Most founders treat patents like a legal chore they’ll “do later.” That’s a mistake—especially if you plan to sell in the US, Europe, and China. In these three regions, the order you file, what you say, what you don’t say, and how you describe your invention can decide whether you get real protection… or a paper certificate that doesn’t stop anyone.

At Tran.vc, we help technical teams turn early work into strong IP—without forcing you to raise too soon. If you’re building in AI, robotics, or deep tech and you want a clear path, you can apply anytime here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Let’s be honest: you do not need “a patent.” You need leverage.

Leverage means this: when a big company copies you, you can push back. When an investor asks, “What stops others from doing this?” you can answer in one calm sentence. When a partner tries to squeeze you, you can hold your ground.

But filing in the US + Europe + China is not the same as filing in one place three times.

Each region has its own rules, habits, and traps. The same words that help you in the US can hurt you in Europe. The same disclosure that feels “safe” in Europe can create problems in China if you did not plan the timing. And if you do AI, the way you frame your work matters a lot more than most founders think.

So this article is not going to be fluffy. It’s going to be practical. I’ll show you how founders build a filing plan that fits real startup life: tight time, fast product change, small team, big goals.

Here’s the core idea you should keep in your head the whole time:

A global patent plan is not a form. It is a sequence.

Sequence is everything:

- What you file first

- What you hold back

- What you test before you lock words in

- When you turn a rough draft into a real application

- When you go wide (more countries) and when you stay narrow (one strong case)

And yes, you can do this in a way that does not drain your cash or slow your shipping.

If you want help making this real for your exact product, apply here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

(That’s the fastest way to get a clear IP plan without guessing.)

What “good” looks like across US, Europe, and China

A good international filing plan does three things at once:

First, it protects the right thing. Not the buzzword. Not the demo. The thing that creates your edge.

For robotics, that might be how you fuse sensors to hold stable grasp in bad lighting. For AI, it might be the way your system adapts using a small set of labels, or the way you keep output safe in the loop. For a chip + model stack, it might be the way your compiler changes compute order to cut power without losing accuracy. The point is: your moat is usually in the “how,” not the “what.”

Second, it matches how patents get enforced in real life.

If your invention can be seen inside a device, that’s one enforcement story. If it happens on a server, that’s another. If it’s a model update step that nobody can see, you need claims written so you can still prove use. This is one of the biggest gaps in founder-made filings: they protect something real, but in a way that’s hard to prove.

Third, it fits startup timing.

You can’t freeze your product for six months while you “finish IP.” You also can’t publish a blog post that kills your rights in Europe or China. Your plan must work with sprints, pilots, and launches.

That’s why the right strategy is not “file everywhere now.” That’s expensive and often dumb. The right strategy is usually:

- lock a priority date early,

- buy time to learn,

- then expand with better info.

But the details matter. A lot.

Apply anytime if you want Tran.vc to map this to your roadmap: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

The big rule: one story, three legal cultures

Think of the US, Europe, and China as three different audiences.

In the US, examiners are often more flexible on how you “argue” around prior art. The US also has a system (continuations) that gives you ways to keep working your claim scope later, if your first filing is done well.

In Europe, the system is stricter about how the application is written and what is supported. Europe also has more rigid rules around added matter. This is a fancy way of saying: you do not get to “add” new technical detail later. If it’s not in the original text, you may be stuck.

In China, speed and form matter. Translation quality matters. And local practice can shape outcomes more than founders expect. If your wording is loose, your protection can become thin.

Now here’s the key: You can write one core application that works in all three, but only if you plan it that way.

Most teams don’t. They write a US-style draft, then “convert” it for Europe and China later. That often leads to:

- claims that Europe treats as too abstract,

- weak support for key features,

- language that becomes risky after translation,

- and missed chances to claim the parts that matter in enforcement.

So the goal is not three separate patents. The goal is one strong source document that can travel well.

Start with a map of what you’re truly protecting

This is where founders usually rush. Don’t.

Before you file, you want to be clear about four things. I’ll keep this simple and practical.

1) What is the technical change you created?

Not the product. Not the outcome. The change.

Example:

- “We detect defects in parts” is not a technical change.

- “We detect defects by combining vibration signals with thermal drift correction using a time-synced fusion step that updates per batch” is closer.

2) Where does the edge live?

Is it in data collection, model training, inference, control loop, hardware layout, edge deployment, or the way humans interact with the system?

If you don’t know this, you will file too broad in the wrong way and end up with claims that look impressive but don’t protect your edge.

3) What would a copycat do?

This is the most useful question you can ask before writing a single patent sentence.

If a copycat can get 80% of your benefit by changing one small part, you must claim around that. You must cover variations.

Founders often claim their exact method, but not the family of nearby methods that a competitor would use to avoid infringement.

4) What can you prove they are doing?

Patents are not just about “is it new.” They’re about: can you show someone is using it?

If your secret sauce is hidden in a cloud model, you may need claims that cover:

- client-side steps,

- system-level behavior that can be measured,

- logs or outputs,

- or integration steps a customer can see.

This “proof” issue is why so many AI patents feel useless later. They read like a paper, not like an enforcement tool.

If you want Tran.vc to help you do this mapping fast, apply here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

A simple global filing sequence that works for most startups

Let’s talk sequence.

Many early teams do not need to file in all three regions on day one. What they need is a path that protects them now and keeps options open.

A common approach looks like this:

You file first in a way that gives you a strong earliest date. Then you use the next months to learn what to double down on. Then you expand internationally using a structured step.

This is where the “priority year” matters. Under the Paris Convention, once you file in one country, you generally have 12 months to file in other countries and claim that first date.

In plain words: file once, then you have up to one year to go wider while keeping the first date.

That one year is your planning window. Use it.

Provisional vs non-provisional: the honest truth

A US provisional can be a good tool, but only if it is done well.

A “thin” provisional that reads like a pitch deck does not really protect you. It gives you a date, but if it does not support the later claims, you may not get that date when it matters.

A good provisional is basically a real application in plain clothing. It needs:

- detailed description,

- clear alternatives,

- multiple versions of the method,

- and enough examples that you can later claim what you actually ship.

Some founders skip the provisional and file a full non-provisional first. That can be smart if you already have stable tech and you want a cleaner base for Europe and China later.

So the right answer is not “always provisional.” The right answer is: use a provisional when you need speed, but write it like you mean it.

Europe is where sloppy writing gets punished

Let’s focus on Europe for a moment, because Europe is the region where founders get surprised.

Europe cares deeply about what you originally wrote

In Europe, “added matter” is a big deal. If you later try to narrow or adjust claims using a detail that was not clearly disclosed, you can lose that claim.

This means your first application must include enough technical detail to support multiple claim paths later.

In practice, this means:

- describe multiple system setups,

- describe multiple data flows,

- describe multiple model types,

- describe different sensor sets,

- describe fallback options,

- describe what happens when inputs are missing.

You do not need to list everything. But you need to show that you understood the space and you built more than one path.

Europe dislikes “pure software” framing

For AI and software-heavy robotics, Europe often asks: where is the technical effect?

This does not mean you can’t patent AI in Europe. You can. It means you must explain it in a technical way.

Instead of “our model predicts X,” you often do better with:

- how the model affects a physical process,

- how it improves a computer itself (speed, memory, latency),

- how it improves signal processing,

- how it controls a machine in a real system,

- how it reduces errors in a measured way.

If your draft reads like a business case, Europe will push back. If it reads like a technical solution to a technical problem, you have a much better shot.

China: think translation, clarity, and fast moving timelines

China can be a strong region for patents—especially if your supply chain, manufacturing, or customer base touches China.

But your filing needs to be clean.

In China, wording needs to be crisp

Loose language can cause narrow claims. And the translation can either preserve your meaning or quietly distort it.

That’s why you want:

- consistent terms,

- clear definitions,

- less “poetic” language,

- and fewer phrases that rely on cultural context.

A simple example: if you use five different words for the same component across the draft, a translation can turn that into five “different” things. Then you get trouble later when you argue scope.

Timing matters if you plan to manufacture

If you plan to show prototypes, negotiate manufacturing, or share CAD files, you must plan your filing dates around that.

In many cases, founders do a global filing plan not because they fear copying by a big brand, but because they fear leakage in production. That is a real risk.

A strong China strategy can act like a fence around your manufacturing story.

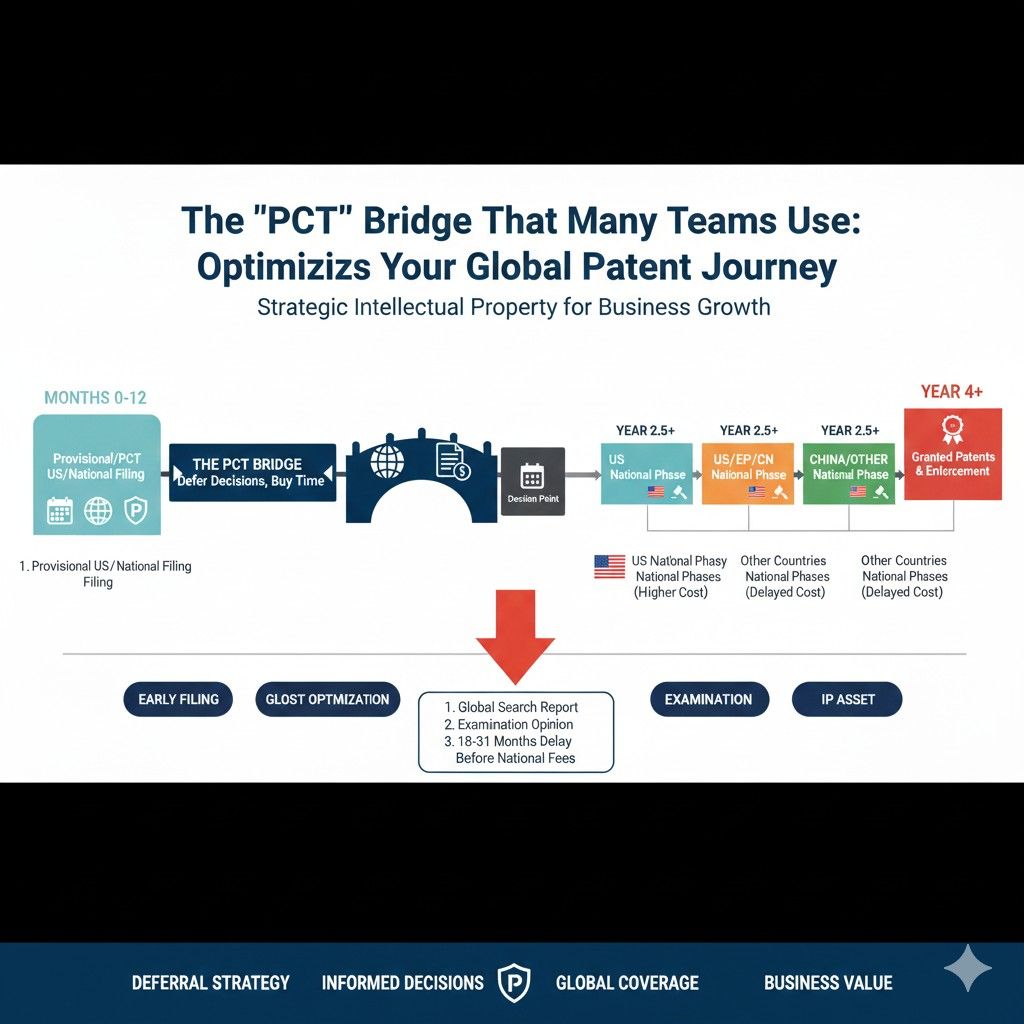

The “PCT” bridge that many teams use

Now let’s connect this.

A common and practical path for US + Europe + China is:

- File first (often US provisional or US non-provisional).

- Within 12 months, file a PCT application.

The PCT is not a “world patent.” It is a way to keep options open and delay some major costs while you learn more. Later, you “enter” each region (US, Europe, China) from the PCT.

This can be a strong fit for startups because:

- you buy time,

- you get a search report that gives clues about prior art,

- you can adjust your business plan before paying for every country.

But there is a catch: the PCT is only as good as the first application you used as its base. If the base is weak, the whole tree is weak.

This is why the first filing matters so much.

What to put in the first filing so it survives all three regions

Here’s a very practical way to think about drafting, especially for AI + robotics:

You want your application to include:

- the problem in technical terms,

- the limits of old methods,

- your system’s architecture,

- your method steps,

- variations,

- and examples that show it works.

But the magic is in the “variations.”

If you only describe one neat pipeline, a smart competitor will copy the idea but change one step. You want to describe families of options so your claims can cover those nearby versions.

For example, if you do sensor fusion, you might describe:

- fusion at raw-signal level,

- fusion at feature level,

- fusion at decision level.

If you do model training, you might describe:

- supervised,

- semi-supervised,

- self-supervised,

- weak labels,

- synthetic data,

- online learning.

If you do control, you might describe:

- PID baseline with learned correction,

- model predictive control with learned constraints,

- policy learning with safety guard rails.

Not as a giant list in the application, but as short, clear alternatives written as “in some examples…” with enough detail to be real.

And remember: Europe cares that these alternatives are truly supported. That means you need to explain them, not just name-drop them.

If you want, I can continue into the next section where we get very tactical on:

- a region-by-region filing playbook (US vs EPO vs CNIPA)

- how to handle public demos, papers, open-source, and customer pilots

- the best claim shapes for AI + robotics so you can actually enforce

- how to build a “patent ladder” over 12–24 months without wasting budget

- and common mistakes that quietly kill your rights

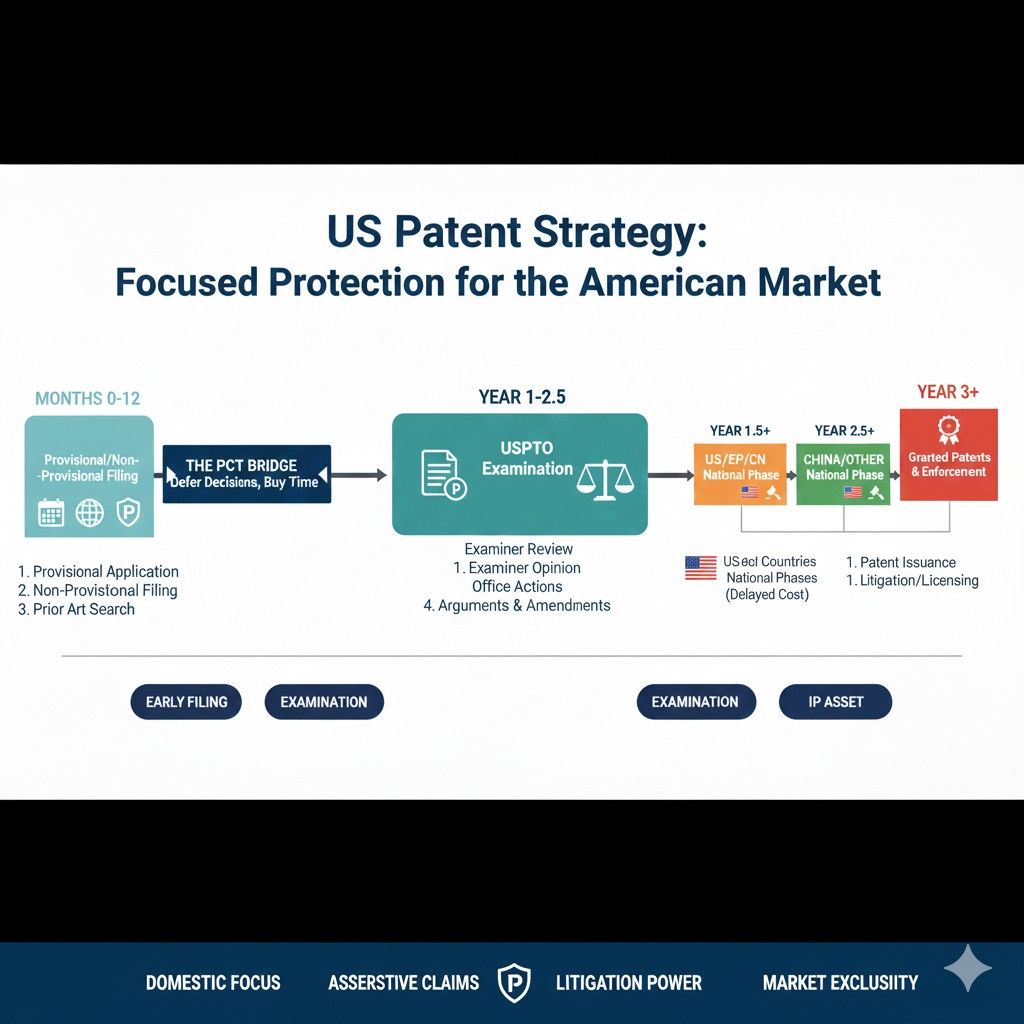

US Patent Strategy

Think in claim families, not one “perfect” claim

In the US, the best patent plans are built like a tree, not a single trunk. You start with a strong core idea, then you grow branches over time as the product and market become clearer. That matters because startups change fast. Your first filing should protect the engine under the hood, but also leave room to claim different versions later, including the version you will actually sell.

A common mistake is trying to nail the final product in the first draft. That locks you into words that may not match what you ship. A better approach is to describe the invention in layers: what is always true, what is often true, and what is optional. This gives you flexibility without losing the early priority date you need.

Use continuations as a business tool

The US system allows continuation filings, which can be a powerful lever when used with intent. In plain terms, you can keep an application family alive and file new claim sets later, as long as you have support in the original text. This helps when a competitor appears, when a buyer asks about coverage, or when you learn which feature customers value most.

This only works if the first filing is detailed enough. If the first document is thin, you cannot later “continue” your way into strong scope. So the tactical move is to draft the first application like a library of options. Then you can pick which chapters to claim as your market becomes real.

Provisional filings that actually protect you

A provisional is not a shortcut. It is either a real protective step or a false sense of safety. If your provisional is a set of slides and a few paragraphs, it may not support the claims you want later. When that happens, you can lose the benefit of your earliest date at the exact moment you need it.

A strong provisional reads like a real application. It explains the system, the method, the variations, and at least a few concrete examples. If you’re moving fast, you can file a strong provisional early, then add another provisional later for improvements. The goal is not to file once. The goal is to keep your story complete as your tech evolves.

AI and software in the US: avoid the “abstract idea” trap

In the US, software and AI patents can face eligibility issues if they look like a pure idea on a computer. You can reduce this risk by writing in a way that shows a real technical improvement. That improvement can be to a machine, to data handling, to speed, to memory use, to network load, or to a controlled process with measured outcomes.

The practical drafting tip is to focus on what changes in the system because your method exists. For example, if latency drops, if compute cost drops, if error rates improve under noisy inputs, or if safety improves in a control loop, say it clearly. Then tie your method steps to those results in a technical way, not a marketing way.

Robotics in the US: claim what’s measurable

Robotics inventions often combine hardware, software, and control. That is good news for US patents because it is easier to frame as a system that does real work in the real world. Still, you want claims that are enforceable. Enforceable means you can tell when someone is using your method, even if you cannot see their code.

You can improve enforceability by claiming inputs and outputs that a user can observe, and system behavior that leaves traces. If your robot calibrates itself in a unique way, or adapts grip force from a sensor fusion step, those behaviors can be tested and measured. You want your patent to cover the mechanism and the observable result, so proof is not impossible later.

Europe Patent Strategy

Europe rewards careful structure and punishes late changes

Europe is often the hardest region for founders who write patents like they write product specs. The European system is strict about what was originally disclosed. If you try to add detail later, or reshape the invention using language not clearly supported, you can lose claim scope. This is why the first application must be written with Europe in mind, even if you file in the US first.

The simplest way to act on this is to describe your invention with multiple supported variations from the start. You do not want one narrow pipeline. You want a set of supported options that can later become claims. When you do this well, Europe becomes less scary, because you are not trapped in one exact version of your method.

“Technical effect” is your north star

In Europe, a patent needs to solve a technical problem in a technical way. For AI, the danger is sounding like you are claiming a math method or a business rule. To avoid this, you frame the invention as a technical system change that produces a technical result. That result can be improved control stability, reduced noise sensitivity, better sensor alignment, lower compute load, better memory use, or higher safety in a machine loop.

This is not about adding fancy words. It is about explaining the cause-and-effect chain. If your model makes a robot safer, explain how the model output changes the control decisions, and how that reduces unsafe moves. If your method reduces server cost, explain how the method changes computation order, caching, or data flow to reduce resource use.

Drafting for Europe: support, support, support

European examiners often look closely at whether the claims are supported by the description. If your claim mentions a feature, the description should explain it in enough detail that it feels like part of the invention, not an afterthought. This matters even more when you later want to narrow claims to get around prior art. If the narrowing feature is not well described, it may not be allowed.

A practical habit is to include “fallback positions” in your original text. That means writing multiple versions of key steps with real detail. If your method can use different sensors, describe at least a few realistic sensor sets and how the method adapts. If your training can use different label types, describe how the pipeline handles each. You are building a reserve of supported options for later.

Europe and AI: make it feel like engineering, not theory

For AI inventions, Europe tends to respond well when the invention is tied to a specific technical context. Robotics, industrial inspection, medical imaging, network management, and battery systems are examples where AI can be presented as part of a technical process. You do not need to lock yourself into one vertical, but you do want your description to show real engineering constraints and real technical outcomes.

One useful approach is to describe the system boundary clearly. State what data comes in, what transformations happen, what constraints exist, and what the system outputs. Then show how your method improves the system under those constraints. This keeps the invention grounded and reduces the risk that it is treated as an abstract computation.

Avoiding hidden Europe killers: clarity and consistency

Europe can be unforgiving when terms are vague or inconsistent. If you call something a “node” in one place and a “module” in another, that can create confusion. If you describe the key step differently in different sections, it can weaken your story. Consistency is not just style. It is legal strength.

The tactical move is to define your key parts early, use the same words throughout, and avoid loose phrases like “any suitable method.” It is fine to describe alternatives, but each alternative should be written clearly, not hand-waved. This makes examination smoother and helps later if you need to defend the scope.

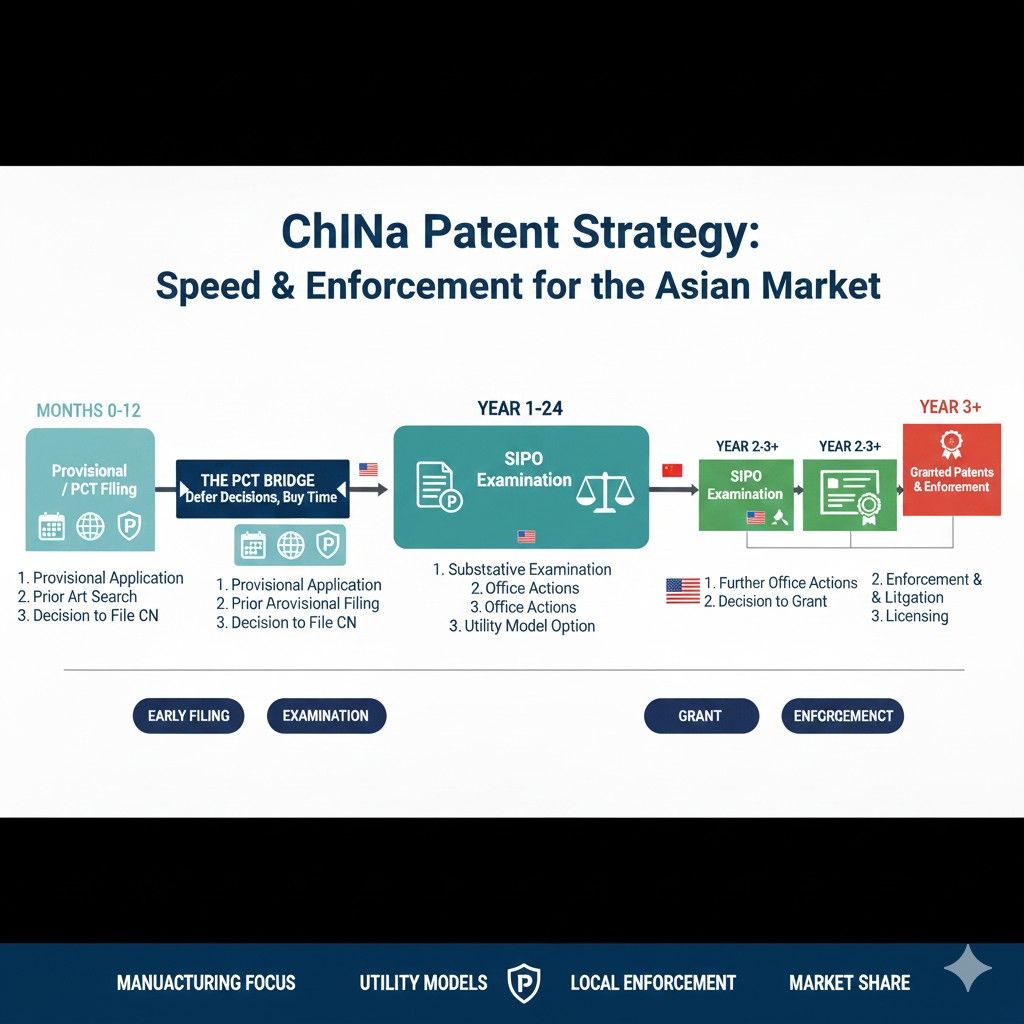

China Patent Strategy

China values crisp language and clean support

China is a major market and a major manufacturing hub, so protection there can be a real business shield. But China does not reward vague drafting. If your terms are loose, your claims can end up narrow. If the text is hard to translate, the meaning can drift. When meaning drifts, you may get a patent that does not match what you built.

This is why your base document should be written with translation in mind. You want short, clear definitions of key terms. You want consistent naming. You want fewer idioms and fewer “marketing” phrases. The goal is not to write like a robot. The goal is to write so your technical meaning survives the trip.