks real depth. A usable patent shows the method clearly, includes variations, and supports broader claim coverage with specific examples.

In deep tech, you want your patent to read like a careful build guide, not like a press release. The goal is to make it hard for others to copy without stepping on your claims.

Write for the product you will ship, not the demo you showed

Early demos are often fragile. If your filing locks into demo details that won’t survive, you may end up paying to refile when the real product is ready.

A better drafting approach focuses on what will remain true: the system steps, the data flow, the control logic, the architecture constraints, and the performance outcomes tied to specific technical choices. That kind of writing stays valuable even as the UI and packaging evolve.

Include enough variation so competitors can’t “step around”

Competitors rarely copy you line by line. They copy the concept and adjust the edges. If your patent only describes one narrow setup, it becomes easy to avoid.

This is where thoughtful variations matter. Different sensor types, different model families, different deployment settings, different hardware limits, and different data sources can all be described in one strong filing. Done well, it reduces the need for multiple separate filings later.

Budget control: how to plan IP spend like a product roadmap

Think in phases, not one giant bill

International IP becomes affordable when you plan it like you plan engineering. You don’t build every feature in month one. You choose the highest-leverage feature, ship it, then expand.

Treat your IP the same way. Phase one locks the core invention and priority date. Phase two adds expansions based on what customers pay for. Phase three widens country coverage once the market is proven.

This keeps you from paying for “maybe.” You pay for “we know.”

Tie filings to business milestones

A clean way to avoid overspending is to connect filings to events you can measure. For example, a signed pilot, a paid deployment, a key partnership, or a new technical breakthrough that changes your moat.

When you do this, IP spend stops being emotional. It becomes a planned investment that follows traction.

Use fundraising moments wisely

A strong IP story can help fundraising, but only if it is real and well framed. Investors don’t want a pile of random filings. They want a coherent story: what is protected, why it matters, and how it blocks competitors.

If you align your filings with fundraising windows, you can show momentum without burning cash too early. Tran.vc helps founders do exactly this planning and execution with in-kind IP services up to $50,000. Apply anytime here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Common founder mistakes that inflate international costs

Rushing into translation and national filings too early

The biggest global costs often show up when you start entering many countries and paying translation and local fees. If you do this before you have real market proof, you are spending in the dark.

The calmer approach is to use the time you have to learn, then decide. Late decisions made with real data are cheaper than early decisions made with fear.

Filing too many “small” patents instead of one strong foundation

Many founders think more filings equals more protection. But a stack of narrow patents can be easier to ignore than one well-drafted core filing.

A strong foundation can also support later additions. When the first filing is deep and clear, later work becomes more efficient.

Letting IP become a side project

IP fails when it is treated as paperwork. The best teams integrate it into product thinking. They capture inventions as they build, keep notes, and treat “what’s new here” as a habit.

This habit reduces legal time, reduces drafting cycles, and reduces missed inventions. It also makes your team faster at explaining value to partners and investors.