AI rules are getting strict. And the biggest question most founders now face is simple: will anyone label our AI as “high-risk”? If the answer is “maybe,” you want to know early—before a customer’s legal team blocks your deal, before an investor asks awkward questions, or before you ship something you later have to rebuild.

This guide will help you spot the signs fast. You will learn how “high-risk” labels usually work, what people check first, and how to reduce risk without slowing down product work. If you are building AI in robotics, health, hiring, finance, security, or any tool that touches real people, this matters.

Also, if your advantage is in your model, data flow, sensors, or control system, there is another angle many teams miss: your compliance work can support your IP story. Clear system boundaries, documented methods, and strong technical design choices often become the same “proof” that makes a patent stronger. This is exactly the kind of work Tran.vc supports with up to $50,000 in in-kind patent and IP services for AI and robotics founders. If you want help shaping both the moat and the message, you can apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/.

What “high-risk” usually means (in plain language)

When people say “high-risk AI,” they are not saying your model is evil or unsafe by default. They are saying something more specific:

If your AI can change a person’s life in a serious way, the bar is higher.

That is it. High-risk is less about the algorithm and more about impact. It is about what your system is used for, who it affects, and what could go wrong if it is wrong.

Think of it like this. A movie recommender that guesses your next comedy is wrong sometimes. You shrug and move on. But an AI that helps decide who gets a job interview, who gets a loan, who gets access to a building, or how a robot moves near humans—when those systems are wrong, people can get hurt, locked out, or treated unfairly. That is where “high-risk” language shows up.

You will hear this term in law, in customer procurement checklists, and in investor diligence. Even if you are not selling in a region with strict AI rules, large buyers often follow the strictest standard anyway because it is safer for them. So the practical question is not “Do rules apply to me?” It is: Will my buyer act like they do?

If you sell to banks, hospitals, enterprise HR, defense-adjacent buyers, schools, or cities, assume they will.

The quick test: what does your AI decide, and what does it touch?

Here is a simple way to think about classification without getting lost in legal text. There are two big levers:

1) What the AI decides

Ask: does the AI output affect a decision about a person, their rights, their money, or their safety?

If your AI:

- screens candidates

- ranks students

- scores credit risk

- flags insurance fraud

- supports medical decisions

- controls a robot, vehicle, drone, or device near humans

- decides access to housing, benefits, or services

- drives security checks or identity verification

…you are close to “high-risk” territory in many frameworks.

2) What the AI touches

Ask: is the AI connected to sensitive data or sensitive environments?

If your AI uses:

- health data

- biometric data (face, voice, fingerprints, gait)

- location trails

- data about kids

- data that reveals race, religion, politics, union membership, or similar traits

- data from cameras in public spaces

- data from workplace monitoring tools

…you should assume a higher level of scrutiny.

This is not because you are doing something wrong. It is because the harm from misuse is higher, and because these areas already have rules.

Why founders get surprised by “high-risk” labels

Most founders do not set out to build “high-risk AI.” They build a tool that feels helpful, normal, and practical. Then classification sneaks up on them.

A few common patterns:

The “we are only recommending” trap

A team says, “We do not decide. We just recommend.” But if your customer uses your recommendation as a key input, buyers may still treat you as high-risk. In many real sales cycles, the question becomes: does your tool shape outcomes?

If you rank candidates, even if a human clicks “approve,” you are shaping the outcome.

The “it’s for enterprise” trap

Founders think consumer rules do not apply because they sell B2B. But enterprise tools often trigger the strongest checks. HR, finance, health, and security buyers run the strictest reviews because they are audited.

The “robotics adds weight” trap

If your AI is connected to physical action, classification risk jumps. A vision model that labels images in a lab is one thing. A model that guides a robot arm near workers is different. Physical systems can harm bodies, not just feelings or wallets. That changes everything.

The “we do not store data” trap

Even if you do not store data long term, you may still process sensitive data. That can trigger rules. Also, buyers care about what flows through your system, not only what sits on your servers.

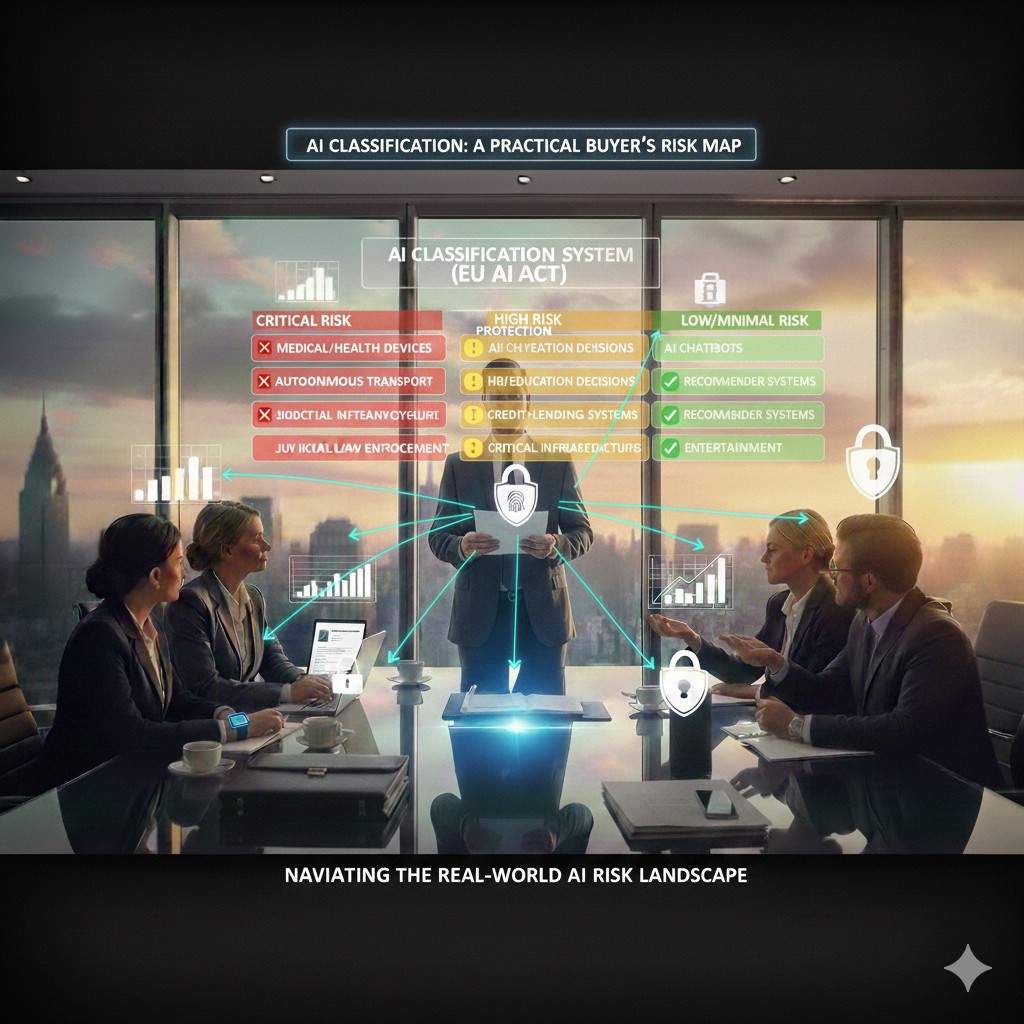

A practical map of risk levels most buyers use

Different laws and standards use different words. But in real life, buyers often act as if there are four levels:

Level 1: low-impact tools

These are tools where mistakes are annoying, not damaging. Think spam filters or AI that helps summarize internal notes.

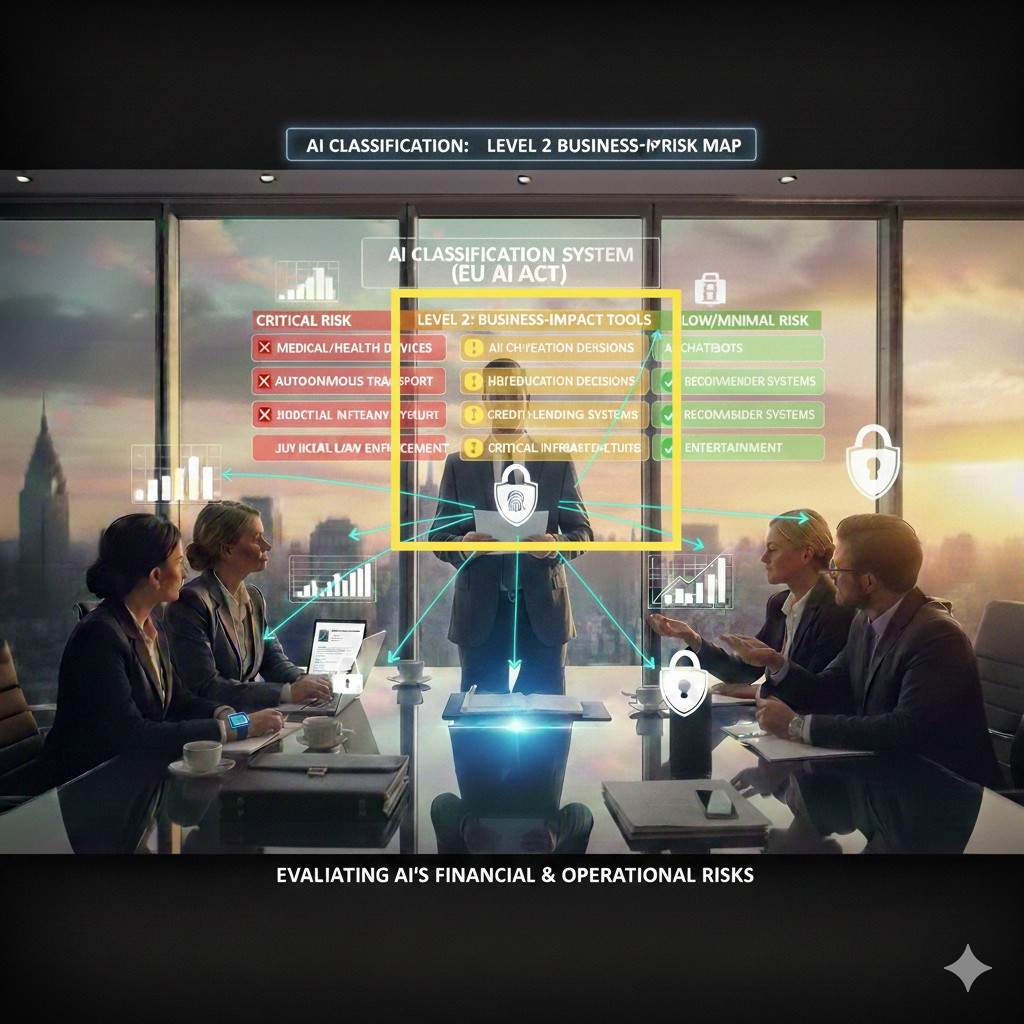

Level 2: business-impact tools

These affect revenue or operations, but not people’s rights or safety. Think demand forecasting for inventory, or routing for delivery trucks (as long as it does not create dangerous driving behavior).

Level 3: people-impact tools

These touch hiring, access, money, education, health, and identity. Mistakes can block a person or treat them unfairly.

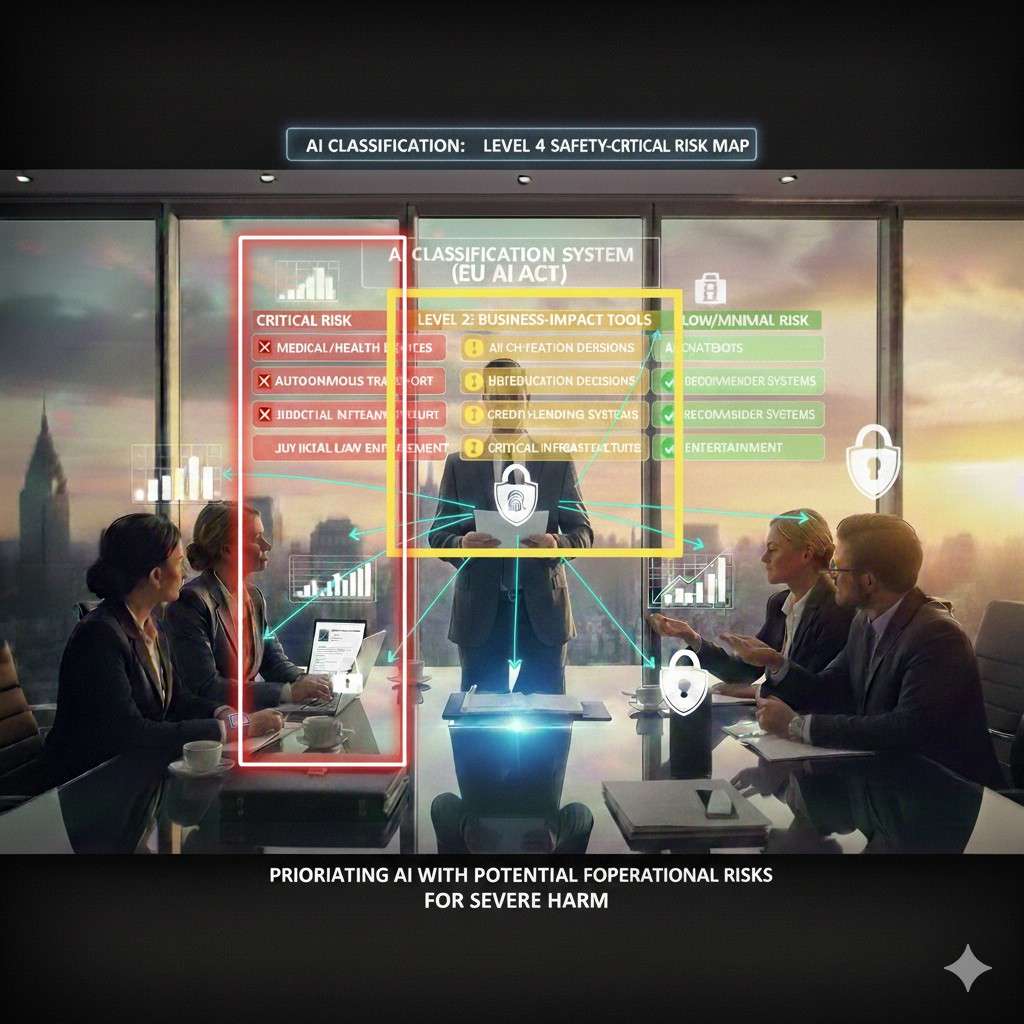

Level 4: safety-critical tools

These can cause physical harm or major damage if wrong. Robotics, vehicles, medical devices, and industrial control systems often land here.

When someone says “high-risk,” they usually mean Level 3 or Level 4.

Now the key point: you can be high-risk even if your model is simple. A basic rules engine that denies benefits can be treated as high-risk. Meanwhile, a deep model that makes playlists is not.

So do not waste time arguing that your model is “just ML.” Buyers do not care. They care what happens when it fails.

The classification questions you should answer on day one

If you want to avoid panic later, write down clear answers to these questions now. Not in legal language. In product language.

What is the exact user action your AI supports?

Not “improves efficiency.” Say what it does: “Ranks candidates for recruiters” or “detects unsafe motion near a robot.”

What happens if it is wrong?

Describe the failure in human terms. “A qualified person gets filtered out.” “A robot moves too close to a worker.” “A patient is flagged incorrectly.”

Who is affected, and how many people?

Risk grows with scale. A tool used on 20 employees is not the same as one used on 2 million applicants.

Is there a path for the person to appeal or correct errors?

Even if you do not control the final process, buyers look for this.

Does the AI replace a step that used to be done by a trained professional?

Replacing a nurse’s triage step or a safety engineer’s check will raise the bar fast.

Is your output used in real time?

Real-time decisions usually mean less chance for human review. That increases risk.

If you cannot answer these questions clearly, classification will feel confusing. If you can answer them, most of the fog disappears.

And if you want help turning these answers into a strong IP and funding story, Tran.vc can help you do that while building your patent strategy and filings. Apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/.

What counts as “high-risk” in the real world (examples founders relate to)

Let’s make it concrete. These examples are not meant to scare you. They are meant to help you recognize patterns.

Hiring and worker tools

If your system screens resumes, scores interviews, predicts performance, monitors productivity, or flags “risk of churn,” many buyers treat it as high-risk. Why? Because jobs are livelihoods. Bias or error here can hurt lives fast.

Finance and insurance

Credit scoring, loan decisions, fraud detection that blocks accounts, insurance pricing, claim approvals—these are almost always treated as high impact. Even when you say “we only assist,” banks will do deep reviews.

Health and wellness

Clinical decision support, triage tools, radiology aids, patient risk prediction, remote monitoring—buyers worry about safety, liability, and compliance. Even “wellness” apps can get pulled into stricter expectations if they influence care choices.

Education and testing

Tools that grade, rank, or place students can shape futures. Schools and regulators pay attention.

Security, identity, and biometrics

Face ID, voice ID, liveness checks, risk scoring for access control—these areas often face strict rules and strong public concern.

Robotics and physical systems

Navigation, control, human detection, collision avoidance, safety monitoring—if the AI can move something heavy, sharp, or fast, treat it as high-risk by default. Even if the AI is not the safety layer, buyers may still ask for evidence that it is safe.

If your product lives in these zones, do not wait for a buyer to label you. Do the work early so you can respond with confidence.

The fastest way to reduce “high-risk” pain: define boundaries

A lot of “high-risk” stress comes from fuzzy boundaries. The more vague your product claim, the more scary it sounds to a compliance team. But if you define the system boundary clearly, you often reduce perceived risk.

This is one of the most tactical steps you can take:

Write one paragraph that says what your AI does and does not do.

Example (not for you to copy, just to see the pattern):

“Our system detects humans near an industrial robot and sends an alert to the operator. It does not control robot motion. It does not make employment decisions. It does not identify individuals.”

Notice what that does. It reduces the threat surface. It also makes your IP clearer: you can patent the detection and alert method without claiming things you do not do.

When Tran.vc works with founders, this kind of boundary work often becomes part of the patent plan. You end up with cleaner claims, fewer surprises in diligence, and a stronger story for investors. If that sounds useful, apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/.

The main ways “high-risk” gets defined

Three forces shape the label

Most founders think “high-risk” is one single rule. In real life, it comes from three places at once: laws, buyer checklists, and public safety norms. These three often overlap, but they do not always match.

Laws set the floor. Big buyers set the bar higher than the law. And safety norms shape what people accept, even if no one is suing yet.

Laws focus on impact, not model type

Many modern AI rules do not care if you use deep learning, a small model, or even basic scoring. They care about the outcome. If your AI can change access to work, money, health, or safety, it attracts more rules.

That is why a “simple” ranking tool in hiring can get more scrutiny than a complex model that only tags photos for fun.

Buyers focus on liability and audit trails

A large customer is thinking about audits, lawsuits, and brand risk. They will ask: can we explain what this system does, prove we tested it, and show we can control it?

Even if the law is light in their region, global companies often apply strict checks everywhere. It is easier for them to run one standard than ten.

Safety norms focus on physical harm and fairness

Robotics, drones, and medical tools trigger a different kind of concern because harm can be immediate. Hiring, education, and finance trigger concern because harm can be unfair and hard to undo.

This is where “high-risk” becomes a social label, not just a legal one. If the public would feel uneasy about your use case, your buyer will feel that pressure too.

The two big “high-risk” buckets you must separate

People-outcome systems

This bucket is about systems that shape a person’s future. The classic examples are hiring, lending, admissions, benefits, and insurance decisions.

Even if your tool only “supports” the decision, it still shapes who gets seen, who gets filtered, and who gets delayed. The risk here is not only errors. It is also uneven impact across groups.

Safety-outcome systems

This bucket is about systems that can lead to physical harm or major property damage. Robotics, industrial systems, vehicles, medical devices, and critical infrastructure often fall here.

The risk here is not mainly bias. It is unsafe behavior, edge cases, weak monitoring, and failures in the real world where conditions are messy.

Why this distinction changes your plan

If you mix these buckets, you will build the wrong controls. A hiring tool needs strong fairness checks, clear human review steps, and clean record keeping around decisions.

A robotics tool needs strong testing, fail-safe behavior, clear limits, and constant monitoring in live settings.

Both can be “high-risk,” but the work you do to prove trust is different.

What “high-risk” usually triggers in a buyer review

Stronger questions during procurement

Once a buyer flags you as high-risk, the tone of the review changes. They stop asking “does it work” and start asking “can we defend it.”

They will want to see what data you use, how you tested the system, what happens when it fails, and how a human can override it.

More demand for clear system boundaries

High-risk reviews punish vague claims. If your website says “automates hiring,” a buyer will assume the worst-case meaning.

If you say “helps recruiters sort applicants, with human review required,” you give them a safer story. Clear boundaries reduce fear, and fear is what slows deals.

Pressure to document decisions early

High-risk systems often need a paper trail. Buyers will ask for records of changes, model versions, test results, and user actions.

If you build this late, it feels painful. If you build it early, it becomes normal product work.

A hidden bonus for IP and fundraising

This may sound surprising, but the same clarity that makes compliance easier can make your IP stronger. When you can explain your system cleanly, you can also claim it cleanly.

Tran.vc helps founders turn this work into patents and defensible assets, not just paperwork. If you want support with strategy and filings, you can apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/.

A fast, practical classification method you can run today

Step one: write the “use” sentence

Start with one sentence that is plain and strict. Not marketing. Not dreams. Just the use.

For example: “Our model flags unsafe worker-robot proximity in real time.” Or: “Our model ranks loan applicants for manual review.”

This sentence is your anchor. If you cannot write it, classification will stay fuzzy.

Step two: name the affected person

Now write who can be harmed if the system is wrong. Use real words, not categories.

Is it a worker on a factory floor? A patient in a clinic? A job applicant? A student? A tenant? A driver? The more direct the harm, the higher the risk.

This step matters because many founders only think about the customer, not the person affected by the system’s output.

Step three: describe the worst reasonable failure

Do not imagine a fantasy disaster. Imagine a real failure you could see in the next year.

Could your system block access to income? Could it cause unsafe motion? Could it label a person incorrectly? Could it expose private data?

If your worst failure involves physical injury, loss of a job chance, denial of a service, or identity misuse, treat the system as high-risk until proven otherwise.

Step four: check whether humans can truly intervene

Founders often say “a human is in the loop,” but buyers ask a deeper question: can the human realistically disagree?

If your system produces a score and the team follows it 95% of the time, that is close to automation in practice. If your system runs in real time, the human may not have time to stop it.

This is not a moral judgment. It is a reality check. The less real control humans have, the higher the risk level feels.

Step five: place yourself in the right bucket

Now decide which bucket is the better match: people-outcome or safety-outcome. Some products touch both, but most have a clear center.

If you are in the people-outcome bucket, focus on fairness, explainability, and decision traceability. If you are in the safety-outcome bucket, focus on testing, fail-safe design, monitoring, and strong limits.

This simple choice prevents you from wasting months building the wrong kind of “trust work.”

High-risk versus “sensitive” is not the same thing

Sensitive data can exist in low-risk tools

A tool can process sensitive data and still be low-impact, depending on the use. For example, an internal tool that summarizes doctor notes for a clinician might be less risky than a tool that decides who gets care.

But sensitive data still raises privacy duties, security standards, and buyer concern. So “not high-risk” does not mean “no work needed.”

High-risk can exist with normal data

The reverse is also true. A hiring system can be high-risk even if it only uses work history and skills.

The risk comes from the decision power, not the privacy level. This is why classification must start with “what does it decide,” not “what data do we store.”

Why you should separate these in your messaging

In sales calls, it helps to keep these topics separate. One is about impact and decision power. The other is about data duties.

When you mix them, you confuse buyers. When you separate them, you sound mature and prepared.

The most common confusion: “assistive” versus “decision” AI

Assistive systems reduce work, but still guide outcomes

Many AI tools begin as assistants. They draft notes, summarize calls, flag cases, or suggest next steps.

These feel safer, but they can still become high-risk if the assistant’s output becomes the real driver of action. Over time, teams rely on it. Shortcuts form. Human review becomes a formality.

So the question is not what you intended. It is what happens in real use.

Decision systems set direction and narrow options

A decision system does not need to say “approve” or “deny.” It can “decide” by narrowing the list.

If your AI ranks candidates and the recruiter only looks at the top 20, you have shaped access. If your AI flags “high fraud risk” and accounts get frozen, you have shaped rights and money.

This is why many buyers treat ranking and scoring as decision-like behavior, even when you do not call it that.

How to design your product to stay clearly assistive

If you want to stay on the assistive side, you need product choices that prove it. Clear prompts for review, obvious ways to override, and logs that show human action.

It is also helpful to avoid language like “auto-approve” and to avoid default settings that make the AI output feel final.

If you want help shaping these boundaries in a way that also strengthens patents and your investor story, Tran.vc can help. Apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/.