If you are building real tech, your biggest fear is not “no one wants it.”

It is: a bigger company sees it, copies it, and ships it faster than you can.

Patent claims are one of the few tools that can stop that from happening. Not the patent title. Not the drawings. Not the story in the patent. The claims.

Claims are the legal “fence” around what you built. If the fence is placed well, a bigger competitor cannot step inside without paying you, partnering with you, or spending real time to design around you. And time is the one thing even a giant company hates to waste.

This article will show you, in plain words, how to use patent claims as a practical blocking tool. Not theory. Not “patent 101.” The goal is to help you think like a builder and a strategist at the same time: where to place the fence, how wide to make it, what doors to leave open, and how to make the fence hard to climb.

Tran.vc helps founders do this early, while the product is still forming, so the fence is built into the roadmap—not stapled on later. If you want a partner that invests up to $50,000 in in-kind patent and IP work, you can apply anytime here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Before we go deeper, here is the core idea you should keep in your head the whole time:

A patent does not block a competitor because it exists.

It blocks a competitor when your claims match what they must do to get the same result your users want.

That is it. Everything else is just the method.

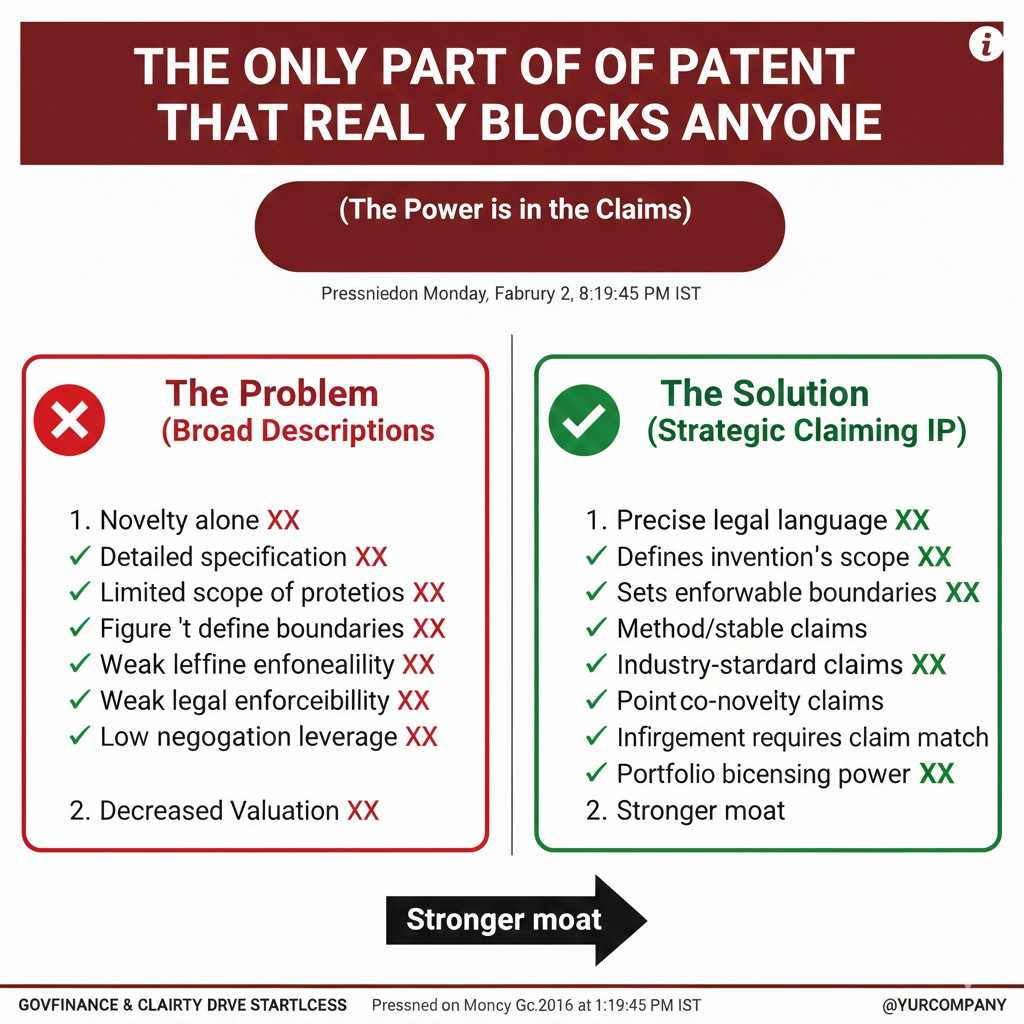

The only part of a patent that really blocks anyone

Think of a patent like a house listing.

- The description is the photos and the tour.

- The drawings are the floor plan.

- The claims are the property lines on the map.

If a competitor stays outside your property lines, you cannot stop them. Even if they copied your idea “in spirit.” Even if their product looks the same to customers. Patent law does not care about vibes. It cares about whether their product or method has each required piece in your claim.

This is why so many startup patents “feel” strong but do not scare anyone. The founders wrote a beautiful story about what they built, but the claims ended up narrow, or easy to avoid, or focused on a feature no one needs.

So when we say “use patent claims to block bigger competitors,” we mean this:

- Identify what the competitor must do to compete.

- Claim that—carefully—so they cannot do it without stepping into your claims.

And you can do this without being loud or aggressive. You do it quietly, with good claim work, early.

How big competitors actually copy startups

Big companies do not usually copy line-by-line code. They copy outcomes.

They look at a product and ask:

“What is the user getting here, and how can we deliver that with our scale?”

If you built a robotics system that picks items faster, they will not copy your exact motors or your exact data pipeline. They will try to reach the same picking speed, the same error rate, the same cost, the same safety level.

If you built an AI model that makes support tickets 60% cheaper, they will try to get the same cost drop with their own stack.

So your claims must be aimed at the path to the outcome.

This is where many founders miss the mark. They claim the “cool” part. The clever trick. The neat architecture. But the bigger company does not need your trick. They need the outcome.

Your job is to claim the steps that are hard to avoid if they want the outcome.

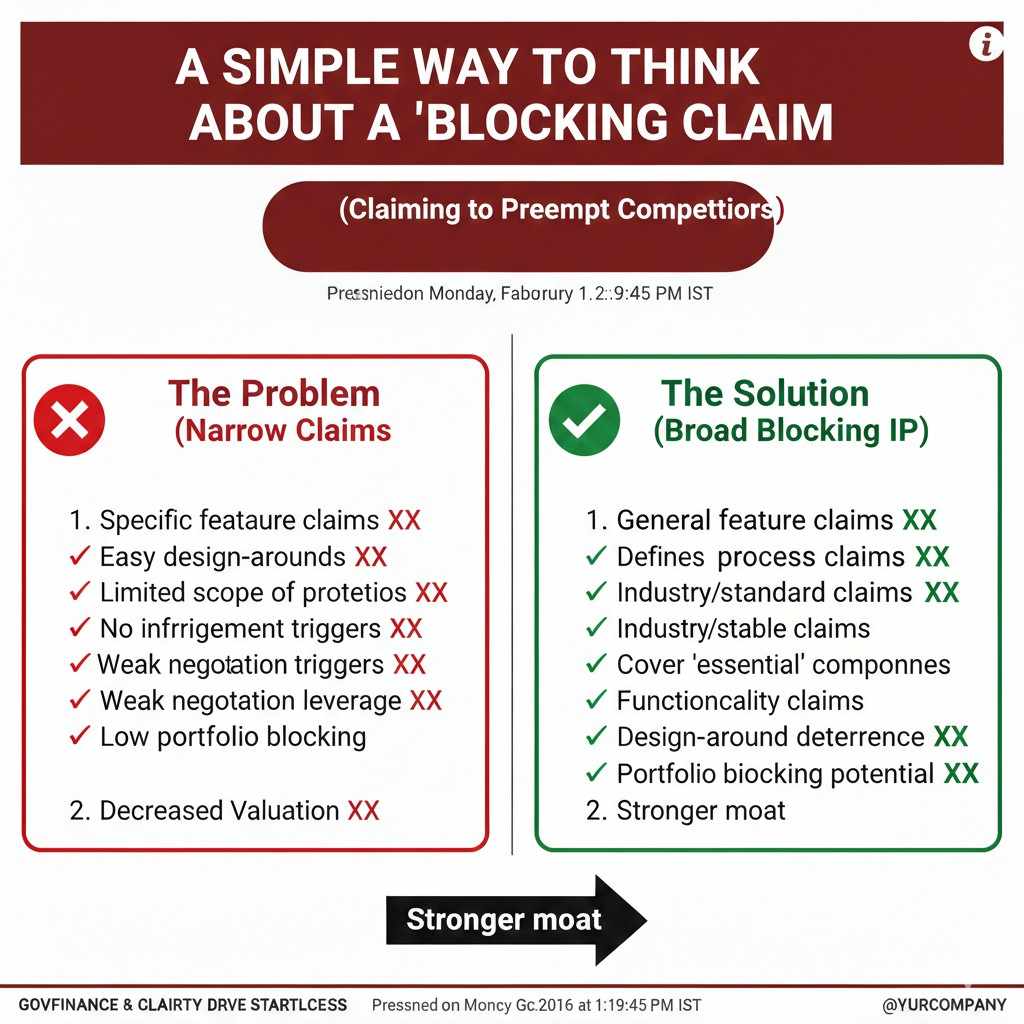

A simple way to think about a “blocking claim”

A blocking claim is not “broad.” A blocking claim is “unavoidable.”

Unavoidable means: if they want to compete, they end up doing the steps you claimed, or using the parts you claimed, because it is the cleanest, safest, cheapest path.

There are two main ways to do this.

1) Claim the standard path

Sometimes there is a path the whole market will use. Like an emerging “default” workflow. If you see it early, you can claim key parts of it before it becomes normal.

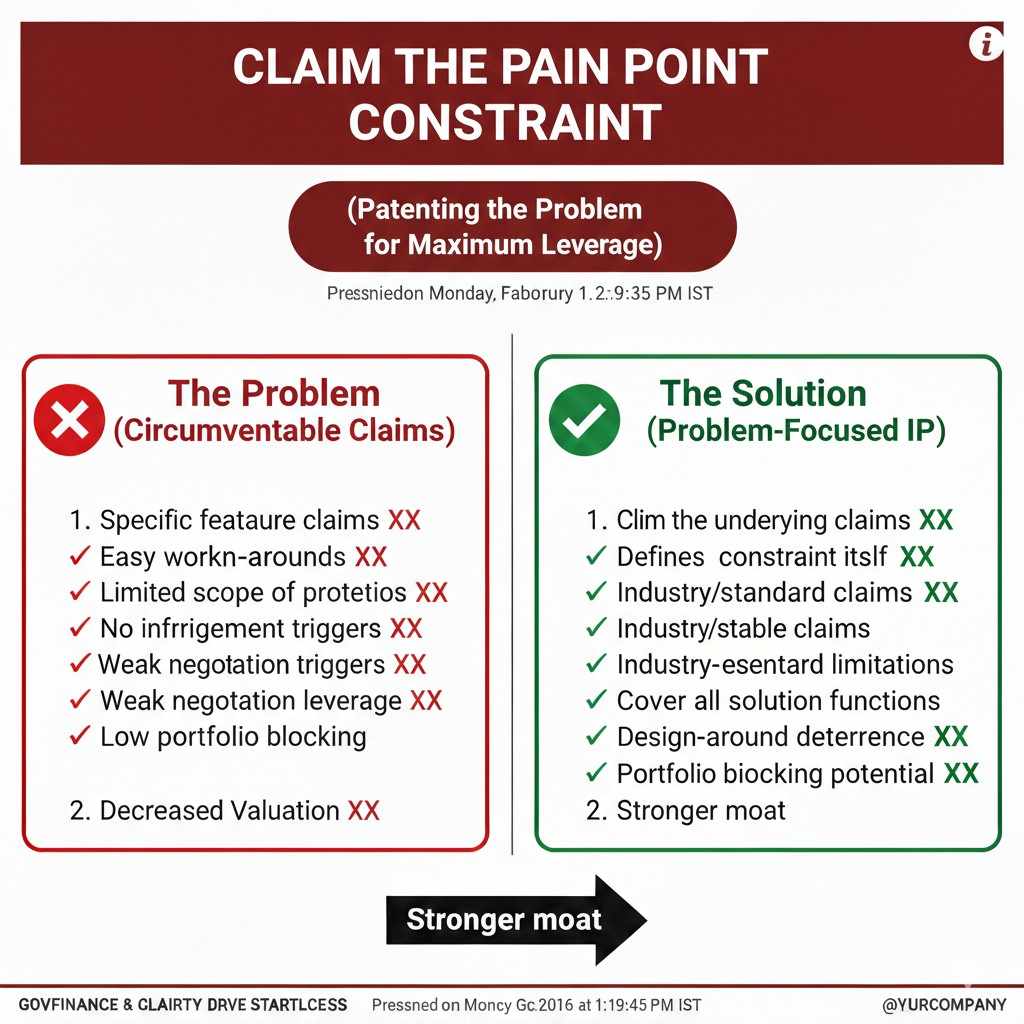

2) Claim the pain point constraint

Other times the market has a hard constraint. Like latency, power, heat, sensor noise, compute limits, safety rules, or human trust. If your method is the first clean way around that constraint, you can claim the workaround.

In deep tech, constraints are often the better bet. They do not change fast. A competitor can swap UI colors. They cannot rewrite physics.

What makes a claim easy to “design around”

Design-around is when a competitor stays outside your property lines.

Some design-around is fair and normal. But when your goal is to block a larger player, you want to reduce easy escapes.

Here are a few common “escape hatches” that make claims weak:

If your claim has too many required steps, they can remove one step and avoid it.

If your claim depends on one exact sensor type, they can swap a sensor.

If your claim depends on one exact order of steps, they can reorder steps.

If your claim uses fuzzy words like “smart,” “optimal,” or “improved,” it can be attacked as unclear.

If your claim describes a specific example instead of the general rule, it will be narrow.

This is why claim drafting is not just legal writing. It is game design. You are building a maze where the best paths all run through your claim.

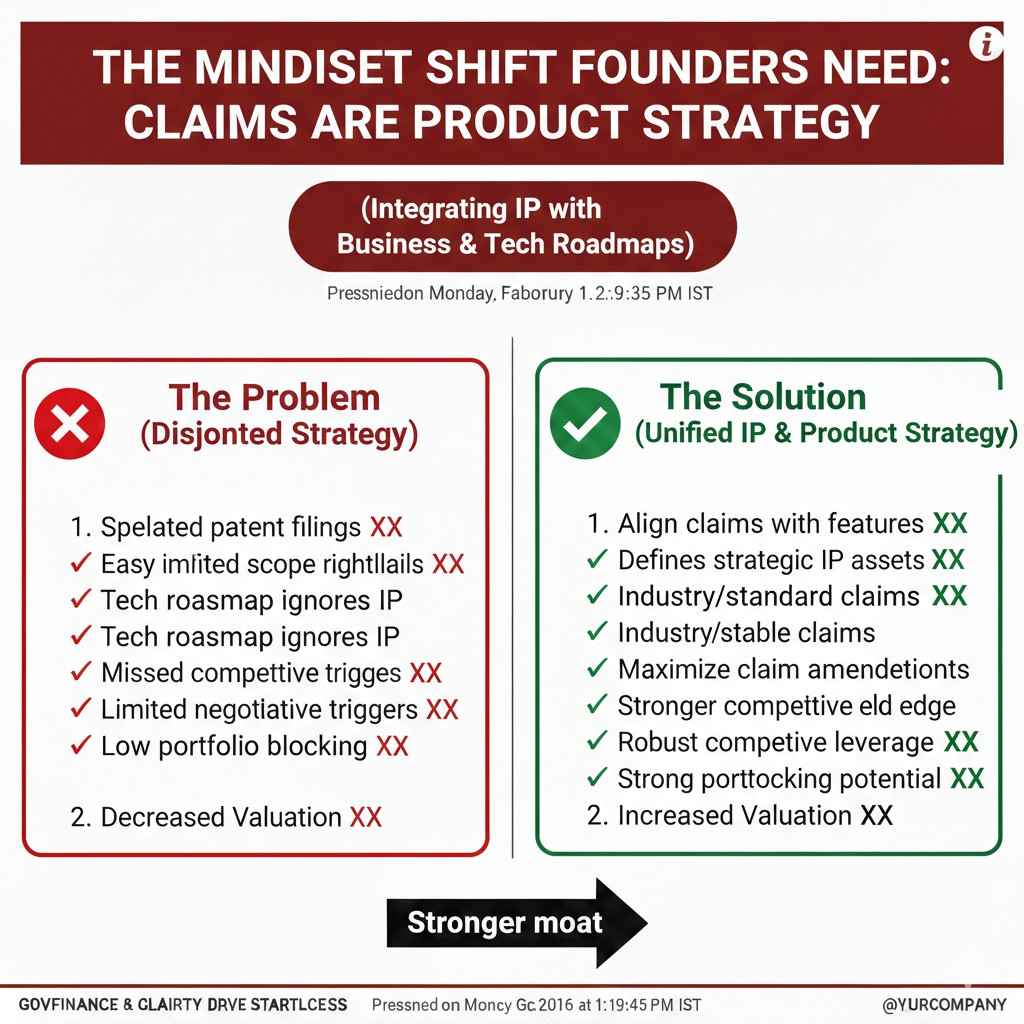

The mindset shift founders need: claims are product strategy

The best claim plans are not written after the product is “done.”

They are written while the product is still forming. Because claims shape what you choose to build first. They shape what data you collect. They shape what you measure. They shape the experiments you run.

When we work with founders at Tran.vc, the best outcomes happen when the patent plan and the build plan are tied together. The patent is not an extra task. It is part of the roadmap.

And when you do it this way, something interesting happens:

Even if you never sue anyone, your claims can still block.

Because they give you leverage in partnership talks, licensing talks, and fundraising. Bigger companies see the fence and choose the easier path: partner, buy, or pivot away.

If you want to build that kind of leverage early, you can apply anytime: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

The “claim stack”: one fence is not enough

Blocking bigger competitors usually takes a set of fences, not one.

But we will keep this simple and avoid heavy lists.

Think of three layers:

- A wide fence around the core result (hard to avoid).

- A tighter fence around your best implementation (hard to match performance).

- A set of small fences around key sub-parts (hard to copy fast).

Why layers matter: if you only have the wide fence, it might be challenged. If you only have the tight fence, it might be easy to avoid. Together, they create pressure from multiple angles.

Even when a big company can avoid one layer, another layer catches them.

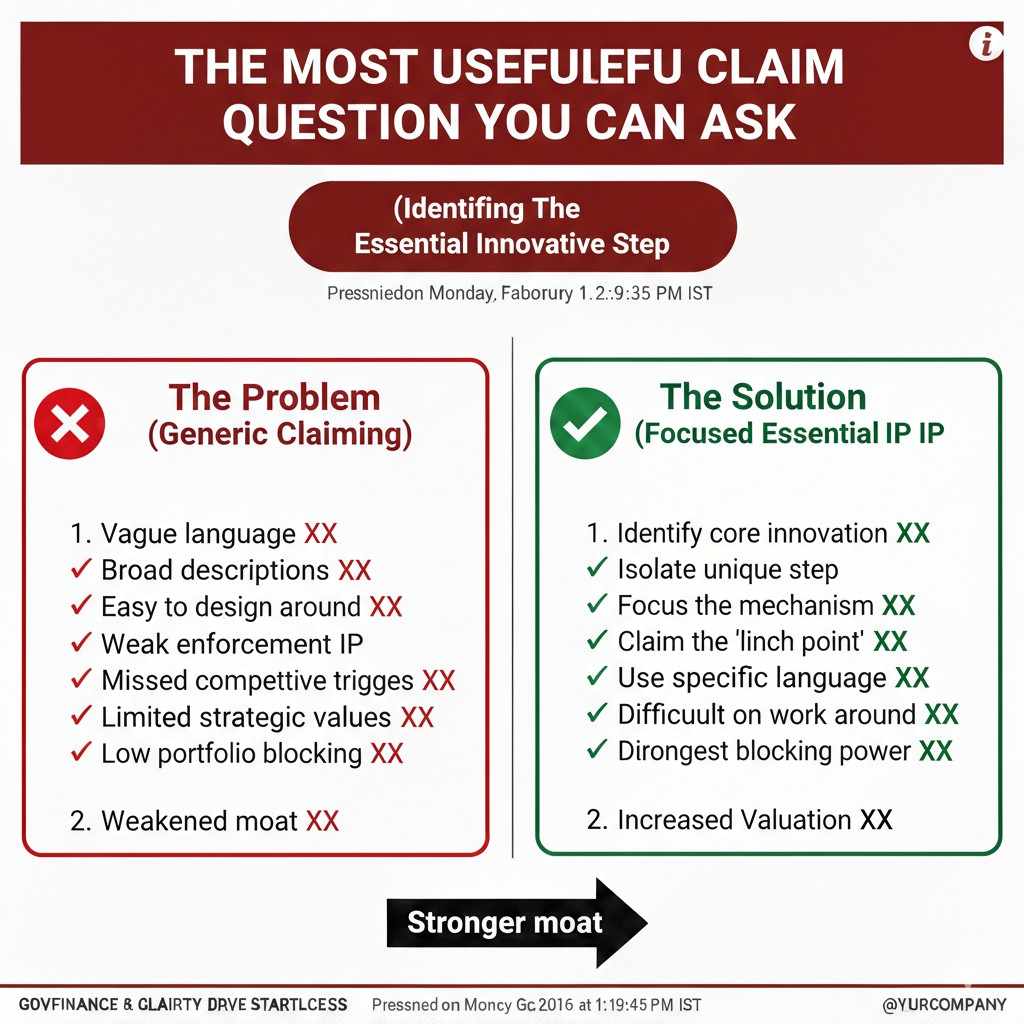

The most useful claim question you can ask

When you are thinking about claims, do not start with:

“What did we build?”

Start with:

“If a big competitor tries to beat us, what will they ship?”

Then go one step deeper:

“What will they be forced to do under the hood to make it work well?”

That “forced” part is where blocking power lives.

Here is a quick example in plain terms.

Say you built a warehouse robot that can move fast without tipping when it turns.

A weak claim might focus on your exact control code, or your exact sensor model.

A stronger blocking claim might focus on the idea that to move fast and not tip, you must measure or estimate a stability value in real time and adjust motion based on it. Because no matter who builds it, if they want speed plus safety, they will need some form of that.

That is closer to unavoidable.

We will get more tactical in the next sections. We will talk about how to find the “forced” steps, how to claim them without overreaching, and how to write claims that make design-around costly.

Why startups can win this game even against giants

You might think: “But big companies have huge legal teams.”

True. But big teams do not guarantee good claims.

Startups have one major advantage: closeness to the invention.

You know why each decision was made. You know what failed. You know which workaround finally made the system stable. You know what tradeoff the product cannot live without.

That is gold for claim strategy. It helps you claim the true inventive step, not the surface details.

Also, big companies move slower in new areas. Their teams often wait until a market is proven. That delay can give you time to file first and place the fence.

That is why early IP work matters so much for AI and robotics. The best time to claim is when the market is still forming.

Tran.vc was built around this idea: help technical founders lock in the fence early, with real patent strategy and filings, without forcing them to raise VC too soon. If that sounds like what you need, apply here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form.

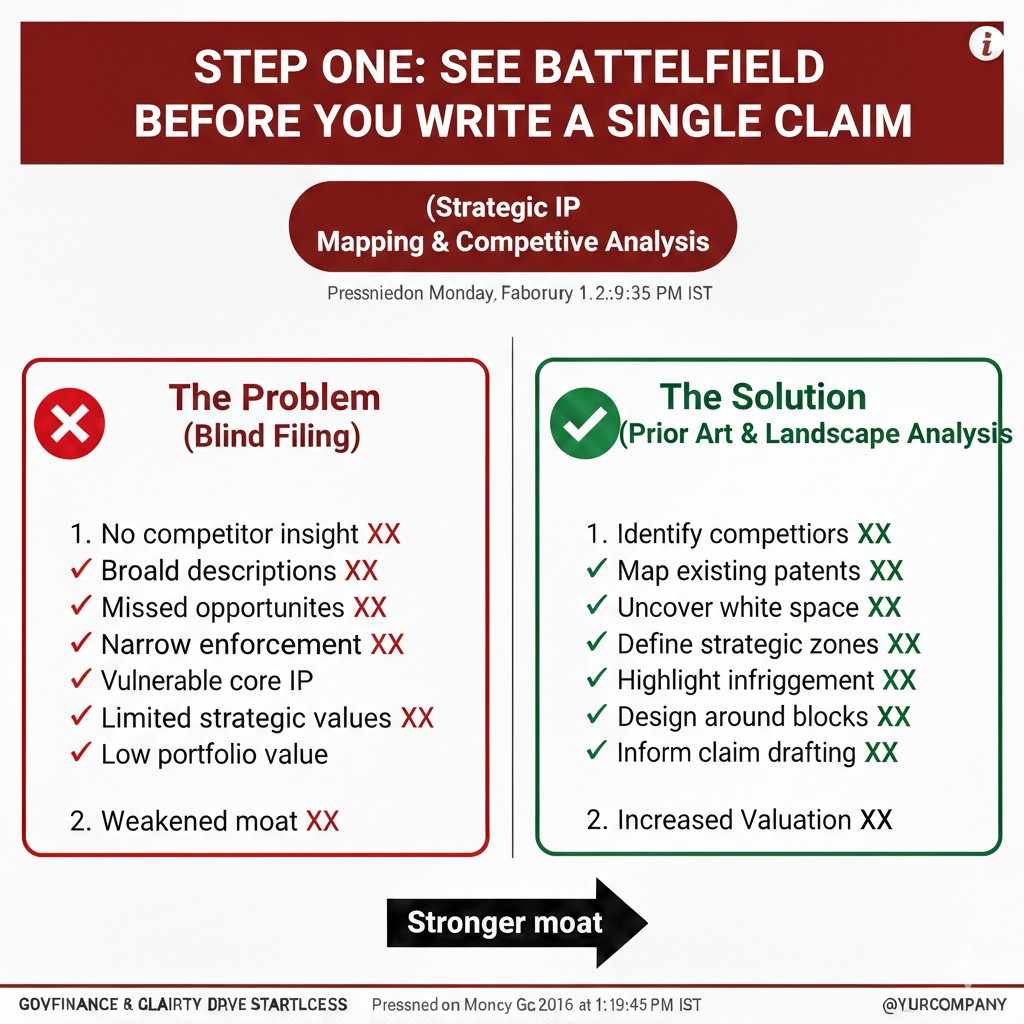

Step One: See the Battlefield Before You Write a Single Claim

Understand How a Bigger Competitor Thinks

Before you draft anything, you must slow down and study how a large company will react to you. Big companies do not panic. They observe. They wait. Then they move with force.

They ask one simple question: “Is this market worth owning?” If the answer is yes, they assign a team. That team does not try to copy you line by line. They try to build a version that fits their systems, their supply chain, and their cost structure.

Your job is to predict that move before it happens. When you understand how they think, you can place your patent claims directly in their path.

This is not about being aggressive. It is about being prepared.

Map the Outcome They Must Deliver

Every product delivers an outcome. That outcome is what customers care about.

If you built an AI model that cuts fraud by half, the outcome is not your model architecture. The outcome is lower fraud with acceptable false positives. If you built a robot arm that moves twice as fast without losing accuracy, the outcome is speed with precision.

A bigger company that enters your market must hit that same outcome. They cannot sell something worse. Customers will not accept it.

So you must ask yourself: what must they technically do to reach that outcome?

When you answer that question honestly, you begin to see where your claims should live.

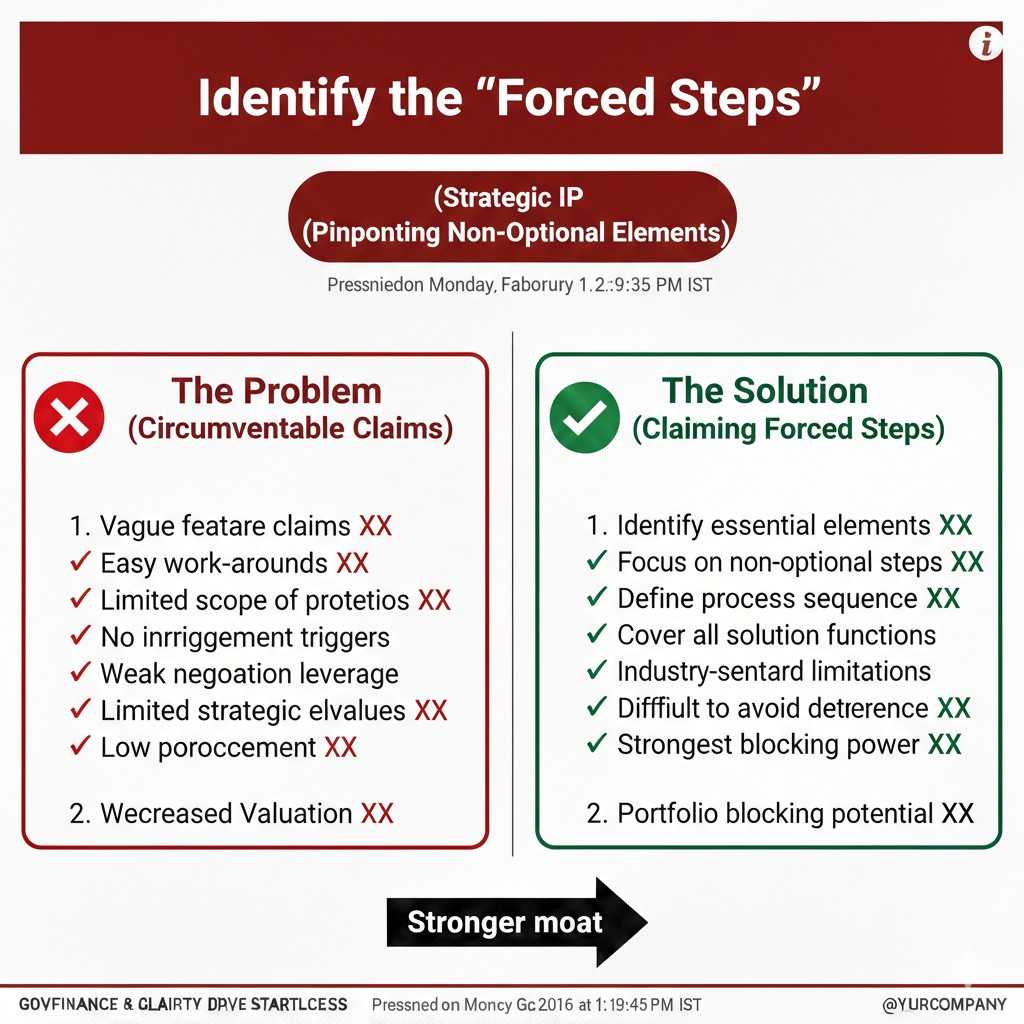

Identify the “Forced Steps”

A forced step is something no competitor can avoid if they want the same result.

In robotics, it may be a real-time calibration loop. In AI, it may be a certain type of feedback integration. In hardware, it may be a power management method that prevents heat spikes.

These are not cosmetic choices. They are structural necessities.

When you find these forced steps, you are close to writing a blocking claim.

This is where deep technical founders have an edge. You understand which parts of your system are optional and which parts are essential. That insight is the foundation of a strong claim.

If you want expert help identifying these forced steps early, before competitors even notice you, you can apply to Tran.vc here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Step Two: Turn Your System Into Claim-Ready Building Blocks

Break Your Product Into Functional Pieces

Most founders describe their invention as one big system. That is natural. You built it as a whole.

But claims do not work well when everything is bundled together. If you claim the entire system with all its details, a competitor can remove one small piece and escape your fence.

Instead, you must break your product into functional pieces. Think in terms of modules, processes, and decision points.

For example, in an AI pipeline, you might have data intake, feature transformation, model training, inference control, and feedback adjustment. Each of these can be studied separately.

When you isolate them, you begin to see which pieces carry real strategic weight.

Separate Core Logic From Implementation Details

There is always a difference between what your system does and how you built it.

The core logic is the rule that makes the system work. The implementation is your chosen way of expressing that rule.

If you confuse the two, your claim becomes narrow.

For example, imagine your robotics system balances itself using three specific sensors arranged in a certain way. The core logic may not be the exact sensor placement. It may be the dynamic estimation of center-of-mass shift and the control adjustment based on that estimate.

If you claim only the specific sensors, a competitor swaps them and avoids you.

If you claim the dynamic estimation and control adjustment concept, it becomes much harder to design around.

This distinction is subtle but powerful.

Write Claims That Capture the Rule, Not Just the Example

When you work with experienced patent counsel, the goal is to describe the invention broadly enough to cover variations, yet precisely enough to remain valid.

You want language that reflects the underlying rule of your system.

For example, instead of claiming “a camera positioned at a 45-degree angle,” you might claim “a sensor configured to capture spatial orientation data for stability control.”

The second version allows room for different hardware implementations while still covering the essential function.

This is how you make your claim resilient.

At Tran.vc, we spend serious time here. We work closely with founders to extract the real rule behind their code or hardware. That work becomes the heart of the claim strategy. If you are building something deep and defensible, apply here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Step Three: Draft Claims That Make Design-Around Expensive

Reduce Easy Escape Routes

A weak claim is easy to step around. A strong claim forces competitors to take a longer, more costly path.

You do this by avoiding unnecessary limitations. Every extra requirement in a claim is a potential escape route.

If your claim says the method must use five steps, and one of those steps is not essential, a competitor can remove it. Now they are outside your fence.

So you must carefully ask: is this step required for the outcome, or just part of our version?

This discipline takes humility. It requires you to separate what feels clever from what is structurally necessary.

Think in Terms of Economic Pressure

Blocking does not always mean stopping someone completely. Often, it means raising their cost.

If your claim covers the most efficient way to achieve an outcome, a competitor may still build an alternative. But it may be slower, more expensive, or less reliable.

That difference can be enough to protect your market position.

In AI and robotics, efficiency often drives adoption. If your claims protect the efficient path, you create real leverage.

This leverage matters during fundraising, partnership talks, and even acquisition discussions. Investors and buyers look closely at whether your claims create economic pressure on competitors.

Layer Your Claims for Strength

A single broad claim is rarely enough.

You want a broad claim that covers the main concept. Then you want narrower claims that protect specific high-performance implementations.

The broad claim creates general coverage. The narrower ones protect your optimized version.

If the broad claim faces challenge, the narrower ones still stand.

This layered approach creates durability. It also signals seriousness to anyone reviewing your portfolio.

Building this kind of structure takes planning. It cannot be rushed the week before a funding round.

That is why Tran.vc works with technical founders at the earliest stages. We invest up to $50,000 in in-kind patent and IP services so you can build the fence while you build the product. You do not need to give up control early just to afford strong IP.

If that model fits your journey, you can apply anytime at: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/