Robotics is expensive. Parts cost money. Testing takes time. Hiring is hard. And yet, the one thing that can raise your odds with customers and investors is often ignored until it’s too late: patents.

If you are building robots, you are building real “how” — not just a brand, not just a landing page. Your edge is in your motion planning, control loops, safety logic, sensing stack, grippers, calibration flow, fleet updates, data pipeline, and the way your system works end-to-end. Those are the pieces competitors will try to copy the moment you show traction.

Here is the good news: a smart patent plan does not require a huge budget. What it requires is clear thinking, good timing, and a simple process your team can follow even when you are moving fast.

Tran.vc helps robotics and AI founders do exactly this. We invest up to $50,000 in in-kind patenting and IP services so you can protect what matters early, without burning cash you need for building. If you want help turning your robotics work into a real moat, you can apply anytime here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

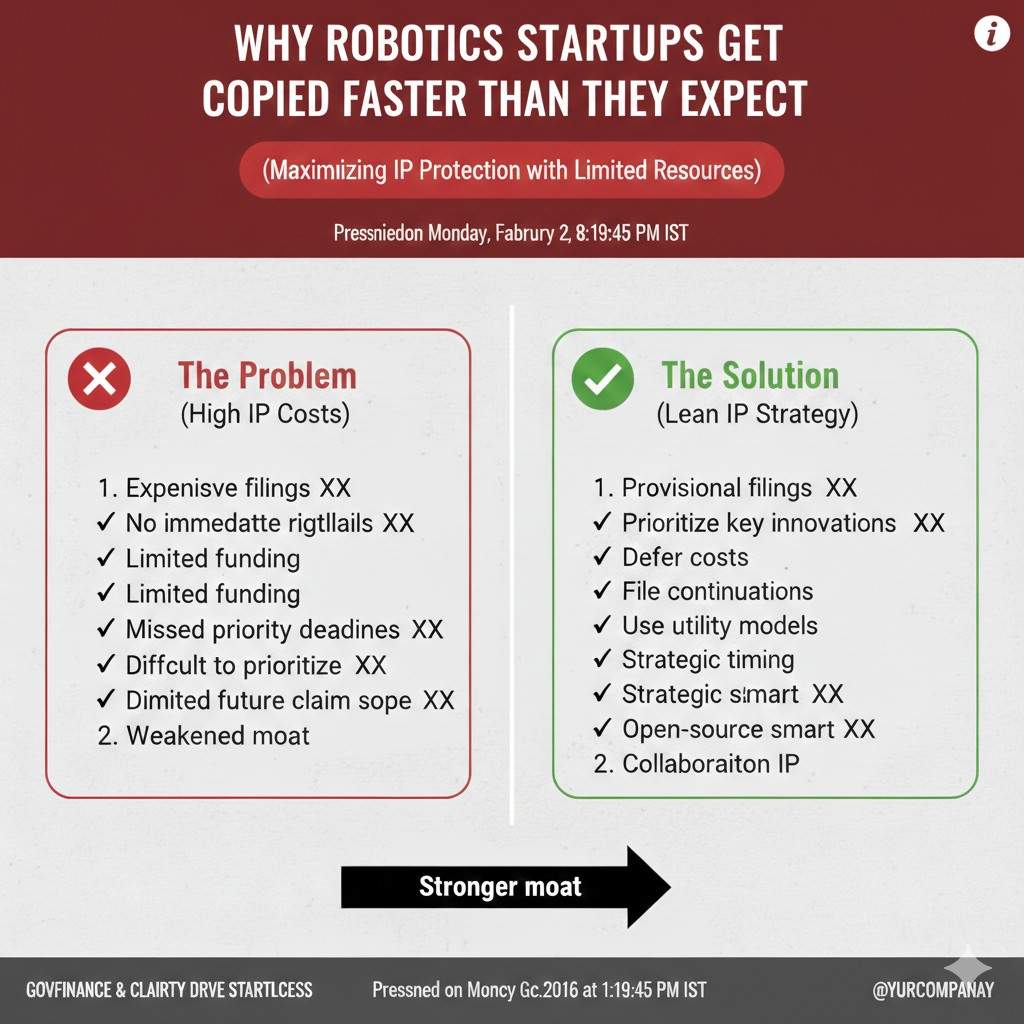

Why robotics startups get copied faster than they expect

Robotics looks “hard,” so many founders assume copying will be slow. But the truth is more annoying.

A competitor does not need to copy your full robot. They can copy one key method and gain most of the benefit. They can copy a calibration trick that cuts setup time in half. Or a safety routine that reduces damage. Or a controller that reduces wobble at high speed. Or a training loop that makes grasping work in messy bins. Those are small pieces that deliver big results.

And robotics companies share a lot in public without realizing it. Demos, videos, conference talks, hiring posts, GitHub snippets, customer pilots, even a support doc can reveal your approach.

Once that happens, you cannot undo it. In many places, public disclosure starts the clock. If you wait too long, you may lose the right to patent the thing you proudly showed on stage.

So the goal is not “patent everything.” The goal is “capture the right ideas early, in a low-cost way, before you accidentally give them away.”

That is the mindset that keeps you safe on a tight budget.

The budget myth: “Patents are only for big companies”

Patents can be costly if you do them in a messy way. They can also be reasonable if you plan them like a product roadmap.

Most startups waste money on patents in three ways:

First, they file too late, when they already showed the work to the world and now the patent has to dodge around what is already public.

Second, they file too broad, too early, without enough detail. Then the application gets rejected, and they pay again and again to fix it.

Third, they file the wrong things. They protect a feature that is easy to work around, and skip the method that actually creates the advantage.

A good plan avoids all three.

A good plan also uses the tools that exist for budget control. The biggest one is filing in stages. In the U.S., that often means starting with a provisional application so you can lock a date and keep building, then converting later when you have more proof and better claims.

You do not need a large “patent portfolio” to look serious. You need a small set of filings that protect the core of your robotics system.

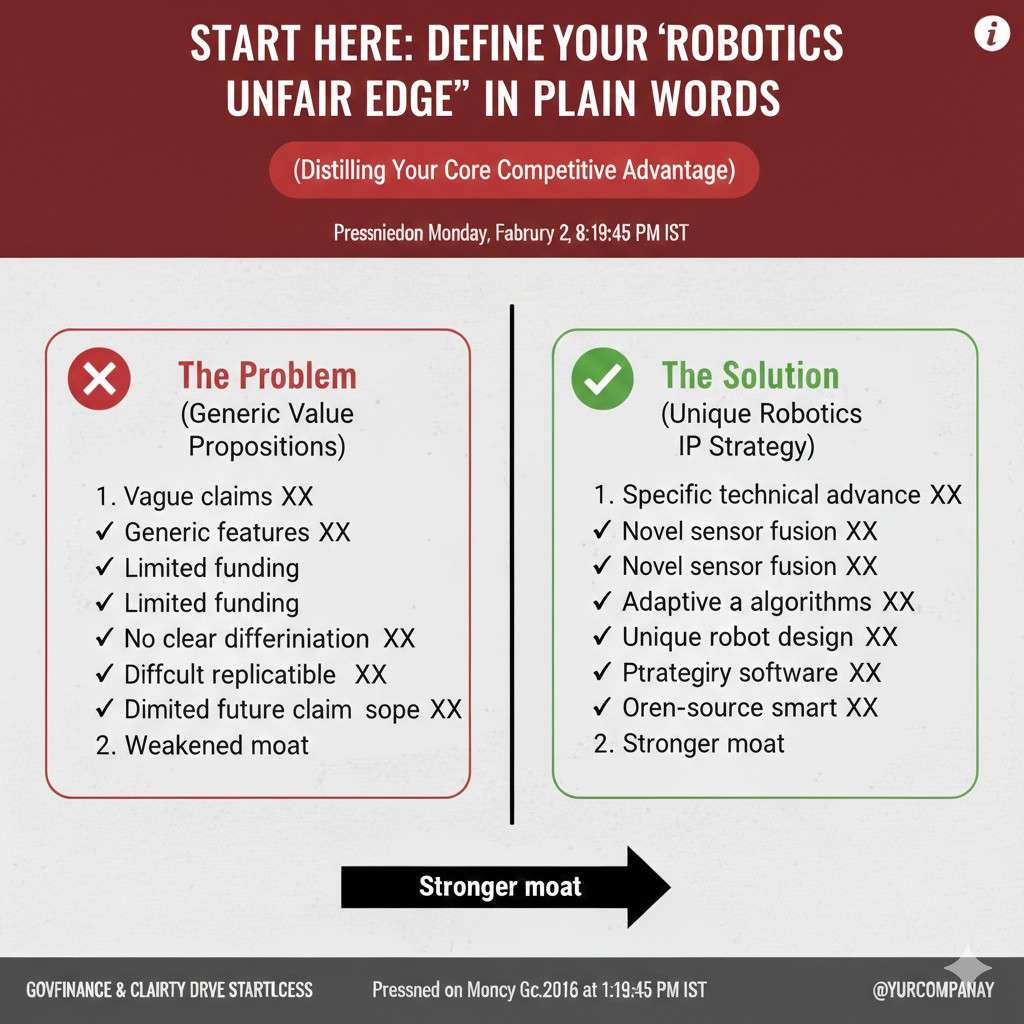

Start here: define your “robotics unfair edge” in plain words

Before you talk to any attorney, you should be able to explain your edge in a few short sentences a non-expert can understand.

Not marketing language. Just simple truth.

For example:

- “Our robot can pick soft items without crushing them because it changes grip force based on real-time slip.”

- “Our drone lands safely in wind because it uses a sensor fusion method that estimates gusts and adjusts thrust.”

- “Our warehouse robot routes itself around people using a prediction model that runs fast on cheap hardware.”

- “Our arm calibrates itself in five minutes using a camera and a simple motion routine, not a long manual setup.”

When you can say it simply, you can protect it better.

Now, take that simple statement and ask one hard question: what part is actually new?

In robotics, “new” often lives in the steps and logic, not in the parts. It’s usually not the camera itself. It’s what you do with the camera. It’s not the motor. It’s the control method. It’s not the model. It’s the training method, the labeling loop, the safety guardrails, the way you use data after deployment.

That is where patent value sits.

A tight-budget rule: don’t patent outcomes, patent methods

Many founders describe an invention as an outcome:

“Robot can grasp better.”

That will not help you. Outcomes are easy to claim and easy to reject.

Instead, describe the method:

“Robot estimates slip using micro-vibrations from a sensor in the gripper, then adjusts force using a two-stage controller with a threshold and a decay function.”

That is a method. It has steps. It has structure. It is harder to copy without touching your protected path.

Even if a competitor uses a different sensor, or a different threshold, your claims can often still cover the “spine” of the method if drafted well.

This is one reason robotics is a strong patent area when done correctly. The work tends to be procedural and system-based. That maps well to patent claims.

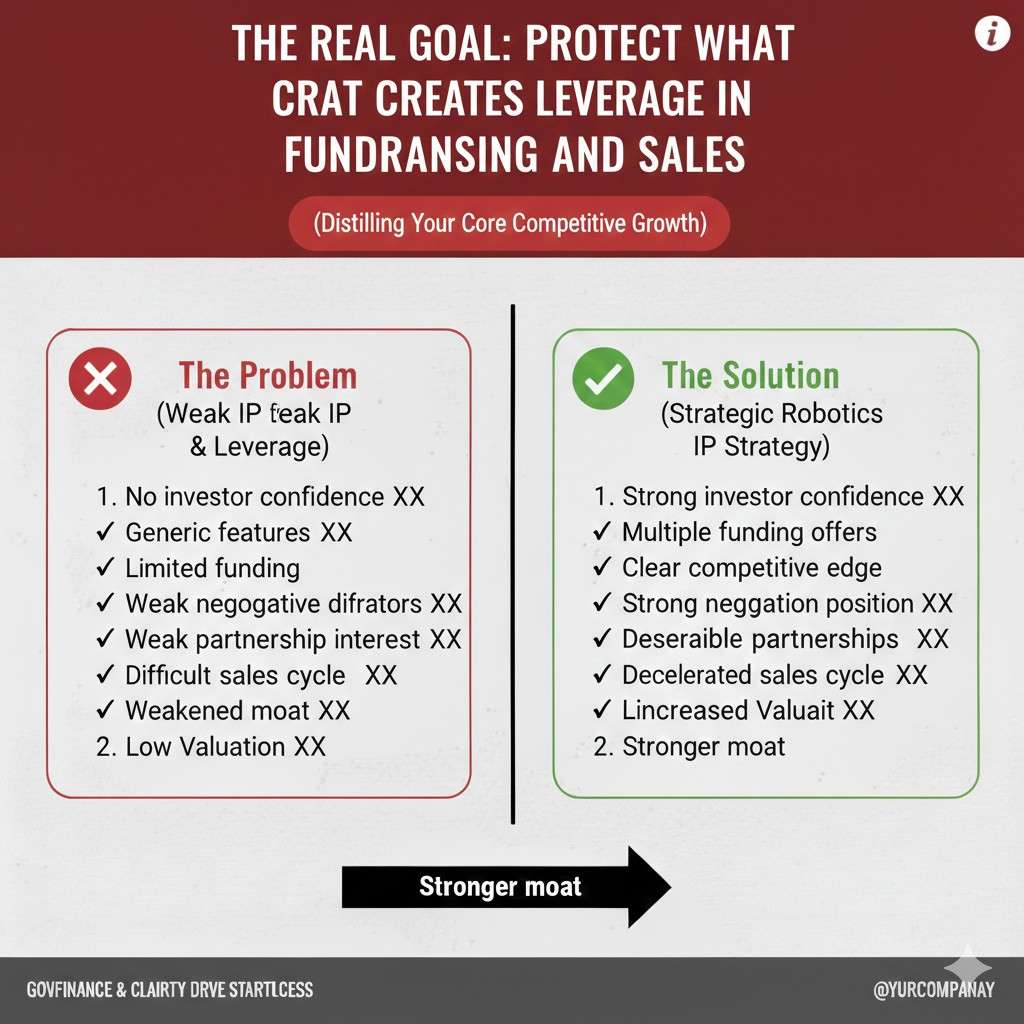

The real goal: protect what creates leverage in fundraising and sales

A patent strategy should serve business strategy. On a tight budget, every filing must earn its keep.

In robotics, patents help in three main moments:

1) When investors ask, “What stops a bigger team from doing this?”

If your only answer is “we execute faster,” the meeting often ends politely. Not because speed is bad, but because speed is not a moat. It is a race.

A well-picked filing lets you say: “We are protecting the key method that makes our performance possible.” That shows maturity. It also signals you will not be defenseless if the market turns hot.

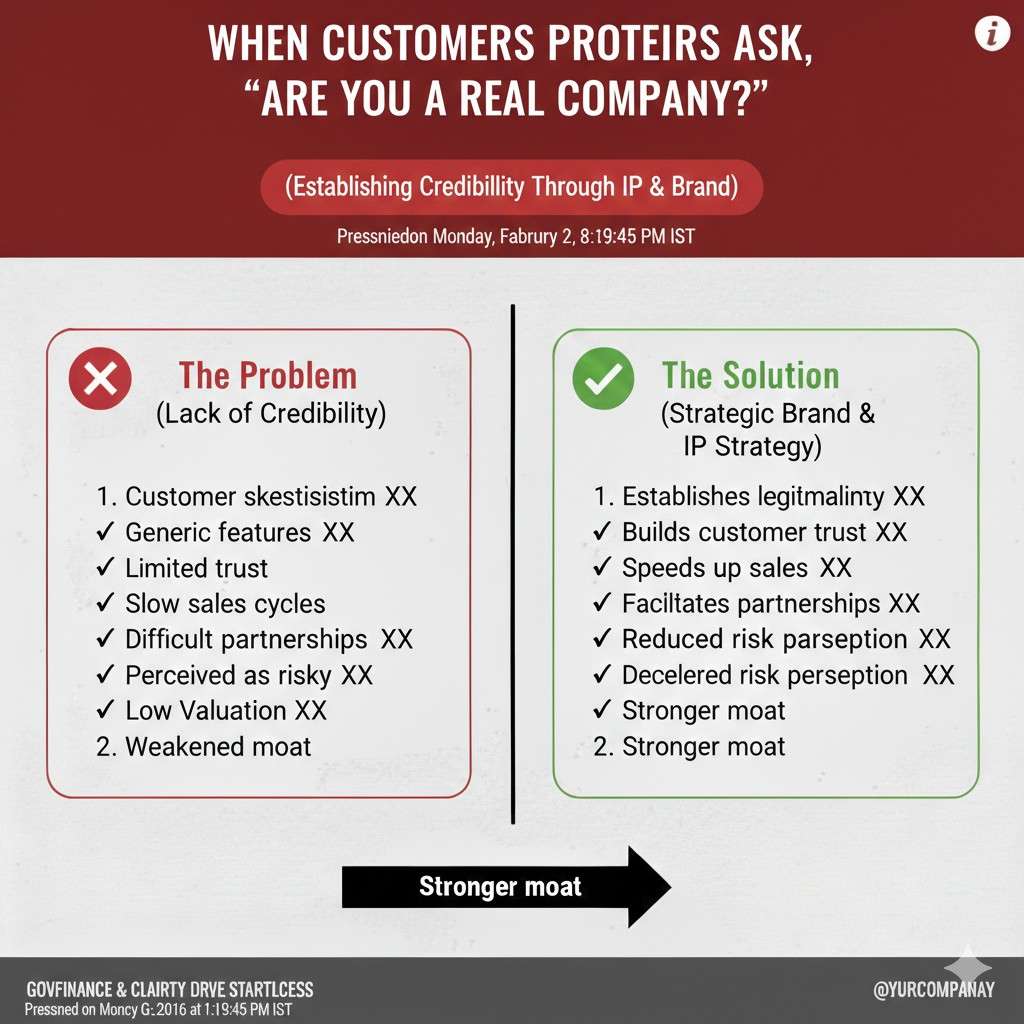

2) When customers ask, “Are you a real company?”

In robotics, customers worry about risk. They worry you will disappear. They worry support will be weak. They worry a supplier will sue you. They worry your tech is a science project.

Patents do not solve all of that, but they are a strong signal that you are building something real and defensible.

3) When competitors get too close

Sometimes a patent is not about lawsuits. It is about the quiet power of being able to say, through counsel, “We have filings in this area.” That can change behavior.

The best time to have that power is before you need it.

If you want a partner to help you pick the right filings for leverage, Tran.vc is built for that. We invest up to $50,000 in in-kind patent and IP work, so you can protect your core while you keep cash for building and shipping. Apply anytime here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

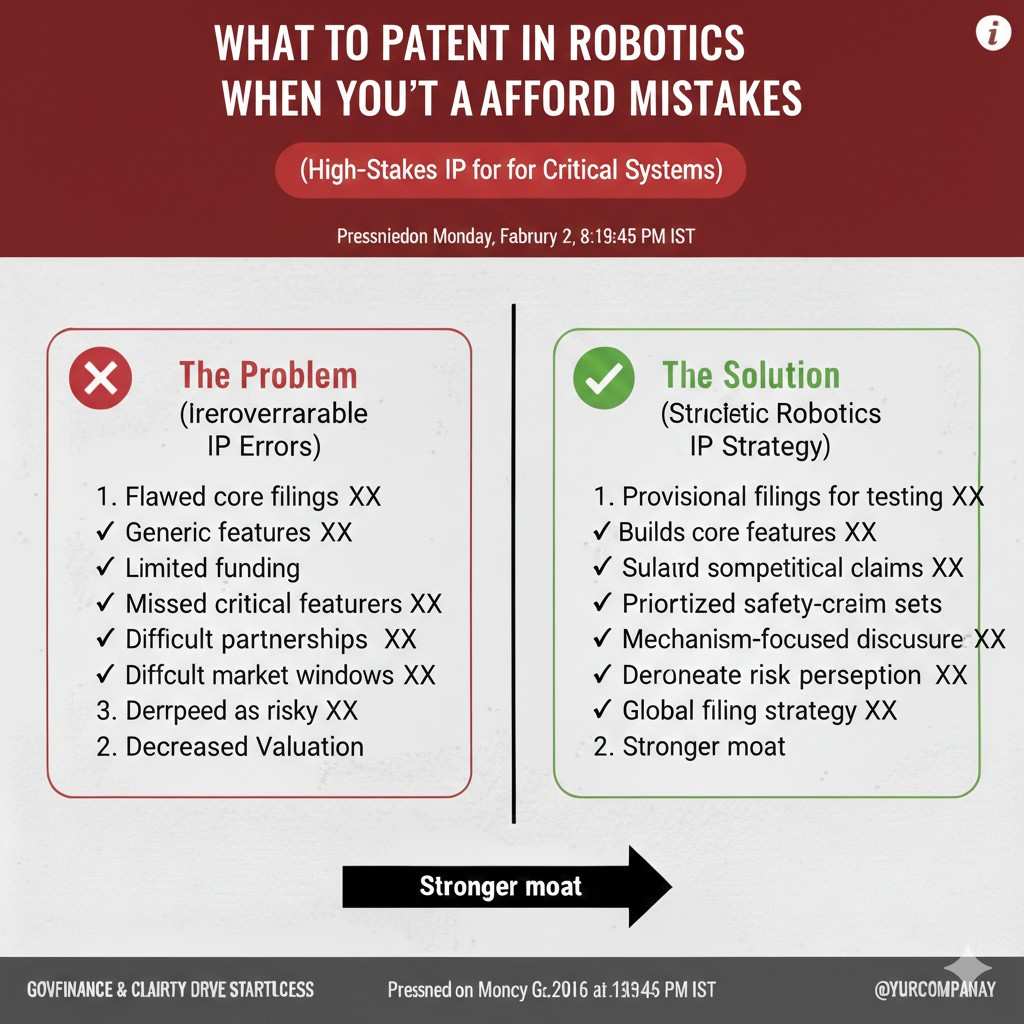

What to patent in robotics when you can’t afford mistakes

Let’s get very practical.

A robotics company usually has many “ideas.” But only a few are worth patenting early.

The best early targets tend to be:

The method that makes the robot work in the messy real world

Lab demos are easy. The real world is chaos. If you solved the chaos, that is valuable.

Examples include: handling edge cases, recovering from failure, safe fallback modes, and reducing the need for perfect conditions.

If your robot keeps working when lighting changes, when floors are uneven, when objects vary, when sensors drift, when humans do weird things — those are strong places to look.

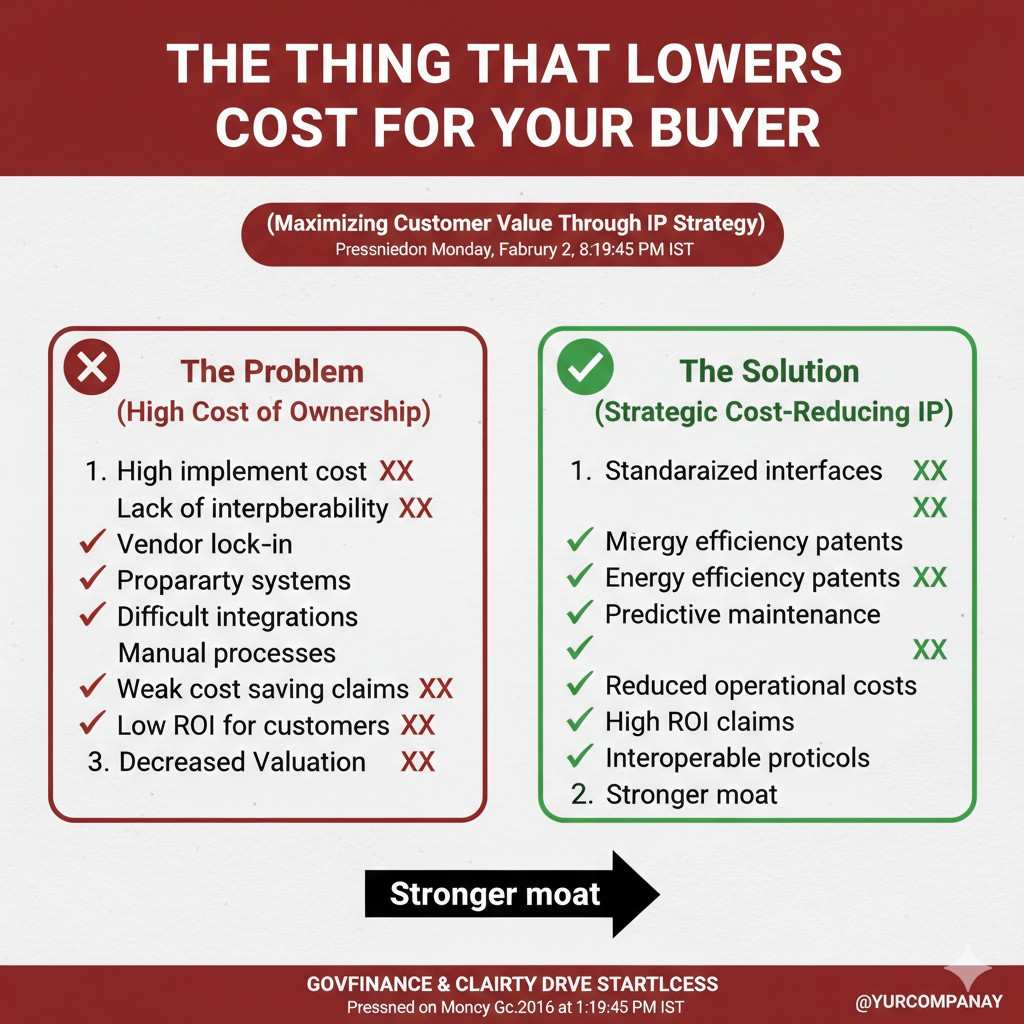

The thing that lowers cost for your buyer

Robots often lose deals because the buyer does not want to change their process. If your system reduces setup time, maintenance time, training time, or operator time, that is business value. That is also a patent target.

The system glue

In robotics, the “secret sauce” is often how modules talk to each other. Planning to control. Perception to grasp. Cloud to edge. Fleet to updates. Teleop to autonomy.

That glue is hard to see from the outside, which makes it tempting to ignore. But it is often exactly what competitors try to mimic once they learn your architecture.

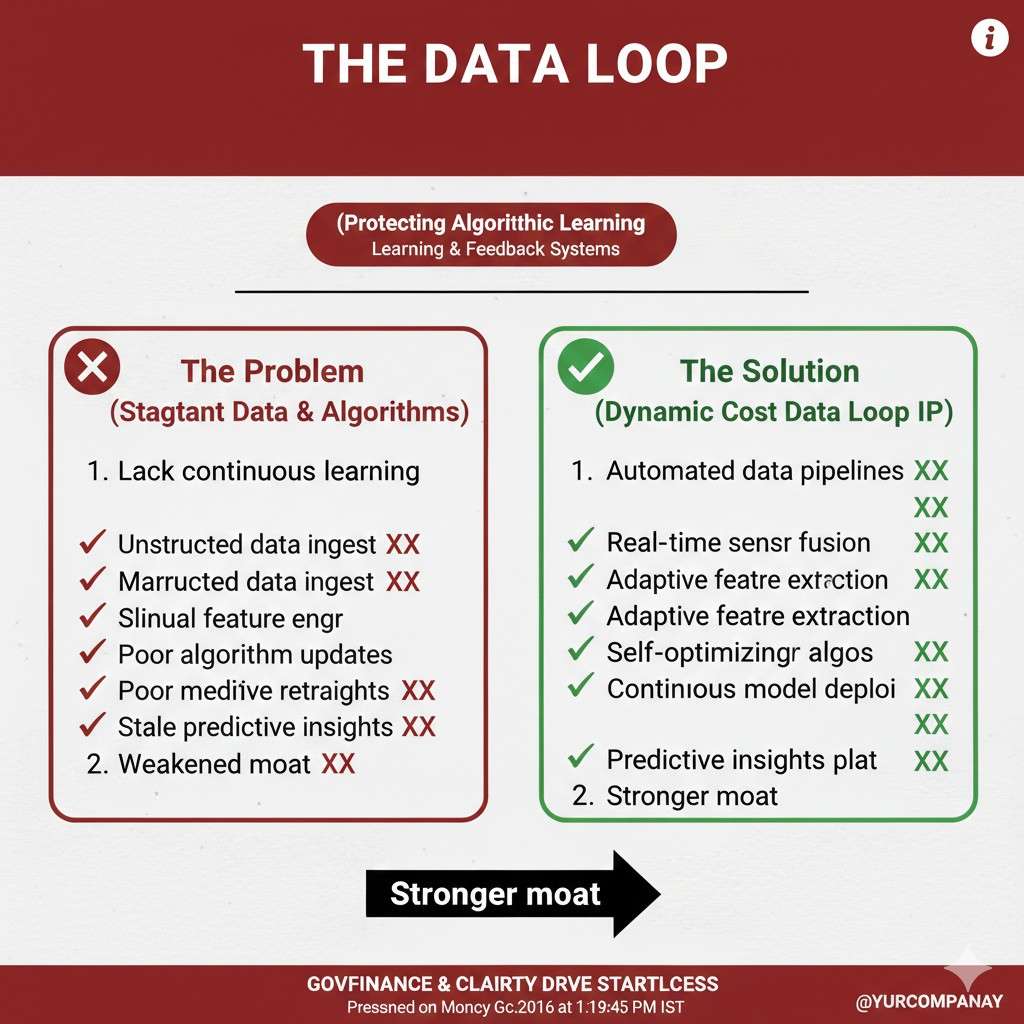

The data loop

If you use real-world runs to improve performance, you probably have a loop: data capture → labeling → training → validation → deploy → monitor → repeat.

If your loop is special, protect it. Even a small improvement in this loop can create compounding advantage.

A big mistake is thinking, “We use AI, so it’s not patentable.” In many cases, the model itself is not the point. The method around the model is. The way you prepare data, run inference, handle uncertainty, and enforce safety is where claims live.

When to file: use milestones, not feelings

Founders often file when they “feel ready.” That usually means “after we show the demo.” That is backwards.

A tight-budget filing plan uses milestones:

Milestone A: You have a working concept and can describe the method clearly.

This is often the right time for a provisional, because you can capture the core idea before your first big reveal.

Milestone B: You have test results and you know what parts are essential.

This is a great time to add a second filing or an updated provisional that includes proof, variations, and better detail.

Milestone C: You are about to raise, or sign a large deal, or go public with deeper technical detail.

This is when you should be ready to convert the best provisionals into a full application.

This staged approach helps you avoid the trap of paying for a “perfect” patent too early. You lock the date, then you improve the content as your product becomes clearer.

How to create strong invention “notes” without slowing your team

Here is a simple practice that works well in robotics teams:

Every time you solve a hard problem, write a one-page invention note within 48 hours.

Not a big document. One page.

It should answer:

What problem did we face in the real world?

What did we try that failed?

What did we build that worked?

What steps does it use?

What are 3 ways someone might copy it differently?

What results did we see?

That is it.

This does two things.

First, it creates a record while the details are still fresh. Robotics work is full of tiny decisions that matter. You forget them quickly.

Second, it makes it much cheaper for an attorney to draft. You are basically handing them the structure.

This is how you keep patent costs down without sacrificing quality.

A strong invention note is also helpful for onboarding, future debugging, and investor diligence. It is a business asset even before it becomes a patent.

The most common robotics patent mistake: filing too narrow

A robotics team often patents the “exact” design they built. Then a competitor changes one piece and walks around it.

The fix is to think in layers:

- What is the core method that must happen?

- What are different ways to sense the key signal?

- What are different ways to compute the decision?

- What are different ways to apply the action?

You do not need a long list in your blog doc. You just need to train your brain to ask “how else could someone do this?” and capture those variants early.

This is why robotics patents often need cross-discipline thinking. A competitor might replace a sensor with another. They might replace a learned model with a heuristic. They might move compute from cloud to edge. Your filing should anticipate the obvious swaps.

That is not “over-lawyering.” That is just being practical.

Keep your patent plan aligned with your product plan

If you are pre-seed, your product will change. That is normal.

Your patent plan should not freeze you. It should follow the truth of what you are building.

A simple way to do this is to tie patents to your roadmap:

When a new feature becomes “core” and starts to prove itself, it becomes a candidate.

When a feature is still experimental, you keep notes but you do not rush.

When a feature is about to be shown publicly, you decide quickly whether to file.

This avoids filing a patent on an idea you later drop. That is a direct way to burn money.

Where Tran.vc fits in

Most technical founders do not need “more advice.” They need a partner that can actually do the work with them, without draining their runway.

Tran.vc invests up to $50,000 in in-kind patenting and IP services so you can:

- pick the right inventions to protect,

- draft filings that match your real system,

- build a clear IP story for investors,

- and avoid common mistakes that create expensive rework later.

If you are building robotics, AI, or deep tech and you want to protect your edge early, you can apply anytime here: https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Patent Strategy for Robotics Startups on a Tight Budget

Why a “tight budget” patent plan is different

A robotics startup does not fail because it lacks ideas. It fails because it runs out of time and money while building something hard. That is why patent strategy must feel like part of product work, not a side project that drains the team.

A tight budget plan is not about filing fewer patents. It is about filing the right ones, at the right time, with the right detail. When you do this well, you spend less, you reduce rework, and you create a clear story for investors and buyers.

What patents really do for a robotics company

A patent is not only a legal paper. It is a business tool that can protect your method, reduce fear for buyers, and increase your value in a fundraise. It also helps you stay calm when a bigger company starts building something that looks like your product.

Most important, patents help you protect the “how,” not the hype. Robotics value lives in the steps, the timing, the safety logic, and the system glue. That is the stuff a good patent can cover when it is written the right way.

A simple promise: you can do this without burning runway

Founders often delay patents because they assume it will be expensive and slow. The truth is that cost goes up when you wait too long, rush at the end, or file weak work that needs fixes. A smart plan keeps costs controlled by spreading work out and capturing ideas while they are fresh.

Tran.vc helps founders do this early by investing up to $50,000 in in-kind patent and IP services. If you are building robotics or AI and want to protect your edge without losing focus, you can apply anytime at https://www.tran.vc/apply-now-form/

Step One: Decide what is worth protecting

Start with your real advantage, not your feature list

Most robotics teams can list twenty features. That list is not your patent plan. Your patent plan starts with the single reason your robot works better, faster, safer, or cheaper than other options.

If you can explain that reason in plain words, you are already ahead. “We pick objects others can’t,” is not enough. “We pick objects others can’t because we detect slip early and adjust force in real time,” is closer to what you can protect.

Look for methods that survive messy real-world use

Robots fail in the real world for boring reasons: dust, glare, uneven floors, worn parts, weird object shapes, rushed operators, bad network, and shifting loads. If you solved these problems in a repeatable way, you likely built something valuable.

These solutions often look small, but they create big business outcomes. They reduce downtime, reduce damage, and reduce support burden. Those are the kinds of methods competitors want, because they turn a demo into a product.

Target the “system glue” that competitors copy after they see traction

In robotics, many teams share similar sensors and similar motors. The edge is often how your modules work together. The handoff between perception and planning, or between planning and control, is where performance is won.

Competitors can buy similar parts. They cannot easily copy your architecture choices unless you reveal them. This is why protecting the way your system connects and makes decisions can matter more than protecting a single component.

Protect the data loop if it makes performance improve over time

If your robot gets better through usage, you have a loop that creates compounding advantage. The loop may include what data you collect, how you label it, how you filter out bad runs, and how you safely push updates back to the fleet.

A competitor might try to build the same loop once they see your results. If your loop is special, it can be one of your best early patent targets, because it is closely tied to your long-term lead.

Step Two: Use staged filing to control costs

Why staged filing is the budget founder’s best friend

Many teams think they must wait until everything is perfect. That is how they end up filing late and paying more. A staged approach lets you lock your earliest date for an idea, then improve the filing as you learn more.

This approach also matches how robotics products actually get built. You start with a working method, then you refine it through tests and field runs. Your patent plan can follow that same pattern.

How a provisional filing helps you move fast

A provisional application can help you capture the core idea before you publish it in a demo, a pitch, or a pilot. It is not magic, but it can be a practical tool when your product is still changing.

The key is detail. A weak provisional that lacks steps, options, and examples can fail later when you try to convert it. The goal is not to file something thin. The goal is to file something clear that you can build on.

When to add a second filing instead of “fixing later”

Robotics teams evolve fast. Sometimes the method changes in a way that becomes a new invention. In that case, adding another filing can be cheaper and safer than trying to stretch the first one to cover everything.

If you wait and try to combine too many ideas into one late filing, you often lose clarity. That can increase cost and reduce strength. Filing in clean chunks can keep the work simpler and more defensible.

How to time filings around demos and public talks

Public sharing is where many robotics startups accidentally give away patent rights. Videos, conference slides, blog posts, and even a sales deck can count as disclosure if it contains key details.

A budget-safe habit is to treat every public reveal as a deadline. If you plan to share how something works, you should first capture it in an invention note and consider a filing. This keeps you from rushing in panic after the fact.

Step Three: Write invention notes that save you money

The one-page invention note that keeps your team aligned

A strong invention note is short but complete. It helps your attorney draft faster, and it helps your team remember what was actually new. Most important, it turns “tribal knowledge” into a record you can use again.

The note should explain the real problem, the failed attempts, and the method that finally worked. It should include the steps in order, because patents protect methods best when the steps are clear.

How to capture “the method” in a way that can be patented

Many engineers describe what the robot does, but not how it does it. To fix this, describe the decision points. What signals do you measure? What thresholds matter? What actions happen next? What happens if the signal is missing or noisy?

This makes your method readable to a non-expert and usable for patent drafting. It also forces you to separate the core from the optional pieces, which is helpful for both product and protection.

The easiest way to make your filing harder to copy

Competitors rarely copy your exact setup. They swap sensors, swap models, or move compute to a different place. That is why your invention note should include a few alternate versions that still follow the same idea.

You do not need a long list. You need thoughtful coverage. If the core method stays the same even when parts change, that is exactly what you want your patent to protect.

How to keep invention notes from becoming busywork

This should not feel like paperwork. The best time to write the note is right after you solve a hard issue, while the details are still in your head. It usually takes less time than a long internal message thread, and it reduces repeated explanations later.

If you build it into your routine, it becomes part of how you scale knowledge. That alone can be worth the effort even before you file anything.

Step Four: Choose claims that match how robotics gets copied

Why “outcome claims” fail and “step claims” win

A common mistake is to try to claim a result, like “better grasping.” Results are easy to say and easy to reject. Patent examiners want the steps that produce the result.

In robotics, those steps can be described clearly: sensing, estimating, deciding, acting, and verifying. When your filing follows that structure, it tends to be stronger and easier to defend.

How to protect the core without getting trapped by details

Founders sometimes fear that if they share too much in a patent, they are giving away secrets. In reality, you can protect the core method while still keeping certain tuning details as trade secrets.

The key is to define what must happen for the method to work, then describe multiple ways it can be implemented. This makes it harder to design around, while still leaving room to keep your best tuning private.

How to cover both hardware and software in one story

Robotics inventions often touch both hardware and software. A sensor placement choice may only matter because of the algorithm that reads it. A control loop may only work because of a certain mechanical feature.

A strong patent story connects these pieces. It explains the system in a way that shows the invention is not a random code snippet or a random bracket. It is a coordinated method that produces reliable behavior.