Open source feels like a gift. You pull a library, ship faster, and move on.

AI feels like magic. You plug in a model, fine-tune it, and suddenly your product works.

But when you mix open source and AI, you also mix two things that can quietly break your IP story. Not with a loud failure. With a slow leak that shows up later—during fundraising, a customer security review, or a patent filing—when someone asks a simple question:

“Do you actually own the right to do this?”

That’s the moment many strong technical teams get stuck.

This article is about avoiding that moment.

It is not here to scare you away from open source. And it is not here to tell you to “patent everything.” Open source is a tool. Patents are a tool. The problem is not the tool. The problem is stepping on a hidden rule you did not know was there.

Think of IP landmines like this: you can do everything “right” from an engineering view, and still create a legal mess. Not because you had bad intent. Because you moved fast, copied a snippet, trained a model on a dataset you did not fully check, or used a library with a license that did not match your plan.

A lot of founders learn this late. You do not need to.

At Tran.vc, we work with robotics, AI, and deep tech founders early, when the code is still fresh and the product is still flexible. We invest up to $50,000 in kind as patent and IP services, so you can build a real moat without rushing into a priced round too soon. If you want help building a clean IP plan from day one, you can apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/.

Now, let’s start with the first “landmine” most teams hit: thinking open source is “free.”

Open source is not one thing. It is many licenses. Each license is a set of promises and rules. Some are easy. Some are strict. Some are risky for startups that want to sell software, build closed products, or file patents.

Here is the part most people miss: open source risk is not only about lawsuits. The bigger risk is that open source can force you to share your own code, or block a clean patent story, or make an acquirer nervous. That can slow down a deal. It can change a valuation. It can kill a partnership.

And it often starts small. A single dependency. A “tiny” utility file. A copy-pasted function from a repo. A model checkpoint pulled from a random link. A dataset from a blog post with unclear terms.

You can build a whole company on top of that without noticing.

So the right mindset is not “avoid open source.” The right mindset is “use open source with eyes open.”

If your startup is B2B, your buyers will ask about this. If you raise from serious investors, they will ask too. If you ever want to patent your AI system, your patent counsel will ask. If you want to sell the company, diligence will ask in painful detail.

Let’s talk about the three ways open source and AI collide in a way that creates IP landmines.

First is the code you ship.

Second is the data you touch.

Third is the model you use or train.

Code is the one founders think about first. Data and models are where the surprises live.

On the code side, the biggest trap is using a license that pulls your closed source product into the open. People call this “copyleft,” but you do not need that word. You just need the idea.

Some licenses say: “You can use this code, but if you ship a product that includes it in certain ways, you must also share your own source code under the same license.”

If you are building a paid product, that might not fit. If you are building a robotics stack that you want to keep private, it might not fit. If your whole value is in your training loop, control system, or edge inference code, it might not fit.

The second code trap is mixing licenses without realizing it. Engineers do not do this on purpose. It happens because modern software is a web of dependencies. A single package can pull in fifty more. Each can have its own license. Your repo can be clean while your build is not.

The third code trap is forgetting patents exist inside open source licenses. Many modern open source licenses include patent language. That language can help you, or hurt you, depending on your plan.

This is where AI patents come in.

If you want to patent your AI invention, you must show novelty. You must show what is new and not obvious. If your “new” method is mostly a known open source method with small changes, that is already a weak story. But there is a second issue: if your work is built on code under a license that contains patent clauses, you might be giving away rights without meaning to.

Also, if you contribute back to some projects, you might be granting patent rights to users of that project. Again, not always bad. But it must be a choice, not an accident.

Now, the data side.

Many AI teams treat data like air. They breathe it in. They forget it is owned by someone. Or governed by terms.

You can train on a dataset and never ship the dataset. You still can have trouble if the dataset terms do not allow your use. In some cases, you can also create issues if the data has personal info, or if it comes from sources that have “no scraping” rules, or if it includes content that is not licensed for model training.

This is why “open data” is as messy as open source.

Some datasets are truly open. Some are open for research only. Some allow commercial use but require credit. Some block certain uses. Some are silent, which is not a green light. Silence is risk.

For robotics and AI startups, the data problem can show up in ways that feel unfair. A founder will say, “We collected the data ourselves.” But the data may include customer environments, faces, voices, factory layouts, machine telemetry, or sensor feeds from hardware that has its own terms. If you do not paper this early, it can limit what you can patent, what you can sell, and what you can claim you own.

Now, the model side.

Models come with terms too. Some models are “open weights” but not fully open. Some allow use but block certain industries. Some allow research but block commercial use. Some force you to share changes. Some require you to add a notice. Some require you to pass along the same rules to your users.

The big mistake is assuming that “downloadable” means “free to use any way.”

It does not.

And when you train or fine-tune, you add a new layer. Your trained model may be a “derivative” under some rules. Or it may carry obligations. Or it may be hard to prove it is clean if you cannot show what went into it.

This is where investors get nervous. Not because they hate open source. They love it. But because they hate uncertainty.

So what do you do, in a practical way, when you are a startup moving fast?

You build a simple system that keeps you out of trouble. Not a heavy process. Not legal overhead that slows shipping. A lightweight habit.

Start by making a clear map of what is “yours.”

This sounds obvious, but most early teams cannot answer it cleanly.

What parts are your code? What parts are borrowed? What parts are generated? What parts come from contractors? What parts come from previous employers? What parts come from open source?

If you cannot draw that line, you cannot protect your value.

A clean map helps with patents too. When you file, you need to show who invented what and when. You need to show what is novel. You need to avoid putting other people’s licensed code into your core claims.

Next, decide what you will never do.

A strong team has a few hard rules.

For example, some teams decide they will not paste code from random repos into production. They will only pull code through approved packages, so licenses can be tracked.

Some teams decide they will not train on datasets unless they can save the license terms in the repo.

Some teams decide they will not use “open weights” models unless commercial use is clearly allowed.

These are not big lists. They are few rules that prevent big pain.

Then, track your dependencies like you track security bugs.

If you already use a tool that scans for security issues, add license scanning to the same routine. If you do not, you can still do it with a basic check in your CI. The goal is not perfection. The goal is spotting the one risky license early, before it spreads.

Also, treat prompts and training data like you treat source code.

Keep a record of where they came from. Keep a record of what rights you have. Keep a record of what you promised to customers.

This helps when you want to file patents. It helps when a buyer asks. It helps when a customer asks for proof you are not training on their private data.

Finally, build your patent plan around what is truly your invention.

A lot of AI patents fail because they are too broad and too generic. Or because they read like a blog post on “use a neural net for X.” That is not strong.

Strong AI patents usually focus on the engineering reality: how you make it work in a real system. How you handle edge cases. How you reduce compute. How you deal with drift. How you do safety checks. How you combine sensors. How you keep latency low. How you control a robot safely. How you validate outputs. How you improve accuracy without leaking data.

Those are often the parts teams actually invent.

And those are often the parts that are safest from open source landmines, because they are specific to your stack, your pipeline, your product.

This is exactly where Tran.vc helps founders. We help you identify the few core inventions that matter, and we turn them into assets investors respect. We do it early, with real patent attorneys, and with a strategy that fits how startups really build. If you want that kind of help, apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/.

Open Source Code: Where Most IP Problems Begin

The “Free Code” Myth That Hurts Startups

Open source can feel like a shortcut you earned. You did the work to find it, test it, and wire it into your product, so it feels “yours” in practice.

But open source is not a gift with no strings. It is a trade. You get speed, and in return you follow the rules of the license. Those rules are not moral rules. They are legal rules. And legal rules do not care that you were in a rush.

Most IP trouble starts because the team thought open source meant “public,” and public meant “safe.” That is not how it works. A repo can be public and still have strict limits on what you can do with it.

Permissive Licenses: Usually Safe, Still Not Automatic

Some licenses are designed to make reuse easy. They often let you use the code in a paid product, change it, and keep your own code private.

This is why many startups feel relaxed once they hear “MIT” or “Apache.” In many cases, that relaxed feeling is fair. But even “easy” licenses still carry duties, like keeping notices and credit lines, or including the license text in certain places.

The landmine here is not that you will lose your company overnight. The landmine is diligence. If you cannot prove you followed the basic duties, an investor or buyer may treat it as sloppy controls. And sloppy controls around IP can slow a deal more than most founders expect.

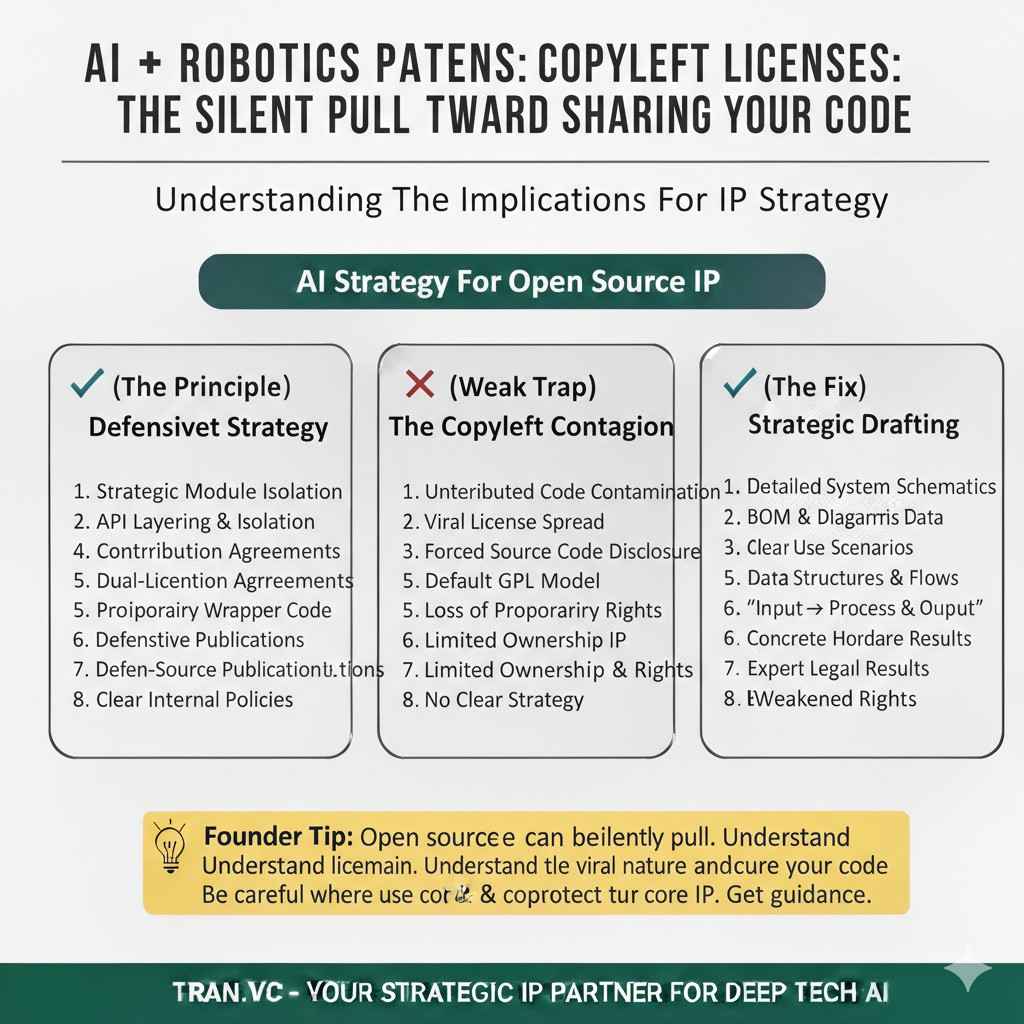

Copyleft Licenses: The Silent Pull Toward Sharing Your Code

Other licenses come with a different trade. They say you can use the code, but if you ship software in certain ways, you may need to share your own source code under the same terms.

Teams run into trouble when they discover this after the product is already built. By that time, the dependency is not a small part. It is stitched into the system. Replacing it can take weeks, sometimes months, and it can introduce bugs at the worst moment.

If your plan is to keep your core product closed, you must treat strong copyleft licenses like a bright warning sign. It does not mean “never.” It means “only if we are fully aware and fully aligned.”

Hidden Dependencies: The Risk You Did Not Intend to Take

Even careful teams can get burned because they only check what they directly imported. Modern software pulls in other packages behind the scenes.

A single dependency can bring a tree of sub-dependencies. Some will be harmless. One might not be. If that one risky license is in your build, you now carry it too, even if you never typed its name.

The fix is not heavy legal review of every line. The fix is visibility. You want a clear inventory of what your build includes, so you can spot problems early, while the cost to change is still small.

Copy-Paste Code: The Most Common “Accidental Contamination”

The most dangerous open source is the code that never gets tracked as open source. This happens when someone copies a snippet from a repo, a gist, a blog, or a Stack Overflow answer, and pastes it into production.

It feels harmless because it is small. But small code can still be protected. Small code can still have a license. And small code can still create duties you did not follow, because you did not record where it came from.

If you want one simple habit that prevents a lot of pain, it is this: treat copy-paste like importing a dependency. If you bring it in, you log it. If you cannot log it, you rewrite it.

Patent Clauses Inside Licenses: The Part Many Founders Miss

Some open source licenses include patent language. This can be good, because it can protect you from patent threats by contributors.

It can also matter if you plan to file patents yourself. In some setups, certain actions, like filing a patent claim against users of a licensed project, can trigger consequences under the license terms.

Most founders never plan to sue anyone. The bigger point is cleaner: you do not want to accidentally give away patent rights, or create a conflict between your patent strategy and your license duties.

When you know this early, you can design around it. When you learn it late, you end up negotiating with your own past decisions.

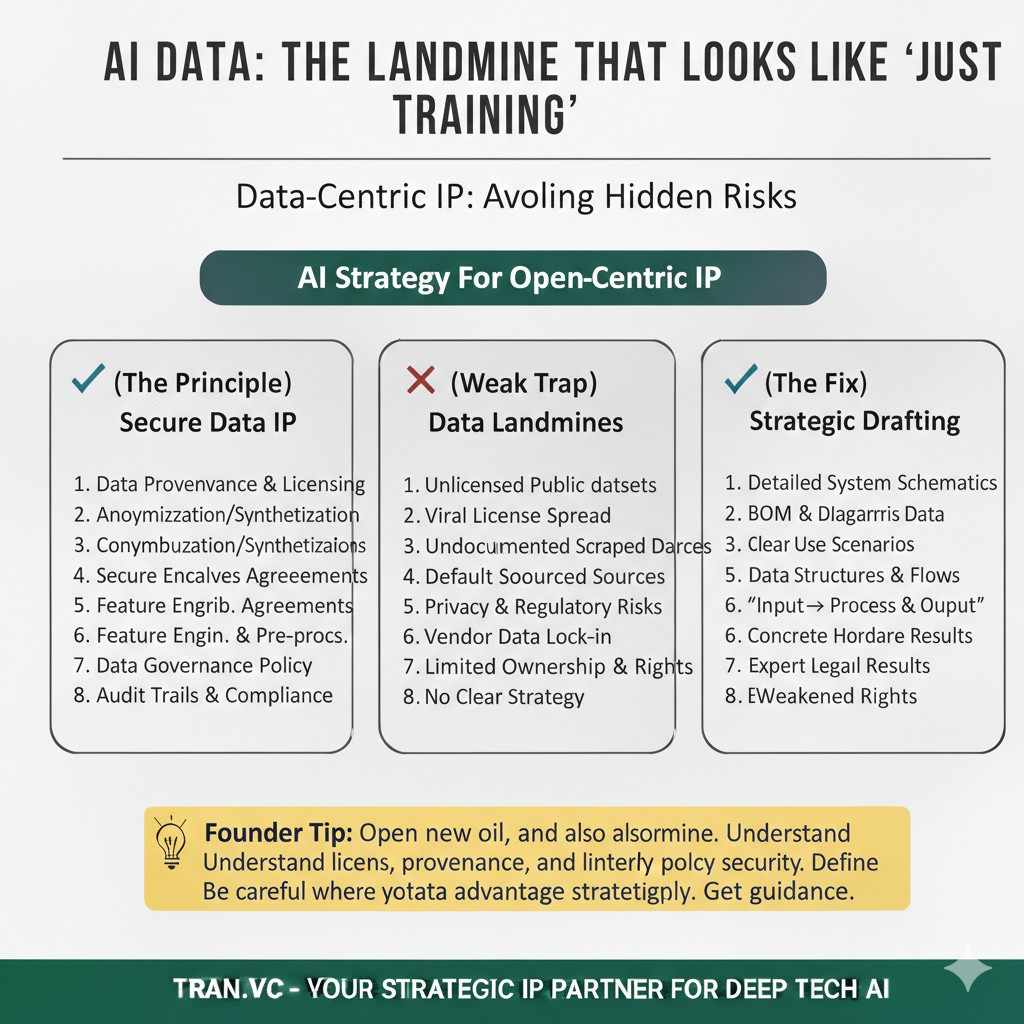

AI Data: The Landmine That Looks Like “Just Training”

“We Don’t Ship the Data” Is Not a Defense

Many teams assume that if they never deliver the dataset to customers, then the dataset does not matter.

But training is still a use. If the dataset terms do not allow that use, you can still face risk. The risk may show up as a takedown request, a breach claim, a customer concern, or a blocked partnership.

Even if the risk never becomes a lawsuit, it can still become a trust problem. If your buyer asks where your model learned its behavior, you need an answer that is calm and clear.

Open Datasets: “Open” Often Means “Open for Research”

A dataset can be “open” in the casual sense, meaning easy to download. That does not always mean it is open for commercial use.

Some datasets are shared for research, and the terms can block paid use, or require special approvals. Some require credit. Some block use in certain products. Some do not say anything, which is not permission.

The landmine is not just the terms. The landmine is your lack of records. If you cannot show the dataset terms you relied on at the time, you will struggle to prove your use was allowed.

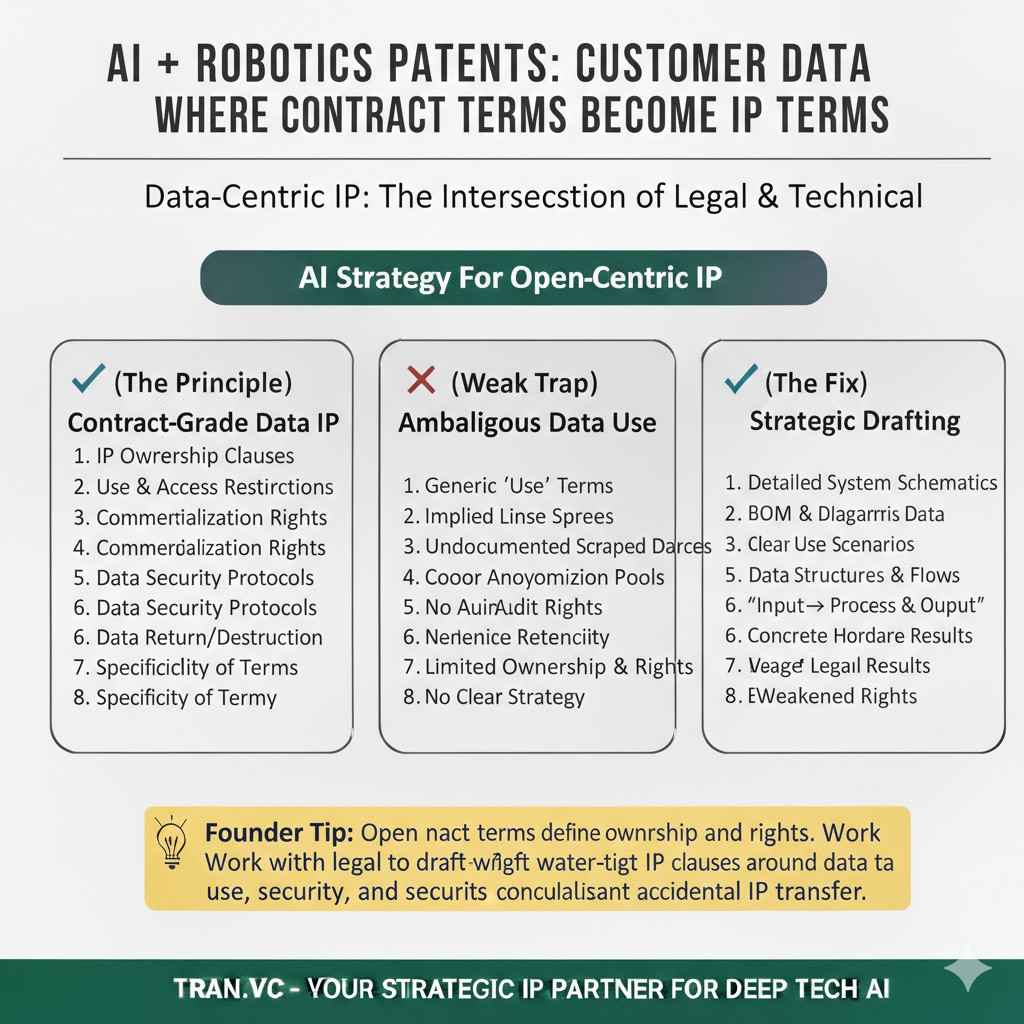

Customer Data: Where Contract Terms Become IP Terms

In B2B, your best data often comes from customers. That is normal and healthy. But it only stays healthy if the contract is clear about what you can do with the data.

If you collect logs, sensor feeds, or images from a factory floor, you must know whether you can train on it. You must know whether you can use it to improve a shared model across customers. You must know whether you can use it to build a patent story.

If you are not careful, you end up with a model that depends on data you are not allowed to use long-term. That can trap your roadmap in a way that is painful to unwind.

Scraped Data: Easy to Gather, Hard to Defend

Scraping can feel like a fast way to bootstrap a dataset. But it is also where AI teams run into rules they did not anticipate.

Sites often have terms that block scraping or reuse. Some content is protected. Some content includes personal information. Even if you do not intend harm, your collection method can be questioned.

If your company is built on scraped data, you need a plan that stands up to scrutiny. “Everyone does it” is not a plan that passes diligence. A clean permission path, a clean source list, and a clean risk review is.

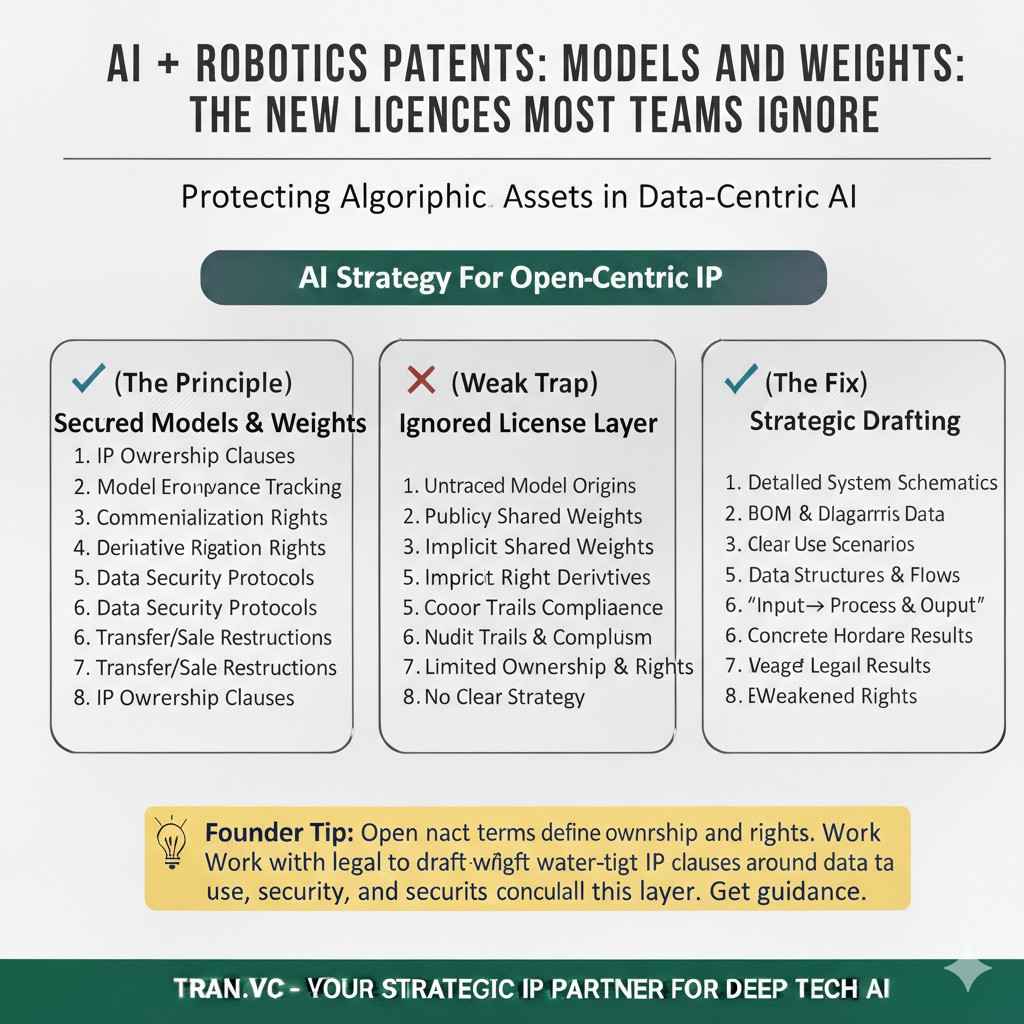

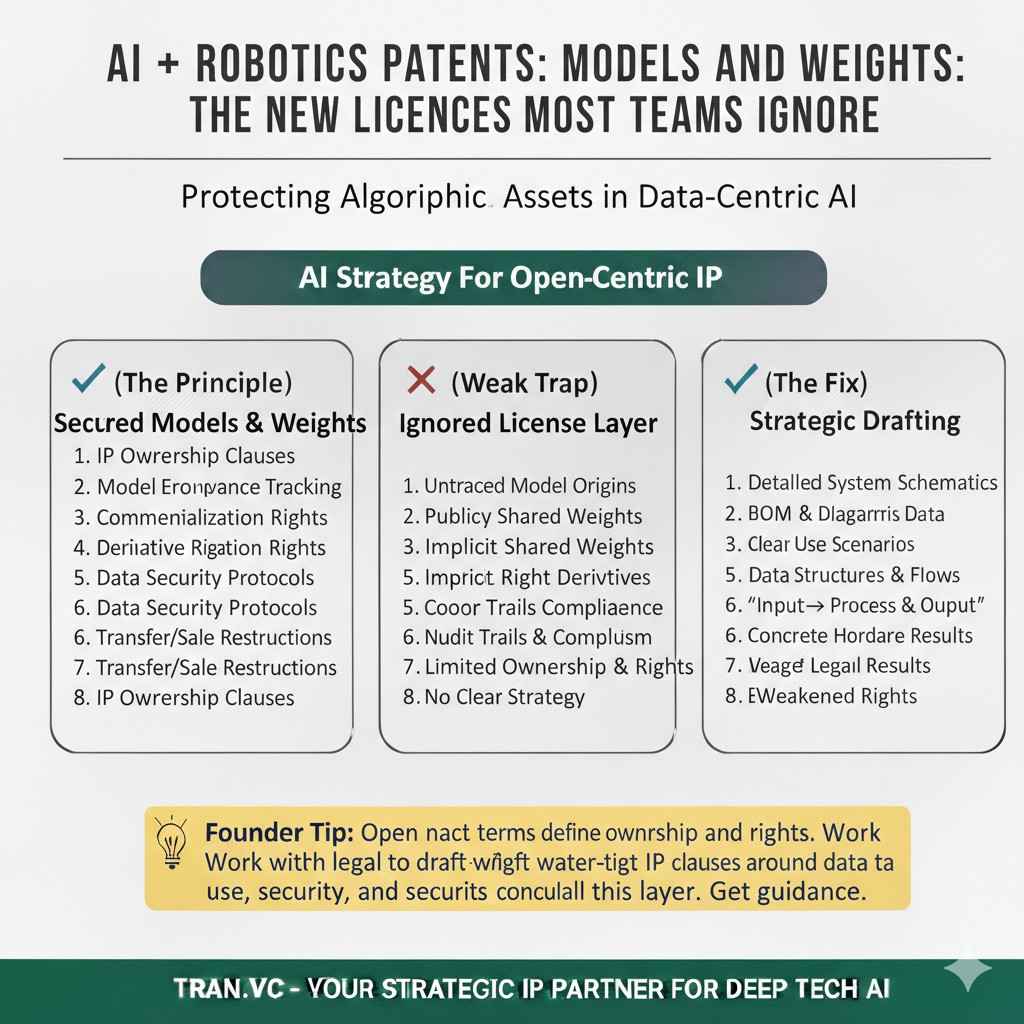

Models and Weights: The New License Layer Most Teams Ignore

“Open Weights” Is Not the Same as “Open Source”

Many modern AI models are shared with weights that can be downloaded. Some teams assume that means they are free to use however they want.

But “open weights” can come with use limits. Some allow commercial use, some do not. Some block certain industries. Some require you to pass terms down to your users.

If your product depends on a model with terms that conflict with your sales model, you can get stuck later. It is far cheaper to check early than to replace a model after customers depend on it.

Fine-Tuning and Derivatives: When Your Work Inherits Duties

When you fine-tune a model, you are not starting from zero. You are building on top of someone else’s work.

Some licenses treat fine-tuned models as derivatives. That can mean your fine-tuned weights must follow certain terms too. If you planned to keep your tuned model private, that can become a problem.

This is why it matters to check license terms before you invest a month into training. Training cost is not just GPU cost. It is also the cost of becoming dependent on something you cannot later control.

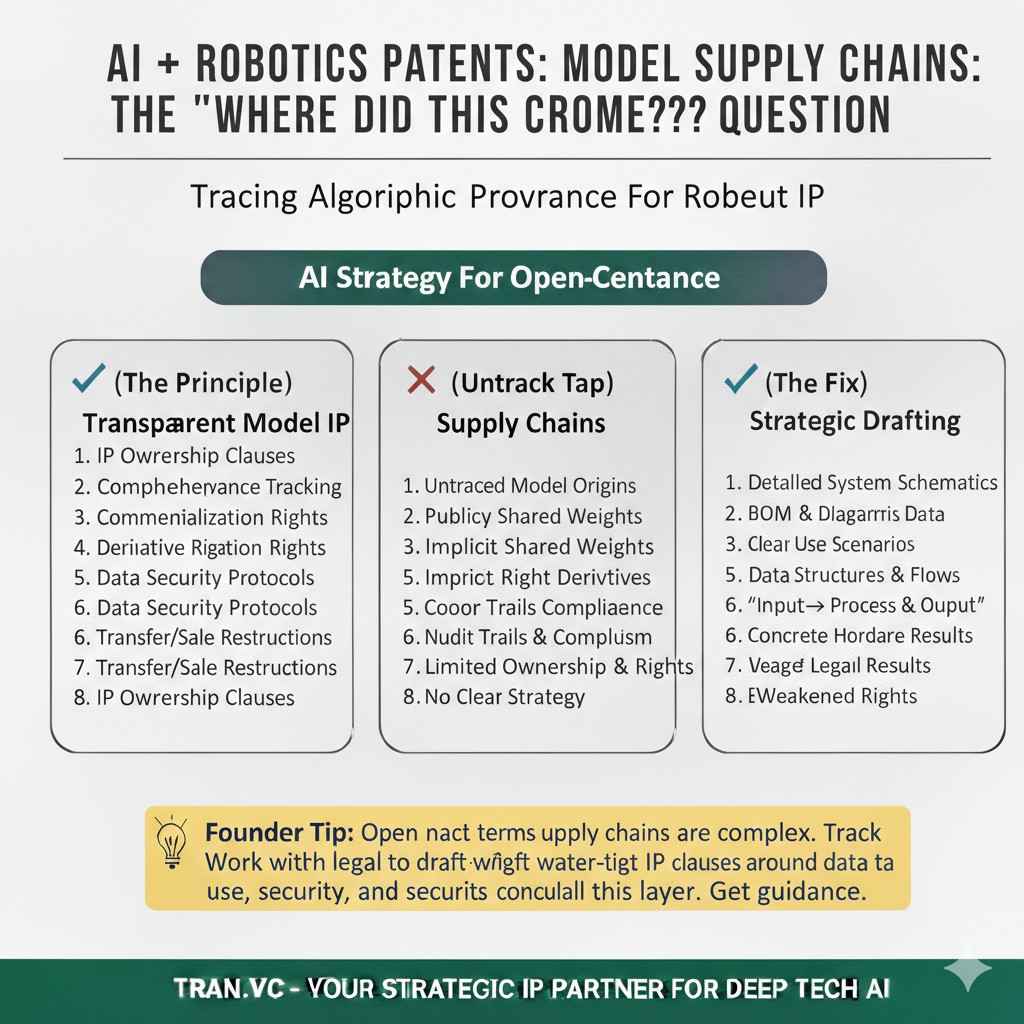

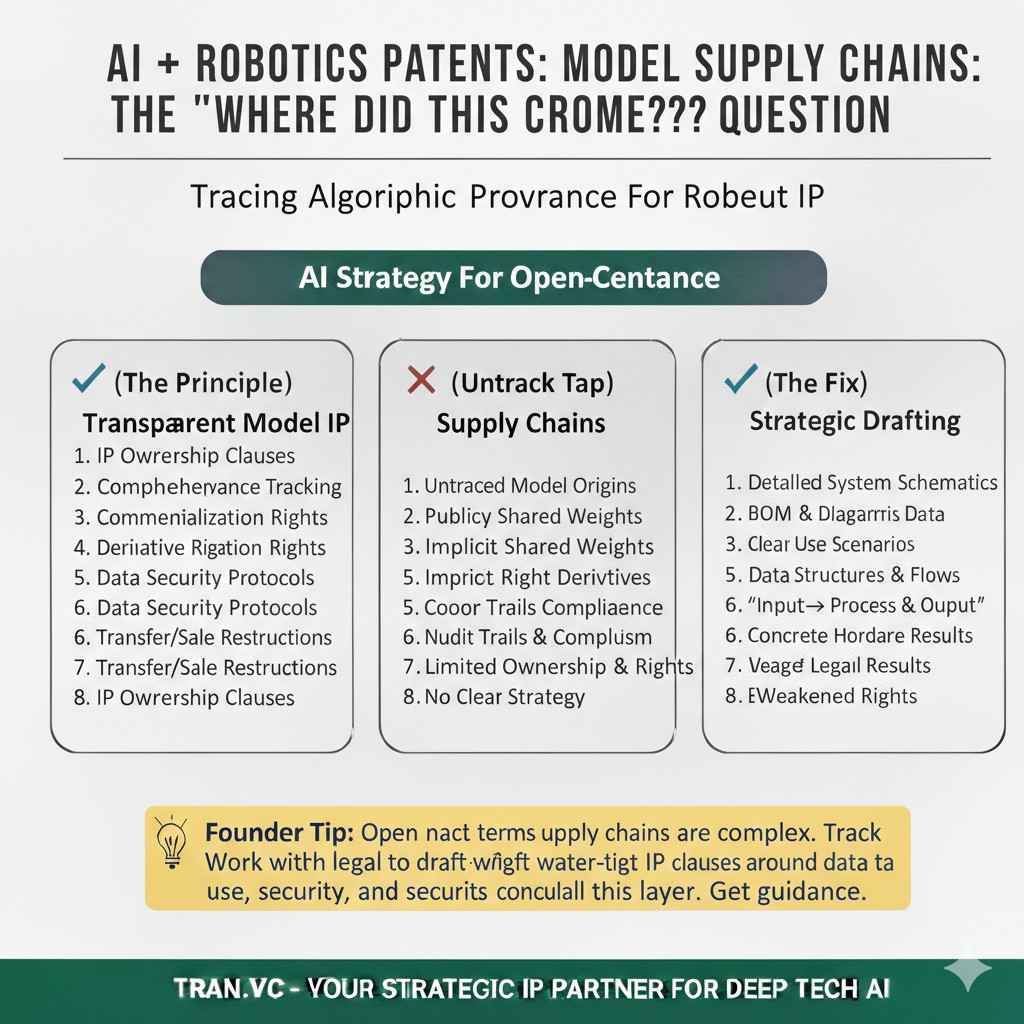

Model Supply Chains: The “Where Did This Come From?” Question

If you use a model checkpoint from a random source, you may not know what data it was trained on, what rights were secured, or whether it contains restricted material.

This is not only a legal issue. It is also a business issue. Regulated buyers, large enterprises, and security teams will ask about provenance and controls.

When you can answer with confidence, you look mature. When you cannot, you look risky, even if your tech is strong.

Patents in the Middle of All This: How to Keep Your Claims Clean

Patents Reward What You Truly Invent, Not What You Assembled

A strong patent story is not “we used a model to do X.” That is usually too broad and too common.

Strong AI and robotics patents tend to focus on the hard parts. The parts you built because the off-the-shelf approach failed. The parts that made it work in real conditions, with real limits, and real users.

This matters for IP landmines too. If your “core invention” is mostly a licensed method, your patent may be weak. If your invention is your unique pipeline, control logic, safety checks, or efficiency tricks, you are often on safer ground.

The Clean Room Mindset for IP: Prove What Is Yours

You do not need to behave like a giant company. But you do need one simple discipline: keep proof of what is yours.

That means documenting internal invention steps, tracking major design choices, and recording where you used third-party code, data, or models. It means having a clear boundary between what you created and what you borrowed.

When you do this, patents become easier. Fundraising becomes easier. Customer diligence becomes easier. You stop relying on hope.

Where Tran.vc Fits: Early IP Work That Makes Later Rounds Easier

This is exactly the phase where Tran.vc helps. Not once you are already tangled, but early, while the system is still flexible.

Tran.vc invests up to $50,000 in-kind as patent and IP services. That includes strategy and filings with real patent attorneys, aimed at turning your actual technical edge into defensible assets.

If you are building robotics, AI, or deep tech and you want to avoid these landmines while building a real moat, you can apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/.

If you are building robotics, AI, or deep tech and you want to avoid these landmines while building a real moat, you can apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/.