If you build in AI, robotics, or other deep tech, you are probably sitting on something valuable—even if it still feels rough. A patent can turn that “rough” idea into a real business asset. Not a trophy. Not a vanity thing. An asset that can block copycats, raise your value in a fundraise, and make buyers and partners take you seriously.

But here is the hard part: most founders don’t lose patents because their tech is “not good enough.” They lose because they describe it in the wrong way, at the wrong time, with the wrong proof.

This guide is here to fix that. We’ll walk through what “patentable” really means for deep tech, how examiners think, what usually kills an application, and how you can shape your invention so it has a real shot—without turning your brain into legal soup.

Also, if you want hands-on help: Tran.vc invests up to $50,000 in in-kind patent and IP services for AI, robotics, and other technical startups. You can apply anytime here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

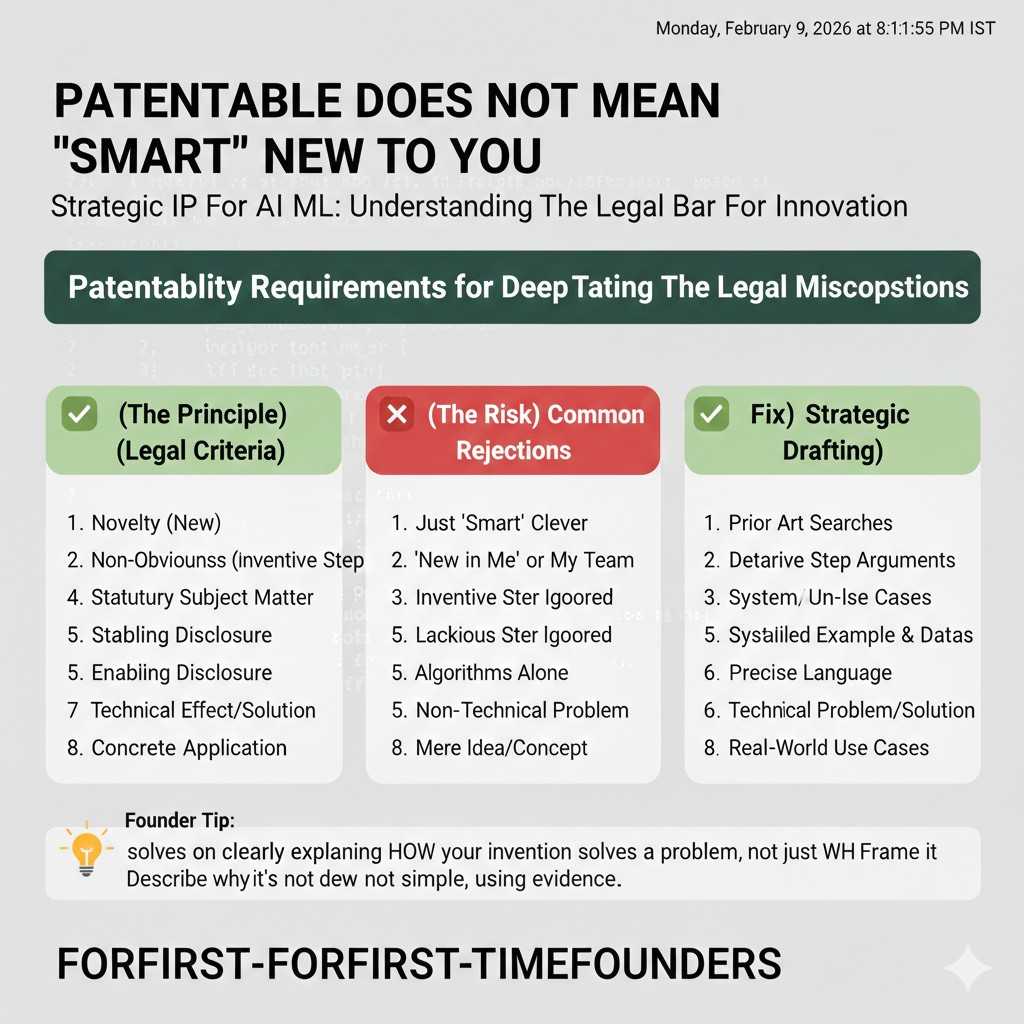

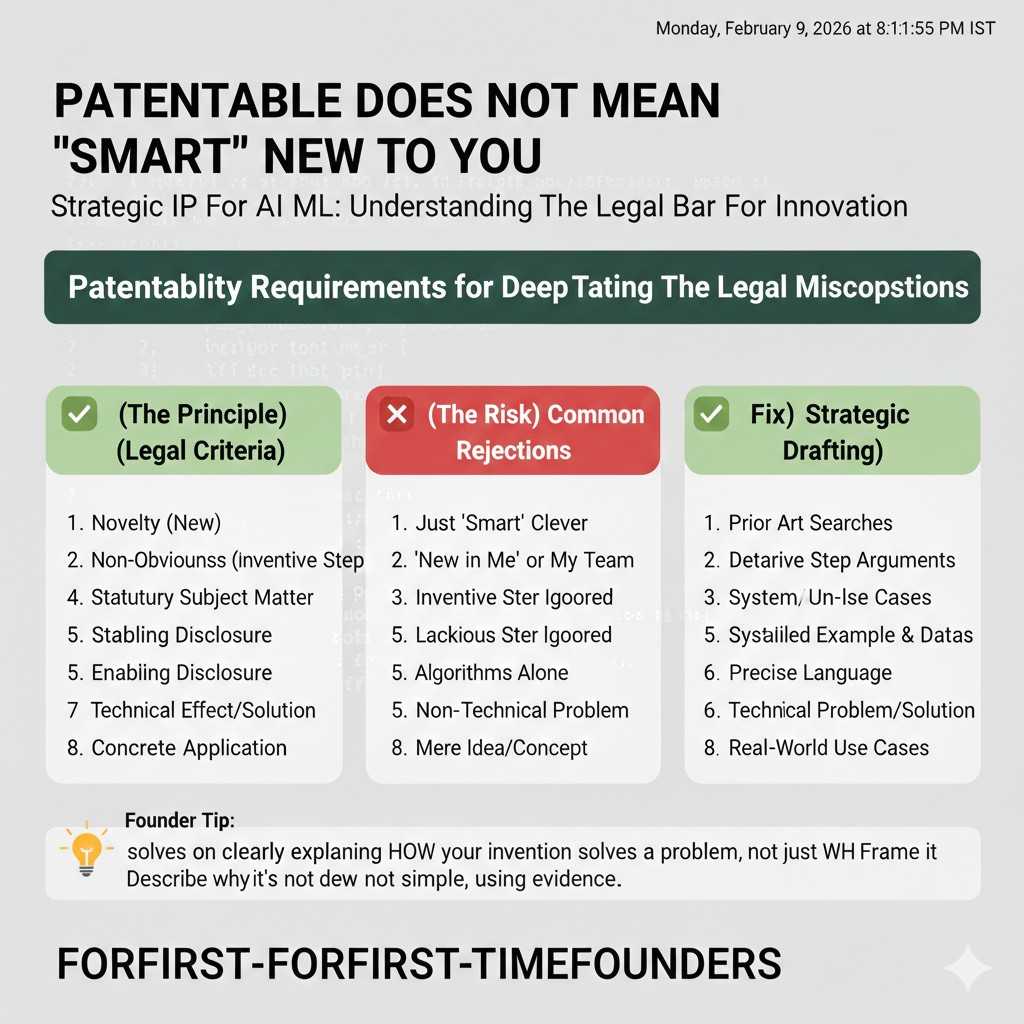

Patentable does not mean “smart” or “new to you”

Let’s start with a simple truth that surprises a lot of technical teams:

Your invention can be brilliant and still not be patentable.

Patents are not awards for being clever. A patent is a trade with the public. You disclose how your invention works. In return, the government gives you a time-limited right to stop others from making or using what you claimed.

So the test is not “Is it impressive?” The test is closer to:

- Is it new compared to what already exists in public?

- Is it not an obvious next step from what already exists?

- Is it described clearly enough that someone skilled in the field could build it?

- Is it the kind of thing the law allows patents on?

Those are the core ideas. The details matter a lot in deep tech, because AI and robotics inventions often look “abstract” at first glance. And “abstract” is where patent applications go to die if they are not written well.

A deep tech invention becomes patentable when you can explain it as a concrete system that solves a concrete technical problem, in a way that is different from what people already showed publicly.

That sounds simple. In real life, it takes discipline.

The four gates your invention must pass

Most patent systems (including the U.S.) focus on a few key requirements. The words used in the law can feel stiff, but the ideas behind them are practical. Think of them as gates your invention must pass.

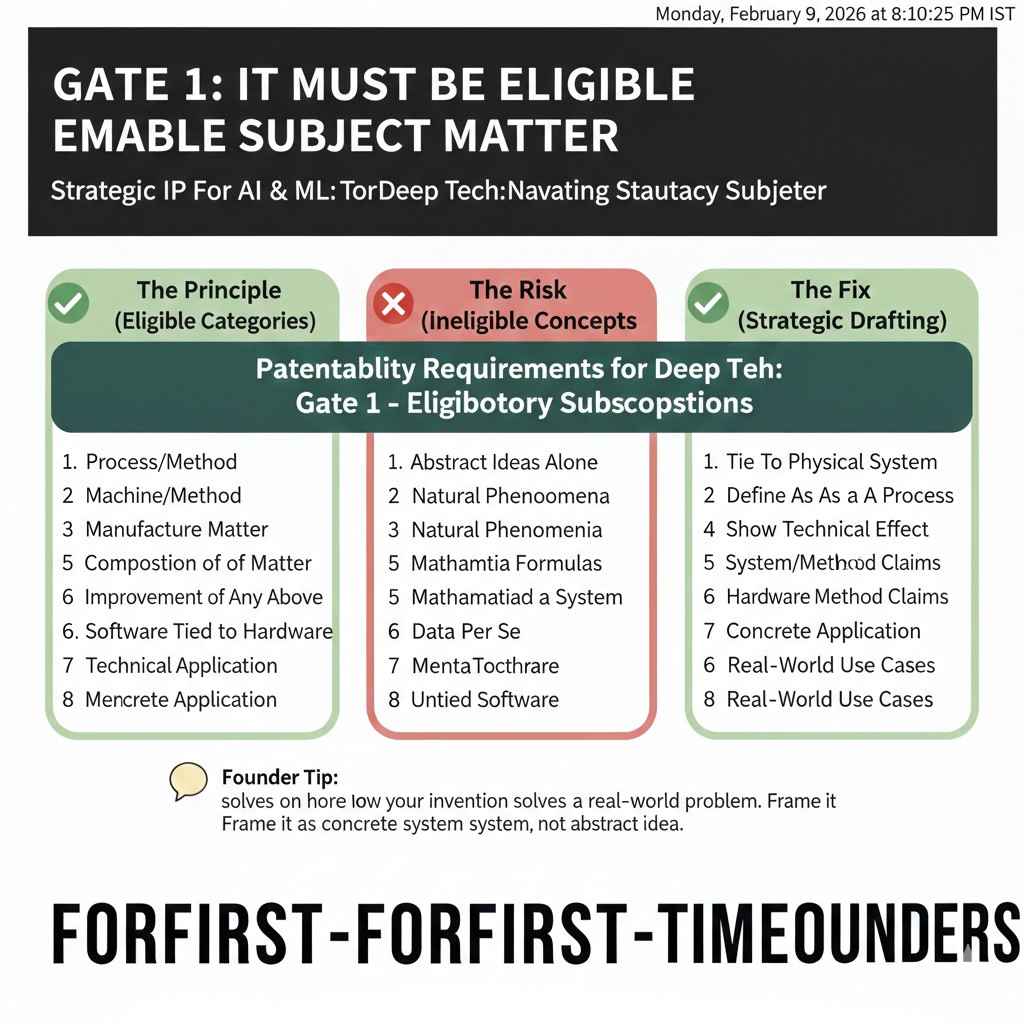

Gate 1: It must be eligible subject matter

This is the “Are patents allowed on this type of thing?” gate.

In deep tech, the risk is that your work gets framed as a pure idea, a math formula, or a business method. AI teams fall into this trap all the time.

Example of a weak framing:

“We use machine learning to predict equipment failure and reduce downtime.”

That sounds useful. But it can sound like “an idea” if you stop there.

A stronger framing sounds like a technical system:

“We use a sensor fusion pipeline that converts raw vibration data into a compressed feature stream, applies a specific model structure, then triggers a control action in a constrained time window, improving detection under noise and drift.”

Now you are talking about how it works, what data it takes in, what transforms happen, what the system outputs, and what technical issue is improved.

Deep tech inventions often are eligible. The problem is not the tech. The problem is how it is explained. If the story is too high-level, it looks like an abstract idea. If it is tied to a real pipeline, device behavior, or system limits, it becomes much easier to defend.

If you want Tran.vc to help you frame your invention the right way early—before you publish, demo, or ship—apply here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Gate 2: It must be new

This is called novelty. It means the exact invention you are claiming must not already be publicly disclosed anywhere in the world.

“Public” is broad. It includes:

- papers and preprints

- blog posts

- GitHub repos

- talks, slides, workshops

- product docs

- patents and published patent applications

- sometimes even videos or forum posts

If an examiner finds a single reference that shows every part of your claim, that claim is dead.

Here is the tricky part in AI and robotics: you might think your idea is new because nobody else has your product. But patents are not about products. They are about technical disclosures. A random academic paper from five years ago can kill your “new” claim even if nobody ever built it into a company.

That is why serious teams do prior art searching early. Not to get discouraged. To aim the patent at what is truly different.

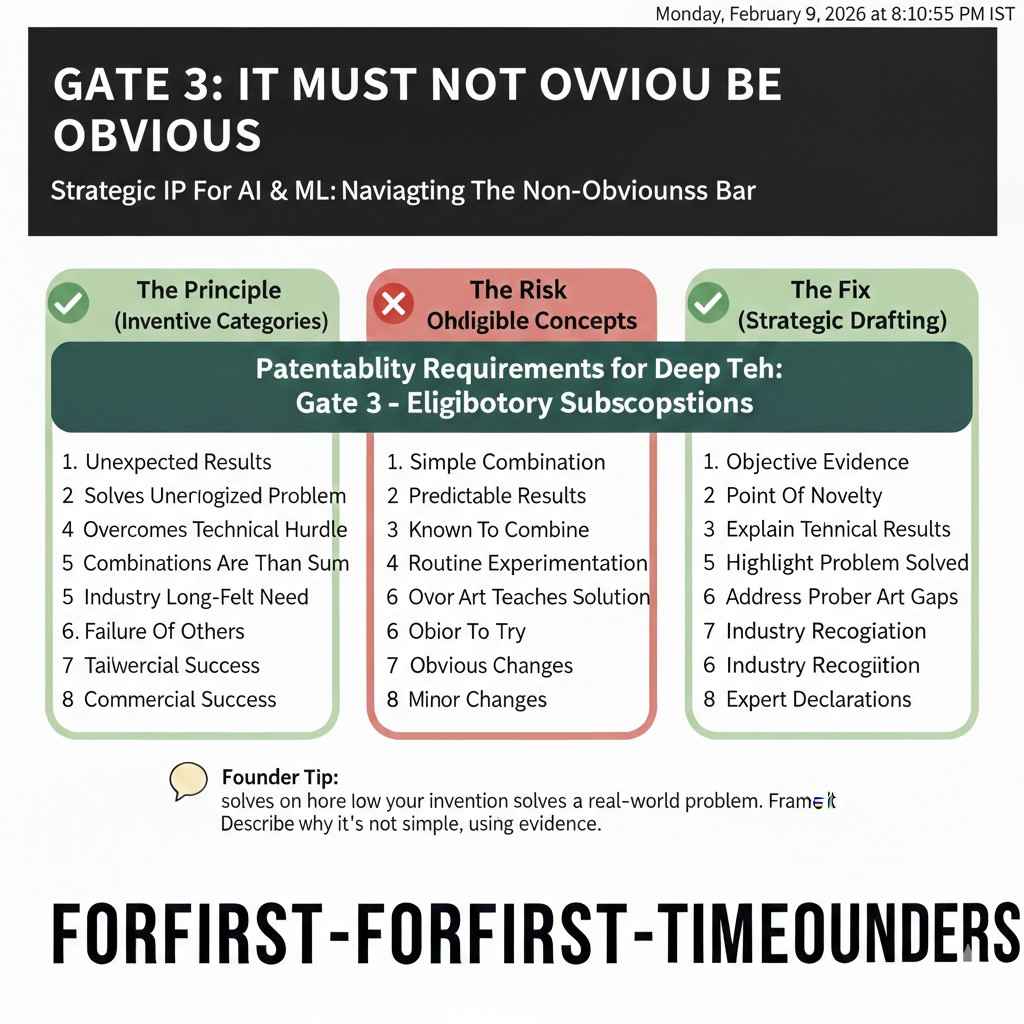

Gate 3: It must not be obvious

This is called non-obviousness. It is usually the hardest gate.

It means: even if no one showed your exact invention, would it have been an easy, expected step for a skilled person to combine known ideas to get your result?

In deep tech, obviousness attacks often look like this:

- “Paper A shows method X.”

- “Paper B shows method Y.”

- “It would have been obvious to combine X and Y to get what you claim.”

Founders hate this because they know combining X and Y was not “easy.” It took weeks of failure, tuning, edge cases, and clever hacks.

But patent law does not reward pain. It rewards a defensible difference.

So you have to give the examiner something solid. Something that makes your approach more than a simple mash-up.

In practice, what helps is specificity: a structure, a constraint, an ordering, a parameter choice, a control loop, a timing rule, a data representation, a training process with a real reason behind it, or a system interaction that is not standard.

Sometimes the best patentable part is not “we used model Z.” It is “we made model Z work under these constraints, with this pipeline, in this environment, and here is the trick that made it stable.”

That’s the kind of invention that can survive an obviousness challenge.

Gate 4: You must teach it clearly

This is disclosure. In the U.S. you will hear “enablement” and “written description.”

It means your application cannot be a vague story. It must show that you actually possess the invention, and that a skilled person could reproduce it without guessing.

This is where deep tech teams can win, because you often have real engineering detail.

But it is also where teams can lose, because they try to “hide the sauce.” They want a patent, but they don’t want to reveal too much. So they write around the real method. That can backfire.

A good patent does not require you to give away everything. But it does require you to describe enough that the invention is real, repeatable, and not just a concept.

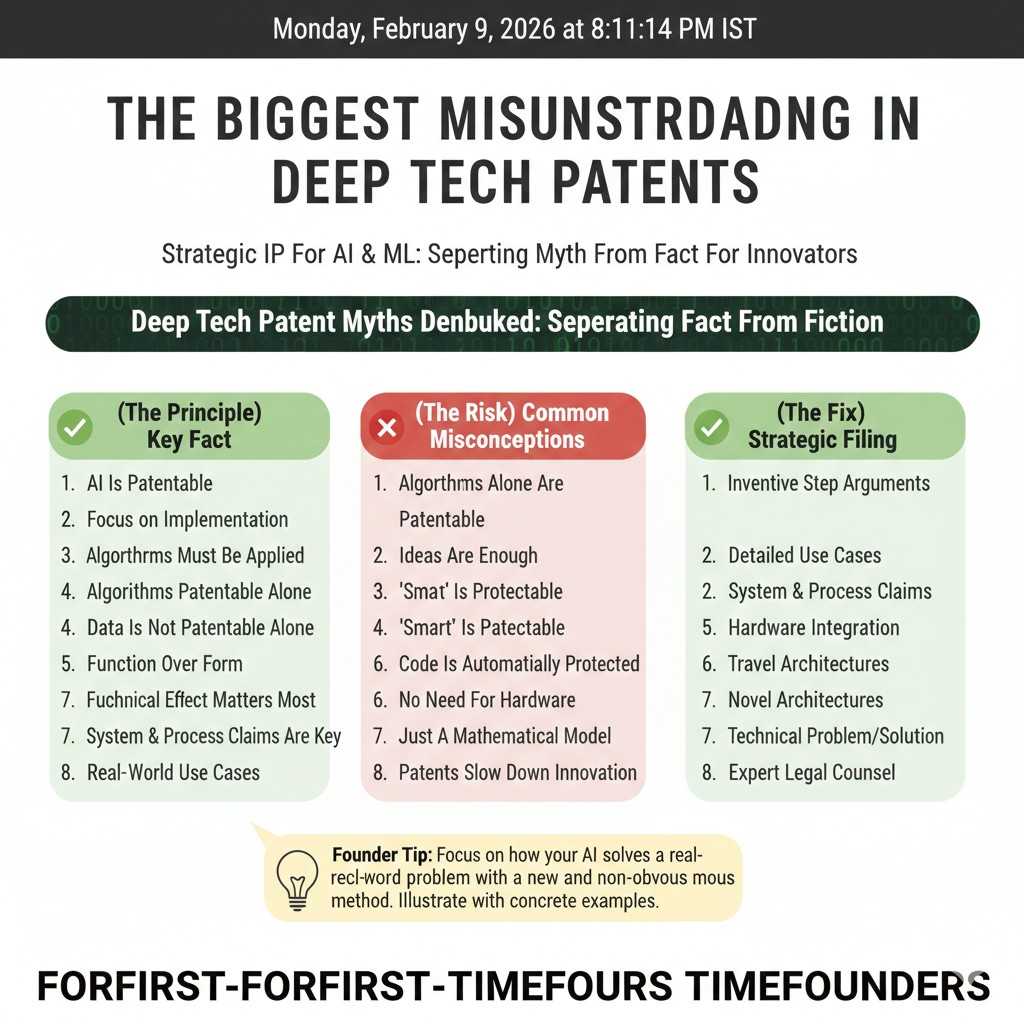

The biggest misunderstanding in deep tech patents

A lot of founders think:

“My invention is my model.”

Often, your model is not the invention. Or at least, it is not the strongest claim.

Models change. Architectures age fast. “We use a transformer” is not going to impress an examiner, and it may not hold up for long.

What tends to be patentable is the full system behavior: how data is captured, how it is cleaned, how it is turned into signals, how it is used in a loop, how edge cases are handled, how safety is enforced, how compute limits are met, how drift is detected, how the robot recovers when sensors lie, how training and deployment are tied together.

Deep tech patents are often about systems, not just algorithms.

Even when the invention is algorithmic, the patent usually becomes stronger when the algorithm is described as part of a technical process that changes real-world behavior: faster processing, lower error under noise, stable control, reduced memory, improved battery life, safer motion planning, fewer false alarms, better calibration, stronger privacy, or better latency.

If you can’t point to the technical pain your invention solves, you are going to struggle. Not because you are wrong, but because the examiner will not see why it matters.

A practical way to test if your invention is “patent-shaped”

Here is a simple test you can run on your own invention.

Try to explain it in one sentence using this structure:

“We solve [specific technical problem] by [specific technical mechanism], which improves [measurable technical outcome] under [real constraint or environment].”

If your sentence sounds like a business pitch, it is not ready.

“We help factories reduce downtime using AI.”

That is a business pitch.

A patent-shaped sentence sounds like engineering:

“We detect early bearing wear in high-noise motors by converting multi-axis vibration signals into a time-aligned spectral map, applying a drift-aware classifier with an adaptive threshold, and triggering maintenance flags before failure, reducing false positives under temperature shift.”

That sentence is not perfect, but it is patent-shaped. It shows inputs, transforms, constraints, and outcomes.

If you can get to a patent-shaped sentence, you are halfway to a good filing.

Tran.vc helps founders do this kind of framing as part of the IP work they invest in. Apply here if you want that support: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

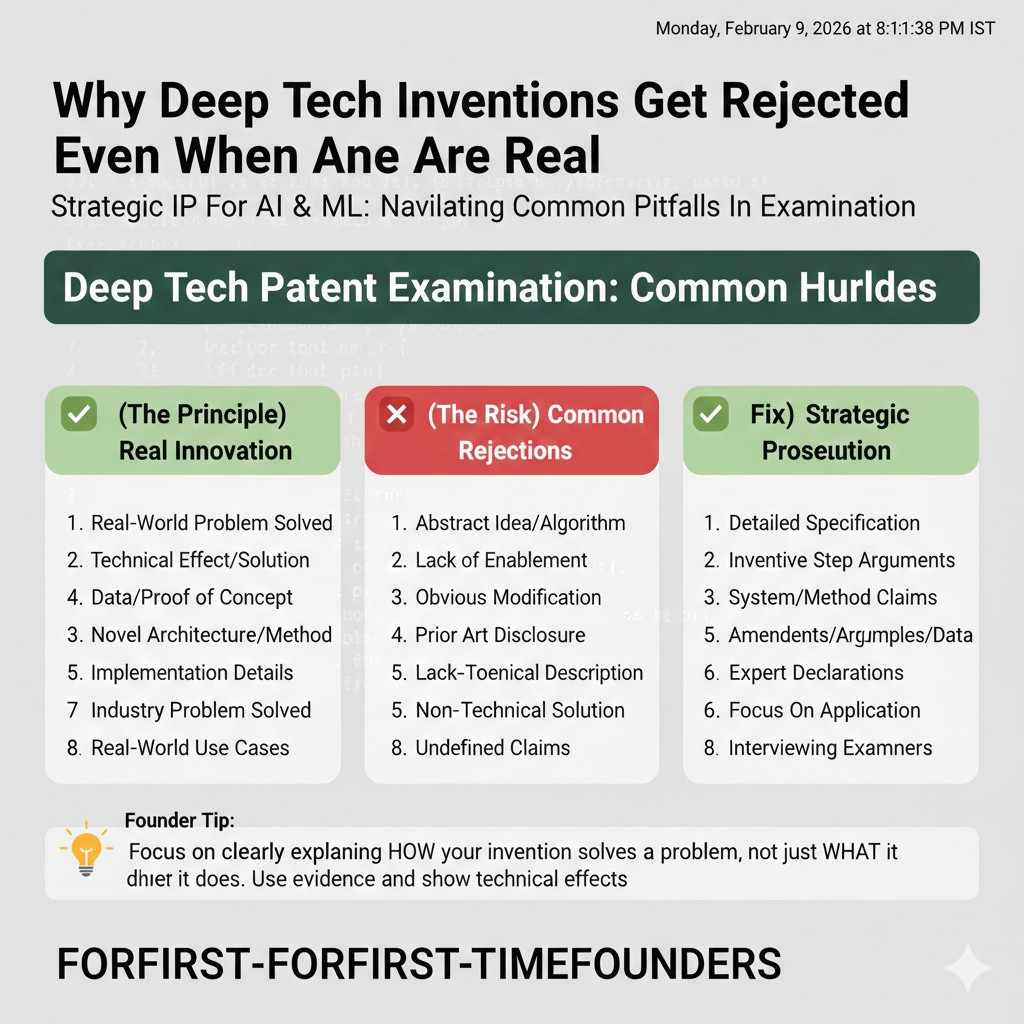

Why deep tech inventions get rejected even when they are real

Let’s talk about why rejections happen, in plain terms.

Most rejections are not personal. The examiner is not saying your work is useless. They are saying either:

- “Someone already showed this,” or

- “This is too close to what people already showed,” or

- “This is too vague or too abstract.”

Deep tech teams trigger #3 a lot, especially AI teams.

Why? Because AI language is often general:

- “We train a model.”

- “We use features.”

- “We predict outcomes.”

- “We optimize performance.”

Those phrases hide the real invention.

A strong patent application uses AI language only when needed, and leans on concrete detail: data structures, specific transforms, gating rules, error handling, sensor timing, model update rules, inference budgets, memory constraints, quantization choices, hardware interaction, feedback control, and deployment steps.

You do not need to write it like a textbook. But you do need to make it feel like a real machine someone could build.

A quick note on timing (because founders get burned here)

If you publish first, you may lose rights in many countries. In the U.S., you may have a limited grace period, but relying on that is risky if you want global protection.

Also, “publishing” is not just a paper. A public demo can count. A detailed blog post can count. A GitHub repo can count. Even a slide deck shared widely can count.

A very common founder mistake is waiting until after a launch or conference talk to think about patents.

If you are building something you think is defensible, you want to file before you go loud.

This is one reason Tran.vc exists: to help technical founders lock in IP early without spending years or giving up control. If that is relevant, you can apply anytime: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Patentable Does Not Mean “Smart” or “New to You”

What “patentable” really means in real life

A patent is not a prize for hard work. It is a legal right you earn by explaining your invention clearly, and showing why it is different from what already exists in public. That “public” part is what shocks many founders, because it includes papers, repos, talks, videos, product docs, and even older patents.

When people say “this is patentable,” they usually mean your invention can pass a set of strict tests. These tests do not care if your demo looks impressive. They care if your invention is new, not obvious, and explained in a way that a skilled person could build without guessing.

Why deep tech teams get this wrong at first

Deep tech founders often think the invention is the model, the robot, or the headline feature. But patents are about the exact way you solve a technical problem. If you describe your work like a product pitch, you often lose the case before it starts.

A strong patent story sounds like engineering, not marketing. It shows what goes in, what happens inside the system, what comes out, and why that path is not standard. If you can explain that chain with clean detail, you are already ahead.

A simple way to know if your idea is “patent-shaped”

Try to say your invention in one sentence that includes a real technical problem and a real mechanism. Not “we use AI,” but how your data is handled, what the model does differently, and what system limit it overcomes.

If your sentence could fit on a landing page, it is usually too broad. If it could fit inside a design review, you are getting closer. This shift in framing is often the difference between a weak filing and a strong one.

If you want help shaping this framing early, Tran.vc invests up to $50,000 in in-kind IP and patent work for AI, robotics, and deep tech startups. Apply anytime here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

The Four Gates Your Invention Must Pass

Gate one: is this the kind of thing patents allow

For software-heavy inventions, the first fight is often about whether the invention is “too abstract.” This happens a lot with AI because the language can sound like math or business logic if it stays high-level.

You can reduce this risk by tying your invention to a concrete technical system. That means describing the real pipeline, the real signals, and the real behavior changes in the device or computing system. When your invention looks like a working machine or a working process, it becomes easier to defend.

Gate two: is it new compared to what is already public

Novelty is strict. If one public source shows the same thing you are claiming, that claim will usually fail. The key is that novelty is judged against what is already disclosed, not what is already sold.

For deep tech, the danger is hidden prior art. A small workshop paper, an obscure thesis, or a patent filing from a different industry can still count. That is why strong teams search early and shape claims around what is truly distinct.

Gate three: is it more than an obvious next step

Non-obviousness is where many inventions struggle. Even if nobody showed your exact system, an examiner can argue it would be obvious to combine known ideas to get the same result.

To fight this, you need to be specific about what makes your solution hard to reach. That usually means showing a technical constraint, a special ordering of steps, a non-standard representation, or a control rule that is not a simple swap-in from the literature. It helps even more when you can explain why common approaches fail in your setting, and why your approach avoids that failure.

Gate four: did you teach it clearly enough

A patent is not allowed to be a vague outline. You must describe the invention so that a skilled person could make it work, without needing secret knowledge.

Deep tech teams often fear “giving away the secret.” The better way to think about it is this: you do not have to publish every tuning detail, but you do have to describe the structure clearly. If you try to hide the core trick, you risk failing the disclosure test and ending up with a weak asset.

The Big Problem in Deep Tech: “It Sounds Abstract”

Why AI inventions are easy to misjudge

AI language is often general on purpose. People say “train the model,” “extract features,” “predict outcomes,” and move on. That is fine for a talk, but it is dangerous in a patent.

Patent examiners read thousands of applications. If your wording feels like a reusable template, it becomes easy to reject as an abstract idea or as too close to prior work. The goal is to show that your invention is a specific technical solution, not a general goal.

How to make an AI invention look concrete

You make it concrete by describing the parts that do not change when the model changes. That often includes how you collect signals, how you clean them, how you represent them, what decisions your system makes, and how those decisions affect the real world.

If your system runs on the edge, talk about compute limits, memory limits, latency limits, and battery limits. If your system runs in robotics, talk about sensor noise, delays, missed frames, control stability, and safe fallback behaviors. These are not “extra details.” In deep tech patents, these details are often the invention.

How robotics inventions get weakened by vague words

Robotics teams sometimes describe the robot as a black box. They say the robot “detects,” “plans,” and “moves,” but they do not show the technical mechanism that makes the robot reliable.

A stronger description explains the full loop: sensing, state estimation, planning, control, and how failures are handled. Many robotics inventions are patentable because they handle real-world mess in a new way. If you leave that mess out of the description, the invention can look generic.

Where the “Real Invention” Often Hides

It is often not the model, but the system

A lot of founders believe the model is the product, so the model must be the invention. But models shift quickly. Patent strength often comes from the method that makes the model useful in a hard setting.

That method can be in the data path, in the training flow, in the deployment pipeline, or in the feedback loop. In robotics, it can be the safety layer, the recovery behavior, or the scheduling logic that prevents a robot from acting on bad data.

The invention is often the fix for a painful constraint

Patentable work often starts as an ugly problem: sensors drift, data is missing, labels are weak, the robot slips, latency spikes, compute is limited, or the environment changes.

If you built a method that keeps performance stable under those pressures, you may have a patentable invention. Your job is to describe the pressure clearly, then explain the exact mechanism that resists it. That clear link is what helps the examiner see “this is not just a goal.”

Why “we improved accuracy” is not enough

Accuracy is a weak claim by itself because it sounds like an expected goal. Examiners often treat “better accuracy” as something anyone would try to get by tuning.

Instead, talk about what your method improves in a technical way. Maybe it reduces memory use while keeping error stable. Maybe it detects drift without full retraining. Maybe it improves control stability under noisy signals. These are more “technical” improvements, and they are easier to defend.

What Usually Kills a Deep Tech Patent Application

Being too broad at the start

Many founders want a wide moat, so they write broad language. The problem is that broad language attracts broad prior art. If your claim can cover ten different systems, an examiner can usually find at least one reference that matches it closely.

In practice, strong patent strategy often starts with a clear core that is narrow but defensible. After that, you can build outward with follow-on filings and a family of claims that cover variations. The first goal is to secure ground you can hold.

Being too close to what papers already say

Deep tech moves fast, and academic writing is detailed. If your invention matches a known technique with only a small change, the examiner may call it obvious.

This is why it helps to map your invention to what exists and ask: what is the part that is truly new? Sometimes it is a special data representation. Sometimes it is a training schedule tied to deployment behavior. Sometimes it is a timing rule that makes real-time control possible. Those “small” differences are often the most valuable ones, if they are well explained.

Writing like a brochure instead of a build guide

If your application reads like a sales page, it will feel empty to an examiner. A patent needs fuller technical paragraphs that show structure and cause-and-effect.

The strongest applications read like a careful engineering explanation, but still stay clear. They define terms, describe components, show flows, and provide examples. The goal is not to impress. The goal is to make the invention unmistakable.

Timing: When You File Matters More Than You Think

Public sharing can quietly destroy global rights

Many countries treat public disclosure as a hard stop. If you publish first, you may lose rights outside the U.S. Even in the U.S., relying on timing exceptions can be risky, especially if the public disclosure is messy or hard to date.

For founders, “public” can include investor decks that get forwarded, conference talks, demo days, public repos, medium posts, and detailed docs. It is easy to cross the line without noticing, because you are excited and moving fast.

A practical habit: file before you go loud

If you believe your work is defensible, the safest move is to file before major launches, big partnerships, or public demos. You can still talk about your product after you file. The filing creates a time marker and reduces fear around sharing.

This is one reason Tran.vc exists. Instead of telling founders to “spend $30k on patents,” Tran.vc invests up to $50,000 in in-kind IP and patent services so you can protect what matters early. Apply here anytime: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

A Quick Preview of What Comes Next

How to find the patentable core in your work

In the next section, I will show a practical way to pull the “core invention” out of a messy system. This matters because real products are complex, and patent claims need focus. We will use deep tech examples like robotics stacks and AI pipelines so the method feels natural.

How examiners search and how to think like them

We will also walk through how examiners look for prior art, and how to write in a way that anticipates the most common rejection paths. When you understand the examiner’s job, you can make your application easier to approve without weakening your protection.

How to describe AI and robotics inventions so they survive scrutiny

Finally, we will go deeper on how to write your invention as a technical improvement, not just an algorithm. This is the skill that separates “we filed a patent” from “we built a real moat.”